- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Contingency Planning and the Wartime Library

On Friday 4 November 1938, the Library Committee of Chetham’s Library assembled—perhaps in the library’s Reading Room—as Chetham’s Librarian prepared to address them. The weather in Manchester that day was mild and slightly rainy, but across Europe, storm clouds were gathering. During the 1920s and 30s, a rising tide of fascism had engulfed Italy, Spain and Germany as three dictators—Benito Mussolini, Francisco Franco and Adolf Hitler—came to power in their respective countries. Allied appeasement of their regimes in the 1930s masked British re-armament, and by the end of the decade, there was a growing sense that matters were coming to a head. In October 1938, as another war seemed inevitable, the British Government sent out notices to the country’s major cultural institutions, instructing them to develop plans to be followed in the event of hostilities breaking out.

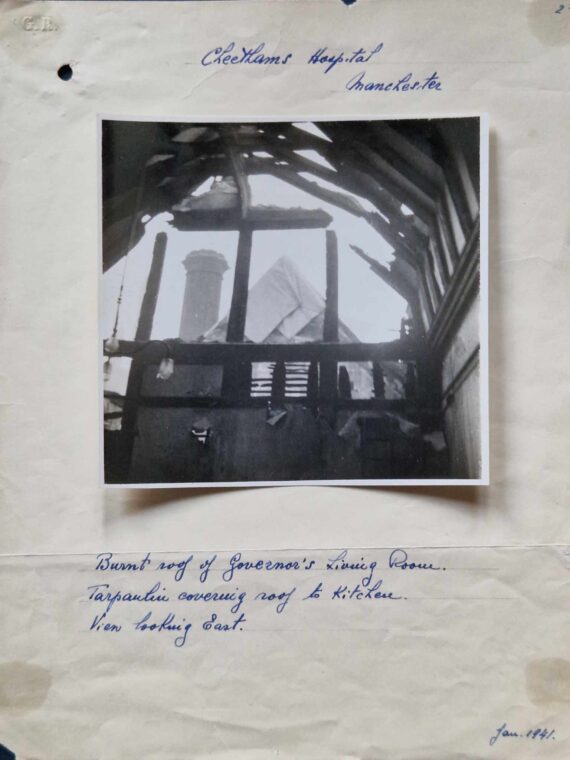

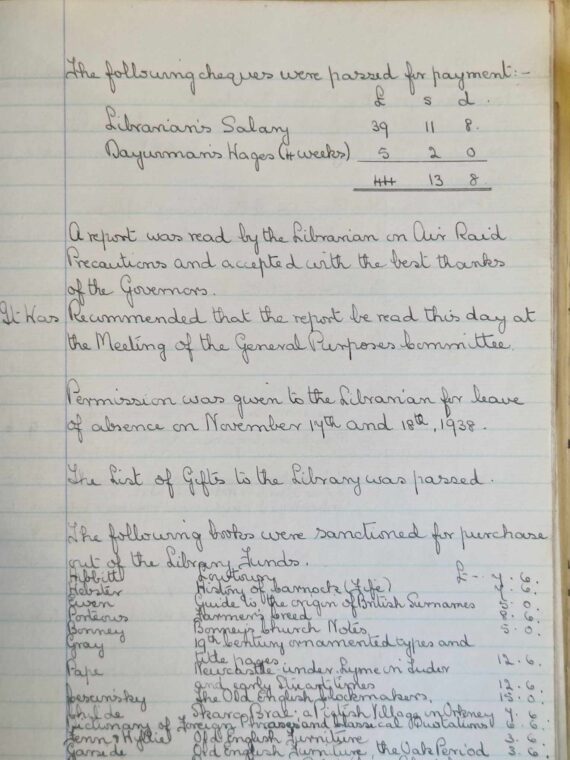

Figure 1: The minute-book of the Library Committee, open on the entry for 4 November 1938 (Chetham’s Library, C/Lib/Min/3).

Chetham’s Library was one such institution, and its librarian, Charles Phillips, had received this notice on 7 October 1938. Since his appointment in 1920, Phillips had spent almost twenty years immersed in the day-to-day work of the library, which consisted largely of cataloguing and indexing various collections of deeds and paintings. He had also taught classes in bibliography at the University of Manchester, delivered lectures on a wide range of themes to local societies, and contributed to radio broadcasts (the drafts of these lectures survive in the Phillips Collection in Chetham’s Library). The beginning of Phillips’ librarianship was therefore relatively peaceful, but it would be a mistake to assume that he was consequently ill-suited to running a wartime library; when the notice to prepare for hostilities arrived on Phillips’ desk, he immediately sprang into action, writing to other libraries to ask about their plans

