- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Thomas Jones: Chetham’s Greatest Librarian

As we continue our journey through the lives of Chetham’s Librarians, one name stands out above all others: that of Thomas Jones, a man with a reasonable claim to the title of ‘Chetham’s greatest librarian’. Born in Margam, Glamorgan in 1810, Jones received his early education at Cowbridge Grammar School; this was one of Wales’ most famous schools, and also a feeder school for Jesus College, Oxford. Unsurprisingly, Jones subsequently attended the college, where he received his bachelor’s degree in 1832. Although he had originally planned to take holy orders after his studies, Jones instead decided to pursue a career in the world of books; in 1842, he compiled a catalogue of Neath Library in Wales, and in March 1845 he was appointed as Chetham’s Librarian following the death of the former librarian, the Reverend Campbell Grey Hulton. Jones was to serve as Chetham’s Librarian until his death in 1875, making him one of the library’s longest-serving librarians – surpassed only by Robert Thyer before him, and Michael Powell after him.

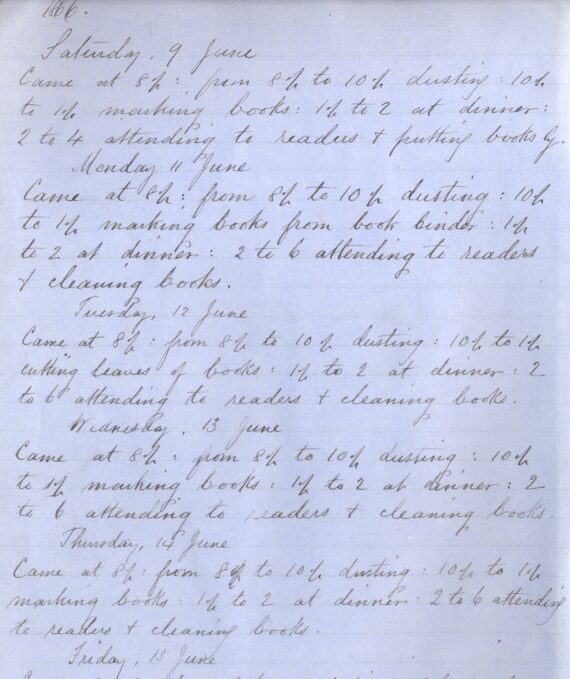

The librarianship proved to be a role that Jones was particularly well-suited to. The Manchester bibliophile James Crossley – a founder of the Chetham Society (an antiquarian society dedicated to the study of Lancashire and Cheshire history) and its president from 1847-83 – characterised Jones as ‘one who was seemingly designed by nature for the place and whose whole soul was in his work’, while Jones’ obituary described the library as ‘the sphere for which he was excellently adapted’. Diaries kept by Jones reveal the consistency with which he carried out his responsibilities: most days began with dusting and cataloguing (perennial tasks in a library like Chetham’s), and in the afternoons he attended to readers. During his librarianship, Jones was also responsible for more than doubling the library’s holdings, which increased from 18,000 to 38,000 volumes. This was often achieved through Jones’ personal intercession, and the accessions register from this time records books entering the collection through ‘the librarian’. Crossley too played an important role in this expansion, acquiring books for the library, and the two men formed a close working relationship. Later, Crossley would become an honorary librarian after Jones’ death.

Fig. 1: Thomas Jones’ diary from 1866.

In addition to increasing the library’s holdings, Jones took great pains to ensure that they were accessible to those who wished to use them. He compiled a Catalogue of the collection of tracts for and against popery (published in and about the reign of James II) in the Manchester library founded by Humphrey Chetham, which was published by the Chetham Society in 1859. Then, he prepared two volumes of catalogues of the library’s general holdings: first, a continuation of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century catalogues produced by Chetham’s Librarians John Radcliffe and William Greswell, which was published in 1862, and then an alphabetical catalogue published the following year. Lastly, he began work on a biography of John Dee (warden of Manchester’s collegiate church from 1596-1608/9) and an edition of some of his letters, under the title A selection of the letters written by Dr Dee with an introduction of collectanea relating to his life and works. This work was still incomplete upon his death and was never published, but Jones’ manuscript copy of it is preserved in our collections, written on the blue paper that he preferred to use.

