- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Of Eggs, Shee-Spies and Aphra Behn

Following on from our last blog, here is an example of spycraft from the 17th century.

To put a Schedule, or lytle wryting into an Egge, lay an Egge certaine days in strong vinegar, until it be soft, and wryteyour name or what you lyst in a lytle peece of paper, and folde the paper as harde together as you can: then with a Raser, cut the sayd Egge in the toppe finely, and advisedly; through the which, putt the lytle paper into the Egge cyrcumspectedly, and then put the Egge into cold water, and immediately the shell wyle be harde as it was before. A proper secrete.

Hiding messages in eggs, creating invisible ink from artichoke juice, smuggling notes in their skirts, cracking codes; these were all in a day’s work for more than sixty female spies in overlapping networks in 17th-century England. Monarchs and governments employing spies to safeguard their regimes saw that women had certain advantages in the game. They were generally excluded from politics and considered at the time to be too irrational and undependable to be agents, which is exactly why they were perfect for the job. They did not arouse suspicion, were not searched when travelling and, presumably, were patient enough to hide little notes in eggs and ingenious enough to make use of such arcane subterfuge.

So why was the ancient art or science of spying so crucial in the mid to late 17th century? The restoration of Charles II to the throne of England in 1660 did not mean stability was magically restored after twenty years of political turbulence. Rumours of republican conspiracies were rife, there were problems with the community of parliamentarian exiles in the Netherlands, and commercial and naval rivalry had already resulted in war with the Dutch. To survive and prosper, the new regime found it necessary to deploy spies and informers to penetrate and betray any potential plots and gain secret knowledge of foreign affairs. Despite his cheerful deportment, Charles II, the Merry Monarch, was a worried man.

Charles II dancing at a Ball at Court, c 1660. Hieronymus Janssens (Flemish, 1624-93). Berkshire: Windsor Castle, RCIN 400525. Source: Royal Collection Trust

This particular espionage tale starts in Surinam, an English plantation colony utilizing slavery for sugar cultivation, much coveted by the Dutch. Even in such distant colonies, people of suspicion were under surveillance. One of these was Robert Scott, son of a regicide, who played a double game in an uprising before the Restoration and had known ties to England’s number one enemy. Also there, according to her (not altogether reliable) memoirs, was Aphra, a young woman going under the name of Astrea, who was eventually expelled by the Deputy Governor, possibly because she was suspected of being a royalist spy. Somewhere between this expulsion and 1665, Aphra married a shadowy, probably German, figure by the name of Behn, who promptly disappeared from the records.

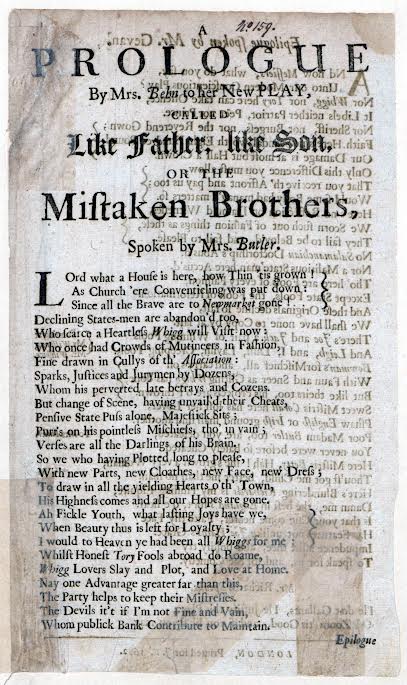

In 1666, the first record of Mrs Aphra Behn appears, she was to become a celebrated playwright, poet, translator, and one of the first English women to earn a living by writing and became a literary role model for later generations of female authors. Virginia Wolf famously wrote of her: ‘All women together ought to let flowers fall upon (her) tomb…for it was she who earned them the right to speak their minds.’ Much of Behn’s work is easily available today in modern editions, but Chethams Library holds some rare first edition fragments – two translations, a prologue to a play by John Fletcher, and her own prologue to her late, probably unpublished, play ‘Like Father Like Son or The Mistaken Brothers.’

Aphra Behn’s Prologue to her play ‘Like Father Like Son,’1682, in Chetham’s Library.

