- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

William Hogarth talk

Public talk on the art of William Hogarth, 8 March 2023

William Hogarth’s paintings and prints are for many the very image of eighteenth-century England. His ‘Gin Lane’ and the parallel, ‘Beer Street’, are worthy of the over-used adjective ‘iconic’ when it comes to imagining the London of the 1700s. In Chetham’s Baronial Hall on Wednesday 8 March, using images from Chetham’s own extensive collection of Hogarth prints, expert Dr Noelle Duckmann Gallagher of the University of Manchester will take us through his earliest ‘hit’ series of prints, the Harlot’s Progress. Drawing attention to the many visual references not immediately obvious to the modern eye, and the dark humour that pervades them, she will set them in the context of the often raw, rough and ready life of the capital under the Georges. All proceeds to help support the Library’s work. Book your tickets here!

Come and follow the adventures of Moll Hackabout!

Keeping our Hogarth collection busy this March, the Library is also lending prints from its collection to Derby Museum and Art Gallery for their upcoming exhibition on Hogarth’s response to the threat from the 1745 Jacobite rebellion. The exhibition will open on 10 March.

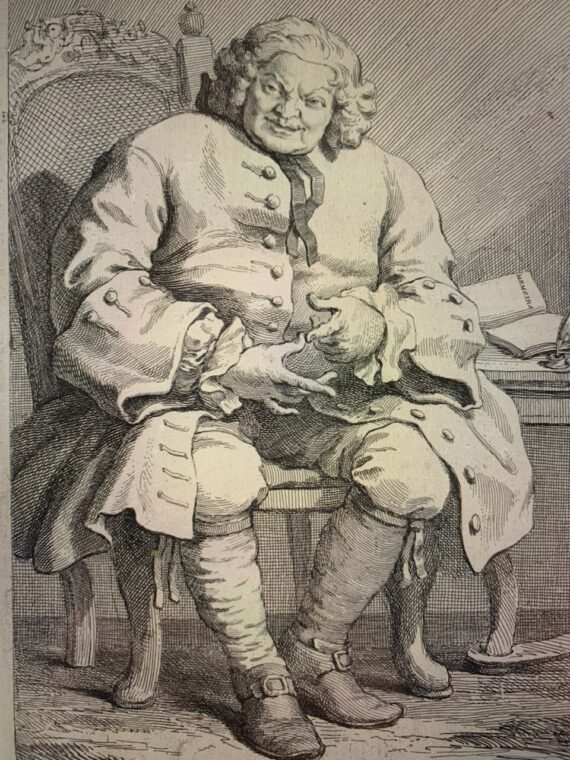

Our copy of Hogarth’s portrait of Simon Fraser, eleventh Lord Lovat a Jacobite conspirator, after he was arrested in 1746 Lovat was brought to London for trial. Hogarth arranged to meet him at the White Hart Inn to interview and draw him. On 9 April 1747 he became the last man to be beheaded in England.

William Hogarth, artist, engraver, satirist

We hope you’ll be able to attend the talk; but who is our subject? William Hogarth was born on 10 November 1697. His father was a teacher and writer from Westmoreland, whose business ventures failed and led him to be imprisoned for debt. This family disaster led to William’s education being curtailed, and he was sent into an apprenticeship with a silver engraver, in which he learned many of the skills that would serve him as an engraver of fine arts. His ultimate ambition was to master oil painting, seen by him and his contemporaries as the highest form of the artist’s profession. By the 1730s he had indeed established himself as an artist, predominantly focusing on portrait groups, known as ‘conversation pieces’, typically full-length oil portraits of groups of people.

Changing artistic direction in 1731, he created a series of paintings satirising contemporary customs and mores, or what he referred to as ‘modern moral subjects’, the first being ‘The Harlot’s Progress’, followed by ‘The Rake’s Progress’ and ‘Marriage à-la-Mode’. These were pictorial narratives of contemporary life in the eighteenth century with a sharp satirical bent, out of which none of the subjects depicted emerges with much credit. Despite – or perhaps because of – this misanthropic turn, the sets sold well and brought him fame.

Detail from the first scene in the ‘Rake’s Progress’ : Tom Rakewell, the chief protagonist, inherits his father’s money and is soon surrounded by those keen to help him spend it – on themselves.

Six spendthrift plates later in the series, however, the end has come :

In the eighth and final engraving of A Rake’s Progress, anti-hero Tom Rakewell is now in Bethlem Hospital (Bedlam), London’s infamous mental asylum, having been driven mad by his self-inflicted fall into penury. Only Sarah Young, the mother of his illegitimate child is there to comfort him; the well dressed women in the back have come to the asylum for entertainment.

