- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Chetham’s Library, Book Historians and Book Lovers

We were very pleased to receive this blog post from last year’s researcher-in-residence, Verônica Calsoni Lima. Verônica was with us for some extended research into censorship in England in the Restoration era, and gave a public lecture on the subject in our Baronial Hall. Here she reflects on some aspects of working on our collections and exemplifies some of what can be learned from particular copies of early printed books. Verônica writes :

I would venture to say that everyone interested in visiting Chetham’s Library is a book lover. I also think that everyone who has had the privilege of walking around its stone walls and wooden shelves, has marvelled at the library’s beauties. The building itself, a 15th century construction, astonishes, and the treasures kept inside, which are from a variety of places and periods, are even more breath-taking.

As a book historian, Chetham’s Library was a must-see for me. As the oldest public library in Britain, it has an amazing collection of manuscripts and printed texts which can supply sources for all sorts of research projects. I had the great opportunity to visit the library and consult its books, pamphlets and documents regularly as a research fellow between 2018 and 2019. The time I spent there was extremely important for my current research on 17th century seditious and clandestine ephemera in England. Besides being able to locate texts related to my subject, Chetham’s collection provided me with many unexpected materials which expanded my knowledge and challenged me with surprising pieces.

Chetham’s texts have a long history not only because of their issuing date, but also due to their provenance and permanence in the collection. As polysemic and meaningful objects, books carry several marks of their existence and use. They might have been read many times by different people who left notes; they might have been kept together with other texts suggesting a reader’s agenda; they might be bound or not, torn apart or in perfect shape. Every detail helps book historians to understand a little more about them. In this post, I want to introduce a snippet of what can be found when consulting Chetham’s items.

Most libraries have rebound their books for conservational and organizational purposes. Sometimes covers have been so destroyed by insects, fungus and chemical reactions that they could compromise the integrity of the entire volume, hence requiring a replacement. Other times rebinding aimed to better accommodate the items on the bookshelves. Although libraries have discarded many covers, nowadays they take extra effort to preserve original bindings since they provide amazing sources of information about books’ provenance. This happened at Chetham’s; however, a great number of items remain still untouched.

