- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- Belle Vue – search archives catalogue

- Digital Resources

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Prints and Photographs

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Blog

- Support us

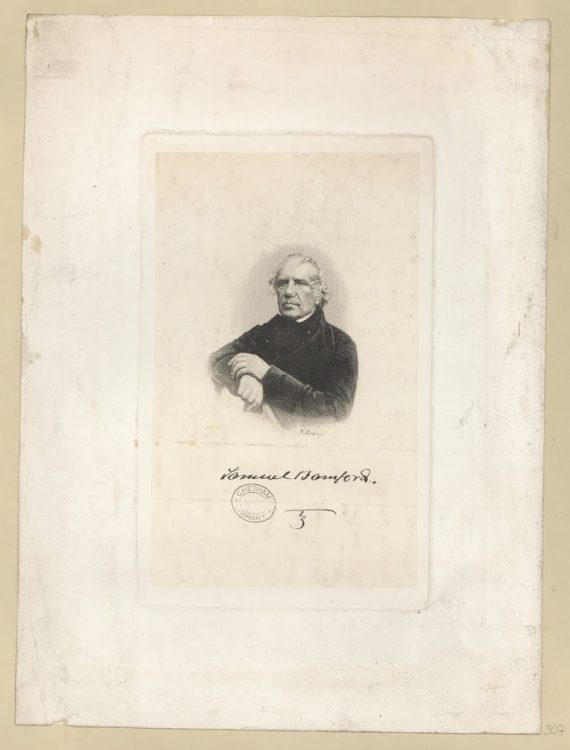

Samuel Bamford (1788-1872)

‘The more the bloody tyrants bind us

the more united they shall find us.’

The Manchester Scrapbook is a fascinating miscellany of drawings, pen and ink sketches, watercolours, maps, prints and engravings depicting Manchester places, buildings and people in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It was compiled by Francis Egerton, 1st Earl of Ellesmere, and presented to the Library in 1838. Many of the characters portrayed are rarely remembered, but others such as Samuel Bamford are still familiar, at least to readers interested in Manchester’s radical history. Finding Bamford’s portrait in the scrapbook led me to explore the library’s comprehensive collection of publications by and about Bamford. His writing is particularly valuable as accounts written by working people are remarkably absent from our history.

|

| Samuel Bamford – Manchester Scrapbook portrait |

Activism

Bamford, a silk weaver born in 1788, was a well known political activist immersed in the reform movements of the period. The library holds several editions of his two volume political autobiography, Passages in the Life of a Radical. The 3rd edition was printed by Bamford’s friend John Heywood, a local bookseller and printer.

|

| Cover – Passages in the life of a Radical |

Bamford’s first hand account of his life as an activist from 1816 to 1821 contains vivid, passionate writing from a witness who conveys the excitement and optimism and well as the disapointments and bitterness of his struggles, for instance his response to the suspension of Habeas Corpus which :

‘… seemed as if the sun of freedom were gone down and a rayless expanse of oppression had finally closed over us.’

Many aspects of Bamford account will be familiar to today’s activists: meetings, discussions, resolutions, writing, marching, arguments, splits, arrests and imprisonment, although fortunately we are no longer hung for high treason. Groups were also plagued by infiltrators and informers such as ‘Oliver the spy’ who reported on the activities of the Middleton Hampden Club, which Bamford set up in 1816 to campaign for parliamentary and social reform:

‘It was not until we became infested by spies, incendiaries, and their dupes – distracting, misleading, and betraying – that physical force was mentioned among us.’

Bamford was a man of strong opinions. On the 1 January 1817 the Hampden club passed resolutions calling for universal manhood suffrage and annual parliaments. Although he was committed to universal manhood suffrage, Bamford’s depiction of the ‘bungling knavery’ of the election process illustrates his objection to an annual repetition:

‘Behold the banners: hear the music; mere glare and noise; the speakers – one side yelled dumb, the other drummed deaf – good men bullied by ruffians, and spit upon by poltroons, – demagogues cheered – scurrility applauded – fraud devised and practised – truth suppressed – falsehood blazoned – friendship – severed hatred gratified – courage threatened – cowardice rewarded – vanity flattered – modesty disparaged – cupidity bribed – sobriety scoffed – gluttony indulged – conscience hushed – honour abandoned- wrong triumphant- right abashed and contemned.’