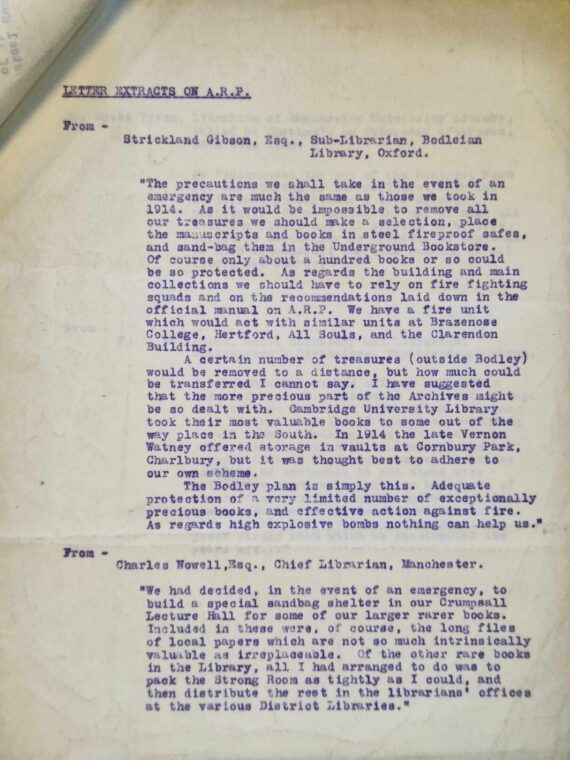

The first of his correspondents was Strickland Gibson, Sub-Librarian at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, with whom Phillips perhaps had a prior acquaintance. Gibson had been a Library Assistant at the Bodleian between 1895 and 1912, and Phillips was appointed an Under-Assistant there in 1899, before joining the Extra Staff in 1903; it seems likely that the two men met around that time and continued their acquaintance, since the Phillips Collection contains, in addition to the drafts of Phillips’ lectures, an offprint of a lecture entitled ‘The Keepers of the Archives of the University of Oxford’, delivered by Gibson on 7 March 1928. The next two correspondents were far more local. One was Charles Nowell, who, after a career in various libraries, assumed the role of Chief Librarian at Manchester Central Library in 1932. The other was Dr Moses Tyson, who was Keeper of Western Manuscripts at the John Rylands Library from 1927 until his appointment as Librarian at the University of Manchester in 1935. Phillips was presumably well-acquainted with Tyson, given his lectures in bibliography at the university, and unlike the other librarians consulted, Tyson called on Phillips at Chetham’s Library in person. Phillips’ final correspondent was Frederick Wellstood, Librarian at Shakespeare’s birthplace in Stratford-upon-Avon, and the exact nature of the relationship between these two men—easily the most unexpected of the four—is not yet known.

Figure 2: Typed extracts from a letter from Strictland Gibson, Bodleian sub-librarian (Chetham’s Library, C/Lib/Misc/28).

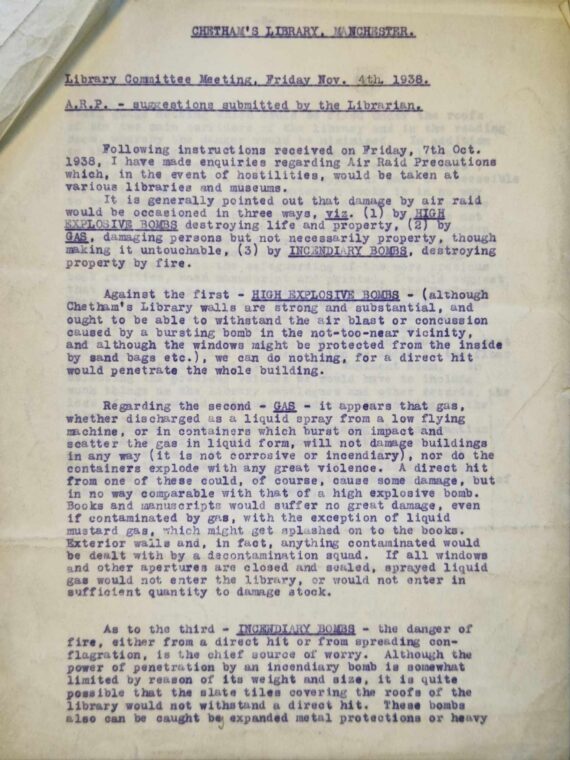

Based on these librarians’ responses, Phillips formulated his recommendations for the library’s wartime precautions, noting that ‘damage by air raid would be occasioned in three ways’. The first threat was that posed by high-explosive bombs. Phillips expressed the hope that the thick walls of the medieval college buildings would be able to withstand the blast of nearby bombs, while sandbags might protect the fragile windows. He nevertheless noted that a direct hit would penetrate the building, echoing a general consensus summed up by Gibson’s sobering statement: ‘as regards high explosive bombs, nothing can help us’. The second danger was gas, which Phillips noted was more hazardous to the library’s staff than to the building or collections, since it was neither corrosive nor incendiary. He therefore suggested closing and sealing the library’s windows to prevent gas from entering the library; in the event, the library’s windows were boarded up, preventing their breaking and the entrance of gas at the same time. The final threat was that of fire spreading from incendiary bombs. Phillips noted that, while the force of an incendiary bomb was minimal, one might still penetrate the medieval slate tiles of the library’s roof. To reduce the damage that this would cause, he proposed the installation of a steel net above the library’s corridors to catch the bombs, an approach suggested by Wellstood. He also recommended the placement of buckets of sand in the library, in addition to the firefighting equipment usually kept there, since tightly-packed books do not burn quickly and the use of water on them was ‘in no way to be recommended’. At the same time, he noted the inevitable risk that fire posed to the wooden presses, floors and roof beams.