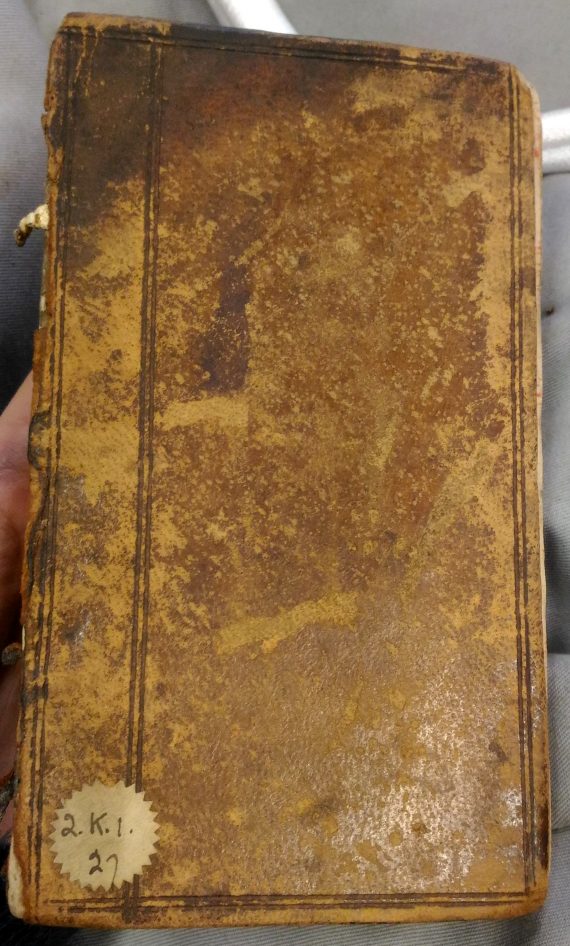

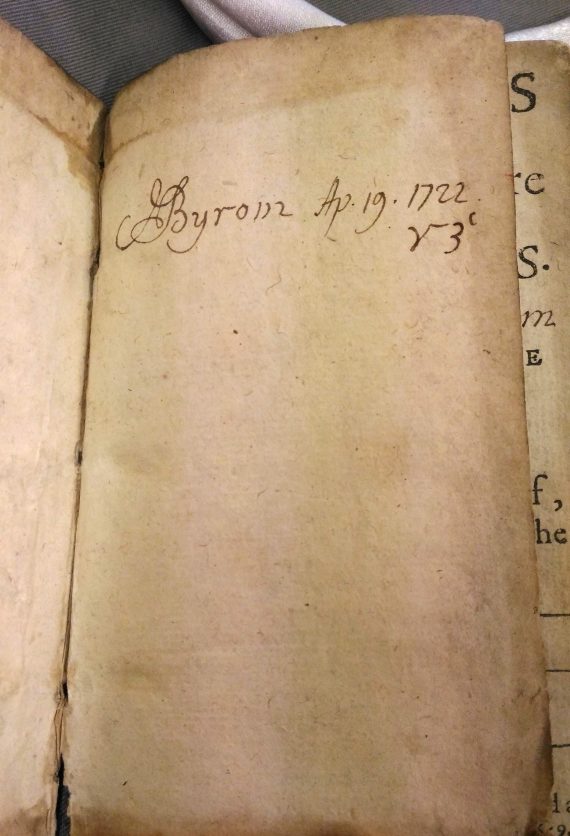

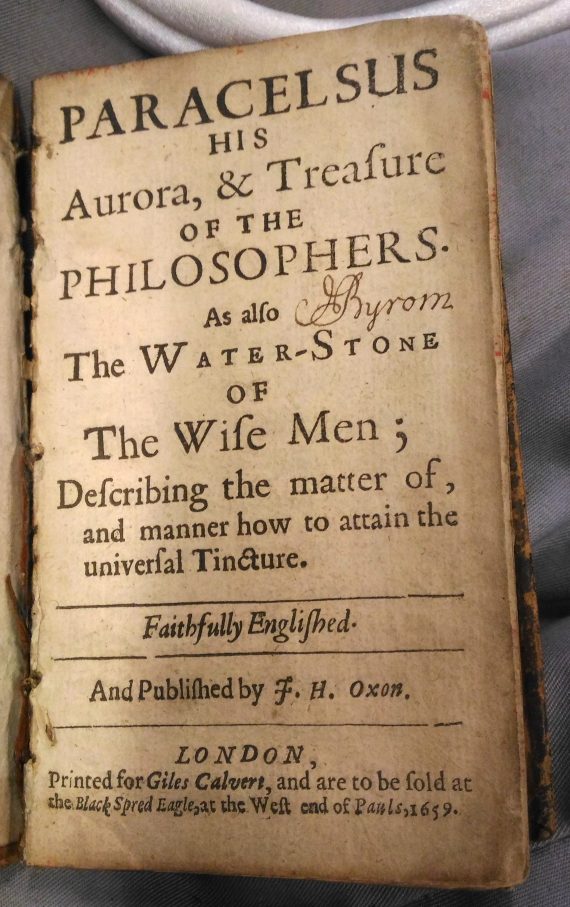

In John Byrom’s collection kept at Chetham’s Library, for example, we may find 18th century bindings, as in his copy of Paracelsus’s Aurora of the Philosophers (1659). As it is a 17th century edition of the book, this may not be its first cover, but this is the cover which shielded the book while it was in Byrom’s private library. In fact, books were usually sold unbound and were kept like that unless the owner was wealthy enough to take his/her items to a bookbinder. For specialists on bindings, this specimen provides useful information about the books’ circulation (was it bound in England or elsewhere?) and provenance (who owned it?), the techniques used in the manufacturing (what is the material of the cover? How was the spine constructed?), and when it was acquired (are there dates or other details which indicate a period?).

