- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

‘The Peaceful, the Pure, the Victorious Pen!’: The Sun Inn Group

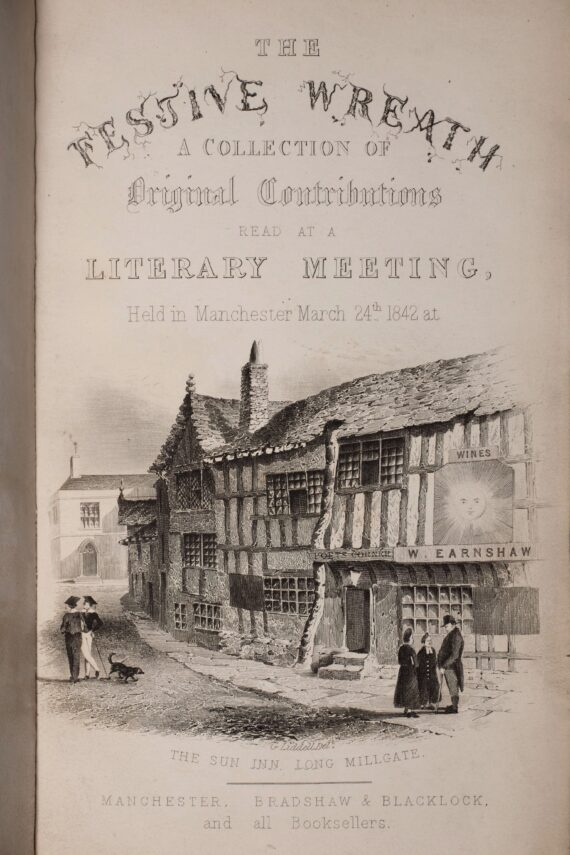

During the nineteenth century, Manchester was one of the most written-about cities globally; it was famously the subject of Percy Shelley’s ‘The Mask of Anarchy’, written following the Peterloo Massacre in 1819, and was later studied in Friedrich Engels’ The Conditions of the Working Class in England (1845) following weeks spent studying at Chetham’s Library with Karl Marx that summer. None of these writers were native to Manchester, however; although there were a few famed nineteenth-century Mancunian writers in the nineteenth century—chiefly Elizabeth Gaskell—many of them went overlooked or otherwise achieved little fame. Our current exhibition therefore shines a light on a collective of such overlooked writers, known as the Sun Inn Group. This group of largely working-class poets took their name from the Sun Inn, a timber-framed building that stood opposite the entrance to Chetham’s Library on Long Millgate where they met to recite poetry together in the 1840s. In turn, this public house earned the affectionate title of ‘Poet’s Corner’ from the literary gatherings that took place there.