But to get back to the spy story, Aphra records in her memoirs that she had an audience with Charles II after her return to England. Such a meeting seems unlikely for the daughter of (allegedly) a barber and a wet nurse, unless either she had taken his fancy, or, more probably, unless she was an agent with news to report. It may be that by this time she had already made inroads in the world of theatre and politics and that her services were recruited by Thomas Killigrew, the dramatist heading up the King’s Company and secretly working in intelligence for the King. However she was recruited, by July 1666, during the darkest point of the Second Anglo-Dutch War, she finally enters recorded history as the subject of a document issued by the office of the Secretary of State, Lord Arlington, entitled ‘Memorials for Mrs Affora’ and giving her a 14-point list of instructions. And so she embarked on a short, frustrating, dangerous and ultimately unprofitable career as a spy: Agent 160, Code Name Astrea.

By this time Robert Scott had left Surinam, was lying low in Holland and was suspected of working for the Dutch. Aphra was charged with finding him and then ‘to know whether Mr Scott has any resolution to become a convert and to serve his KING and COUNTRY. To use all secrecy imaginable.’ She was to extract information on how many ships the Dutch had, how many had been lost in a recent skirmish, whether and when they would ally with the French, what the private Dutch East India Company fleet was doing and the whereabouts of other merchant ships. Additionally, she was to discover anything at all about Dutch spies operating in England, whether the English exiles in Holland would invade and if so where they would land. Any information was to be relayed in code to Arlington. The code was not complex: 160 for herself with the cover name Astrea, 159 for Scott, whose cover name was Celladon, 26 for Amsterdam and so on. We can assume that Aphra had some kind of cover story and there is evidence that she was accompanied by a MrPiers, a merchant sailor.

Distant View of Antwerp,17th century, Hans Bol. WA1863.149 © Ashmolean Museum.

In return for such intelligence, acting as a double agent, Scott was to be offered both money and a pardon for his earlier misdemeanours against the new regime. Arriving in Antwerp in Flanders, rather than hostile Holland, Aphra wrote to Scott asking for a meeting. Surprisingly, he agreed immediately, perhaps because he already knew her from their days in Surinam or perhaps because he was tempted by the offer of money. She does not seem to have been pleased to see him. ‘I was forced to get a coach and go a day’s journey with him to have an opportunity to speak with him, …’ but she felt she had been successful: ‘After I had used all arguments to him that were fit for me, he became so extremely willing to undertake your service.’ She, naively as it turned out, felt she had gained his trust: ‘I really believe [his] intent is very real and will be very diligent in the way of doing you all the service in the world for the future.’

The National Archives holds 19 of Aphra’s spying letters sent to London from Antwerp. We learn that Scott did write several letters with snippets of information but it seems Aphra copied out the first few to send to Arlington’s office, and kept the originals, claiming that Scott was afraid to have his own handwriting recognised if the letters were intercepted. Some scholars believe she rewrote the letters to make the intelligence sound more important than it really was, with the occasional comment on what English policy should be. Others have suggested that the letters were the early attempts of a budding fiction writer and they contained half-truths based on her own eavesdropping, reading of newspapers and imagination. In any case, Scott refused to divulge more unless he was paid and his pardon assured, and unless she came to Amsterdam, which was safer for him, but highly dangerous for Aphra – she ‘dare as well be hanged as to go’, particularly as the English had just burnt some of the Dutch fleet in its own harbour and anti-English feeling was raging.

The Four Days’ Battle, 1-4 June 1666. Abraham Stock. Wikipedia.

In the next few months, this spying life became increasingly uncomfortable and dangerous for Aphra. She had unwisely shared her credentials with a failed English spy, Thomas Corney, who had earlier been betrayed by Scott to the Dutch government, imprisoned and tortured, dropped from Arlington’s payroll, and was seeking his revenge by undermining the ‘shee spy’, as he called Aphra. Both he and she were somehow able to access each other’s correspondence and he insulted her to everyone he knew. He suggested Scott and Aphra were lovers conspiring to swindle Arlington and that the whole mission was hopeless. Back in London letters were arriving from both Corney and Aphra, each claiming that the other was indiscreet, and both begging for money.

