- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Not In front of The Children: Fairy Tales in Chetham’s Library

We’ve often heard Chetham’s Library described as a magic, fairy-tale place. Children, and many adults, gasp in disbelief and wonder as they ascend the stairs. Humphrey Chetham, with his grounded and far-sighted philanthropy, would no doubt have shrugged off such flights of fancy, but in the dusk of a winter’s evening it is possible to imagine the Library as the setting for a fairy tale – a story occasionally featuring fairies, but more often some combination of goblins, elves, trolls, witches, giants, talking animals, enchantments, and of course humans doing unspeakable things to each other.

A sampling of actual fairy tales in the Library revealed that one of the earliest volumes concerns Reynard the Fox. With his origins in a twelfth century legend, Reynard became the leading character in a 15th c book free of fairies but bursting with talking animals. Intended for adults, it turned into a best-seller and remained popular for more than 200 years. The story was characterized by violence, murder, adultery, rape and corruption in high places. William Caxton allegedly learnt Flemish in order to translate and publish the first English edition in 1481.

Roman de Renart (end 13th century). Illumination of the 1581 manuscript, Bibliotheque nationale de France

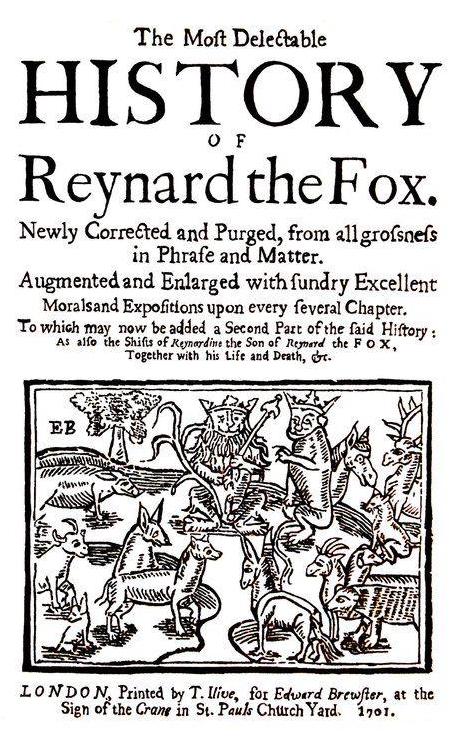

Chetham’s Library owns an uncommon ‘unpurged’ first edition of a later English translation: ‘Reynard the Fox: The crafty courtier; or the fable of Reinard the Fox printed in 1706. However, an another publication exists (not within our collection) from 1701, which had been published with a different slant. Subtitled: The Most Delectable History of Reynard the Fox. Newly Corrected and Purged, from all grossness in Phrase and Matter. Augmented and Enlarged with sundry Excellent Morals and Expositions upon every several Chapter.

The Most Delectable History of Reynard The Fox, 1701

A second part was appended: ‘Written For the Delight of young Men, Pleasure of the Aged, and profit of all. To which is added many excellent Morals.’ The fox has become quite domesticated. Children are not yet specifically mentioned as a target audience, but at around this time the advent of widespread chapbook circulation meant that children could, and did, avidly read and enjoy tales of impossible events and enchantment. One such, called Betty, was reported in the Spectator in 1709 as dealing ‘chiefly in fairies and springs’ for her reading material and ‘sometimes in a winter night she terrifies the maids with her accounts until they are afraid to go to bed’.

