- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

The Ancoats Brotherhood

You will do the greatest service to the state

‘If you shall raise, not the roofs of the houses, but the souls of the citizens; for it is better that great souls should dwell in small houses, rather than for mean slaves to lurk in great houses.’

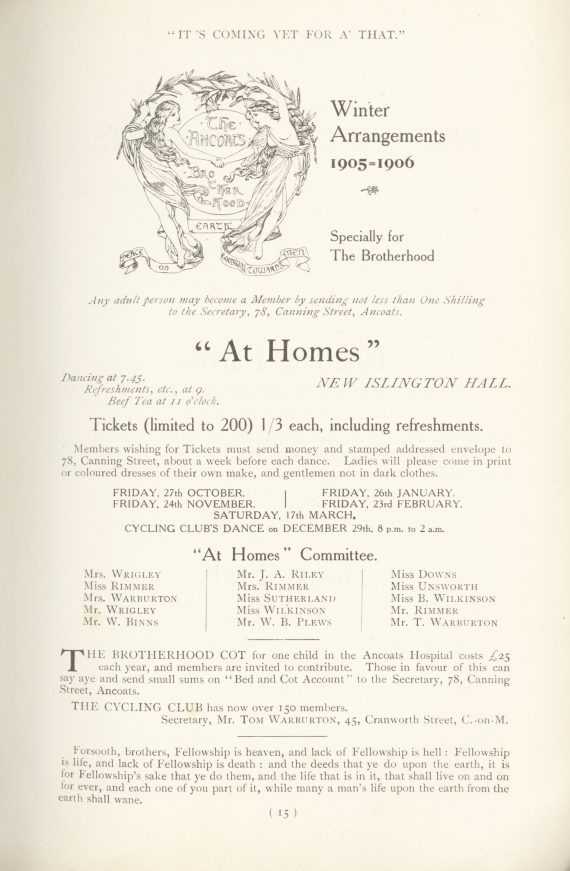

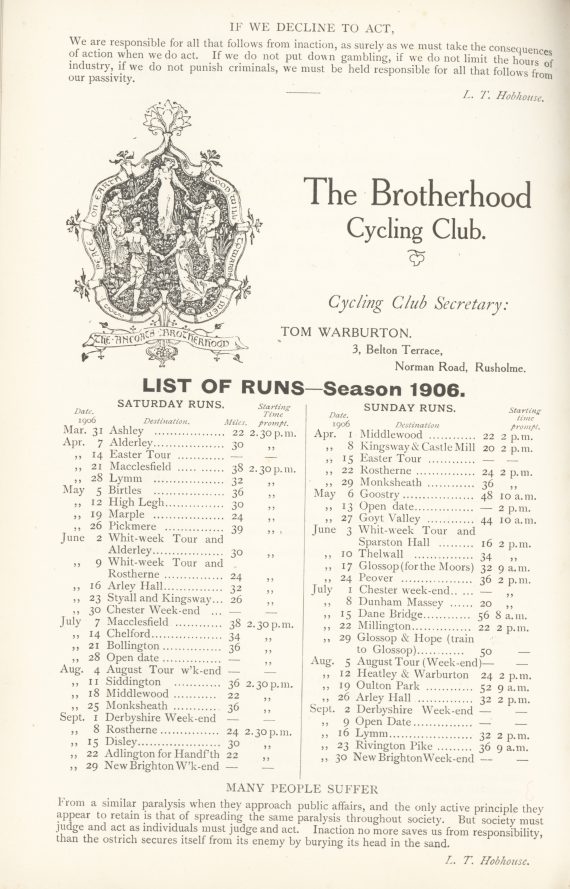

Ancoats is not a stranger to high culture. In December 2016 you could watch a performance of The Snow Queen at Hope Mill Theatre, in a renovated Ancoats cotton mill built in 1824. Our collection of the Ancoats Recreation Committee programmes (recently much expanded thanks to the vigilance of bookseller Roger Treglown) illustrates the entertainment on offer in December 1898. The workers who sweated in Hope Mill and other Ancoats mills and factories could attend lectures on Goethe, George Stephenson, Millais, The Art of Bas-Relief, Life in England 600 Years ago and Wyclif. There were weekly concerts and childrens’ entertainments, and on December 16 The Ancoats Brotherhood Cycle Club’s ‘At Home’ offered refreshments and dancing, finishing with beef tea at 11p.m. Ladies were asked to ‘please come in print or coloured dresses of their own make and gentlemen not in dark clothes’.

