- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Collections

Chetham’s Library is open to readers Monday to Friday 9am-12.30pm and 13.30-16.30pm by prior appointment. Please contact us to arrange a study visit.

Manuscripts

From illuminated manuscripts made for royalty to the minutiae of personal life – diaries, letters, account books – the Library has a wealth of special items and collections. Chetham’s holds over forty medieval manuscripts, including the thirteenth-century Flores Historiarum of Matthew Paris – a chronicle of world and English history; a fifteenth-century Aulus Gellius, bound for Matthias Corvinus, King of Hungary; and an important compendium of Middle English poetry. Among the modern manuscripts are Horace Walpole’s account of money spent on his house at Strawberry Hill, and a seventeenth-century prose and verse miscellany containing letters by Ralegh and Bacon, and poems by Donne and Jonson. There are four works by the poet Robert Southey, notably his Letters of Espriella, in which he offered his view of Manchester: ‘a place more destitute of all interest it is impossible to conceive’.

The manuscript and archival collections are mainly concerned with the history of the north west of England. There are extensive collections of title deeds, institutional records and antiquarian papers collected and compiled by local historians. Chetham’s has the oldest history of Manchester: Richard Hollingworth’s 1656 autograph of Mancuniensis, and the first ever census of Manchester, compiled in 1773–74.

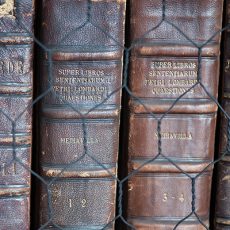

Printed books

There are well over 120,000 printed items, of which over half were published before 1850. Most of the Library’s earliest acquisitions were bought second-hand and many of these have an interesting provenance. Ben Jonson’s copy of Plato for example, was bought in 1655 for the sum of £3 10s. A 1539 copy of Prosper of Aquitaine, which was bound in white deerskin for Henry VIII, was bought in 1674 for only eight shillings. Although these rare volumes, ironically, were acquired relatively cheaply, printed books were extremely valuable commodities. The Library was prepared to spend vast sums of money on particularly desirable volumes, paying as much as £20, for example, for an eight-volume Bible. By comparison, the first Chetham’s Librarian was paid £10, plus board and lodging, for a year’s work.

The first book acquired by the Library, a set of the works of St Augustine for which the Library paid the sum of £7, set the standard for a very large and particularly fine collection of theology. There is a good collection of Bibles, with all four of the great Polyglots represented, as well as Erasmus’s New Testament in the original Greek. There are extensive holdings of patristic and reformation theology, church history and liturgy. The Library also has a first edition of Cranmer’s Booke of Common Prayer (1549), the first single manual of worship in a vernacular language.

Of the secular history books perhaps the most important is a copy of Hartmann Schedel’s magnificent Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493, complete with a sixteenth-century translation into English in the margin – the only time this work has ever been translated. English history includes all of the major town and county histories, and a large collection of books on heraldry and genealogy. There are extensive holdings of topography and maps, of which Christopher Saxton’s atlas of 1579, the first printed atlas of England and Wales, is the best known.

The Library’s scientific collections are even more impressive: Aristotle, Euclid, Galileo, Copernicus and Kepler were all acquired at the outset, as were outstanding works of natural history and medicine, notably early editions of Galen and Hippocrates. The Library also showed an interest in the new science, and bought first editions of Robert Hooke’s Micrographia (1665) and Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica (1687). The literature collection contains virtually all of the Greek and Latin classics, including the first printing of Homer (1488) and Plutarch’s Lives (1517), as well as editions published by many of the great printing houses of Europe – Jenson, Aldus, Estienne, Plantin and Elsevir. English literature is strong in drama and poetry, with many first editions of key works such as Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language (1755) and Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667).

The scholarly collection of books begun by Humphrey Chetham’s governors in the seventeenth century is only a part of the Library’s holdings. By the mid-eighteenth century the Library began to acquire large illustrated works and multi-volume periodicals and journals, and a century later the emphasis shifted again. Until the nineteenth century Chetham’s had been the only repository for books and printed matter in Manchester, but with the creation of rate-supported public libraries, the governors agreed that the policy of buying books on all subjects could no longer be sustained. Instead the decision was made to specialise in the history and topography of the north west of England. Chetham’s now has one of the largest collections of material relating to Manchester and its region, with extensive holdings of prints, maps and photographic slides, and large runs of newspapers, trade directories and periodicals.

Documents of everyday life

As well as printed books and manuscripts Chetham’s has an enormous amount of ephemera, with particularly rich collections of bookplates, postcards, chapbooks, broadsides, ballads, theatre programmes, posters, trade cards and bill heads. Many of these were given to the Library in 1852 by the Shakespearean scholar, James Orchard Halliwell-Phillipps. His collection of over 3,100 items contains many unique works: fragments of medieval manuscripts, sixteenth-century black-letter ballads, political, social and commercial broadsides, and songs and music dating from 1680 to 1750.

There are many albums and scrapbooks of local material, including rare specimens of Manchester printing. One album, for example, known as the ‘Cambrics Scrapbook’, contains over 250 broadsheets, ranging from light-hearted entertainment handbills to notices of serious political issues, mostly dating from the end of the eighteenth century. Another work, the ‘Manchester Scrapbook’, was compiled by the Earl of Ellesmere and was given to the Library in 1838. This large work contains almost 400 items, including pen-and-ink sketches of local characters, scenes and customs.