Indeed, whatever Aphra’s shortcomings as a spy, she needed money to live, and instruction to continue to ensure Scott’s trust. ‘I have sent several times to Mr Hallsall,’ she wrote, ‘but I can get no word of answer…I have by this post sent him things from Celladon who is the readiest man alive to serve his majesty… without any encouragement than barely my word.’ Her frustration is palpable. ‘I confess I carried no more … but 50 pounds and I have not only spent all that upon mere eating and drinking but in borrowing of money to accomplish my desires of seeing and speaking with the man. I am as much more in debt having pawned my very rings.’

As the months passed she feared she had lost the trust of Scott due to Corney’s intervention, and she needed money to pay her debts and return to England. She wrote to Arlington himself: ‘Therefore my humble petition to your lordship is that I may have a final answer of what I am to do, and not let me be disgraced and ruined in a strange place where I have none to pity or help me.’ There was no immediate answer. Eventually Scott, always under surveillance by both sides, was arrested by the Dutch (after which he disappears from the record), and the mission was clearly at an end. At last, Aphra received enough money to pay her immediate debts and return to London in May 1667.

Even after she returned, she had debts to pay, a warrant was issued for her arrest, and she was forced to ask her former employers for help. No amount of pleading could induce the English government, now on the verge of bankruptcy, to give her more. Hearing nothing, she petitioned the King. Thereafter her name as an agent disappears from the records, either because the petition worked or because she served her time in a debtors’ prison, but within a few years she had built a reputation as a writer, still using her pastoral pseudonym of Astrea, and her plays were wildly popular on the stages of Restoration London.

Aphra was just one of many women who, for reasons of pride, financial gain, ambition, love or adventure, undertook roles as secret agents for their King and country, at great risk and cost to themselves. In her case, at least part of the motivation appears to have been a genuine devotion to the Stuart cause. Despite her shoddy treatment in the King’s service, she revered Charles II, and subsequently supported his brother James II, dedicating a play to him even after he had been exiled. Just before she died, she declined an invitation to write a welcoming poem for the new monarchs, William and Mary. Had she lived she would have been an enthusiastic advocate of the Jacobite cause and would no doubt have deployed her now powerful pen in its service.

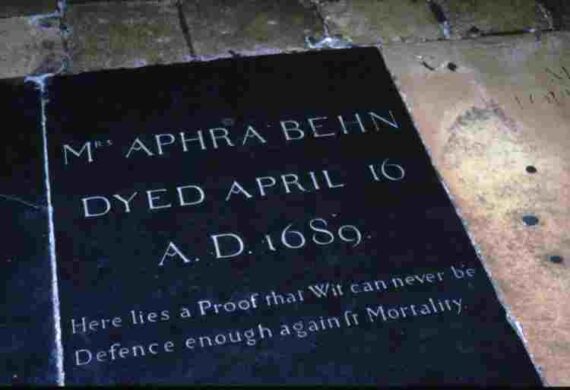

Aphra Behn’s talent had not been dampened by her dispiriting experience as a secret agent; her exuberant works in poetry and prose, sometimes serious and lyrical, sometimes bawdy and erotic, speak of power, politics and religion, women’s rights, colonial oppression and slavery. Some of her plays were so popular that they were on stage in London every season for decades after her death. Although she had not been clever enough to survive in a wartime spy network, she later personified that highly valued 17th attribute – ‘Wit.’ Her memorial in Westminster Abbey regrets: ‘Here lies a proof that Wit can never be/Defence enough against Mortality.’

Gravestone of Aphra Behn (east cloister)© Dean and Chapter of Westminster.

Sources

Nadine Akkerman, ‘Invisible Agents: Women and Espionage in 17th Century Britain’

Janet Todd, ‘Aphra Behn: a Secret Life’

National Archives project, ‘Aphra Behn: Memoirs of a Shee Spy. Katy Mair, Elaine Hobby

By: Kath Rigby.

NB In July 2024 the Guardian promised ‘joy at the celebratons of Aphra Behn: a Netflix film, statue and a newly discovered first edition. These have yet to materialise.