The success of these series was such that they were immediately copied by others, not just in print but through theatre, china, pamphlets, and even ladies’ fans. His work was so plagiarised that he lobbied for the Copyright Act of 1735 to protect writers and artists, leading the legislation to be nicknamed the ‘Hogarth Act’.

Hogarth’s themes were not invariably dark or satirical. This detail shows a part of his plate for Shakespeare’s Henry VIII, based on a contemporary production from 1727 by Colley Cibber’s company. Cibber himself played Cardinal Wolsey, and a Mr Booth played Henry, who is shown here admiring Anne Boleyn.

Throughout the 1730s and 1740s, Hogarth garnered more fame and his reputation grew. His work reflected his passion for social and moral reform, and this propagandist tone was directed towards London and the city’s problems with crime, prostitution, gambling, and alcoholism. This reforming note is reflected in Industry and Idleness (1747), Beer Street and Gin Lane (1751), and The Four Stages of Cruelty (1751). The Four Stages condemned life in the capital as tending towards a progression from animal cruelty (inspired in part by press reports) as far even as murder, followed by society’s own cruel response of hanging and ultimately sending the body of the executed criminal to the dissecting table.

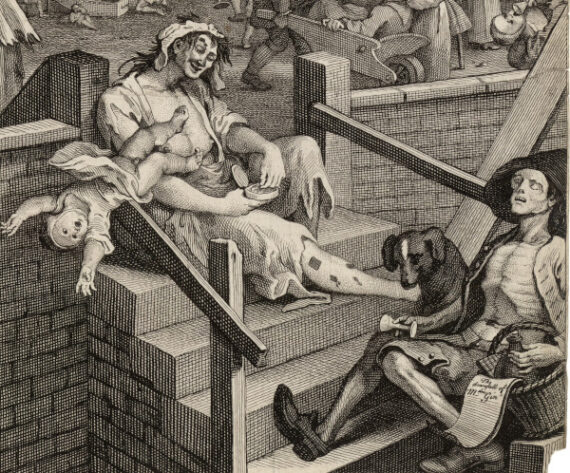

Those who live in Gin Lane are shown as destroyed by their addiction to the foreign and corrosive spirit, gin, with shocking scenes of infanticide, starvation, madness, decay, and suicide, while Beer Street contrasts in depicting relative industry, health and thriving commerce.

On Beer Street, the people may not be the ideals of 18th-century beauty, but their plumpness and relative good humour, with full tankards and joints of meat, fulfil the promise of the caption in the engraving, which begins : ‘Beer, happy Produce of our Isle …’.

A less than flattering view of an eighteenth-century night with the boys, ‘A Modern Midnight Conversation’.

From the start of his career, Hogarth despised the predisposition of the art world patrons and connoisseurs to favour foreign artists. This dislike was illustrated in one of his early major works, Masquerades and Operas, published in 1724. Here he attacked contemporary taste and questioned the standards of the circle that was supported by the 3rd earl of Burlington, a highly influential art patron and architect, whose London home is named ‘Academy of Arts’ in the print. Having angered such powerful figures at the start of his career he would be obliged to work almost entirely outside the academic art establishment; however, through his success the popular art market and the role of the artist would be revolutionised.

The satirical print ridiculing the ‘reigning follies’ of fashionable London that so angered the art world of the day. At the centre is a waste-paper carrier, whose barrow is filled with the great names of British literature. Crowds queue for entertainments in ‘Bad Taste’, with Burlington House in Piccadilly named the ‘Academy of Arts’. Italian opera is ridiculed in the figures of the fashionable opera singers Francesca Cuzzoni, Francesco Bernardi (Senesino) and Gaetano Berenstadt, who are shown on a large banner performing Handel’s ‘Flavio’. The devil himself leads those seduced away from Shakespeare and the English greats into the Masquerade.

Hogarth strove to create works of great beauty, but also to create work that would help to improve his home city of London. His willingness to satirise individuals, erstwhile friends as well as enemies, kept him from peaceful enjoyment of the fame his body of work had gained him; he remained in the good opinion of George III, and thus had friends at court, and had friends such as the theatre impresario David Garrick, but fell out with John Wilkes, Horace Walpole, and others of great influence in quarrels and spats that were unresolved at his death in 1764. His complex, fascinating and often amusing life is beautifully captured in Jacqueline Riding’s Hogarth : life in progress (London : Profile, 2021), which we heartily commend to readers.