These activities were organised to enrich the lives of Ancoats workers who lived in wretched poverty in damp, dark, overcrowded houses. They had no running water and little natural light penetrated the foul narrow streets. Men, women and children worked long hours in uncomfortable and dangerous conditions, health was poor and a quarter of all children born in the area died young. Manchester social reformers Charles Rowley and Thomas Horsfall were shocked by these conditions and dedicated themselves to improving the workers’ lives. These men were influenced by the ideas of William Morris and the socialist artist and critic John Ruskin that arts and literature could lift the souls and spirits of working people and Rowley founded the Ancoats Brotherhood then later Horsfall established the Manchester Art Museum to put these beliefs into practice.

Charles Rowley, who was born in Ancoats in 1839 was influenced by his father who was ‘a Peterloo man, and an early pioneer in self education and the helping of others.’ Rowley describes his horror at the conditions and stench when visiting cellar dwellings in Fifty Years of Ancoats Loss and Gain, 1898, and he became driven to improve the lives of his neighbours.

Rowley become a liberal councillor for Ancoats in 1875 and campaigned for improvements in sanitation and other municipal services. He also believed passionately in the power of art and culture to alleviate the drudgery and oppression of working people’s lives and established the Ancoats Brotherhood in 1878. The Ancoats Brotherhood offered a programme of cultural activities that aimed to offer an alternative to drinking dens and musical halls to enrich the lives of working class Ancoats residents. The Brotherhood was a great success and had around 2000 paying members by the early 1900s. Members paid a subscription of 1s a year and wealthy people were encourage to contribute more, with any surplus made during the year donated to support a child’s cot in Ancoats hospital