Figure 3: Phillips’ suggestions to the Library Committee (Chetham’s Library, C/Lib/Misc/28).

Finally, Phillips advanced some suggestions for the safeguarding of the collections. He proposed that the ‘more precious book rarities, both manuscript and printed’, together with the catalogues and records of the library essential to its daily running, could be moved to the Muniment Room. This was ‘the Bodley plan’ that Gibson had outlined in his letter (‘adequate protection of a very limited number of exceptionally precious books’ in the Underground Bookstore, now the Gladstone Link), while the use of the Muniment Room had been recommended Nowell during his visit: it was practically fireproof, had thick walls and a paved floor, and only a small window. Phillips suggested covering this window, and the floor above this room, with sandbags. There is no echo in Phillips’ proposals of the recommendations by Gibson and Nowell concerning the removal of the rest of the collection to other sites, but in the event, some of the library’s books were sent to the Central Library, some of its furniture to Tatton Park, and sixteen paintings (including that of Humphrey Chetham) to the basement of the Whitworth Art Gallery.

On 3 September 1939, Britain declared war on Germany. The following day, the library closed to visitors and readers, but re-opened to readers following a meeting of the Library Committee on 13 October. The library continued to operate in this limited capacity for most of the war, and its business largely carried on as usual: readers consulted the collections, new books were purchased, and discussions were held around the library’s acquisition of the Gorton Chest (a plan that would not be realised until the chest’s permanent loan to the library in 1984, and its eventual purchase in 2001). The spectre of war was ever-present, however, and the validity of Phillips’ concerns were proven by the devastating ‘Christmas Blitz’ of December 1940, in which Manchester Cathedral was badly damaged by a direct hit, and the library suffered some damage. It was reported on the radio and in the news that the library had been destroyed, and Luxmoore Newcombe, the Librarian at the National Central Library, wrote to Phillips to offer whatever assistance he could supply. A few days later, Phillips replied that the damage was ‘not nearly as bad as one would imagine’, and that ‘the House-Governor’s quarters are totally destroyed by fire; one dormitory is burnt out; but my Library is intact’. In another letter, he related that ‘all the windows were shattered, the panelling blown away from the walls, the roof broken in a number of places, books hurled from their shelves, a good deal of damage from water and dirt, [and] fifty volumes spoiled in their bindings’, but that no pages had been lost, and that none of the collections stored in the Muniment Room were damaged in any way. The good sense of Phillips’ precautions had been proven.

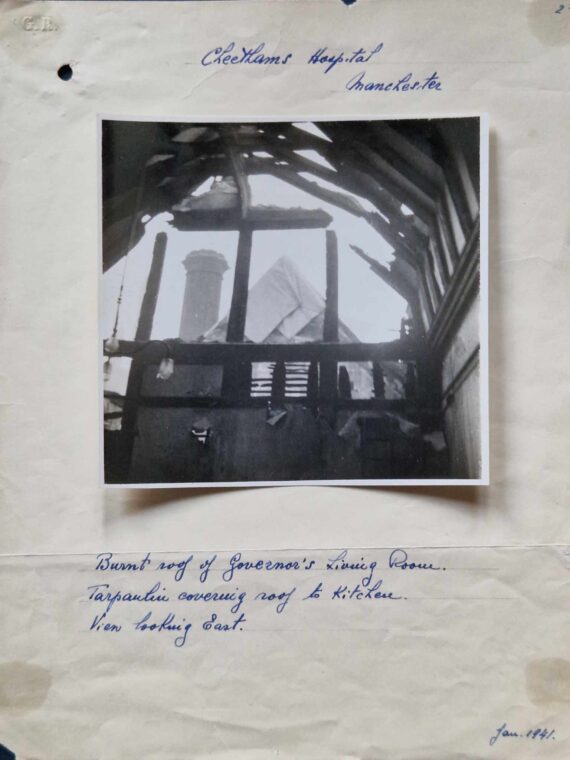

Figure 4: Damage to the library’s roof as a result of bombing during the ‘Christmas Blitz’ (Chetham’s Library, no shelfmark).

In July 1943, the library closed again, this time following Phillips’ death. The Library Committee decided that no action would be taken to appoint a new librarian until after the war, and in the meantime, they turned to Nowell for guidance. Following an inspection of the library, Nowell made several suggestions to the Library Committee on 30 September. One of these was the installation of a sign outside the library, advising that the library was now closed and directing would-be readers to apply to Nowell at the Central Library. Another was a thorough regime of book-cleaning, since the collections had gathered dust during the war, and Nowell loaned some of the staff from Central Library to assist with this. The task of cleaning continued well into the late 1940s, following the appointment of Hilda Lofthouse as Chetham’s Librarian. Hilda’s time as librarian was no less interesting than Phillips’, and the curious reader can discover more about her in an upcoming blog post; this post celebrates the librarian who took steps to protect our library during one of its greatest moments of crisis.

Blog post by Emma Nelson