- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

The Manchester Woman: Mrs Isabella Linnæus Banks

One member of the Sun Inn Group of poets who met at Poets’ Corner, who is now among the most famous but was little-known at the time, was Mrs Isabella Banks (née Varley). One of nineteenth-century Manchester’s most prolific authors, she published no fewer than twelve novels, three volumes of poetry and three volumes of short stories between 1865 and 1894, but she also lived a life that could itself have provided the narrative for a Victorian novel. Her friend, the social reformer and writer Florence Fenwick Miller, wrote of Isabella that her literary productivity (of novels rather than poetry) was necessitated by her need to provide an income for her family: ‘not till she was forty three did Mrs Banks resume her pen … it was rather that circumstances compelled her to find food and education for her brood than because she desired literary position’. She had married for love in 1846, but her husband—a newspaper editor—moved the family around the country from Harrogate to Birmingham, Dublin, Durham, Sussex and Windsor, as he struggled with drink and depression until his death in 1881.

Isabella was born in 1821 and grew up in the Cheetham area of Manchester. Her mother’s family were manufacturers of ‘smallware’, what we might refer to now as ‘haberdashery’, while her father was originally a chemist; after his eyesight was damaged in an accident, however, he and his wife opened a haberdashery shop from their home. Isabella was educated locally, and she and her siblings seem to have had a happy childhood. Her parents had a wide social circle, took her to the theatre and encouraged her to join the local Mechanics Institute, where she attended talks and exhibitions and made full use of the library. Her eldest brother was a member of the Manchester Athenaeum, and through him she was present at the Free Trade Hall when Charles Dickens visited Manchester in 1857.

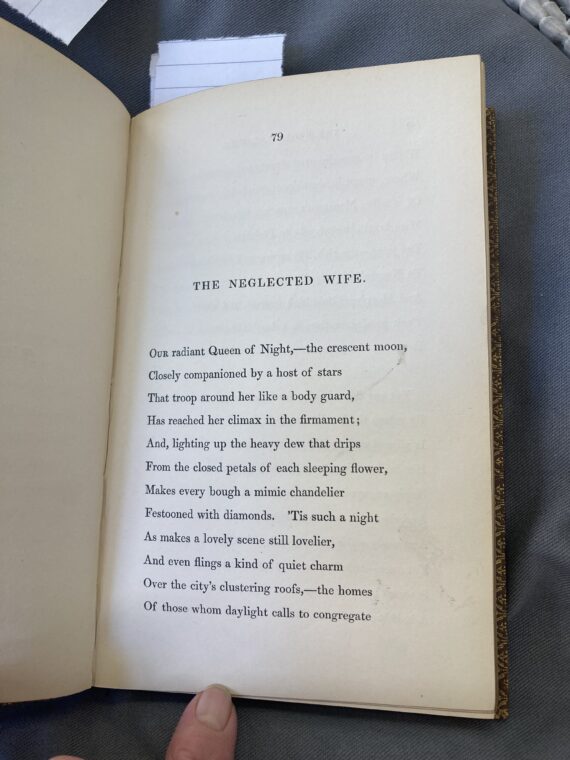

Figure 1: Isabella Varley, ‘The Neglected Wife’, in Ivy leaves (Manchester, 1844) (Manchester Central Library, 821.89B30, p. 79).

As a young woman, Isabella took a keen interest in poetry; her first published work was a poem entitled ‘A Dying Girl to her Mother’, which appeared in the Manchester Guardian on 12 April 1837, when she was only 16 years old. The following year, she began to manage a small school near her home. In 1842 she became a member of the ladies committee of the Anti-Corn Law League, and she was also a lifelong advocate for women’s suffrage. In the same year, a friend of the family, John Bolton Rogerson, became the editor of the Oddfellows Magazine. He published another of Isabella’s poems, entitled ‘The Neglected Wife’ (figure 1), which was awarded the third prize in the magazine’s annual literary competition. It is impossible to read this poem now without feeling that it foreshadows the situation which Isabella eventually found herself in following her marriage to George Linnæus Banks:

“Her husband is a truant from his home,

Haply engaged in noisy revelry,

And she with uncomplaining, patient love,

Anxiously waits his long-delayed return.