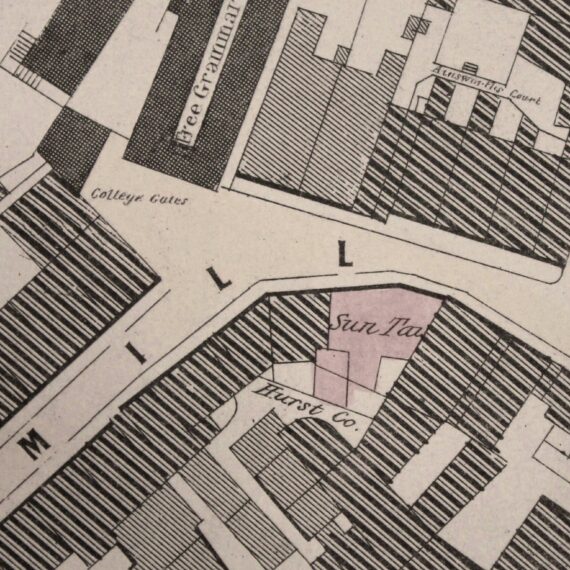

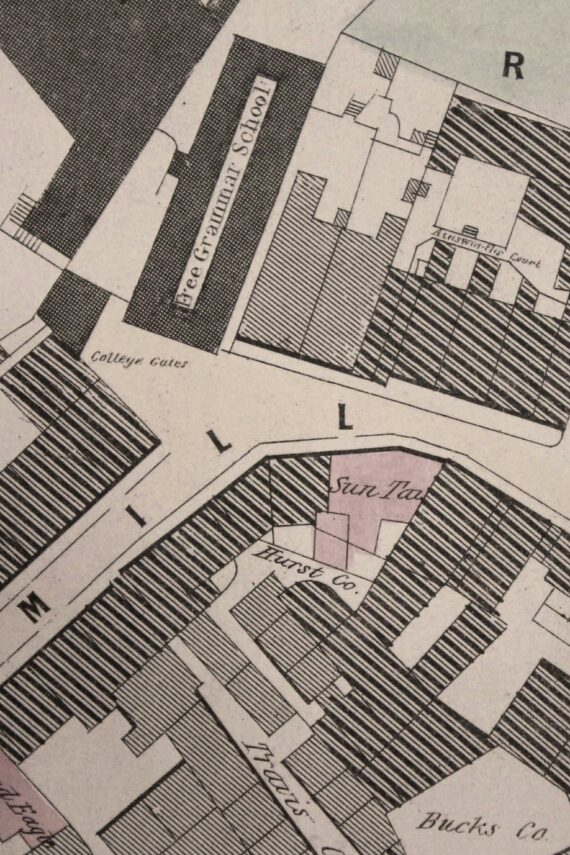

Figure 1: Joseph Adshead’s map of Manchester in 1851, showing the Sun Inn opposite the entrance to Chetham’s Library on Long Millgate (Chetham’s Library, Gal.M.2.1).

Although the Sun Inn Group was relatively short-lived, it did manage to achieve relative local fame, with The Manchester Guardian occasionally reporting on their meetings. One meeting was reportedly attended by roughly thirty people, who gave a series of speeches, poetic recitals and songs, and was—according to the Guardian—‘conducted with much harmony and kind feeling’. Amongst the attendees was John Bolton Rogerson, who, in addition to being a poet, acted as the group’s most significant organisational figure, arranging many of their meetings, acting as the chairperson or vice-chairperson during them, and later ensuring that members of the group received paid poetry commissions during his time as an editor for the Oddfellows’ Magazine. Rogerson was also responsible for compiling and editing the group’s only published anthology, The Festive Wreath, which was comprised of poems read at a meeting held in March 1842. According to the Guardian, this meeting was attended by over forty individuals.

Figure 2: John Bolton Rogerson (ed.), The Festive Wreath (Manchester: Bradshaw & Blacklock, 1842) (Chetham’s Library, 8.J.5.70).

Our collections include a copy of The Festive Wreath, which is currently on display as part of our exhibition. Much of this anthology—including a preface written by Rogerson—appears keen to assure readers of the group’s poetic capabilities and legitimacy, often listing the poets’ other accomplishments after their names. The collection also stresses the importance of the Sun Inn Group’s gathering together to combine their abilities for a greater purpose. The collection’s first poem, ‘The Poet’s Welcome’, was penned by the group’s leading light John Critchley Prince. In the poem, he welcomed both the poets and spectators in attendance at the meeting, and emphasised the significance of the gathering, declaring:

‘The scattered sons of humanizing song,

Like twilight starts ought not to reign apart

As jealous of each other’s light, but come

Clustering in one most glorious galaxy

Of mental splendour – as I see you now.

Although the poem feels overzealous in promoting the supposedly-divine nature of poetry, Prince’s love of poetry was lifelong. In the sixth edition of his own anthology, Hours with the Muses (1857)—a copy of which can also be found in our collections—he wrote that ‘poetry has been the star of my adoration, affording me a serene and steady light through the darkest portion of my existence.’ Prince’s journey towards becoming a poet was a difficult one; his father, a reed-maker, resented his son’s interest in literature, and the family’s financial struggles made accessing literature a difficult endeavour. Prince nevertheless stressed that ‘poverty, want, and punishment were unable to exterminate’ his passion for poetry. In a working men’s journal, Prince reminisced about how he had stolen away from his labour, into a ‘mental feast from the pages of a Pope, a Prior, a Gay, and more especially a Goldsmith’, a medley of older poets on whom Prince’s own poetry later drew. As his list indicates, Prince’s poetry is more evocative of older poets such as Milton, Spenser, and Shakespeare, all of whom were more accessible to those with little money than the contemporary Romantics, whose works were more expensive and took some time to become available in the north.

