- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

A Bluestocking Influencer – Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

A BLUESTOCKING INFLUENCER – LADY MARY WORTLEY MONTAGU

One of the most influential English women of the 18th century, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689-1762), lives on at Chetham’s library in the form of three collectors’ items: a volume of her early letters, a panegyric written by an admirer after her death, and a pamphlet touching on her turbulent relationship with the waspish poet Alexander Pope.

Born into an aristocratic family, classically educated through her own efforts and ambition in defiance of the times, she was betrothed at the advanced age of 23 by her father to an Irishman of suitable distinction (not least on account of his name – Sir Clotworthy Skeffington) whom she had never met. She described the wedding arrangements as ‘daily preparations for my journey to hell’ and eloped to marry her lover, Edward Wortley Montagu, just days before the ceremony. This spirited young woman continued to defy convention, becoming a prolific writer and a central figure both at court and in the literary and scientific circles of the Enlightenment.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, attributed to Jonathan Richardson 1667-1745 (Wikimedia Commons)

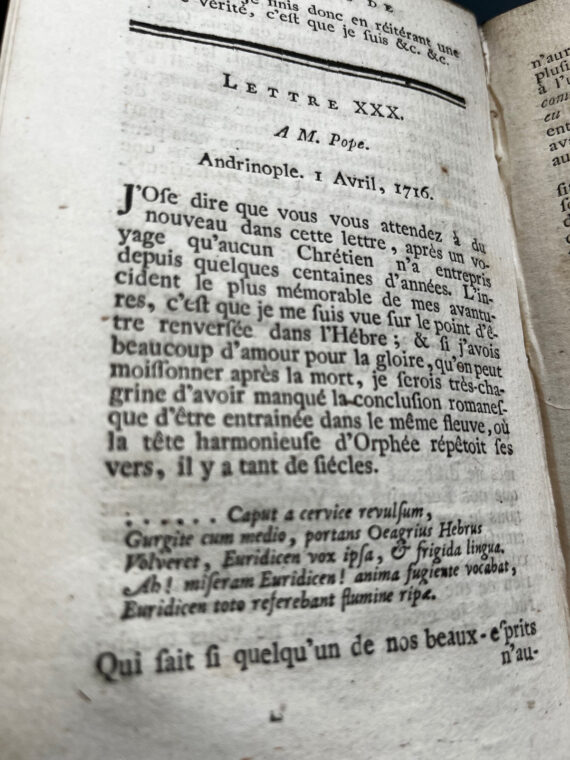

Travelling through Europe in 1716 and settling in Turkey, where her husband was English Ambassador at Constantinople, she recorded her experience in 58 letters in which she discusses, based on her acute observations, subjects ranging from the role of women, religion, oriental philosophy and politics to fashion, dancing girls, eunuchs, Turkish baths. These extraordinary pieces of extended writing were passed around certain circles during her lifetime but, in keeping with her wishes and the prevailing hostile climate for women who appeared in print, not published until after her death. They then appeared in 1763 as Letters of the Right Honourable Lady M–y W—y M—-e; written during her travels in Europe, Asia and Africa, to Persons of Distinction, Men of Letters etc in different Parts of Europe; Which contain, Among other curious Relations, Accounts of the Policy and Manners of the Turks. Additionally, she claimed that her letters were based on ‘Sources that have been Inaccessible to Other Travellers’, thus staking a claim to the authority of women’s writing.

Lady Montagu in Turkish Dress. Jean-Etienne Liotard c.1756 ( Wikimedia Commons)

The letters were a publishing sensation. A second edition was released the same year and even translated into French. Chetham’s copy is a first edition of that translation. One of the most interesting letters, written to Mrs S…C… in April 1717, describes an experience which would be life-changing for Montagu:

I am going to tell you a thing, that will make you wish yourself here. The small-pox, so fatal, and so general amongst us, is here entirely harmless. . . . There is a set of old women, who make it their business to perform the operation, every autumn, in the month of September, when the great heat is abated. People send to one another to know if any of their family has a mind to have the small-pox; they make parties for this purpose, and when they are met (commonly fifteen or sixteen together) the old woman comes with a nut-shell full of the matter of the best sort of small-pox, and asks what vein you please to have opened. She immediately rips open that you offer her, with a large needle (which gives you no more pain than a common scratch) and puts into the vein as much matter as can lie upon the head of her needle, and after that, binds up the little wound with a hollow bit of shell . . . .