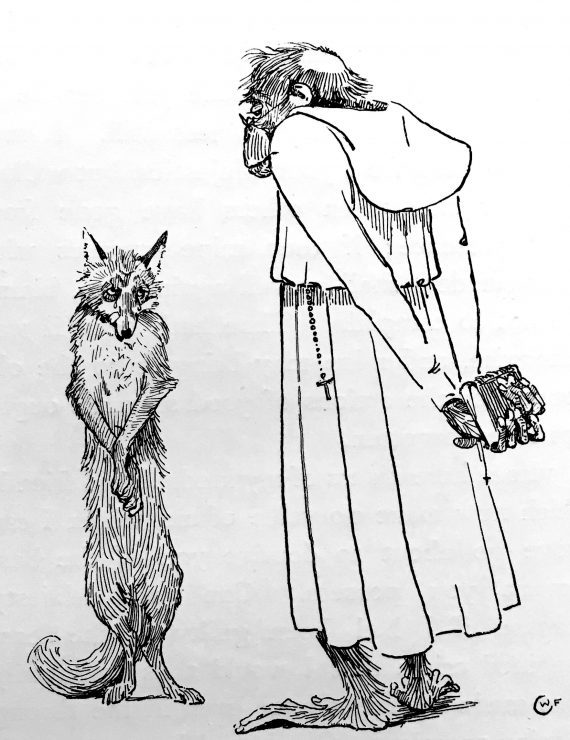

The Most Delectable History of Reynard the Fox. London, Macmillan & Co, 1895

The sanitation of Reynard continued during the 18th century, and by the mid-19th century he had become the hero of a reassuring fairy story where good and bad were easily distinguished and evil was punished in the end. Chetham’s Library has a copy of the children’s version: The Most delectable history of Reynard the Fox, by Felix Summerly, 1895, edited with introduction and notes (for adults) by Joseph Jacobs; done into pictures by W. Frank Calderton. Summerly was a pseudonym for Sir Henry Cole, a British civil servant and inventor, who, when not writing stories for children, was responsible for many innovations in commerce and education, including the concept of the Christmas card.

But did Summerly and Calderton just let Reynard hide his slyness and violent streak under a new furry and child-proof disguise? In other versions he was still allowed to appear as the stuff of nightmares. The various incarnations of Reynard illustrate the ambiguous and changing nature of fairy tales in literature and culture. The English Victorians were great believers in the fairy tale as a means of moral education rather than entertainment. John Ruskin wrote loftily that children have no need of such stories, but even he conceded that ‘they will find in the apparently vain and fitful courses of any tradition of old time, honestly delivered to them, a teaching for which no other can be substituted, and of which the power cannot be measured.’

The best-known collectors of fairy stories were of course the brothers Grimm; German academics, philologists, cultural researchers, lexicographers and authors. Between 1812 and 1864 Kinder-und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales) was published 17 times. Chetham’s has a later, English, edition of 1882.

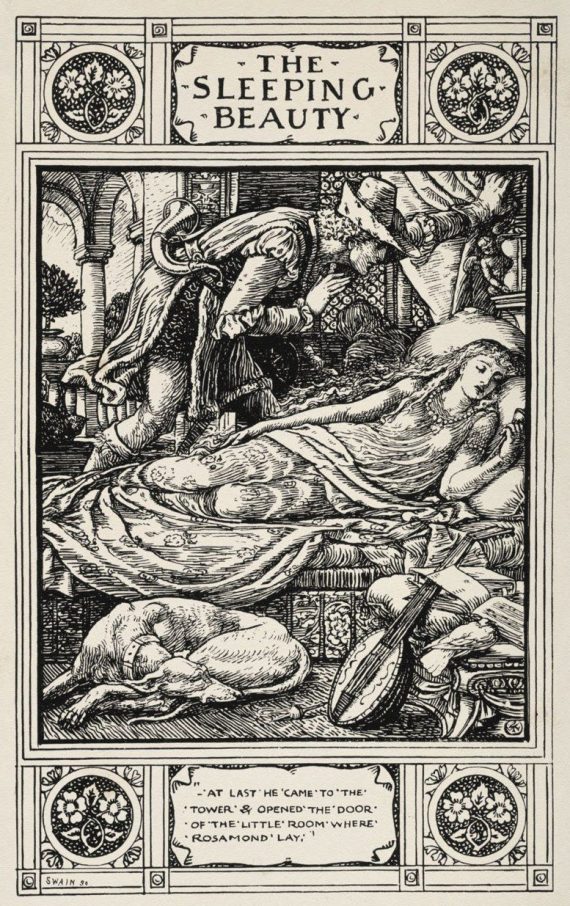

Crane’s illustrations, in the Pre-Raphaelites’ decorative style, turn the story into an irresistible romance. Whereas earlier versions of The Sleeping Beauty include an Ogress Queen, the Prince’s mother, who plans to eat the Princess and her children but is finally thwarted and thrown into a tub of vipers. The Brothers Grimm version was the first to introduce a swift happy ending with the Princess being awakened by a kiss.

