- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Manga among the manuscripts

Another guest post from our most excellent volunteer and great friend of the Library, Patti Collins.

One of the delights of the library is that the most unlikely items often turn up amongst its collections, often as the result of donations. Over the years, the Library has accepted donated collections from various individuals, which can bring with them a wide range of material, depending on the enthusiasms of the particular collector.

So, despite our official policy of collecting historical material on Manchester and the north west of England, after watching the recent excellent series of television programmes on Japanese art, I decided on a whim to check our catalogue, just in case we had anything on Japanese art and specifically on the famous painter Hokusai.

I was thrilled to see that we had indeed got items attributed not only to to Hokusai, but also to Hiroshige and other Japanese artists. After locating two boxes I began to explore.

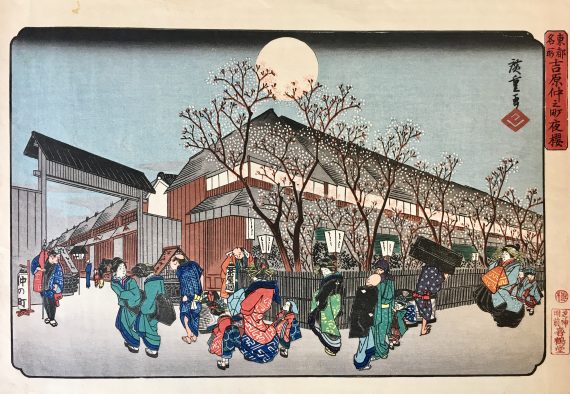

The first box contains an assortment of richly coloured, large, woodcut prints with subjects ranging from warriors and actors to birds, fish and a lively scene set in a Red Light district, which we believe is by Hiroshige.

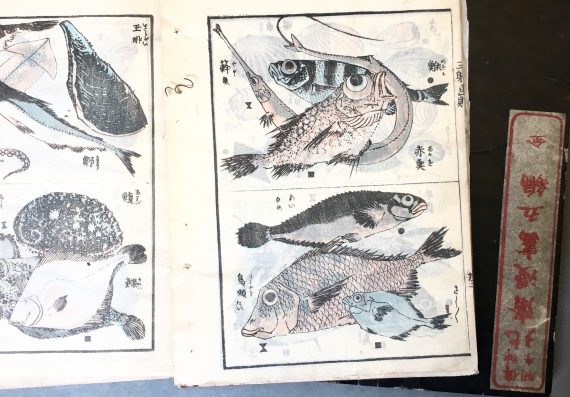

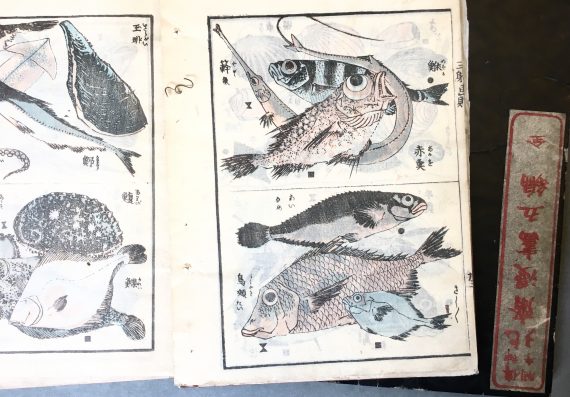

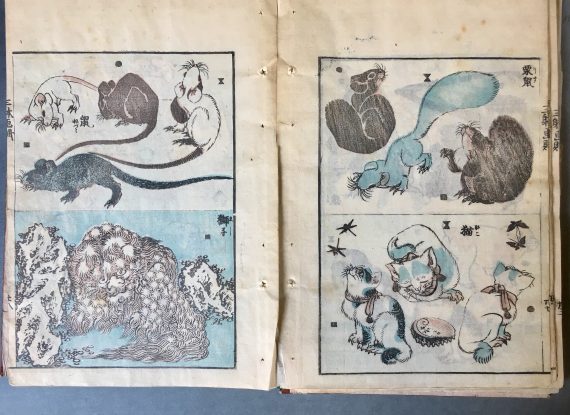

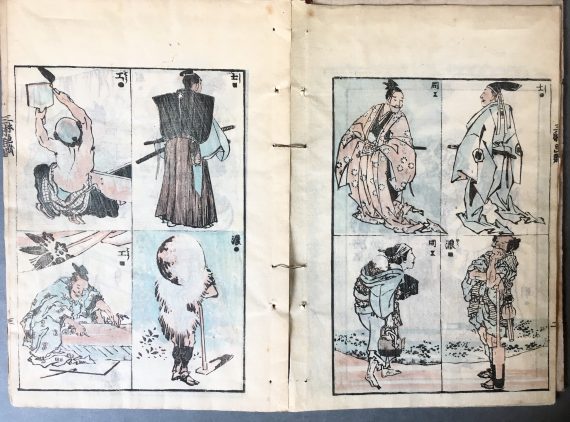

The smaller box contains several paper covered printed books of sketches or ‘manga’ – cartoon-like drawings, in faded colours, several to each flimsy page. The paper is so thin that, even folded, the drawings on the other side are visible. The word ‘manga’ comes from the Japanese words meaning ‘whimsical or impromptu’ and ‘pictures’. (Our modern usage, which refers to Japanese comics, cartoon style drawings and animations, began in the 1950s.)

