- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Apples and ale with Christmas tale will make a household merry

The current season of Christmas songs and carols carries on a centuries old tradition.

The first Christmas celebrations may have drawn upon pagan customs, but our earliest reference to Christmas by that name is attested in 1038 as Cristesmæsse. As Dr Tim Flight tells us in his reading of Bede, the dating of Christmas at 25 December owes much to this pagan past, and to Pope Gregory the Great’s injunctions to his missionaries to re-use pagan dates and places.

Carols themselves started as a dance, and only slowly have the accompanying songs become the main event and eclipsed the movement of the dance. In the medieval period Christmas hymns were part of the office of prayer, and limited in their performance and perhaps mainly in their audience to clergy with at least some Latinity. The English language provided songs and rounds all could sing, though, and there are many survivals of such songs from the fourteenth and fifteent centuries, such as this one from c. 1410:

“I saw a sweet, a seemly sight,

A blissful burd, a blossom bright,

That mourning made and mirth among:

A maiden mother meek and mild

In cradle keep a knave child,

That softly slept; she sat and sung,

Lullay, lulla balow,

My bairn, sleep softly now.”

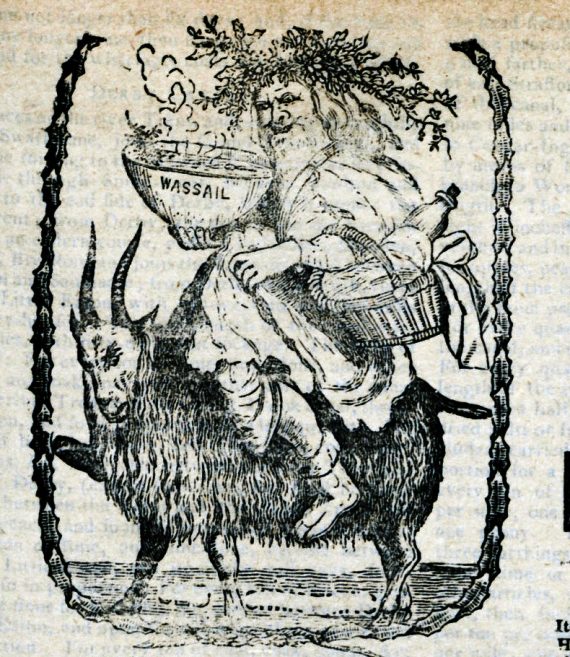

Many other carols, as befits their popular origins, were festive in a quite non-religious sense, and the authorities across Europe made efforts from time to time to clean up or suppress bawdy and boozy singing.

The toughest ‘zero-merriness-tolerance’ approach to the whole feast came when Oliver Cromwell and the puritans banned them altogether between 1647 and 1660.

Cromwell – the grinch that stole Christmas

They reappeared in public after the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660.

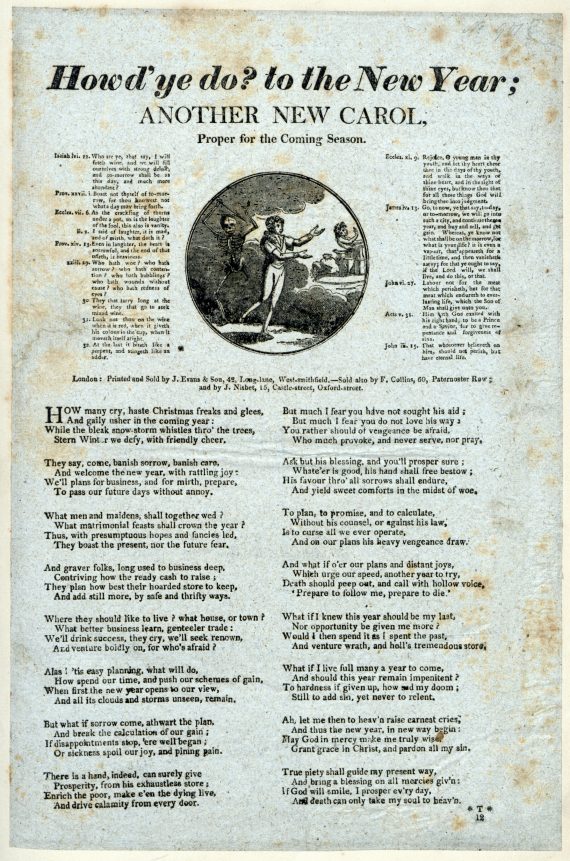

Here at Chetham’s we’ve been digitising our Halliwell-Phillipps collection of broadsides and ballads, and quite a few post-Restoration numbers have found their way into the collection and our project – please enjoy them and have a Merry Christmas or the feast you prefer with some of these Cliff Richard beaters:

