- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Reform and repression – the Hay Scrapbooks

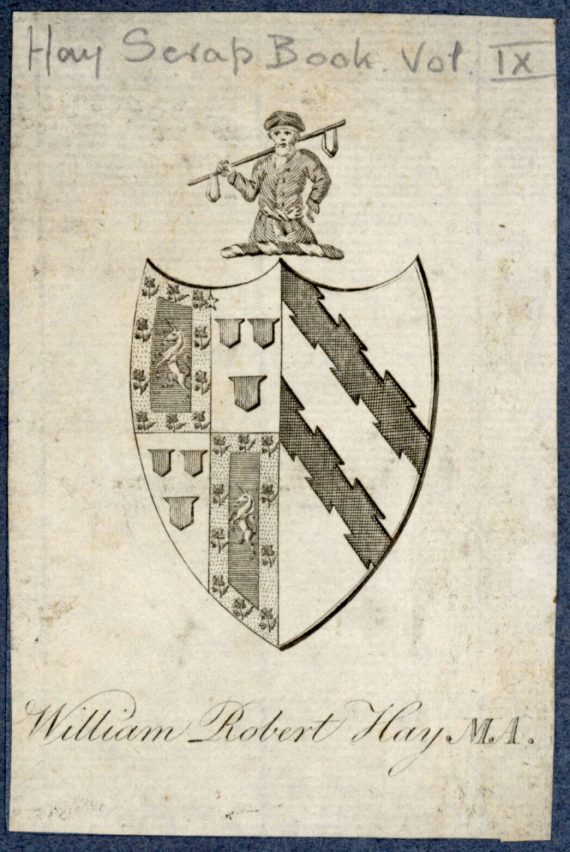

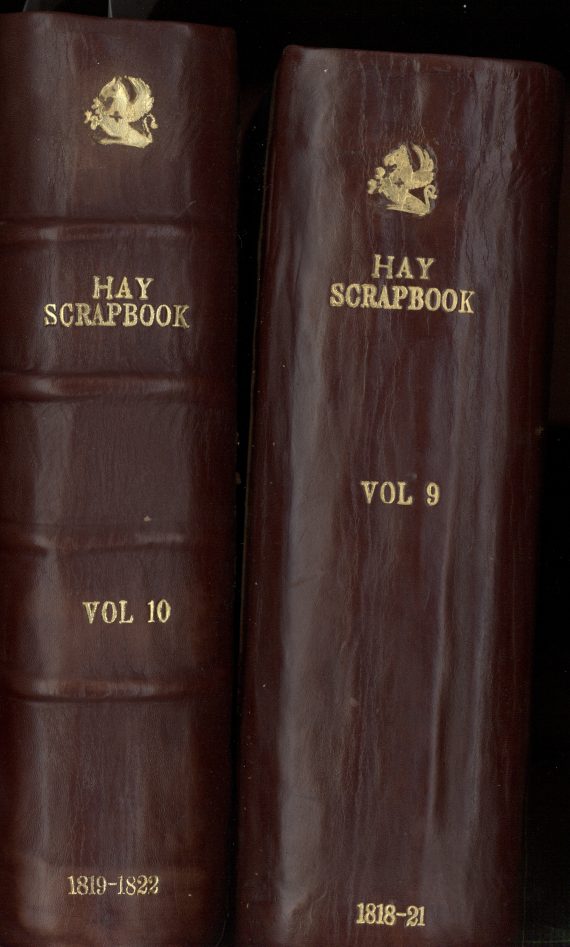

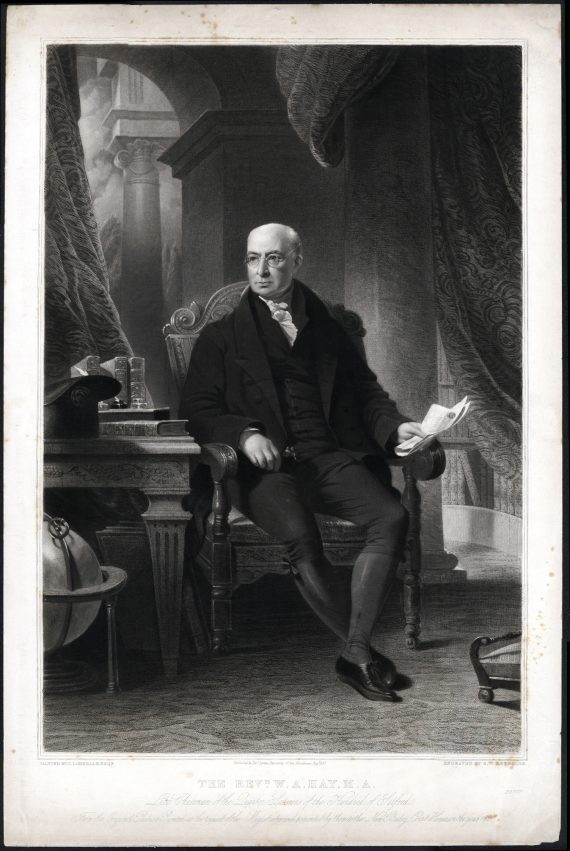

Almost 200 years after the Peterloo Massacre, we can read contemporary press reports of this horrific event in Chetham’s Library’s Hay scrapbooks, which have just returned from a much needed renovation, kindly funded by the National Manuscripts Conservation Trust and the Pilgrim Trust. The 17 volumes of scrapbooks contain thousands of newspaper articles, letters, accounts of church proceedings, poems, advertisements and random ephemera collected by the anti-reformist Reverend William Robert Hay (1761 – 1820), an unsuccessful barrister turned clergyman, chair of the Salford Quarter Sessions and scourge of radicals and reformists.

Volumes 9 and 10 primarily cover 1818 – 22, a period of radical ferment in which agitators demanded more rights and power for working people and universal suffrage. Hay vehemently opposed the radicals, backing government measures to repress dissent and even, it is rumoured, running a network of spies and informers.

The scrapbooks, which focus on Manchester, offer a fascinating insight into radical reformist activism in these years and the attempts of the establishment to quash it. Hay often collected multiple reports of the same event in which, as today, the political allegiances and biases of the different sources are evident. The Manchester Chronicle, for instance, a Tory paper which opposed social reform, referred to the ‘seditious activities’ of the ‘mobs’ whereas the Manchester Observer, a paper with a literate working class readership who supported parliamentary reform, was sympathetic to the radicals.