Yet once, and that so short a time agone

It seems but yesterday-her slightest word,

A half-breathed wish, had brought him to her side,

And he would linger there as if entranced”

John Rogerson was also a founding member of the Sun Inn Group, and he persuaded Isabella to become involved with the group. As the late Chetham’s Librarian Michael Powell wrote in 2017, however, ‘the young Isabella Varley attended the March 1842 soirée at the Sun Inn but lacked the confidence to perform alongside her fellow, mostly male poets and listened to their readings whilst hiding behind velvet curtains’. The songs and poems presented at the March 1842 meeting were subsequently collected together in an anthology, published in July that year as The Festive Wreath: A Collection of Original Contributions Read at a Literary Meeting, Held in Manchester, March 24th, 1842, at the Sun Inn, Long Millgate. Isabella’s poem ‘Love’s Faith’ was included in the anthology. In 1844, when Isabella was in her early twenties, a book of her poetry entitled Ivy Leaves was published by Simpkin, Marshall & Co. of London. How this publication was funded is unclear, although it seems highly unlikely that her family were the source. A significant proportion of the poems in the book are about death and dying: they include ‘The White World’, ‘The Spirit Visitants’, ‘The Funeral Bell’ and ‘Homeward Bound’ (a poem about a dying sailor). This book also re-published ‘The Neglected Wife’.

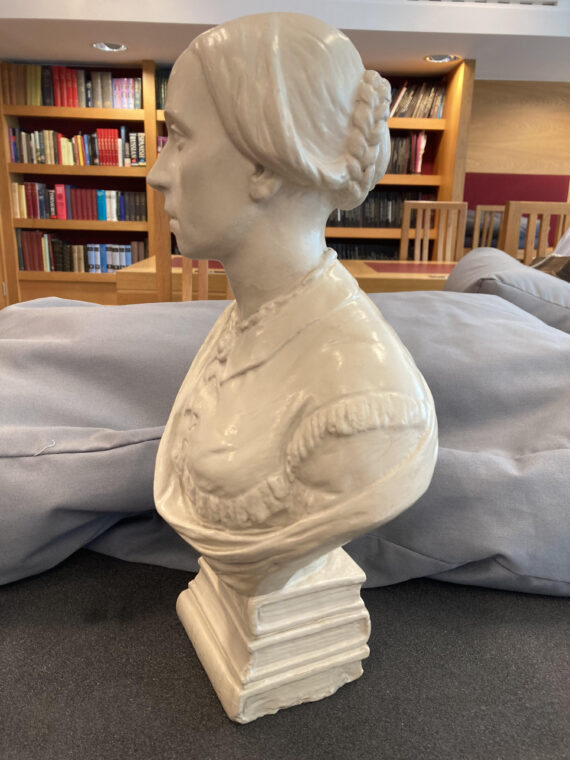

Figure 2: A bust of a young Isabella Varley (John Rylands Library, VFA.40).

It seems likely that Isabella first met her future husband, George Linnæus Banks, through Rogerson. George—always referred to by Isabella as Linnæus—was a newspaper man, writer and poet, and an active radical and public speaker. Isabella’s biographer E. L. Burney quotes ‘the writer in Manchester Faces and Places’ who stated that ‘“a young Birmingham poet had been attracted by Miss Varley’s poems in the Oddfellows Magazine, and she on her part had not been so much attracted as amused by a review in the same publication of a volume of his, Nlossoms of Poetry. Later on these two young litterateurs were introduced in a somewhat singular manner”’. They married in 1846 at Manchester’s collegiate church—now the cathedral—when Isabella was 25 years old. The E. L. Burney Collection at the John Rylands library, which contains letters, notebooks and other objects associated with Isabella Banks, contains a small plaster bust of Isabella (figure 2); there is no information about the bust’s provenance or maker, but it seems to depict her at roughly this date. The sculptor seems to suggest a sadness in his sitter.