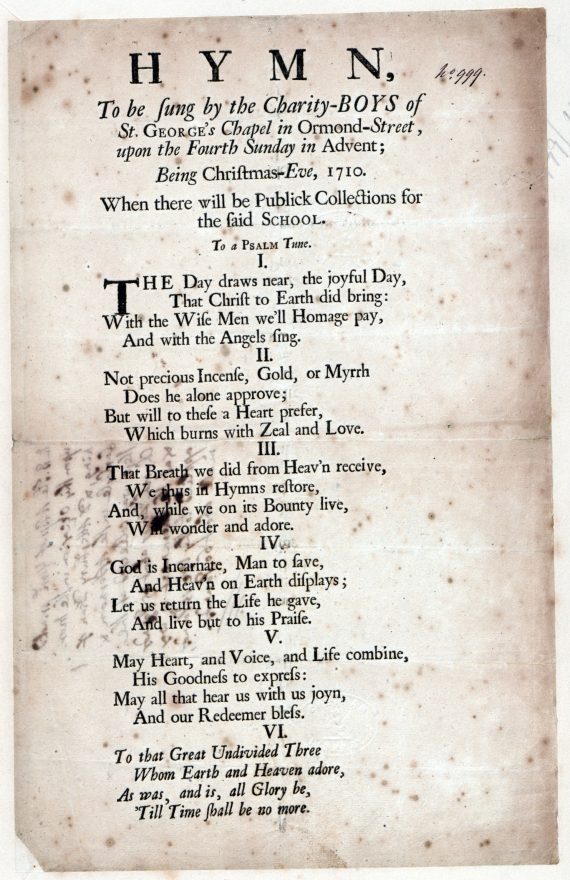

Hymn, to be sung by the charity-boys of St. George’s Chapel in Ormond-Street, upon the fourth Sunday in Advent; being Christmas-Eve, 1710.

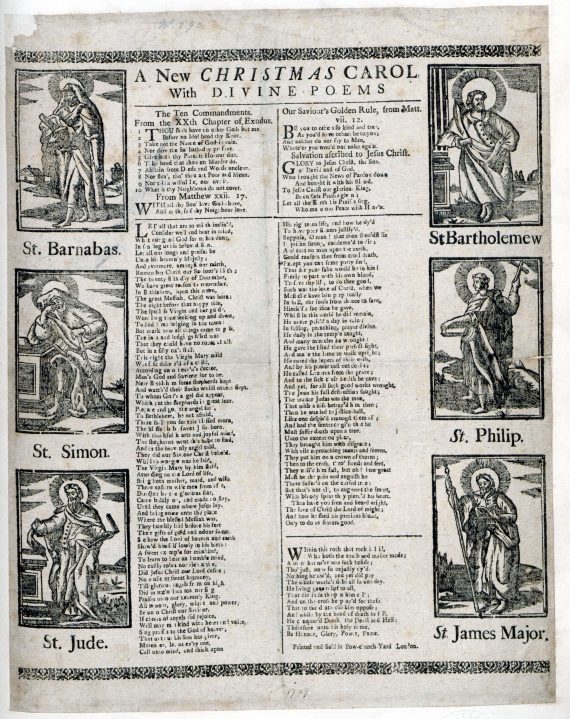

New carols were printed on broadsheets and sold on the streets. These single sided song sheets, which were often decorated with woodcut illustrations of saints or religious scenes, were frequently printed on poor quality paper, often with uneven inking, as they were cheap and perhaps often considered throw away items. Some did survive however, and the library is fortunate to have examples of 18th and early 19th century carols in the Halliwell–Phillipps collection. This collection, which was presented to the Library in 1852 by the Shakespearean scholar James Orchard Halliwell Phillipps, contains 3,100 items of printed ephemera. The thirty one bound volumes include a wide range of material from royal proclamations to broadsides, ballads, poems, sheet music, trade cards, bill headings and advertisements items from the end of the seventeenth and early eighteenth century. This fascinating collection has recently been digitised and can be viewed on-line.