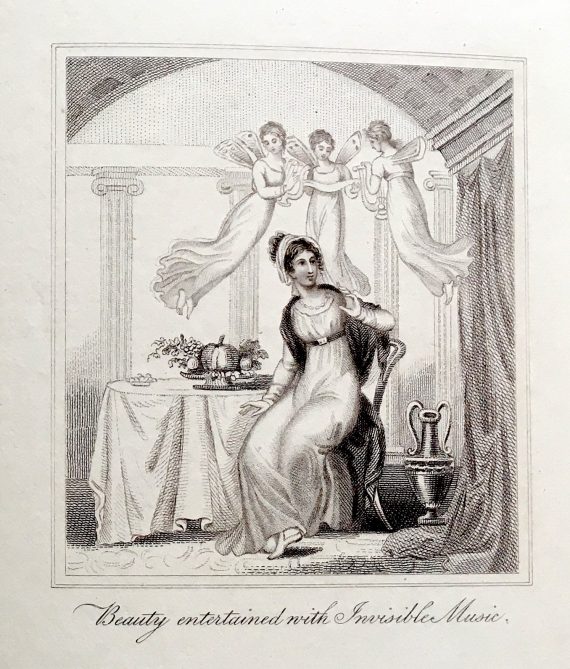

Beauty and the Beast, Charles Lamb. London: Field and Tuer, the Leadenshall Press 1887

Not all illustrators of the Brothers Grimm gave the stories such a romantic slant. We have a 1948 edition whose interest lies in the tortured illustrations by Joseph Scharl (1896-1954), a German Expressionist artist. His work was considered degenerate in Nazi Germany; he left Munich in 1938 and settled in New York, where he achieved modest success. This book of fairy tales published after the war met with huge public interest, but Scharl was unwell and burdened with worries for the family members he had left in Germany. He never returned and died at the age of 58.

Like the Brothers Grimm, Hans Christian Andersen caught the mood of his times; his stories were original rather than traditional re-tellings, readily accessible to children, but presenting lessons of virtue and resilience in the face of adversity for adults as well. Many of his tales reflect his own unhappiness as an outsider and a frequent sufferer from unrequited love. He did not always adhere to the increasingly popular convention of the happy ending.