Montagu had observed the practice of inoculation. Her brother had died of smallpox in 1713 and she herself was badly disfigured from having caught it in 1715. The following year (though it was not published until 1747)

in Town Eclogues:Saturday; The Small-Pox, she wrote of a victim of the disease:

wretched FLAVIA on her couch reclin’d,

Thus breath’d the anguish of a wounded mind ;

A glass revers’d in her right hand she bore,

For now she shun’d the face she sought before.

How am I chang’d ! alas ! how am I grown

A frightful spectre, to myself unknown !

Where’s my Complexion ? where the radiant Bloom,

That promis’d happiness for Years to come ?

The long poem goes on to satirise the patriarchy of physicians and the society in which women were made to feel that their beauty was the only way they could contribute. Horror of this dread and prevalent disease was widespread. After observing the Turkish custom Montagu swiftly arranged for her own 4 year-old son to be inoculated and, once back in London in 1721 at the height of a smallpox epidemic, she had the procedure repeated on her daughter, this time before an audience that included the King’s physician. What we would now call clinical trials followed (on prisoners and orphans) and eventually, two of the King’s granddaughters were inoculated and the practice spread. However, by the time Edward Jenner introduced the safer use of cowpox as a vaccine in 1796, Montagu’s efforts to eradicate smallpox had fallen into obscurity.

Medical advance and female fame have recently become a popular subject for study; scholarly debate continues on the extent to which Montagu influenced medical practice. It is certain that during her lifetime she was the object of both fulsome praise and vitriolic criticism. Her essay of 1722, ‘A Plain Account of the Inoculating of the Small Pox by a Turkey Merchant,’ and the conviction she showed by using her own children to make her case, caused shock waves. The chief objectors were the many members of the medical profession with a vested interest in traditional practices. Moreover, there was deep suspicion of what was seen as alarmingly oriental (classed with the ‘Heathen, Turk and Jew’) as well as what we might now call a gendered response; smallpox to men was a threat to life, while to women it was merely a threat to beauty.

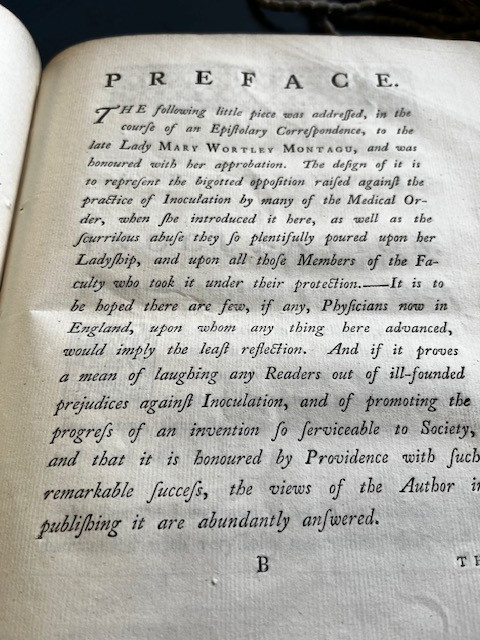

As well as her letters, Chetham’s Library holds a rare copy of a wonderfully overblown tribute to Montagu’s struggles.

The triumph of inoculation; :a dream (London : Payne, 1767).

“The Triumph of Inoculation; a Dream’ appears anonymously in a collection of pamphlets, but a note on the title page of the Bodleian copy names the author as Budworth Cruch, an apothecary. It tells the tale of a dreamer-narrator who finds himself in a hostile land, where ‘every object wore a melancholy aspect, and altogether formed a complete scene of disgust and horror.’ Ruler of this hell-hole, in a Gothic temple where human skulls ‘grinned horribly a ghastly smile’ was the evil goddess Variola (or,‘in the common style, The Small Pox’), supported by corrupt and mercenary doctors of the kind whose ‘scurrilous abuse’ was so ‘plentifully poured upon her ladyship.’ There suddenly appears, moving through the ‘sulphureous glare’ and ‘pestilential fumes’ and past scenes of inexpressible pain and grief, in a flash of lightning and clap of thunder, the glorious goddess, Health, who instantly transforms the gothic horrors into sweetness and light. This vision is led in by a female figure in English garb, whom the attendants address as ‘Inoculatia’. The piece concludes; ‘upon my asking (the name of) her benevolent conductress, I was waked, in a transport of joy, with the sound of ‘Montagu! Montagu!’’

The account of the dream was published in 1767, three years after Monatgu’s death. By this time her literary and intellectual reputation had been firmly established. Best known for her verse, written in the serious form of heroic couplets, she had early in life became friendly with the poet and satirist Alexander Pope and sent him witty letters from Turkey.