The scrapbooks contain press coverage of the Peterloo massacre and the subsequent persecution of the the leaders. Manchester citizens were still disenfranchised in 1819 when 80.000 people gathered in Manchester on 16 August 1819 to demand parliamentary representation. Hay and other magistrates ordered the cavalry and yeomanry to charge into this peaceful protest. They rode into the crowd wielding sabres, killing 15 people and injuring hundreds of women, men and children. This act, which we know as the Peterloo Massacre, horrified many but Hay, like sections of the press, presented the peaceful crowd as potentially violent in order to justify the actions of the cavalry:

‘We have received such information from the most authentic sources, respecting the principles, objects, and character of the miscreants who assembled on the 16 August at Manchester that fully justifies all the measures to which the authorities Civil and Military were obliged to report on that memorable as well as lamentable occasion that details how that rabble were armed and prepared to overpower any Civil and Military force that could be brought to oppose them.’

The government commissioned Hay to report on the day’s events, and two days after the massacre he delivered an account to Lord Sidmouth, the Home Secretary which gave total and unconditional support to the magistrates and cavalry, defending their actions and showing no compassion for those who were mown down. Hay was one of the magistrates who ordered the arrest of Henry Hunt, John Knight, Joseph Johnson and James Moorhouse after the Peterloo massacre, and he collected newspaper reports of Henry Hunt’s trial and guilty verdict at York Assizes. A few months after the Peterloo massacre Hay was appointed rector of Rochdale, one of the most lucrative livings in England, as a reward for his support of the establishment during and after Peterloo.