Bamford played a significant part in organising the Middleton contingent of the reform meeting in St Peter’s Fields, Manchester, that became the Peterloo Massacre. His eyewitness account of the day, in Passages in the Life of a Radical, depicts the horror of the cavalry charge on the crowd:

‘The cavalry were in confusion : they evidently could not, with all the weight of man and horse, penetrate that compact mass of human beings ; and their sabres were plied to hew a way through naked held – up hands and defenceless heads ; and then chopped limbs, and wound – gaping skills were seen ; and groans and cries were mingled with the din of that horrid confusion. Then, “Break ! Break! They are killing them in front and they cannot get away ;” and there was a general cry of “Break! Break.” For a moment the crowd held back as in a pause ; then was a rush, heavy and resistless as a headlong sea; and a sound like low thunder, with screams, prayers, and imprecations from the crowd-moiled, and sabre-doomed, who could not escape.’

Social comment

Bamford was imprisoned in Lincoln Castle jail for his part in Peterloo. After his release, his political activity became less central to his life. He returned to work as a silk loom weaver but found it hard to make a living and started to focus on writing to supplement his income. In addition to his autobiographical writing, he was Manchester correspondent for the London based Morning Herald and wrote material about Middleton for the Manchester Guardian.

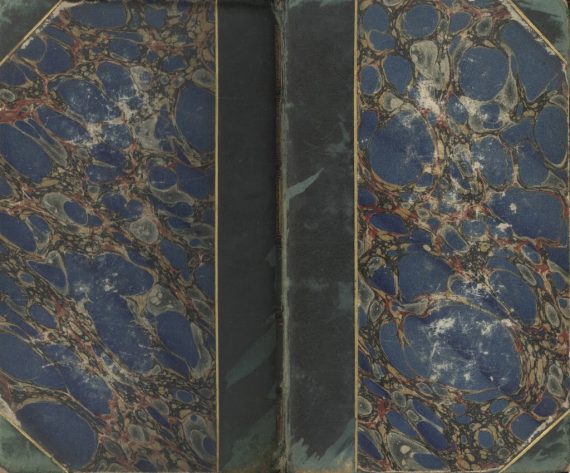

The library has recently acquired a rare first edition of Walks in South Lancashire and on its Borders which Bamford published in 1844. Marbling and gilt lettering on the cover make this a lovely volume. In this publication he portrays the lives and social and industrial conditions of Lancashire working people through a series of chapters and sketches with headings such as ‘An Insane Genius’, ‘The Traveller’, ‘A Temperance Orator’, ‘Robert, the Waiter’, ‘Walks amongst the Workers’ and ‘What should be Done’?

|

| Cover – Walks in South Lancashire |

Dialect

Bamford was interested in dialect even though he wrote most of his work in standard English. He used the vernacular when reporting working men’s dialogue in Passages in the life of a Radical and wrote a small number of dialect poems such ‘Tim Bobbin’ Grave’, published in Hours in the Bowers.