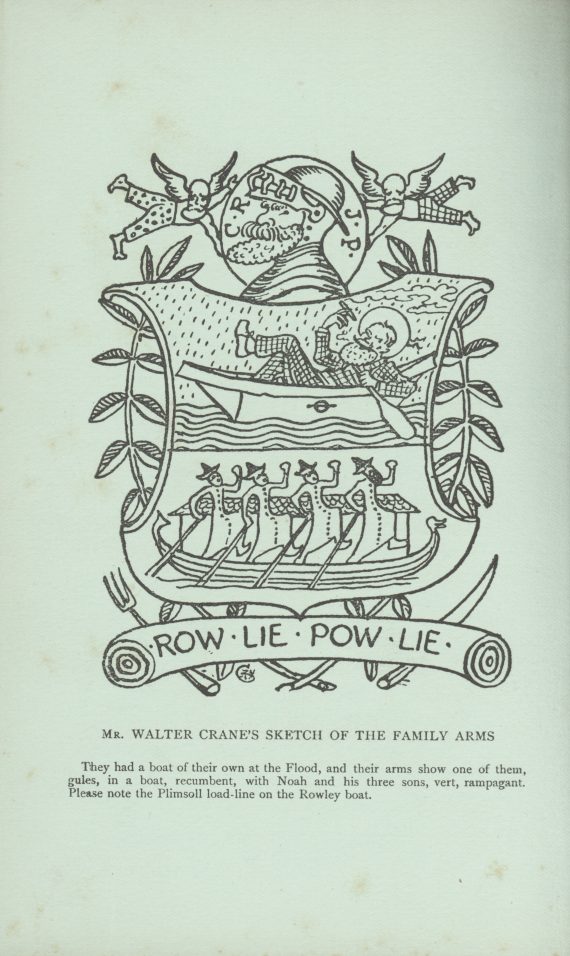

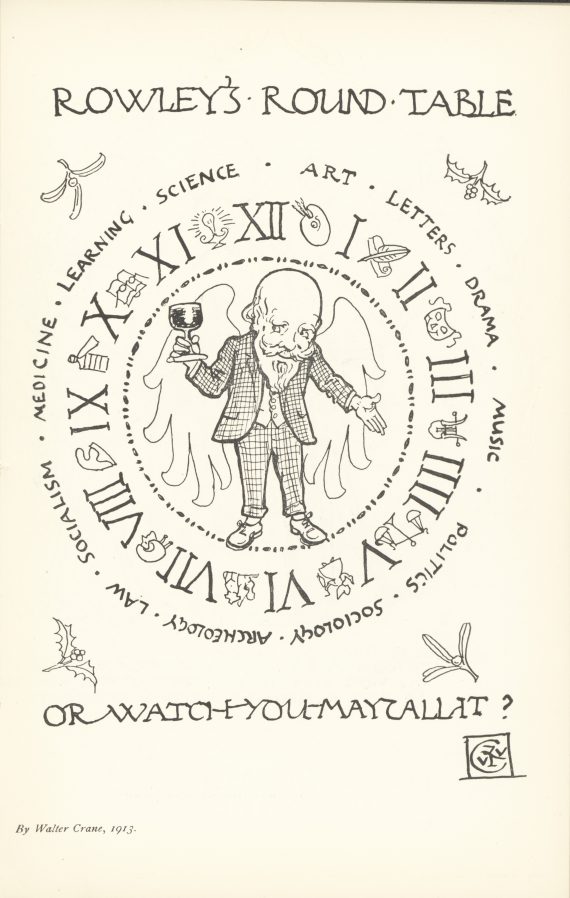

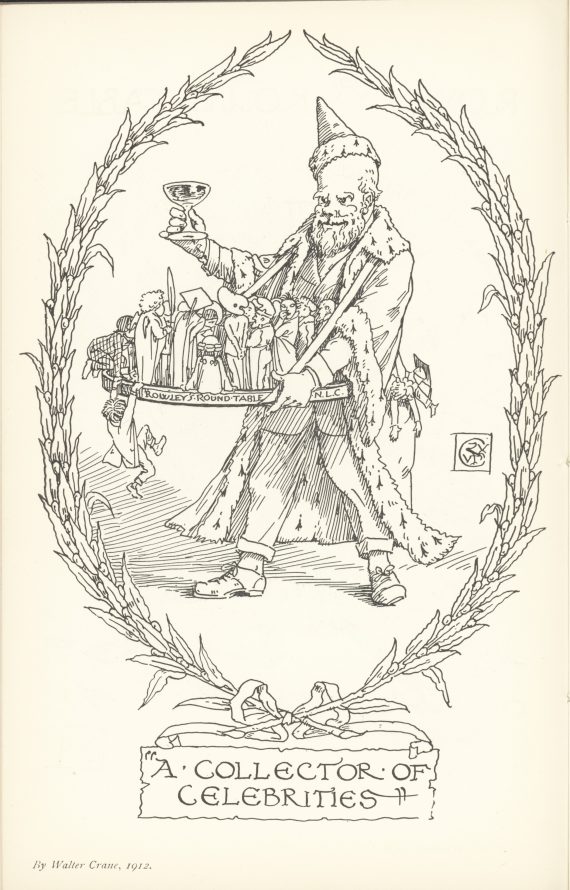

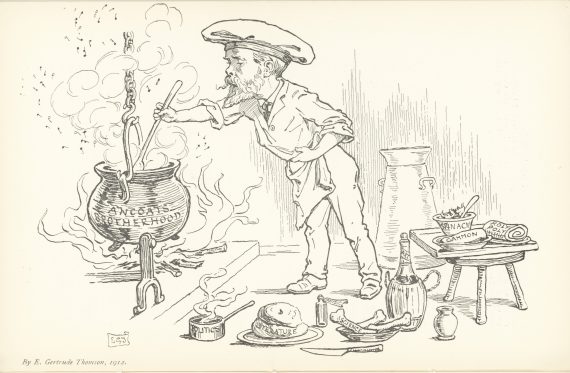

We can see the astonishing range of activities they offered in our collection of programmes. The 19th century socialist artist and illustrator Walter Crane designed the emblem and illustrated many of the Brotherhood’s leaflets and publications. Crane was a champion of workers rights and shared Rowley and Ruskin’s vision of progress through art and literature.

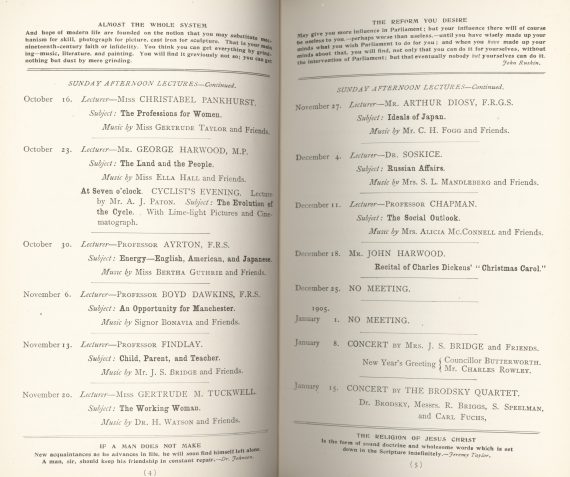

Early events included concerts and art exhibitions. After 1884 there were Sunday afternoon lectures at New Islington Hall in Ancoats. Many prominent social reformers, academics, writers and artists of the day such as Christabel Pankhurst, George Bernard Shaw, Gertrude M. Tuckwell, Edward Carpenter and G K Chesterton spoke on an eclectic mix of themes. In 1904 – 5, for example, topics included The Insanity of War, The Poetry of Robert Browning, Professions for Women, and Russian Affairs. There was music before and after the lectures. George Bernard Shaw suggests this was the only way to get people to attend, ’however good sermonising may be for people’s souls, it will bore them so fearfully that unless he begins with some good music they will not come and unless he consoles them with more afterwards they will not stay.’ From 1888 new activities included rambling and cycling clubs, holidays, dances, and reading groups led by radicals such as Eva Gore Booth. The programme were also designed to educate. They printed political or uplifting quotations at the head and feet of pages, published the words of songs to be performed and often longer articles such as Lincoln’s 1863 Gettysburg address, printed in 1909. Works by artists such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti and E. Burne Jones were reproduced.

