- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

A Tale of Manchester Life: The City’s Most Famous Literary Woman and Her First Novel

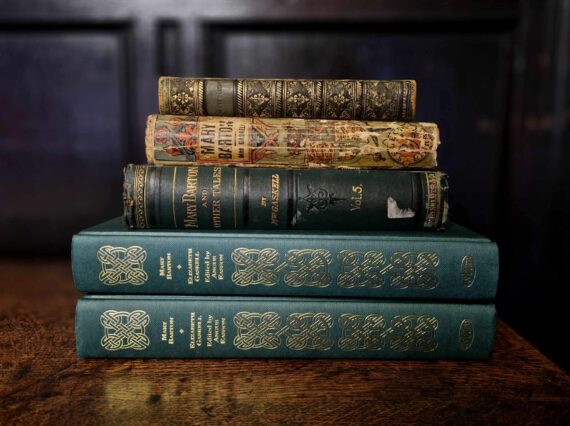

Recently, this blog has featured several posts about the literary women featured in Chetham’s Library’s current exhibition, A Woman’s Write. However, one figure not included in this exhibition is an individual who is arguably Manchester’s most famous literary woman: the author Elizabeth Gaskell. Gaskell lived in Manchester from 1832 to 1865, and her experiences of the city informed her depiction of working-class life in her novels. Today marks the 175th anniversary of the anonymous publication of her first novel, Mary Barton: A Tale of Manchester Life, and to celebrate the occasion, we’ve gone in search of the five copies of this work which can be found on our shelves. These range from a second edition printed in 1849 to a modern edition from 1993, and each of them has something to say about this work and its reception.

Fig 1: The five copies of Mary Barton held by the library.

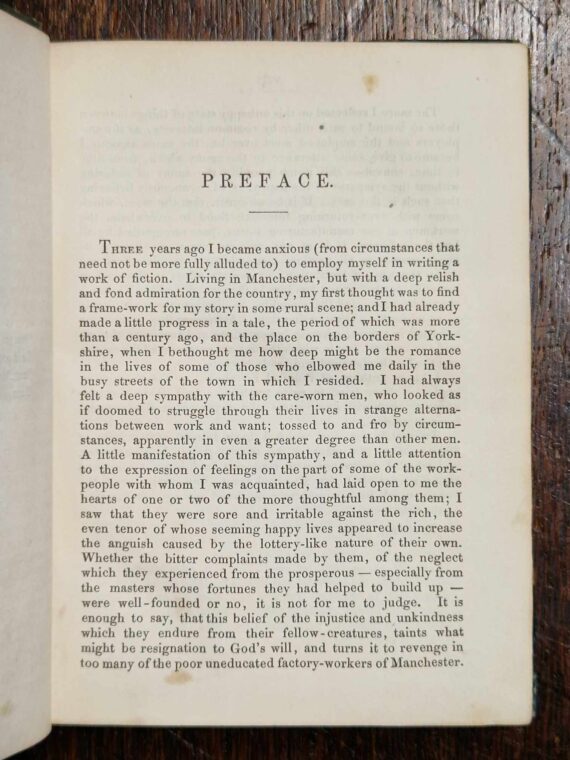

Our oldest copy of Mary Barton is a second edition printed in early 1849, only a few months after the novel’s initial publication and in response to its immediate success. This second edition corrected a number of typographical mistakes, particularly in instances of the Lancashire dialect Elizabeth Gaskell used to depict working-class life in Manchester. Gaskell herself played an active role in this process, sending several letters and a corrected first edition to her publisher, the London-based Chapman & Hall, in December 1848. One carry-over from the first edition was the novel’s anonymous publication, a tactic commonly (and often necessarily) employed by female authors, including several featured in A Woman’s Write. As a result, Elizabeth Gaskell’s name appears nowhere in our earliest copy of Mary Barton, and this anonymity actually aided the novel’s initial success; speculation abounded as to the author’s identity, which Gaskell herself even engaged in! Another noticeable carry-over from the first edition was the inclusion of a preface to the novel written by the author, which would disappear from later editions.

Fig 2: The preface of the second edition (1849) of Mary Barton.