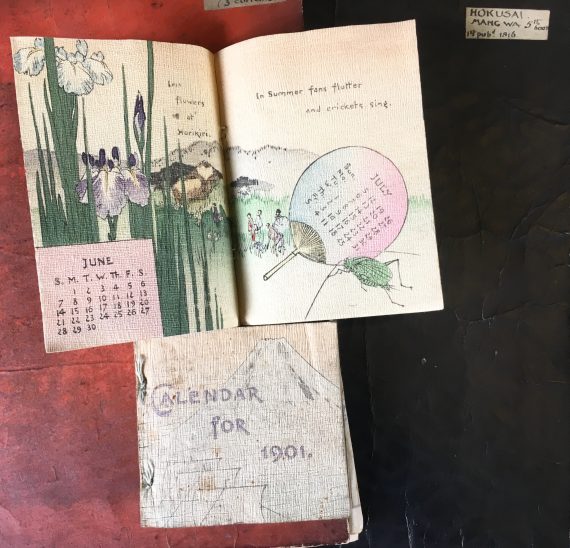

The word ‘manga’ first came into common usage in the late 18th century to describe a certain style of popular picture books, and amongst the earliest were the celebrated Hokusai Manga books (1814–1834). Hokusai was only persuaded to publish the first volume of assorted sketches as he was in a dire financial situation, but it was an immediate bestseller and eventually 14 volumes were published.

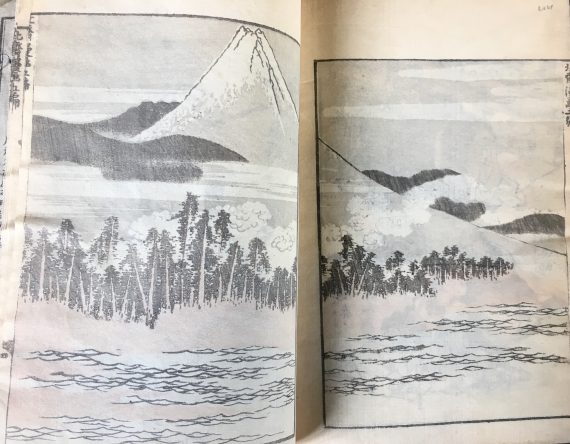

The images are a cornucopia of people, animals, landscapes, buildings, insects and an assortment of comical figures. Among the drawings in the earlier volumes, are Hokusai’s early experiments in portraying Mount Fuji at different angles and in different contexts, years before his famous print series, ‘Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji’ was published.

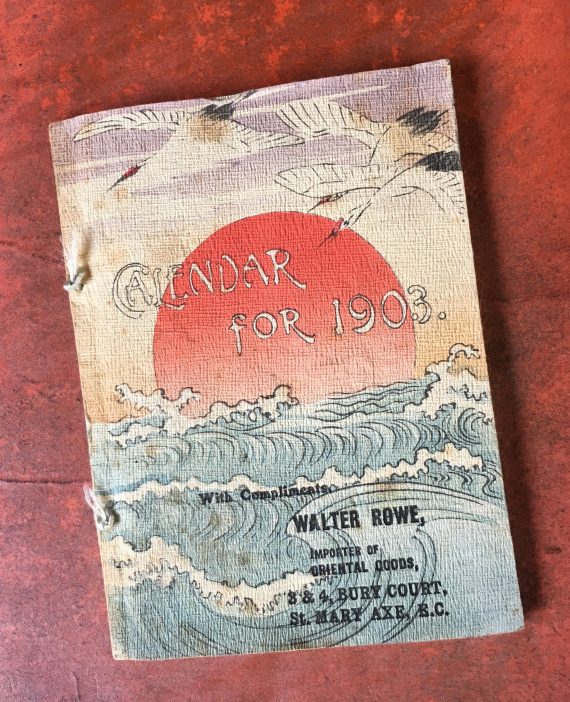

So… why on earth do we have Japanese manga in a seventeenth-century library? Well, in one of the boxes are two tiny calendars from 1901 and 1903, presumably designed to promote a business importing Japanese products to the UK – which is a clue to where the collection originated.

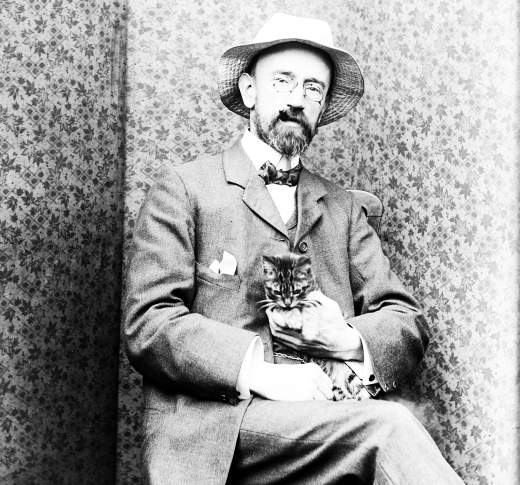

The answer lies in the donation to the library of the collection of Joseph James Phelps (1855-1928). This includes over twenty boxes of notes and correspondence on the archaeology and early history of Manchester, plus cuttings and illustrations. It also contains a large collection of glass negatives and lantern slides from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, covering a range of local history subjects including canals, industrial development, architecture, family portraiture, street life and city views.

Phelps was originally a Manchester businessman but became well known as an amateur archaeologist, photographer and antiquarian. He also volunteered at Chetham’s Library for many years, even acting as a temporary Librarian during the First World War. According to John Gandy’s 2003 article (in Transactions of the Lancashire and Cheshire Antiquarian Society, Volume 99) Phelps had a strong interest in Japanese art and culture, possibly originating in his early career as a partner in a business which specialised in lamps and lamp fittings and also imported high class brass and copper fancy goods. He owned Japanese books, and other items including prints and seemed to have some knowledge of the Japanese language.

You can read more about Phelps on our website. Here he is with a furry friend.