Figure 1: BYROM 2.K.1.27

Figure 1: BYROM 2.K.1.27

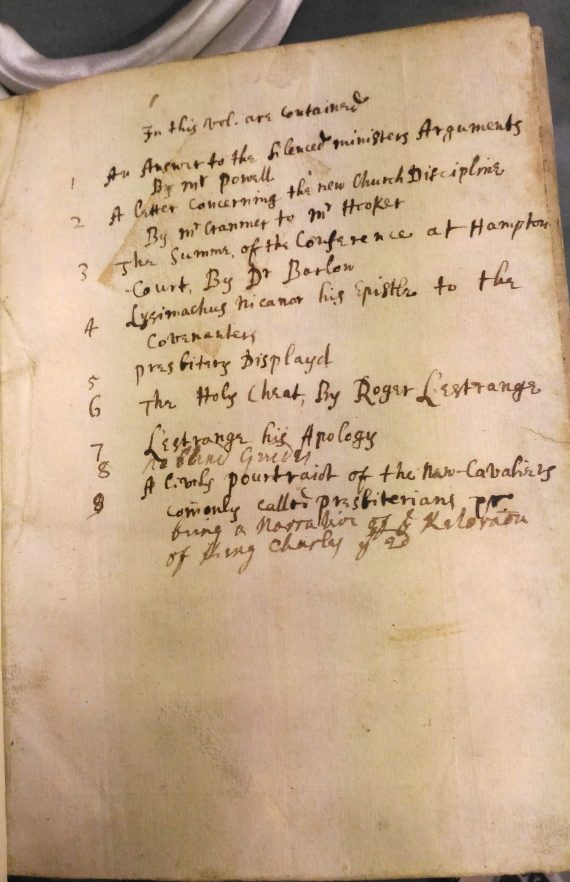

Both in old and modern bindings, Chetham’s has many Sammelbändes. According to Jeffrey Todd Knight, Sammelbändes are book compilations bound together by an owner interested in interacting with his/her texts. Sammelbändes usually reflect readers’ interests and perspectives, suggesting interpretations and appropriations of the writings they owned. This Renaissance practice of binding different texts together is responsible for allowing many ephemera to survive. Owners would not spend money purchasing a cover for a small pamphlet, ballad or news sheet, but would see no problem in attaching it to more valuable items. Volumes organised by previous owners did not always remain unchanged. Later owners or libraries might have altered them. As Sammelbändes are complete miscellanies, they did not necessarily have homogenous features (such as genres, sizes, formats, etc), therefore, modern libraries tended to unbind some volumes and restructure them according to subjects, textual genres or sizes (in order to fit bookshelves). The volumes collected by Anthony Wood in Oxford, for instance, have been modified multiple times since they arrived at the Bodleian. Librarians, archivists and historians are sometimes able to reassemble the original organisation thought by early readers, but lots of information are lost in the process.