Elizabeth Gaskell’s first novel was influenced by the hardship experienced by both herself and Manchester’s working class. In the novel’s preface, she noted that she ‘became anxious (from circumstances that need not be more fully alluded to) to employ myself in writing a work of fiction’; it is now known that the circumstance she was referring to was the death of her infant son, William, in 1845. Her husband, the Unitarian minister William Gaskell, suggested that she take up writing to ‘soothe her sorrow’, and Elizabeth Gaskell wrote to her friend Mrs Greg in 1849, telling her that she ‘took refuge in the invention to exclude the memory of painful scenes which would force themselves upon my remembrance’. At the same time, the preface makes it plain that the plight of the working class also moved her; while she had initially begun writing a historical work set on the rural borders of Yorkshire, she began to wonder whether there might be a deeper romance in the lives of those who she saw while out and about in Manchester: ‘care-worn men, who looked as if doomed to struggle through their lives in strange alternations between work and want; tossed to and fro by circumstances’.

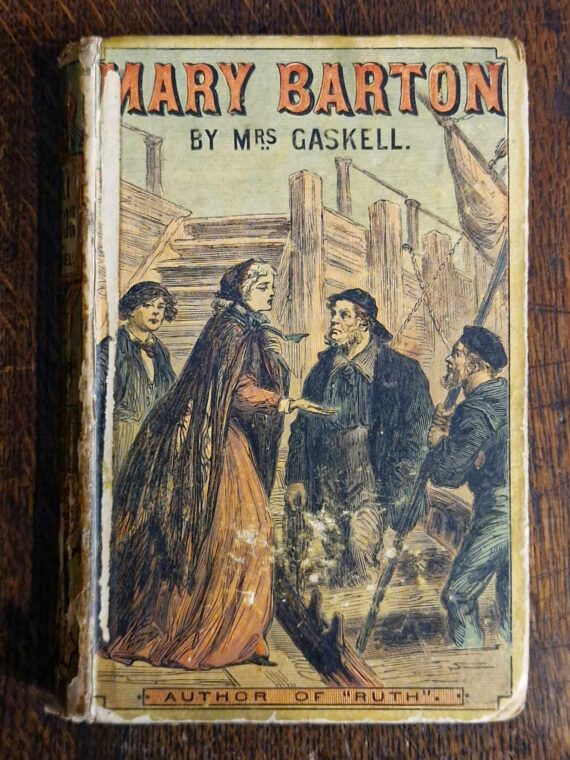

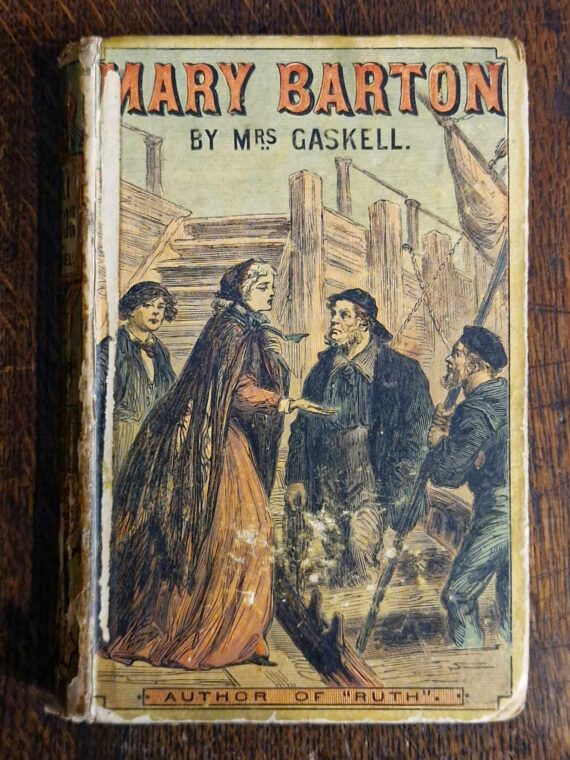

Fig 3: The cover of the tenth edition (1867) of Mary Barton.

Mary Barton was reprinted several times in quick succession, and by 1850 the novel was already on its fifth edition. By this point, Elizabeth Gaskell was less involved in the publication process, having learnt of the fourth edition only after seeing it advertised! Our next oldest copy of Mary Barton is a tenth edition, issued in 1867 by Chapman & Hall as part of the Select Library of Fiction. This series aimed at offering ‘the best, cheapest and most popular novels’ by the best authors at two shillings apiece, a price reflected on the spine of this book. Inside its front and back covers, double-page spreads list other works available in the series, ‘sold by all booksellers, & at railway stations’. The covers themselves are much more visually appealing than before, with illustrations of the novel’s events intended to entice potential buyers. Two further changes from earlier editions are also evident: for the first time on our shelves, Elizabeth Gaskell was prominently named as the author on both the cover and title page, while at the same time, the preface was no longer printed alongside the novel.