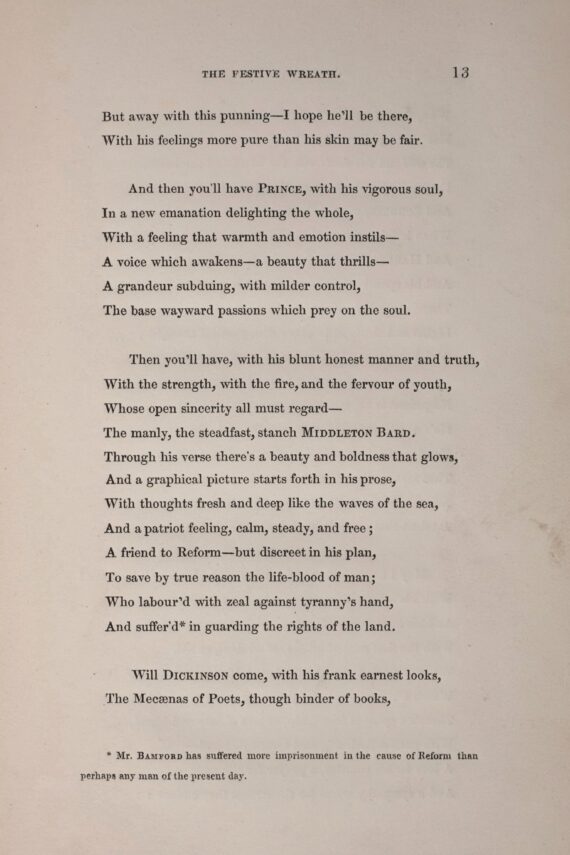

A similar sentiment is echoed later in The Festive Wreath, in Alexander Wilson’s self-referential poem ‘The Poet’s Corner’, an upbeat drinking song that implicitly attributes the success of the Sun Inn Group to ‘Tragedy, Comedy, Byron and Burns; / To Milton and Moore’. This poem is also the second of two within the anthology that explicitly names many of its members (the first being George Richardson’s poem ‘A Poetical Replication’). These poems are incredibly helpful when it comes to identifying the Sun Inn Group’s most prominent participants, and work to paint a colourful picture of the contemporary Mancunian literary landscape. Both poems are keen to portray their group as being comprised of a range of different members, each with their own poetic styles: Richardson turns from Samuel Bamford’s prosaic ‘graphical picture[s]’ to John Scholes’ medievalist ‘legend of Naworth’s old tower’.

Figure 3: George Richardson’s ‘A Poetical Replication’, in John Bolton Rogerson (ed.), The Festive Wreath (Manchester: Bradshaw & Blacklock, 1842) (Chetham’s Library, 8.J.5.70, p. 13).

Alongside their members’ various poetic inclinations, both Wilson and Richardson emphasised the group’s diversity of character and origin; Wilson playfully characterised the group as consisting of ‘publicans, sinners, Cork Cutters [a reference to James Boyle] and dinners’, and suggested a variety of political beliefs, writing of ‘whig agitators, and tory debaters’. Indeed, politics do not appear to have been a particularly taboo subject, although the group rarely used their poetry for the purpose of political activism. Richardson’s reference to Bamford eagerly underlines Bamford’s radical political beliefs and activism, and mentions the many times that he had had been arrested and imprisoned: a footnote jovially informed readers that ‘Mr. Bamford has suffered more imprisonment in the cause of Reform than perhaps any man of the present day’.

Despite their range, however, these poems do not capture the full picture. The Sun Inn Group was home to a number of female poets, including Isabella Varley (née Banks), Eliza Craven Green and Eliza Battye, all of whom had poems featured within The Festive Wreath. None of these members were present at the festival: the Guardian noted that a number of the group’s female members did not attend, but did have some of their poems read during the event. Isabella Varley was an elusive member of the group who once hid behind a pair of curtains to hear her poem recited during a meeting. If one were to use ‘The Poets’ Corner’ and ‘A Poetical Replication’ as a basis for the group’s members, however, it would seem like there were no female members within the Sun Inn Group at all. Similarly, Richardson and Wilson’s poems seemingly refer to Robert Rose, ‘the bard of colour’, out of obligation alone; Richardson made no mention of Rose’s poetic capabilities, and merely requested that Rose attend the meeting ‘with his feelings more pure than his skin may be fair’, while Wilson wrote that Rose’s prose had poetry flow from it (as if to suggest that Rose was otherwise incapable of the delicate art of poetry).

The rest of The Festive Wreath consists of less self-referential poetry, featuring lyric pieces, ballads, sonnets, and various other pieces of conventional poetry. Perhaps the most striking element of this collection is the continued thread of domesticity and the commonplace. Craven Green’s poem, ‘Children Sleeping’, devotes itself to the domestic sweetness of witnessing one’s kin asleep, while John Ball’s poem, ‘To My Daughter’ is ‘affectionately dedicated’ to his wife, and takes joy simply in the sound of his two year-old daughter’s attempts at lisping her parents’ names. As was previously mentioned, the group lacked a particularly political edge to their poetry, but there is nevertheless a sense of something radical in their emphasis on domestic matters, respite and personal relationships. Elijah Riding’s simply-named ‘Stanzas’ is a patriotic piece, which sees him celebrate love for one’s country through the mere act of spending time with one’s friends and families, the transformative capacity of which is capable of lifting oneself out of life’s difficulties. Rogerson’s own poem within the collection, ‘The Minstrel’s Lot’, laments that the poet often goes ‘unpitied and uncar’d for by the crowd’ while living a humble and often difficult life, but is posthumously granted ‘an age of fame’, with people undertaking pilgrimages to their grave while the rich man’s grave lies forgotten. With any luck, our latest exhibition will re-enact the same fate that Rogerson foresaw for himself and his companions.

Blog post by Anna Pirie