Grimm’s Fairy Tales. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1948

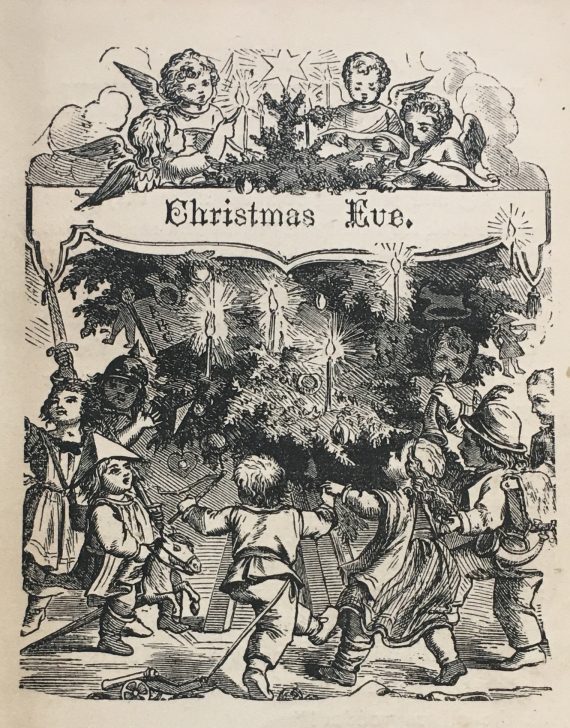

The Christmas Tree expresses a deep pessimism. It is a sad, sad tale of the life of a fir tree. The young tree is so anxious to grow up, so anxious for greater things, that it cannot appreciate living in the moment. It’s not until it’s chopped down for Christmas and then cast aside when festivities are over that it realises how good life in the woods once was. Despite a shaky start in life, Andersen had become a Danish national treasure by the time of his death. During his last illness he consulted a composer about the music for his funeral, saying: “Most of the people who will walk after me will be children, so make the beat keep time with little steps.”

The Christmas Tree & Other Stories by Hans Christian Anderson. London: Ward, Lock & Tyler 1800s

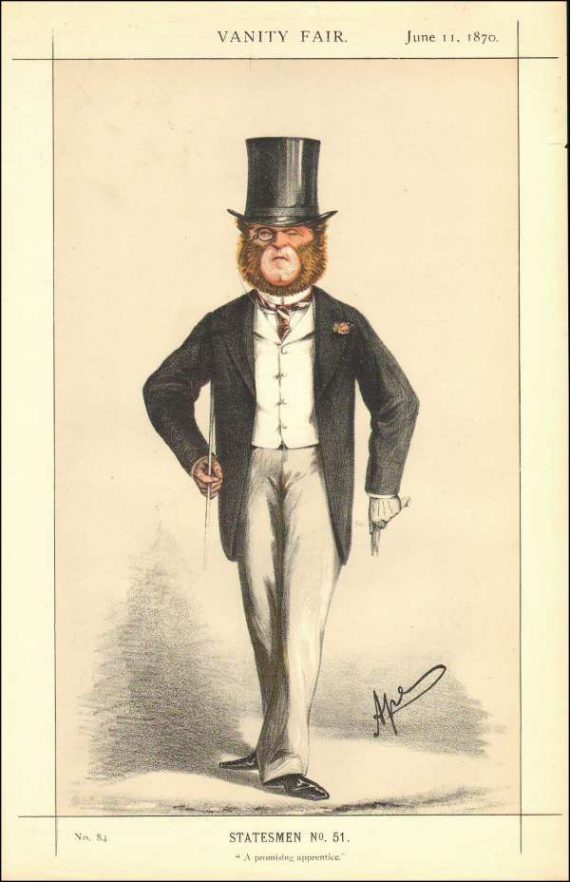

Back in Victorian England, more light-hearted but still not exactly child-friendly tales appeared in ‘Friends and Foes from Fairy Land’ by the grandly named Edward Knatchbull-Hugessen, Lord Brabourne, written in 1886. This English aristocrat and politician wrote many well-known short stories of fantasy and faery. He was widely likened by the reviewers to masters of the fairy-tale such as Grimm and Andersen, and his prolific output of the tales even led a critic at The British Quarterly Review to question his dedication to his job at the Colonial Office… “We should like to know whether Mr. Knatchbull-Hugessen maintains his intercourse with the fairies of the Colonial Office. If so, what department of office duty is specially favourable to them; whether, too, they come when Parliament breaks up, or whether their visits are intermittent all the year round.”

A Promising Apprentice. Knatchbull-Hugessen M.P. as caricatured by Ape in Vanity Fair, June 1870

Brabourne’s stories were less moralistic than some Victorian versions, but still contained their quota of violence and fantasy. J.R.R. Tolkien recalled that, as a small child, his bedtime reading was the fairy stories of Knatchbull-Hugessen. He remembered especially being read one story of an ogre who catches his dinner by disguising himself as a tree.

At around the same time as Friends and Foes appeared, a new version of Beauty and the Beast was published. This well-known story had been circulated in the 17th and 18th centuries, first as a fantastical romance for adults, then as a didactic tale for children about good manners and kindness. Some, rather unsettlingly, thought it helpful in preparing young girls for arranged marriages. The 1887 edition in Chetham’s Library, written in highly dramatic heroic verse, is said to be by the celebrated essayist Charles Lamb. His ‘Beauty’ was a creature of unalloyed sweetness, and the Beast was comfortingly soon tamed.