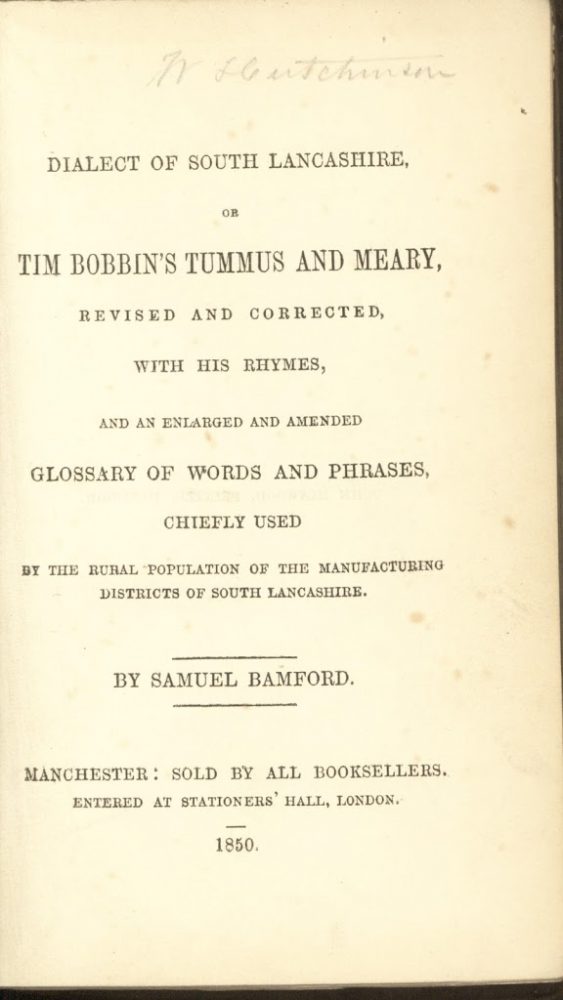

The library holds an 1850 edition of Bamford’s Dialect of South Lancashire published by Heywood who was also a dialect writer. John Collier, who was also known as Tim Bobbin, wrote the original volume but Bamford thought it represented Cheshire rather than Lancashire dialect so published his own ‘correct’ version.

|

| Dialect of South Lancashire title page |

|

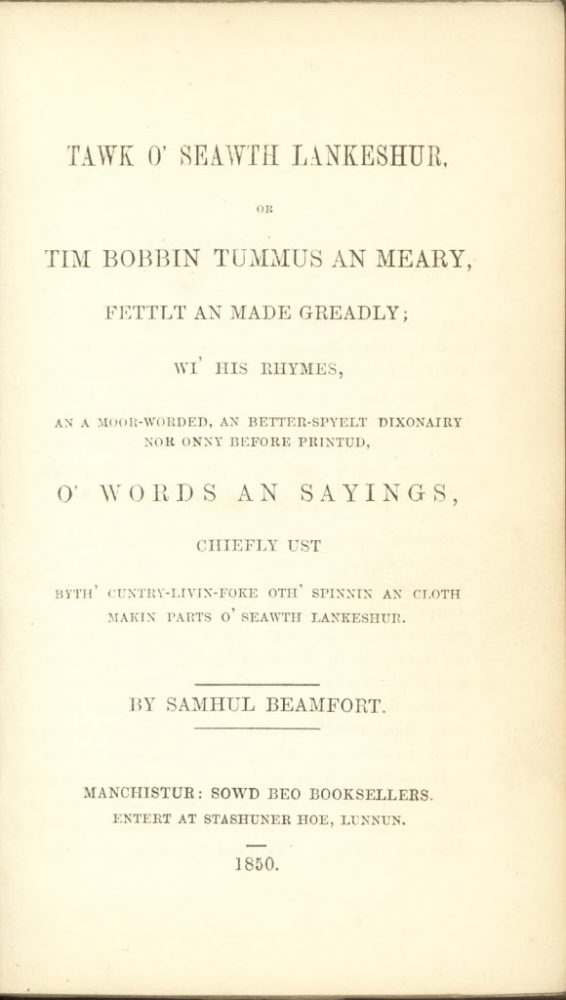

| Vernacular title page |

This text takes the form of a dialect conversation between Tummus and Meary (Thomas and Mary) in which Tummus tells about his misfortunes on a journey to Rochdale. The piece is a fascinating illustration of how words become obsolete as language evolves over time. The glossary of words and phrases at the back is essential the modern reader confronted with passages such as:

‘Zeans! O’ Inglanshoyr’ll think at yoar glenting at toose fratching, byzen, cradinly tykes, at writ’n sitch papers osth’ Test : an sitch cawf-teles as Cornish Peter, at fund a new ward, snying weh glums an gawries.’

‘Inglun-shoyer all England, Glentin glancing, Toose those, Byzen blind.’

We don’t find Fratching’ in the glossary, perhaps it was in common use at the time and readers didn’t need to be told that it means quarreling.