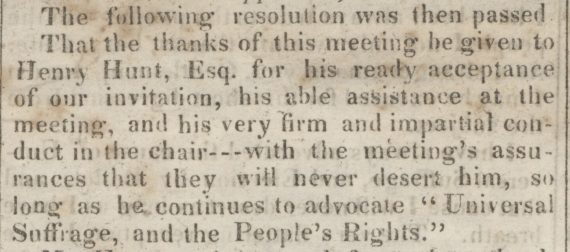

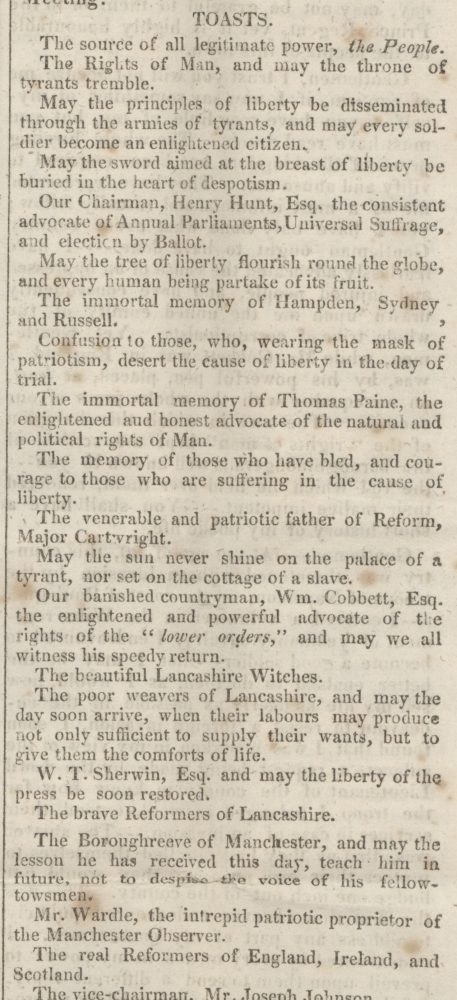

The government responded to the wave of popular protest following Peterloo by passing new legislation, known as the Six Acts, which prevented outdoor public meetings and gagged radical newspapers and writers. Hay’s newspaper cuttings report meetings in great detail and often contain verbatim reports of speeches, such as Henry Hunt’s address to radical reformers commenting on the iniquity of Peterloo and the proposed laws to curtail freedom of speech and liberty of the press.