Linnæus struggled with alcoholism and depression throughout their life together, which appears to be the reason why they frequently moved from one end of the country to the other; he went from the Harrogate Advertiser to the Birmingham Mercury, and then to The Dublin Daily Express, the Durham Chronicle, the Sussex Mercury and the Windsor Royal Standard. On more than one occasion, he sold the family’s furniture and belongings to fund his addiction, and it was a need for money that prompted Isabella to start writing fiction to support her family. Her first novel, God’s Providence House, was published in 1865, along with Daisies in the grass: a collection of songs and poems, by Mr. and Mrs. G. Linnæus Banks. also appeared. The copy of these poems in the library’s collections features a handwritten dedication by Isabella. She wrote at least a dozen more novels, some of which first appeared in instalments in magazines, but the family were still struggling financially. Her final volume of poetry, Ripples and breakers, was published in 1878; it is often biographical in nature, and Burney suggested that it ‘describes her struggles to keep her house and home together’.

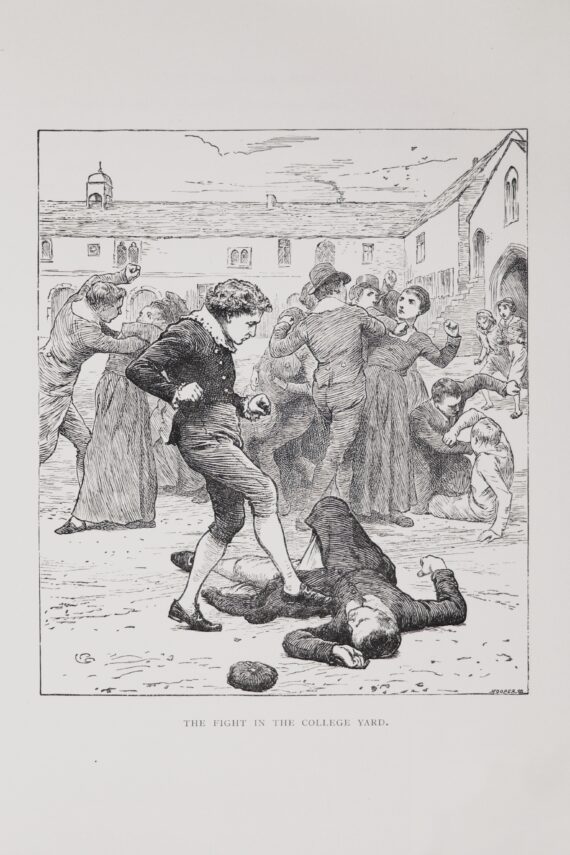

Figure 3: A fight in the yard of Chetham’s Hospital School (Chetham’s Library, 12.F.3.21, np).