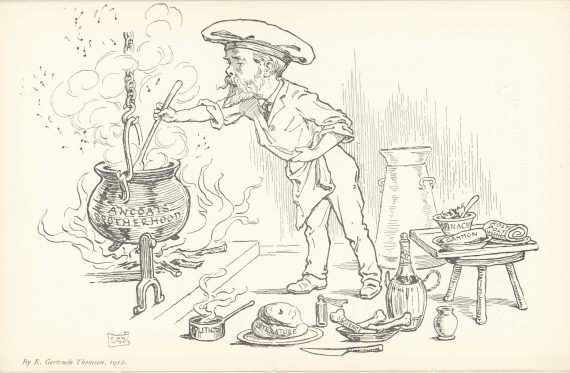

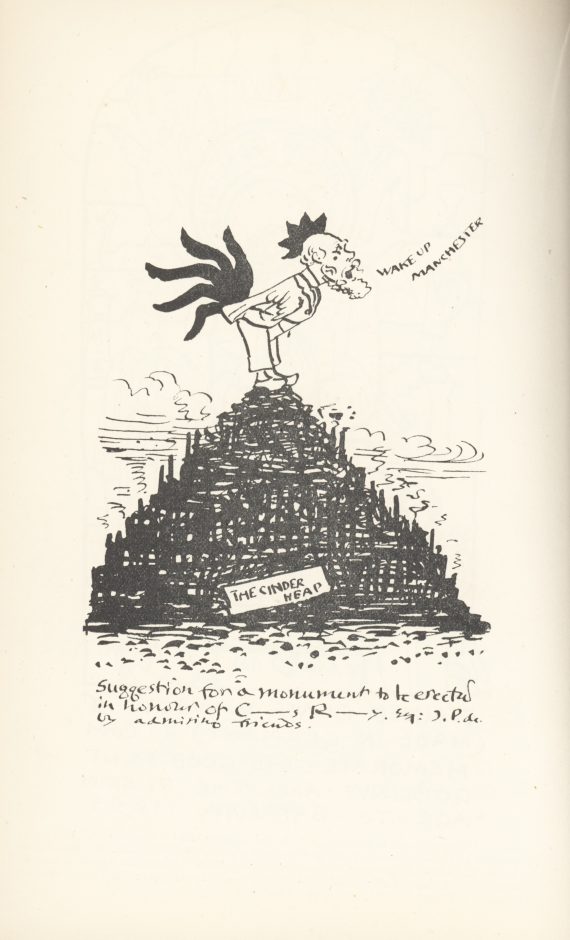

Crane and other friends that Rowley called in to support the brotherhood indulged in good natured caricature of his single-mindedness and ability to persuade them to contribute. Sylvia Pankhurst recalls that some Sundays they went to the Ancoats Brotherhood ‘who brought to that factory blighted district examples of the best things of the time in music, art and science. His rotund little figure, with its bald head, long red beard and smooth twinkling eyes, under most bushy and aggressive eyebrows was pictured by Walter Crane in many a humorous guise as “Saint Rowley-Poly.”

George Bernard Shaw wrote about Rowley’s ability to persuade people in his huge network of contacts to contribute to Brotherhood events. ”No matter what spot of the globe you may happen to be, you are never safe from a summons to come to Ancoats and speak for the Brotherhood, or sing for the Brotherhood, or fiddle for the Brotherhood or do something else equally exhausting and distressing for the Brotherhood,’ and ‘Rowley is the only man alive who could induce any sane man to go to Manchester unless he had urgent and lucrative business there, and he abuses his powers mercilessly.’