A New Christmas Carol with Divine poems was produced around 1750. It is illustrated with woodcuts and a horizontal ornamental border across the top and bottom.

Carols gradually became respectable during the 18th century although they were still rarely sung in churches. Their popularity rocketed in the nineteenth century as the Victorians developed the Christmas traditions we know today: a family celebration, a holiday from work, presents, decorated trees, crackers and Christmas cards. William Sandys and Davis Gilbert published a book of carols which also helped to popularise them.

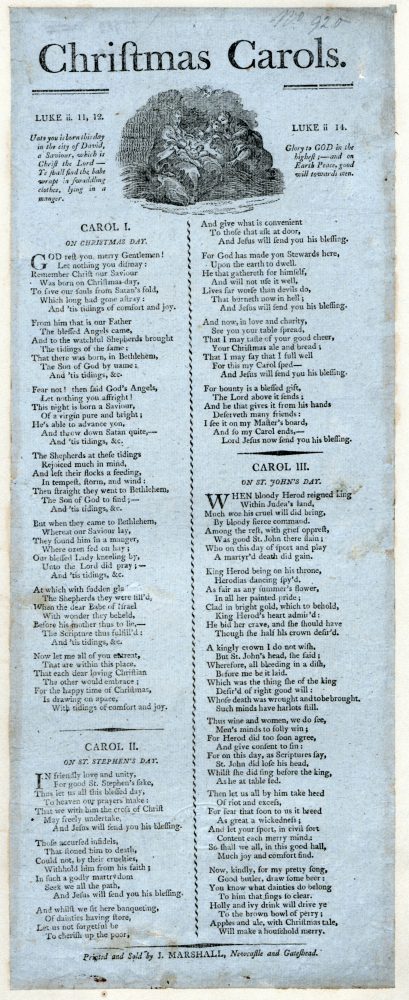

Christmas Carols was printed between 1801 and 31 and is illustrated with a nativity scene. The first carol is God Rest You Merry Gentlemen, a traditional 15th century Christmas carol which we still sing today. Charles Dickens’ used it in A Christmas Carol: ‘… at the first sound of “God bless you, merry gentlemen! May nothing you dismay!” Scrooge seized the ruler with such energy of action that the singer fled in terror, leaving the keyhole to the fog and even more congenial frost.’

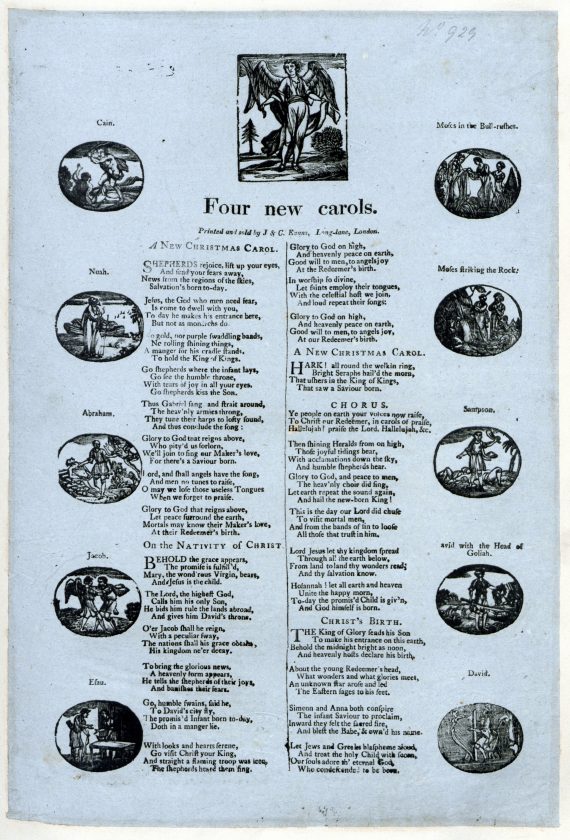

Four new Carols, printed around 1820 with captioned woodcut illustrations

Carols became established in church services during the nineteenth century, and in the 1870s the Truro Cathedral choir sang carols inside the cathedral rather than in the streets. The Bishop of Truro created the Nine Lessons and Carols service which has been in use ever since and many readers might listen to a contemporary version broadcast from King’s College Cambridge on Christmas Eve.