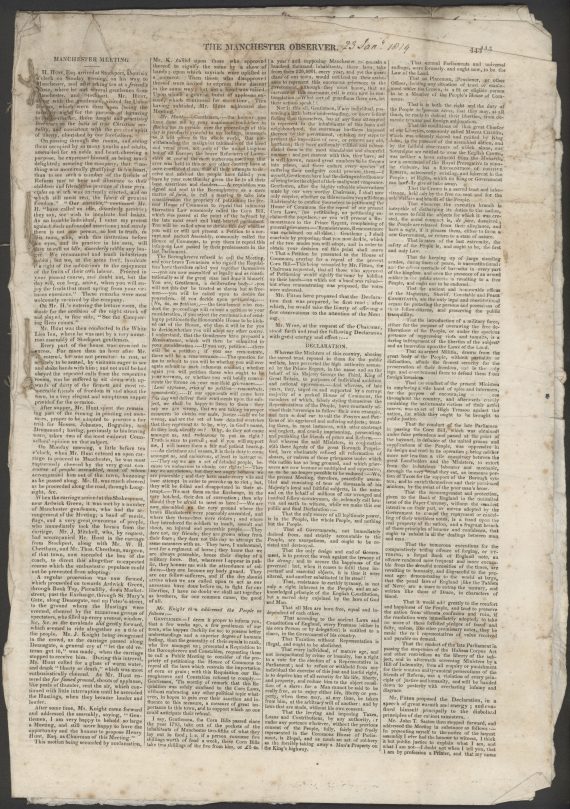

Volume 10 contains unbound pages from the Manchester Observer of 23 January 1819 which report the proceedings of a Manchester meeting organised by Henry Hunt and other reformers in 1819 to call on parliament to repeal the Corn Bill. The Corn Laws imposed restrictions and high import duties on imported grain. This kept British prices high, ensuring profit for land owners and high prices, food shortages and suffering for the rest of the population. In contrast to the current trend of short ‘soundbites,’ this in depth newspaper account details the proceedings the evening before the meeting, the meeting itself, the dinner following it and the speeches of significant speakers. We learn that Hunt took tea at a friend’s house when he arrived on Sunday evening then visited the Union Rooms, even the detail that See the Conquering Hero Comes was played when he entered the lecture room. His journeys to and from the meeting place the next day are described in great detail and the speeches on the hustings are reported in full. Hunt, in his role as presiding officer declared:

’You will be called on to decide this day whether you will or will not present a Petition to a corrupt and packed Assembly, commonly called the House of Commons, to pray them to repeal this infamous Law (the Corn Law) passed by their predecessors.’

A hostile paper describes this Anti Corn Law meeting as ‘scandalous pageantry’, and that ‘to reiterate any part of that language would be a disgrace to our columns,’ concluding with,’the whole town, the revolutionaries excepted, are disgusted with the disgraceful scenes which have been repeatedly enacted by the deceivers and deceived.’ The much smaller volume radical press was kinder, even devoted, and its publishing of reformers’ rhetoric was bold indeed.

Toasts drunk to the reforming agenda – Manchester Observer

The scrapbooks document significant national events such as the 1820 Queen Caroline affair. On his accession to the throne in 1820, George IV attempted to divorce his estranged wife, Caroline, who had returned from abroad to claim her right to become Queen. The king pressured the government to introduce a Bill of Pains and Penalties into the House of Lords, a method of using the machinery of Parliament to establish wrongs without the formal proofs essential in a court of law. If successful this would have annulled the royal marriage and deprived Caroline of her title. Perception of Caroline as a ‘wronged woman’ bravely struggling to uphold her rights against a callous political establishment made her the unlikely beneficiary of a wave of indignant public sympathy. Eventually the bill was dropped in the face of opposition from an increasing number of Whig politicians.

Open letters for and against his actions were sent to the King. An open letter from the ‘Boroughreeves and Constables of Manchester and Salford, together with the Magistrates, Clergy, Merchants, traders and Householders of those towns’ expressed their indignation and grief at the ‘shameless and unprincipled efforts of a base and seditious faction to corrupt and mislead the public mind on every essential point of morals and religion…’. In contrast a Whig – Radical meeting in Manchester sent a letter expressing loyalty to the king followed by severe criticism of his actions to Caroline, regretting that the differences between the King and Royal Consort were aired in public.

Correspondence to the papers in the scrapbooks attacks the poor as well as the reformers. ‘R’ wrote to the Sheffield Iris to put forward his plan for suppressing vagrancy – expelling people from the area and if they return subjecting them to increasingly severe flogging then eventual execution. As parish payments created idleness and profligacy, the solution to pauperism was forced labour. Letters from ‘A LOOKER ON ‘to the labouring classes of Manchester warned of the evil consequences of universal suffrage and a letter from ‘A BRITON’ to the printers of the Manchester Chronicle states that normally any respectable person wouldn’t take any notice of reform newspapers:

‘but, as they are made the most the most powerful instruments for demoralizing the poorer classes of society, by the seditious and wicked matter with which they are generally filled,in times like the present they may do much harm, and therefore require some notice.’