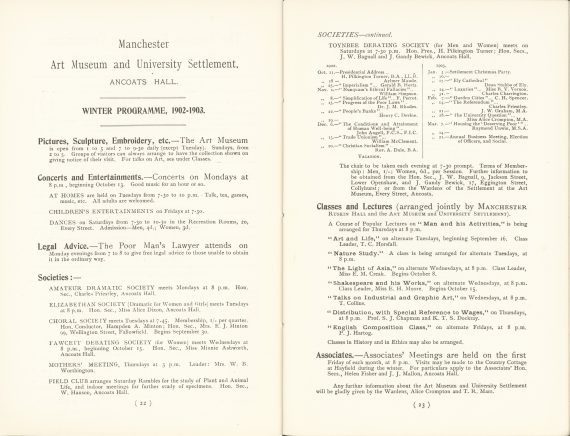

The Manchester Art Museum and University Settlement

The Ancoats Recreation programmes also detail the activities offered by the Art Museum and University Settlement. The Arts museum was founded by Thomas Horsfall another Manchester philanthropist who was influenced by Ruskin to aspire to bring light to the working people through the arts. His museum was dedicated to working people and children. The Art Museum contained painting, sculpture, architecture and crafts. He also created a picture collection to loan to schools. The Art Museum also offered craft classes, nature study groups, concerts, lectures and readings.

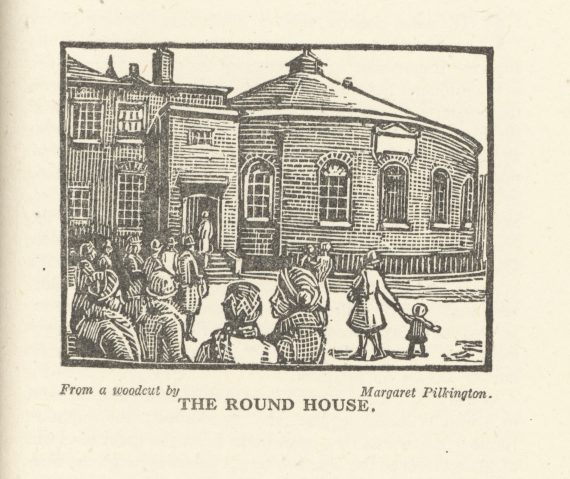

The Manchester Settlement was another organisation established to support the poor of Ancoats. It was founded in 1895 by the University of Manchester and initially shared premises with the Art Museum. In 1926 a bequest made possible the purchase and reconstruction of the Roundhouse in Every Street. Sadly this building is no longer standing although the Settlement survives today and still offers programmes in Openshaw that reflect the aims and ambitions of the original settlement.

The library has a copy of Fifty Years in Every Street by M.D. Stocks, 1945. This volume charts the the history of the first 50 years of the settlement which was modelled on Toynbee Hall, where paid wardens and university students lived amongst poor communities to help remove some of the inequalities of life, research social conditions, carry out educational experiments and train social workers. Early workers included prominent women’s suffrage campaigners such as Christabel Pankhurst and Eva Gore Booth, Ellen Wilkinson and Margaret Ashton. It was a meeting place ‘for all classes in a common fellowship,’ a hub for neighbourhood social life, gave advice and help to people in need and liaison between officialdom and ordinary citizens.

Activities included lectures, classes and discussions addressing a range of topics to expand the knowledge and interests of residents. At one stage a Miss Creak taught the history of art to elementary school children and expounded topics such as Mazzini, St Francis of Assissi, the wonders of the sea and Sophocles with a group of adults.There were many clubs and social activities including the field club, the disabled folks guild programme of socials, choirs, girls clubs, choirs, girls clubs, the Saturday dance evening. Tuesday ‘at homes’ started as small gatherings of residents meeting talk ‘diversified with music or recitation then attendance grew to hundred, but the informality of the gatherings was retained and they persisted for many years.

Poverty was always present and did interrupt attendance. The annual report for 1922 – 3 describes adult education classes in which numbers have suffered because ‘When men have no decent boots or clothes, or when they cannot pay the usual small fee as others do, they stay away.’

These organisations persisted in Ancoats well into the twentieth century. Eventually the mills and factories closed, the people left and the buildings were left empty. Regeneration is again using art and culture to help bring the area back to life.

2 Comments

Matthew Cobb

Some of the Sunday lectures given by Arthur Milnes Marshall, Professor of Zoology at Owens College, and then the Victoria University, in the late 1880s/early 1890s are being reprinted this year, thanks to the work of Professor Martin Luck of the University of Nottingham. Marshall gave a lecture on Butterflies on 12 January 1890, and another on Animal Pedigrees on 6 December 1891. It would be marvellous if you had a copy of the programmes and could reproduce them – I am sure that Professor Luck would be keen to provide you with some context to show the significance of these events.

Mr Barry Anderton

Let us hope that the trust placed in education was not misplaced! A truly great movement that will hopefully survive television and mass media.