- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

The Flowers of Histories

A Universal History from England's most influential chronicler

The great royal Benedictine abbeys of medieval England were some of the most important centres of historical writing in the country. Of these, St Albans had the most continuous and perhaps the most influential tradition, producing important narrative history in almost every generation. It produced two long pieces known as Flores Historiarum, the ‘Flowers of Histories’, the first compiled by Roger of Wendover, covering the period to 1235.

St Albans Monk Matthew Paris in a self portait (London, BL MS 14.C.VII, Fol. 6r)

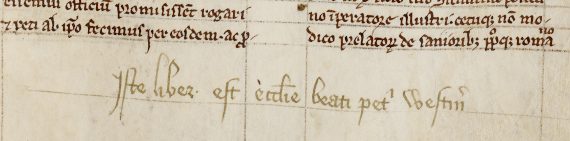

The second was compiled and in part composed and written out by the celebrated Matthew Paris (ca. 1200-1259), a prolific author of histories and sacred texts who met kings and princes, and was close to the events of his own time by virtue of the major abbeys being among the few places that could accommodate the royal court for its meetings and visits over festivals such as Easter and Christmas. The manuscript was created with the aim of presenting it to the sister abbey of Westminster, where the Benedictine congregation and King Henry III (1216-1272) were building the current Abbey as the resting place of St Edward the Confessor. The Westminster monks were keen to add their ownership marks once it had arrived:

‘This book belongs to the church of Blessed Peter, Westminster’ – one of many ownership marks added at the Abbey

The compilation of the Matthew Paris Flores Historiarum was begun in the mid-thirteenth century. Its narrative begins with the creation of the world, and concludes with the events of 1326. This wonderful manuscript was the Library’s first major donation and, indeed, first manuscript accession, arriving within the first couple of years of the Library’s existence in 1657. It was given to the Library by Nicholas Higginbottom of Stockport, and an added ‘title page’ in manuscript provides all we know about this gift. We do not have any information about Mr Higginbottom, his connection with Chetham’s Library or how he came to possess such an important relic of the medieval world, but we are grateful he chose our library as the most suitable place of deposit.

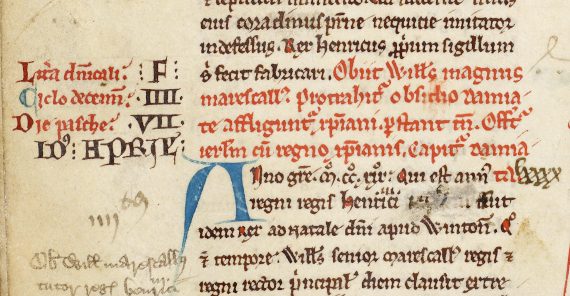

Record of the death of William the Marshal, the old soldier who protected Henry III in infancy and childhood

Coronation scenes

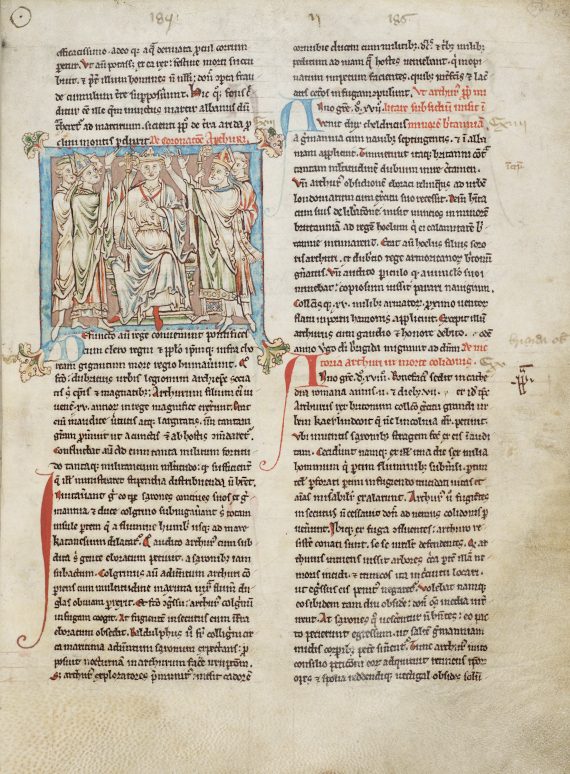

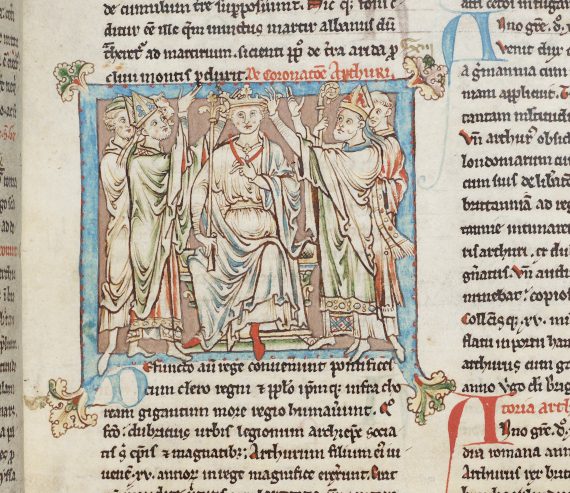

Although not the most lavishly illustrated manuscript in the Library’s collection, the ten pen-and-wash illustrations in the Flores are famous and are often reproduced in print. We can’t wait to see the facsimile in all its glory but for now we can have a look a some of the highlights of this truly remarkable manuscript. We’ll be adding more to this page week by week. The most frequently reproduced elements of the manuscript are stylised coronation scenes. Like the text, they are by several different hands, although all but one share artistic features that link them to the St Albans scriptorium. Here is the leaf with the first of the scenes in its context with the text.

