- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Dr Dee: From Mortlake to Manchester

On 8 September 1597, the famed Renaissance polymath John Dee wrote to his friend, Sir Edward Dyer, to complain about the ‘tymes of very great dearth here … I can not see how my household of eighteen could live on the daily stipend of 4s … so hard & thinne a dyet, never in all my life, did I, nay was I forced, so long, to taste.’ At the beginning of the previous year, Dee had arrived in the town to take up the wardenship of its collegiate church, then known as Christ’s College, to which he had been appointed by Elizabeth I. Educated at Cambridge University, Dee had originally pursued a career at the changeable royal court, becoming Elizabeth’s astrological and scientific advisor, but when his proposals for calendar reform were rejected in 1583, he travelled to the continent and stayed at the courts of Europe. Upon his return in 1589, he discovered that his home of Mortlake had been ransacked and his cherished library sold to pay off his debts in his absence. He consequently sought financial compensation for his losses from Elizabeth, in whose gift the wardenship of Manchester’s college lay.

Chetham’s Library’s latest exhibition focuses on John Dee’s life and his connection to our buildings and the library’s collections. Although Dee hoped that the wardenship of the college would provide him with a consistent income and the chance to pursue his scientific studies uninterrupted, he found neither financial stability nor peaceful study during his tenure. Instead, he was continuously hindered by financial struggles, tensions with the college’s fellows, land disputes, and a persistent reputation for occult practices that followed him from the royal court to Manchester. He lost his wife Jane and potentially his three youngest daughters when the plague visited Manchester in 1604, and the following year, he quit Manchester and returned to his home at Mortlake (although he remained warden until his death in late 1608 or early 1609). Despite all of this, however, Dee was reasonably diligent in the exercise of his office, and was one of the last great wardens of the college before its seventeenth-century decline. Over the coming months, we look forward to exploring Dee’s life and experiences of Tudor Manchester with you.

On Friday 21 November, join us for an immersive after-hours event based on John Dee’s wardenship. Step into the college as Dee knew it, walk in his footsteps, and marvel at the books that he owned that are now part of the library’s collections (which are displayed together for the first time for one night only). You can find out more about the event and book tickets here.

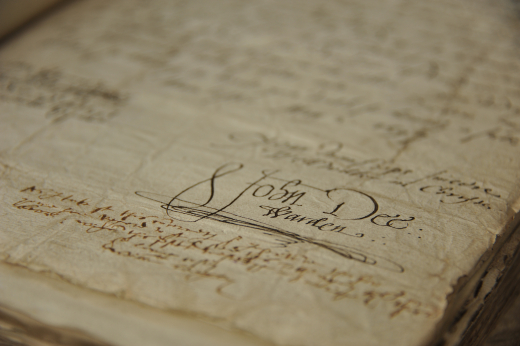

John Dee’s signature on a letter to William Langley, rector of Prestwich, dated 2 May 1597, concerning the bounds of the parish of Manchester (Chetham’s Library, Raines C.6.63, vol. 32, p. 9).