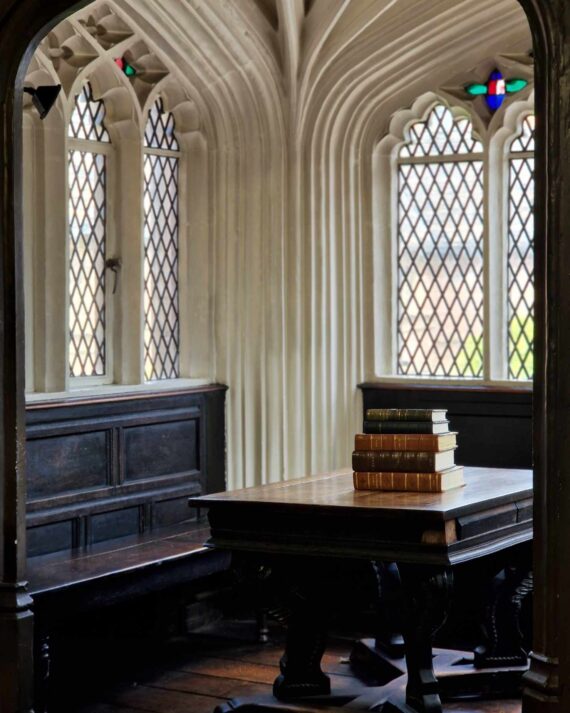

Fig. 2: The alcove where Marx and Engels studied in the summer of 1845.

During Jones’ librarianship, use of the library flourished, and it was soon after he took up the post, in the summer of 1845, that the library received two of its most famous visitors: Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. At the time, Engels lived in Manchester and was employed by his father’s firm, which manufactured cotton thread, while Marx lived in London and frequently travelled to Manchester. The two men spent six weeks that summer studying together in an alcove in the Reading Room, a period of intellectual activity that ultimately led to the publication of the Communist Manifesto in 1848. The original books that they consulted are still held by the library, and can be seen on the shelves by the landing; meanwhile, facsimiles are kept in the alcove where they studied for visitors to peruse. When Marx and Engels visited, it is likely that Jones located these books and brought them to the Reading Room, and they undoubtedly benefited from Jones’ extensive knowledge of the collections which led to his description, in his obituary, as the library’s ‘living index’.

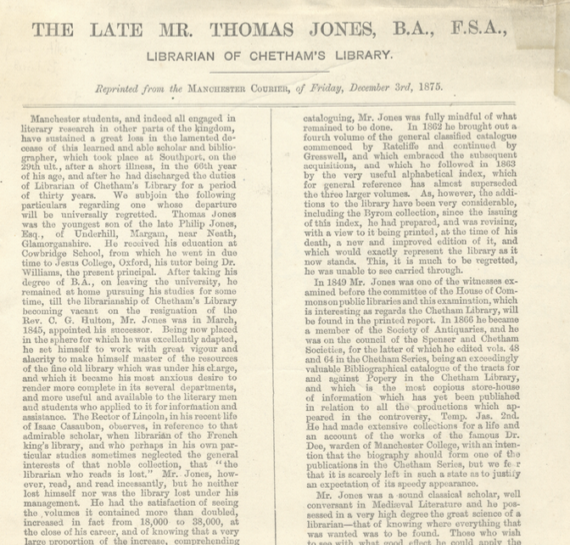

Fig. 3: Obituary of the late Mr Thomas Jones, B.A, F.SA., Librarian of Chetham’s Library, 1875.

Nevertheless, in his old age, Jones struggled to discharge his duties as librarian. Writing to Marx in 1870 after another visit to Chetham’s Library, Engels remarked that ‘during the last few days I have again spent a good deal of time sitting at the four-sided desk in the alcove where we sat together twenty-four years ago. I am very fond of the place. The stained-glass window ensures that the weather is always fine there. Old Jones, the Librarian, is still alive but he is old and no longer active. I have not seen him on this occasion. Despite his infirmity, Jones would continue as the librarian for another five years until his death, following a short illness, on 29 November 1875. His successor and friend Crossley lamented that ‘I seem to have lost half of myself…I am too much affected to say more.’ He was buried at St Mark’s Church in Cheetham Hill, only a stone’s throw away from where he had spent the majority of his life, and where his dedication to the books and cultivation of the collection undoubtedly shaped Chetham’s Library into what it is today.

By Megan Devereux and Emma Nelson.