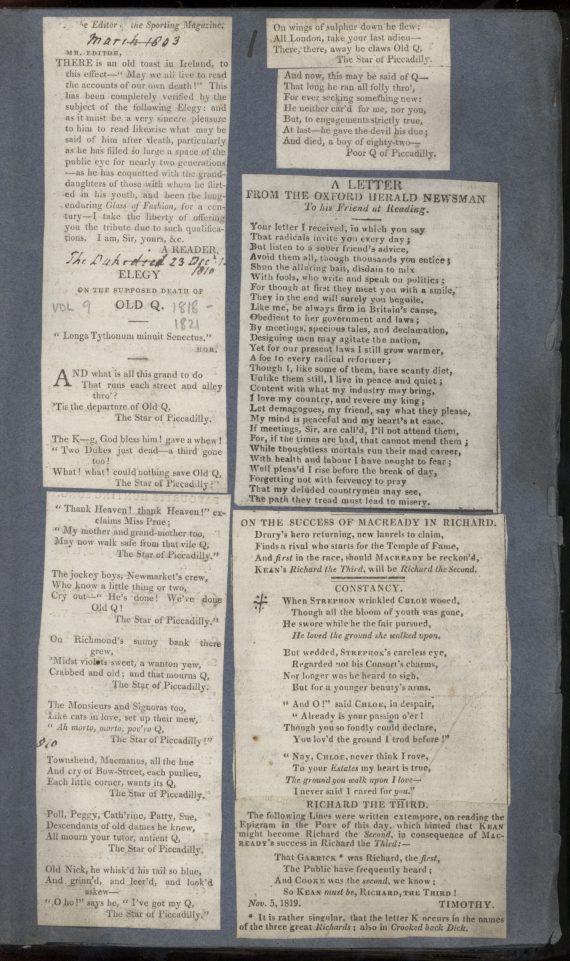

Anti-radical poems and doggerel enliven the scrapbooks.

CHARACTER OF A RADICAL REFORMER

A radical’s character’s easy to draw:-

He hates to obey – but would govern the law;

In manners unsocial, in temper unkind,

A rebel in conduct, a tyrant in mind;

Malignant, implacable, enviously sour,

He hates every man who has riches or power;

So empoison’d himself, he would gladly destroy

The comfort and blessings which others enjoy.

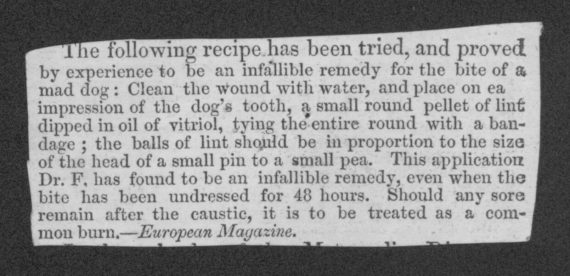

The vitriol against Henry Hunt, John Paine, and other radicals is strangely juxtaposed with love poetry, agricultural hints, humorous snippets and other ephemera, so that, for example, under Mr Hunt’s letter to the survivors of Peterloo Hay has pasted advice about how to keep frost from turnips.

An unlikely cure for rabies among the cuttings

We even see occasional glimpses of humour such as this epitaph from Dunmore church-yard:

‘Here lie the remains of JOHN HALL, grocer – This world is not worth a fig and I have good raisins for saying so.’

This perhaps gave Hay a smile as he worked himself into a rage against the radicals, a rage which produced this treasure trove of reporting on pro- and anti-radical activism.

6 Comments

Rita

Does the scrapbook say where Dunmore churchyard is ???

ferguswilde

Hi Rita! It doesn’t, I’m afraid – it’s just one of Mr Hay’s more humorous cuttings. There seems to be one in County Galway and one in Kilkenny, but I don’t immediately see one in England.

KEVIN PARSLOW

Please amend this otherwise excellent description. It was James Moorhouse of Stockport for whom a warrant was published. He was my 4 x great grandfather. He stood trial with Hunt, Bamford and 7 others in York but was acquitted.

ferguswilde

Thanks, Kevin, duly amended!

KEVIN GRAHAM PARSLOW

Hi there, don’t know if this is still monitored but I was just re-reading this and the dates for William Hay seemed odd, given that he was collecting past 1820. Wikipedia gives his dates as 1761-1839

ferguswilde

Yes, thanks Kevin, a typo indeed. Amended now!