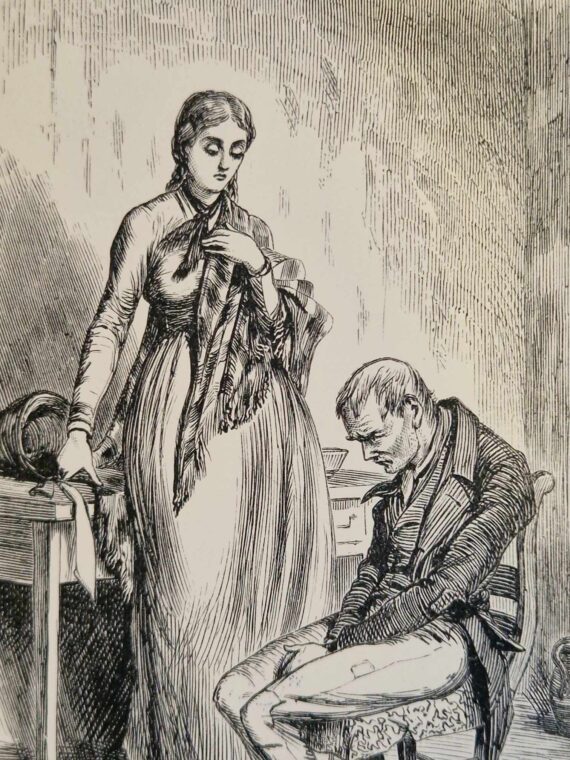

Fig 4: An illustration of Mary and her father, from the 1881 edition of Mary Barton.

Our most recent historical copy of Mary Barton was published in 1881, by Smith Elder & Co., as Mary Barton and Other Tales: the fifth in a seven-volume series of Elizabeth Gaskell’s works. In this edition, the preface was once again omitted, but for the first time the chapters received titles: the first chapter, previously known by its number, was now named ‘A Mysterious Disappearance’. Although the cover of this edition is unillustrated, the text contains four printed plates, the first of which depicts a tender moment between Mary Barton and her father from near the end of the novel. The other illustrations accompany five shorter works by the author, which were included alongside the main novel.

The last two copies of Mary Barton on our shelves are identical, modern critical editions of the novel published in 1993. In them, the novel is prefaced by an introduction, a pair of short notes which provide biographical information about Elizabeth Gaskell’s life and the development of the work, and suggestions for further reading, while it is followed by almost thirty pages of explanatory notes. For the first time since our second edition, Elizabeth Gaskell’s own preface has also been printed at the beginning of the novel. The copies of Mary Barton on our shelves therefore represent the novel’s journey from contemporary fiction to a literary classic, worthy of study. Despite its success soon after publication, Mary Barton is today overshadowed by Elizabeth Gaskell’s most famous novels, Cranford and North and South. Gaskell’s first novel is no less deserving of attention, though, for what it tells us about working-class life and a remarkable literary woman.

By Emma Nelson.

7 Comments

Victoria Owens

What a wonderful article. So intriguing about ‘Mary Barton’s’ early publication history. I have a copy of the Smith Elder edition which I bought in the mid-1970s from a 2nd hand bookshop in Bucks for 75p. I’m not sure what that says about economics of the antiquarian booktrade of the time, but I remember cycling home very pleased with my purchase. I must have been about fifteen or sixteen years old. Almost fifty years later, notwithstanding the Penguin Classics edition which I bought as a student for Lit Crit purposes, recollection of my delight at finding the old copy remains keen as ever.

ferguswilde

Thanks, Victoria! Delighted to hear you enjoyed the blog. A copy that’s been with you for life is certainly a thing to hold on to for good!

Sue Richardson

Really interesting write-up and a good indication of how the world of publishing has changed! Thanks!

ferguswilde

Thanks, Sue, that’s a nice compliment coming from a pubisher!

Elaine Godina

Enjoyed this. “Mary Barton” is featured in the current exhibition at Elizabeth Gaskell’s House, along with her other Manchester novels. Visit the Gaskell website for further information.

Elaine Godina

See the current exhibition at Elizabeth Gaskell’s House, 84 Plymouth Grove, to learn more about Mary Barton’s Manchester.

ferguswilde

Thanks Elaine! We certainly recommend Gaskell’s House to all readers, do go along to see the exhibition.