Letter to Pope in which Montagu humorously describes nearly falling in the River Hebre, then discusses legends, language, music and poetry

When Montagu returned to England the two poets collaborated comfortably at first, but Montagu found it necessary to guard her integrity as a woman poet; Pope later described her as calling out, when they were working together, ‘No Pope, no touching! For then whatever is good for anything will pass as yours, and the rest for mine.’ The gloves were off in their quarrel when, allegedly, Pope confessed his tender feelings for Montagu and she laughed in his face. More than a hundred years later this incident was dramatized in William Frith’s romantic painting of an operatic scene in which Montagu’s scars and Pope’s crooked back were airbrushed out.

Pope Makes Love To Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, 1852, by William Frith (1819 – 1909) (Wikimedia Commons)

Montagu went on to accuse Pope of stealing her verses; he retaliated in his long poem ‘The Dunciad’ implying that she was a prostitute and conflating smallpox with syphilis; she called him a toad-eater, mocked his obscure birth and hunchbacked body, and tried to erode his reputation as a clever satirist, writing: ‘Satire should, like, a polished razor keen,/ Wound with a Touch that’s scarcely felt or seen./Thine is an Oyster knife that hacks and hews;/The Rage, but not the Talent, to Abuse’. Pope upped his attacks on Montagu, ensuring that ever nastier, lewder verses of his were published anonymously.

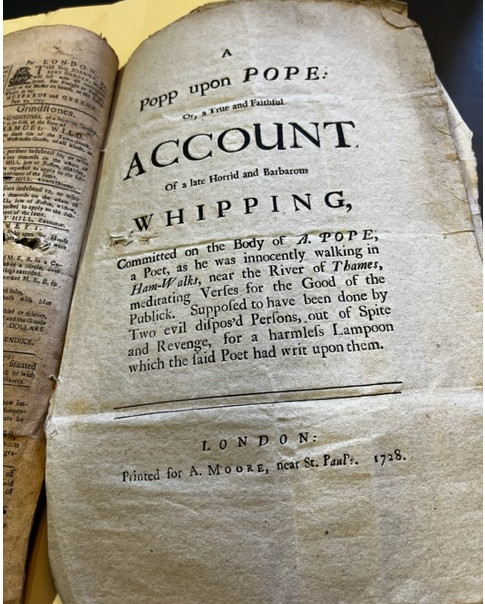

The third piece of Montagu memorabilia in our library touches on this stormy relationship between the two poets. Six years after their quarrel had begun, there appeared an anonymous pamphlet, ‘A Popp upon Pope: or a true and faithful account of a late horrid and barbarous whipping committed on the body of S-n-y Pope, a poet’ tells the sorry tale of how ‘Mr A Pope, a great Poet (as we are inform’d)’ was set upon by two Protestant thugs (Pope was a Catholic) who, after pretending to discuss The Dunciad with him, de-trousered him and struck so hard with a stable broom ‘upon his naked posteriors that he voided large quantities of Blood which being yellow’ was confirmed to have ‘a great Proportion of Gall mixed with it which occasioned the said colour.’ It now becomes clear that the whole piece is a clever satire which, while on the face of it commiserating with Pope and his suffering from the aftermath, then goes on to admire ‘the Wisdom of Providence, which brings this Man to the Lash, whose wanton wit has been the lashing of others’ and to hope that ‘when he returns to his senses, he will make better use of them and then may say…it’s good for me that I have been afflicted.” In other words, Pope got his just deserts.

‘A Popp upon Pope … Account of a late Horrid and Barbarous Whipping’ (London : Moore, 1728).

It is not surprising to find that this false account – even the bookseller’s name in the imprint is fictitious – was attributed to Lady Mary Montagu. In the 1730s she went to live abroad, well away from ‘the wicked wasp of Twickenham’ as she called him. She was mightily relieved when he died in 1744.

It would be unjust to define Montagu through this bitter dispute, even though it does tell us something about the ferocity with which unconventional women writers and thinkers were forced to defend their creativity and reputation. But for all the thousands of words from her poetic, if sometimes uncharitable, pen and despite the controversy about her contribution, she is still best remembered, as in her memorial below, as the person ‘who happily introduced from Turkey, into this Country, the Salutary Art of inoculating the Small Pox’ so that ‘by her example and advice we have softened the virulence and escaped the danger of this malignant disease.’

Memorial to the Rt. Hon. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu erected in Lichfield Cathedral. 1789

Kath Rigby

3 Comments

Andy Taylor

Fascinating, thank you. Just a small typo, she travelled to Turkey in 1716, not 1761.

ferguswilde

Thank, Andy, duly amended! Glad you found it interesting.

Keith Harris

A truly fascinating character who overcame the prejudices of the times. If only society in the 18th century was not so male dominated her influence would have been even greater. Many thanks for this interesting insight.