- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

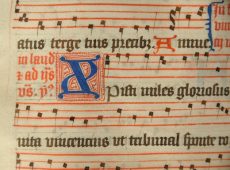

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

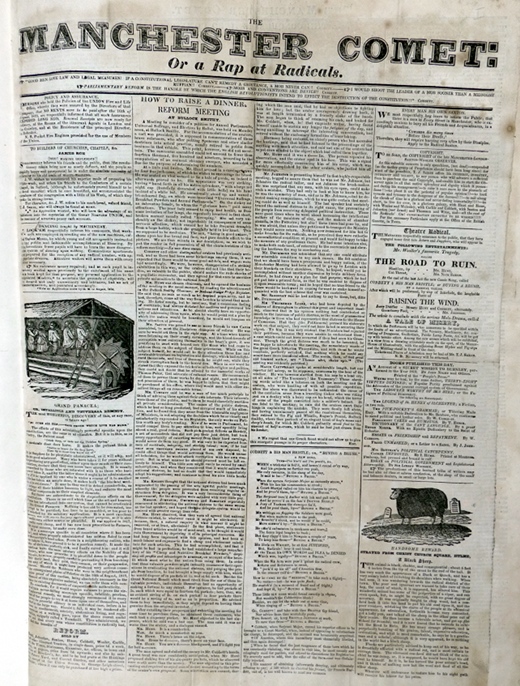

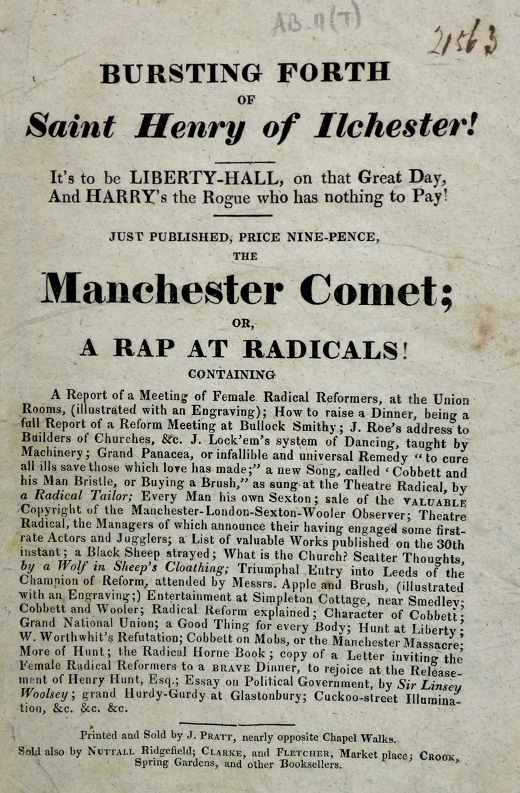

The Manchester Comet

1822

The Manchester Comet appears at first glance to be the first issue of a four-page newspaper, complete with a prospectus advertising its sale. In fact, it is nothing of the sort. The Manchester Comet or a Rap at Radicals is a piece of satirical publishing attacking radical politics, complete with spurious advertisements, in the form of a newspaper.

The Comet, which was published by Joseph Pratt, printer of Chapel Walks in Manchester, is surprisingly sophisticated for a piece of Tory propaganda. If the devil can be said to have all the best tunes, the radicals, rather than the Tories, generally have all the best satire – no surprise really, as they tend to attract the best writers and illustrators. Unfortunately, many of the polemics from both sides of the political arguments of the first decades of the nineteenth century are about as funny as an old Punch cartoon – with the obvious exception of Cruikshank – but the conservatives tended to produce at best feeble pastiches of radical works. William Hone’s radical publication The political house that Jack built, with thirteen cuts by Cruikshank, produced a series of dismal conservative parodies – The Dorchester guide; or, a house that Jack built, The radical-house which Jack would build, The real or constitutional house that Jack built, to name only three.

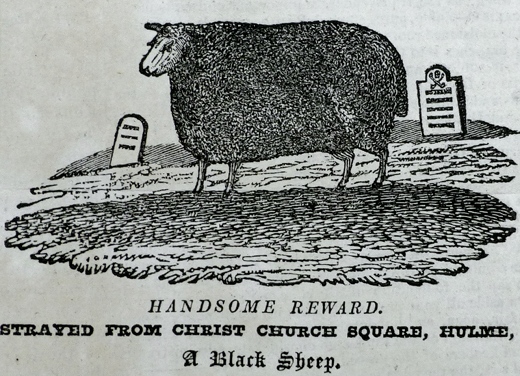

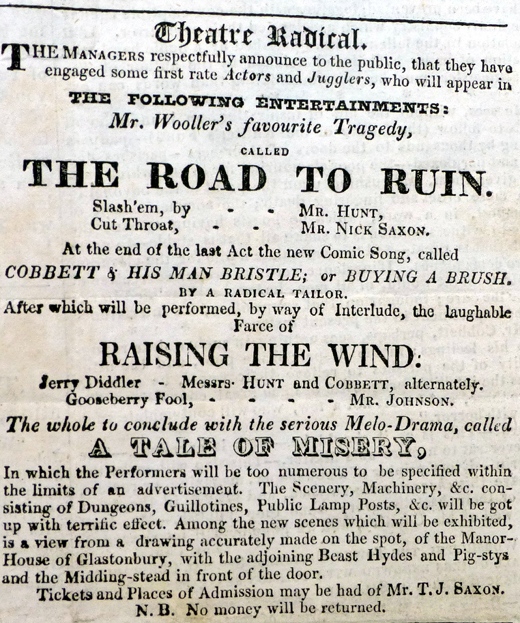

The Comet however, though not full of belly laughs, is both innovative and well produced, with particularly amusing advertisements, for example, the treadmills ‘by which young and old are speedily instructed in the polite and fashionable accomplishment of Dancing’ , the advertisement for the tragedy at the ‘Theatre Radical’ entitled ‘The Road to Ruin’ and a farce ‘ Raising the Wind’, as well as a reward for a black sheep strayed from Christ Church Square Hulme.

The illustrations are certainly admirable and the main picture – the large sketch of the meeting of the Female Radical Reformers of Manchester, which occupies a large part of the third page – is a remarkable work for at least two reasons. Firstly, although it is intended to be satirical rather than descriptive, it remains the only surviving illustration of this particular group. Secondly, the attempt to undermine female reformers by depicting them as drinking, dancing on tables or canoodling reveals that women were taken seriously, possibly for the first time, as a political force. They were ridiculed because they were important. Manchester was not alone in establishing a female reform society and women were seen as useful not simply because they could make banners and caps of liberty, but because they were able to to educate their children in the principles of reform. By 1819 the female reformers of Manchester were under the control of Mary Fildes, chairwoman of the Manchester Female Reform Society, and Susannah Saxton, secretary of the Manchester Female Reform Union, and Fildes and Saxon feature prominently in the ‘report’ of the meeting.

The illustration is full of rich detail, for example the man beneath the table, either sketching events or acting as a spy and reporting on the meeting, and the sack of ‘breakfast powder’ – a concoction based on roasted corn which was sold as a substitute for tea and coffee and which was recommended to Radicals as a means of boycotting taxed goods.

The Manchester Comet is at best a curio, a piece of ephemera. But it is in all probability unique. No other copy has yet surfaced in any other library.