Poetry

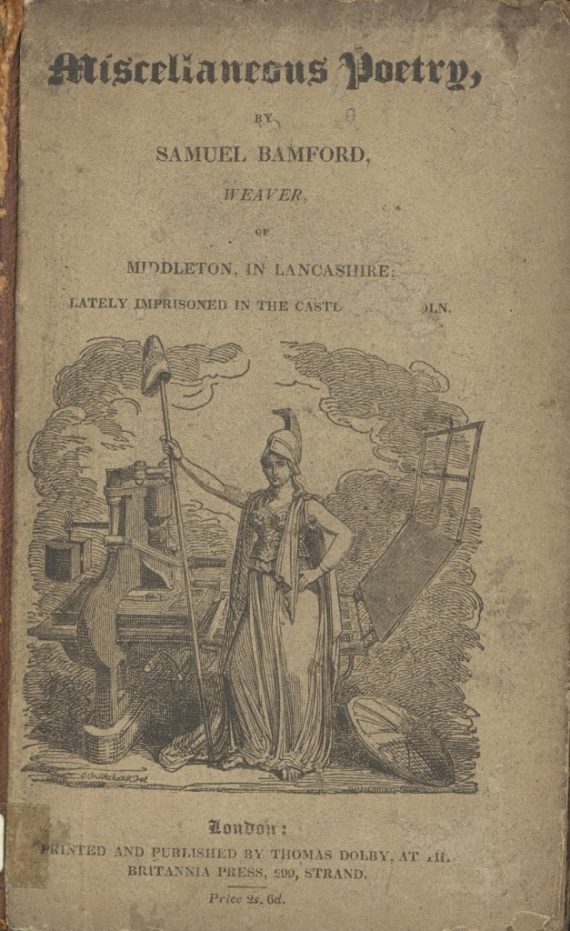

The Library holds several volumes of Bamford’s poetry including Hours in the Bowers, 1834 and Poems, which he self published in 1843. Miscellaneous Poetry was published in 1821 by Thomas Dolby at Brittania Press, The Strand, price 2s. 6d. A clue to the intended reader is seen in the description of the author as ‘Samuel Bamford Weaver of Middleton in Lancashire, lately imprisoned in the Castle of Lincoln’ as well as in the cover illustration by George Cruikshank, a prolific and popular caricaturist and satirical politic artist.

|

| Miscellaneous Poetry front cover |

There is an extraordinary warning in the preface:

‘In laying before the public the poems of SAMUEL BAMFORD , the Publisher is totally unmindful of the swift and bitter arrows of Criticism. His Author is unlettered. The arrows of Criticism which to Book Poets convey bitterness and and dismay , fall pointless and powerless against SAMUEL BAMFORD. He lives not in books. He sings to the motion of his loom…’

Bamford’s poetry is very variable. His prison writings include Eclogue, written when he was incarcerated in Coldbath-Fields prison awaiting trial for High Treason in 1817 and Hymn to Hope written in Lincoln Castle. He wrote lyrical as well as political works, addressing themes of life, love, nature and death.

Bamford wrote for the rest of his life. In 1858 on his 70th birthday started a diary which has been edited by Martin Hewitt and Robert Poole and published as The Diaries of Samuel Bamford. The diaries offer invaluable insights into the activities, contacts and reflections of a long lived working class man:

‘Above all, they reveal the poignant struggle for dignity of an old radical fallen on hard times and determined to set the historical record straight.’

Look in the library catalogue for publications by and about Bamford : http://www.chethams.org.uk/catalogue

4 Comments

colin unwin

I finally found Samuels grave in St Leonards church grave yard… a month ago 8-7-2019,,,,you couldn,t see the inscription …so I went home and got some cleaning stuff and went back and cleaned his headstone…..I also made a sign directing people who want to find his grave …

ferguswilde

Hi Colin, thanks for the comment – I’m sure those moved by the recent Peterloo interest will thank you too.

PAUL REED

The Manchester radicals are once again becoming very much back in vogue ‘ as this is the month and year of the Manchester Peterloo Massacres (16 th August 1819) . His writing’s are similar to those of the Failsworth, born Lancashire, writer Ben Brierley, who also wrote in Lancashire dialect . Although’ by all accounts BAMFORD’s life was hardened by his poverty. Nevertheless , his writing’s are wonderful and one wants more and more. The BBC or other media outlets should dramatize his autobiography; which would be marvellous viewing for our young folk.

ferguswilde

Hi Paul, thanks for the comment – Bamford’s an interesting character indeed. The feature film Peterloo, released recently, does draw on his writing and features him as a major character. There might well be scope for another drama, though maybe a documentary would work better for his life story?