Beauty and the Beast by Charles Lamb. Field and Tuer, The Leadenshall Press, 1887

It seems, at least from our collection, that the market in Victorian fairy tales was cornered exclusively by men, and that most of these were distinguished in other fields – they were politicians, poets, serious literary figures, and humourists, able to command the services of respected artists and skilled engravers. Tom Hood, for example, was an English humorist and playwright, son of the poet and author Thomas Hood. In 1871 he produced Petsetilla’s Posy, an original fairy tale for young and old. A prolific writer, Hood was appointed editor of the magazine ‘Fun’ and founded Tom Hood’s Comic Annual in 1867. Frederick Barnard, his illustrator, was better known for his work with Dickens, and his printers, the Dalziel brothers, were London’s biggest and best known engraving firm who worked for the important writers and artists of the day, including many of the pre-Raphaelites. This was the golden age of illustration, and the Dalziels name appeared on nearly every major illustrated book published in Britain from 1840 to 1890. Together they went on to found The Camden Press.

In contrast to the relative gentleness of some mid-Victorian illustrated fairy tales, the library holds a collection of legends containing Jeremiah Gotthelf’s 19th century gothic horror, ‘The Black Spider’. A young woman makes a pact with the devil, sealed by a single kiss, which brings generations of terror to her community. The destruction of the evil caused by that kiss is the basis of a creepy and frightening story.

Traditions and Legends of the Elf, The Fairy and the Gnome. London: T.Ricardson, Printer ca 1890

Ronald Firbank was a well-connected and innovative English novelist who took the fairy tale to new levels. His eight novellas, partly inspired by the London aesthetes of the 1890s, especially Oscar Wilde, consist largely of dialogue, with references to religion, social-climbing, and sexuality. His books describe a whimsical universe peopled with bizarre characters and are noted for their elegance and wit. Odette, a Fairy Tale for Weary People, published during the first world war, was definitely not one for the children.

A more recent tiny treasure held in the library, originally published in our 1970 first edition by the Royal Academy of Arts, features David Hockney’s weird and wonderful drawings to illustrate six fairy tales. Traditional images of the genre tend to rely on beauty and colour to create magic and contrast the beautiful and the ugly so as to distinguish between good and evil. But in Hockney’s version even the princesses in the black-and-white illustrations are unassuming, even ugly. His haunting, scary, architectural illustrations reinforce the idea that, though fairy tales might have been doctored over the ages to appeal to the young, they still have the potential to be “Too Grimm for Children.”

Blog written by volunteer Kath Rigby

4 Comments

Jean Tarry

I loved this post – very interesting, especially as I was musing on an old nursery rhyme that I had learnt when I was little about piglets dying of felo de se!

But to return to the blog: I was intrigued by the first image of the two animals in combat. I couldn’t make out what was happening at the back end of the dark brown horse. What are those 2 things that look to me like the top of crutches? And what is in the bag?

ferguswilde

Thanks, Jean, glad to hear you enjoyed the post – the two things that look like crutches are the tops of left-hand-beast’s war saddle, designed to hold him firmly in place through the shocks of combat, particularly charging with the lance. I’m pretty sure that what looks like a bag is just the way the artist has realised the horse’s caparison, which would have protected the horse in combat.

Geraldine Beare

Great blog – thanks! Fairy tales seem to attract a wide variety of illustrators from William Heath Robinson to Paula Rego; Arthur Rackham to Quentin Blake and all shades in between and beyond. A.S. Byatt wrote an interesting article 15 years ago on the 200th anniversary of Hans Christian Andersen’s birth in which she mentions the Brothers Grimm, E.T.A. Hoffmann but not Charles Perrault who seems to have been the ‘father’ of the genre.

Daniel Yates

I recently published a book on Robert Kirk’s secret commonwealth. With so much related materials I feel a booking in the reading room coming on!