- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

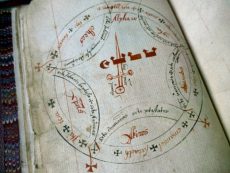

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

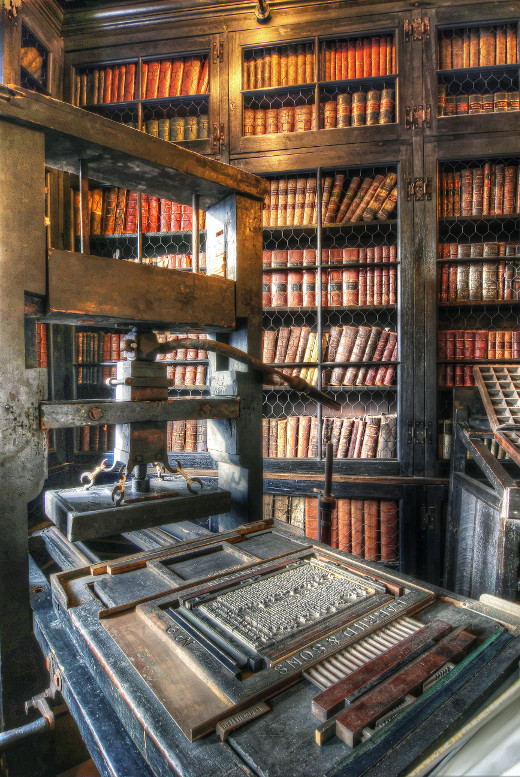

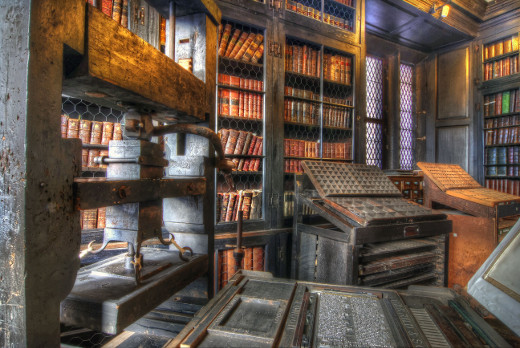

Wooden Printing Press

The wooden hand printing press now standing in Chetham’s Library is believed to date in part from the early seventeenth century. It was donated to the Library in 1900 by George Falkner and Sons, printers of Deansgate, Manchester, along with some additional equipment including a type-casting mould, printing ink balls, a typecase and compositor’s stick.

The press at Chetham’s was long believed to be composed of mostly original seventeenth-century work. When expert Alan May dismantled the press, however, he became convinced that while the metalwork and essential core elements of the press were indeed ancient, the woodwork had been substantially replaced in the nineteenth century by a craftsman more familiar with roof construction than printing press construction. Fewer than seventy wooden hand presses such as this one (also known as common presses) survive globally, and there are no surviving examples of presses produced before the seventeenth century.

The common press is operated by a heavy iron screw held in a wooden frame. It was first developed in the fifteenth century and continued with only slight variations until the nineteenth century when wooden presses were gradually replaced by metal ones. The Chetham’s press is of special interest to the Library since all the books housed in the part of the library where the press and equipment are displayed were made on wooden hand presses of similar construction. It is believed to have been in actual use in Manchester until the nineteenth century.

The wooden press works very simply. A heavy bar is used to exert pressure on two flat plates, one containing inked type, the other a prepared sheet of paper. When the pressure is released, an impression is gained. It is heavy work, and on a press like this, two pressmen working together would be able to print around 250 pages per hour. The printed pages would then be hung up to dry, ordered, and tied in bundles. On each page of a book the printer would have hidden a small letter or number known as a signature mark, which the book binder would use to fold, cut and assemble the pages in the correct order. Quite often the book would not be bound until it had been sold, with the new owner specifying how it was to look – the more money changed hands, the more elaborate was the finished product.