Illustration in context in the two-column text

We now regard King Arthur as a legendary figure, with perhaps some more-or-less truly historical person somewhere behind the legend; or some regard him as a complete myth with no real antecedents. ‘He’ – if there really was a he – is nonetheless still the inspiration for numerous books, films and television dramas, many of which draw on the courtly literature tradition with Arthur as the constant background figure to a series of adventures happening to his younger knights. This tradition was mostly expressed first in verse and in dialects of French. But for the Flores Historiarum there is a strictly historical, real Arthur, backed by a Latin language prose history tradition we can trace back to the twelfth-century historical writer Geoffrey of Monmouth. Here is the scene in closer detail. As we add more of the coronation scenes, you will see the stylised nature of the depiction, and how it is designed to fit the text layout on the parchment.

‘On the coronation of Arthur’ – as real and solid as the succeeding coronations in this book

A Universal History

As modern readers we expect a piece of historical writing to deal with a particular topic, perhaps a time, area, or socio-economic phenomenon. We would not generally expect to find a book on the Russian Revolution starting with an account of the creation of the physical universe. This is because we are not medieval monks. Even a work such as the Flores Historiarum, which historians now turn to for detailed and often critically sophisticated accounts of the writers’ own times, accepted a duty to take its readers from the very beginning of the world, its creation by God, to the present. After the manuscript went from St Albans to Westminster Abbey (via Evesham as recent scholarship confirms), continuators such as Robert of Reading carried on the narrative and added their leaves to the manuscript. The latest portion of the work is much used by historians of the reigns of Edward I and Edward II.

There’s more to this than merely ‘let’s begin at the beginning’; in modern times we generally prize originality and individuality in a writer. For medieval writers this is pretty much inverted. What they prized was authority – precedent with pedigree – and ‘God’s truth’. It’s no coincidence that ‘author’ and ‘authority’ come to our language via ‘auctor’ and ‘auctoritas’. The world and what happens in it is a playing out of divine purpose, and human action is about the moral worth of a deed done or left undone by the players on this stage. Can the world and the individuals in it see God’s purpose? Will they act accordingly? Will the fallen nature of sinful mankind triumph in evil? Behind all the judgements in the narrative of a universal history, which in detail may be very practical and political in dealing with specific incidents, lies this broad question.

Why this history?

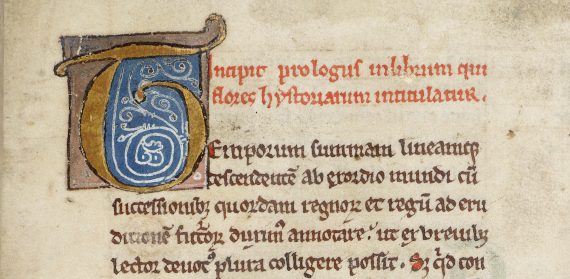

The fact is that monastic historians tend not to make their editorial policy, or even their names, explicit. In the medieval mind, ancient authorities always had the better claim to recognition than did the monastic historian of the day, and novelty was something that had to be excused and backed by something with the weight of time behind it. But the compilers of the Flores do answer the question, ‘what is this book for?’ The manuscript as we have it today starts with a handwritten ‘title page’ supplied probably at the time it was given to Chetham’s in the 1650s. A partially completed calendar of the year with saints’ days and feasts, a very usual inclusion in any monastic book, follows. The text proper begins with this:

If we want to know the basics about a modern book, we look at the title page. It’s usually going to tell us the title, the author, the name of the publisher, often the city they’re in, and the date. Medieval manuscripts (and printed books until the beginning of the 16th century) don’t do this. They usually have an incipit ‘it begins’ and an explicit ‘it finishes’. Very often it’s the explicit that gives us any idea of authorship and date. The story with authorship and dating of Flores is more complex than this, but the incipit produces a prologue that is very clear about the reasons for writing:

We have brought into writing the main substance and line of the times coming down from the origin of the world, with the succession of certain kingdoms and kings for the erudition of those in the future, so that out of brevity the attentive reader can gather many things. […] They will find that the good life and customs of those who went before will be put forward for the imitation of those who come after, but the example of the bad will be described so that it may not be imitated but rather avoided.

The text of Flores fills three large volumes in the printed edition that’s most used nowadays, so brevity is not the word we might first think of. It’s all relative though; the text in large part represents a ‘Readers’ Digest’ reduction of Matthew Paris’ magnum opus, his ‘Greater Chronicle’, Chronica Majora. The printed edition of that work is in nine even fatter volumes, so Flores is indeed slimline by comparison!

The introduction turns then to give a foretaste of the moral examples the text will give. Signs and portents that create famine, death or other heavenly vengeance will be recorded as scourges for the faithful from which sinners will learn to run and perform penance if they see similar signs in the present. Examples from humanity’s early history will include: Moses the lawgiver; the innocence of Abel and guilt of Cain; the simplicity of Job; the lies of Esau; the malice of the eleven sons of Israel, and the goodness of the twelfth, Joseph.

The question of what writing history is actually for is still very much in debate. But to Matthew Paris, there is a clear answer: history is a mirror in which to look and judge our own and our contemporaries’ actions and lives. The standard of judgement is the only one available, that of God; but interpreting his will and judgements will not be easy!

Please call back, we’ll add more to this page to continue the exploration.

You can read a little more more about this magnificent treasure here: https://library.chethams.com/collections/101-treasures-of-chethams/flores-historiarum/