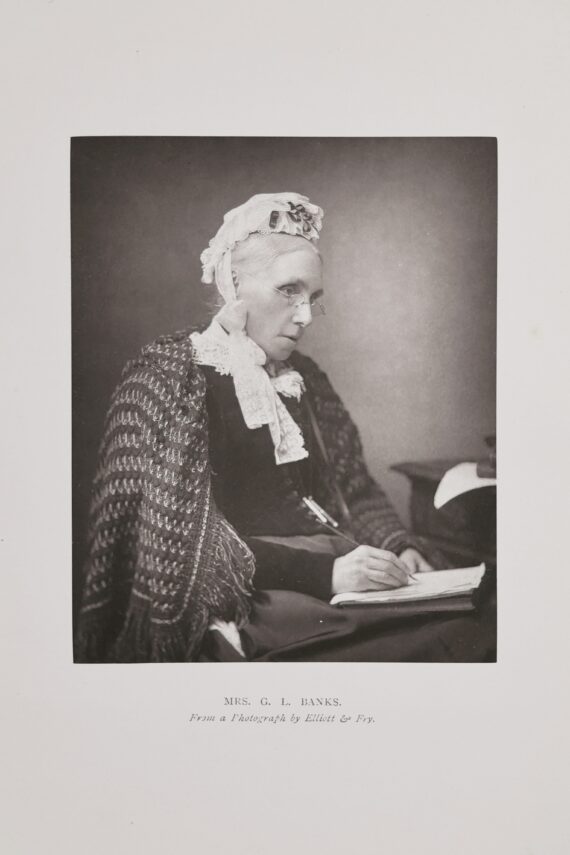

Isabella’s most famous novel was of course The Manchester Man (1876). The novel traces the life of a Manchester resident, Jabez Clegg, who was saved from drowning in a flood and educated at Chetham’s Hospital School (figure 3). The dramatic illustration above—which depicts a fight between schoolboys in the yard of the school, with what is now Chetham’s Library clearly visible in the background—is found in the 1896 edition of the novel. According to Burney, Isabella arranged to visit Chetham’s Hospital School and Library in 1866 when she first started researching her story, and she donated her manuscript copy of the novel to the library in 1887. The library still has this copy as well as sixteen printed editions of the work, including several copies of the popular 1896 edition, published by Abel Heywood and illustrated by Charles Green and Hedley Fitton. One of these includes a frontispiece photograph of Mrs Banks (figure 4). The image is striking, but perhaps not flattering; it depicts her at around 76 years old as a bespectacled old lady.

Figure 4: Photograph of Isabella Banks (Chetham’s Library, 12.F.3.21, np).

Isabella also applied for—and received—several grants from the Royal Literary Fund. In an article on female applicants to this fund published in 1990, S. J. Mumm described how ‘Isabella Banks, best known as the author of The Manchester Man, had ten children to provide for as well as supporting an alcoholic, abusive husband who entertained at intervals the delusion that he was the second Christ, and whose “chief pleasure [was] to thwart and persecute his unhappy wife”. Taking up the pen at the age of forty-three under the compulsion of dire want, her literary income was deservedly higher than most of the other applicants, peaking at £320 in 1881, but it was unequal to the demands placed upon it’. In fact, Isabella only gave birth to eight children, only three of whom survived her. George died in 1881, and Isabella herself died in 1897. Ironically, it was Isabella’s devotion to her own very troubled man that inspired her prolific and extremely successful literary career.

Blog post by Patti Collins

4 Comments

Angela O'Gorman

Very interesting, thanks

P. B. Anderton (Mr)

I first read The Manchester Man when a pupil attending Manchester Central Grammar School. I have re-read it several times since. I recently bought a copy of Peterloo: The Story of the Manchester Massacre, which awaits my reading on a stack of my unread books. However, I doubt it will make the same impact on me that the Mrs Linnaeus Banks’ book made on me as a young teenager.

Elaine Godina

I read The Manchester Man 52 years ago when I first moved to Manchester. I also know of the Sun Inn group through its connection to Sam Bamford, and think about it most days when I walk that way from Victoria Station. I am often surprised by how few people seem to know about them.

Peter Taylor

Thank you for this fascinating and beautifully written blog post on Mrs Isabella Linnaeus Banks. I was especially interested in the references to John Bolton Rogerson, who is my great great grand uncle—his youngest sister was my great great grandmother. I’m currently researching his life and literary connections for personal interest, so I was delighted to see him mentioned as both a friend of Isabella Varley’s family and a founding member of the Sun Inn Group.

If possible, I’d be very grateful for any sources or further information regarding Rogerson’s friendship with the Varley family and his role in encouraging Isabella to join the Sun Inn Group. These details are of great interest to me as I try to piece together his literary and social networks.

Thanks again for the excellent work at Chetham’s Library, which I had the pleasure of visiting recently. Your dedication to preserving Manchester’s literary heritage is deeply appreciated.