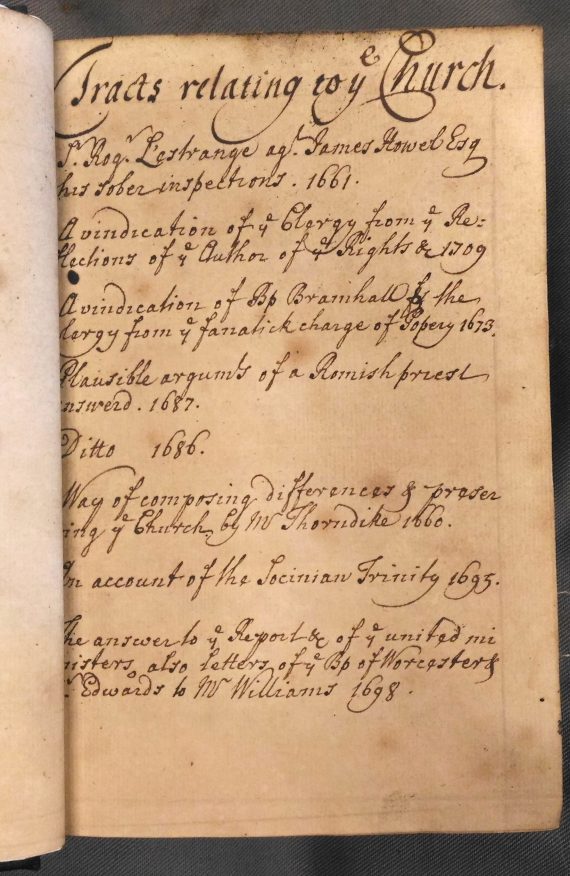

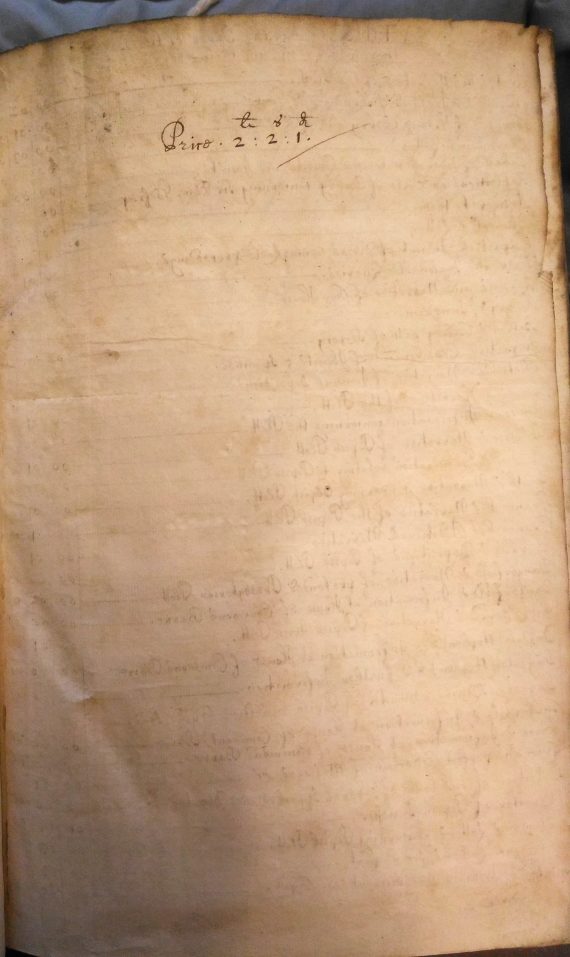

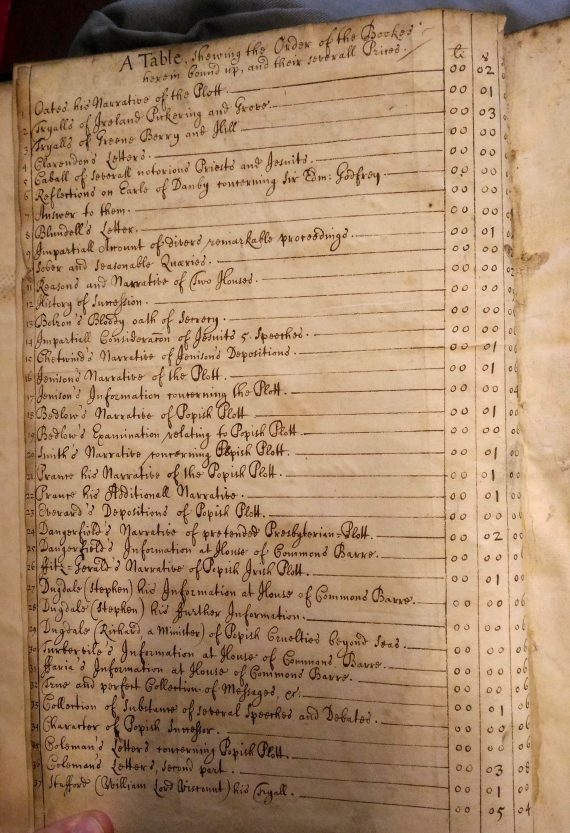

Although many volumes have been rearranged in Chetham’s Library throughout its history, we still find many types of Sammelbändes. Some specimens even carry indexes, such as the examples below. These tems may tell us many details about early owners or even the library’s former cataloguing practices.

Figure 2: MAIN H.3.77 and MAIN 4.C.2.35.

Occasionally collectors were kind enough to provide us the prices of individual items and/or the entire volume, allowing us to consider the economic history of the book in Early Modern England.

Figure 3: W4.47.13337.

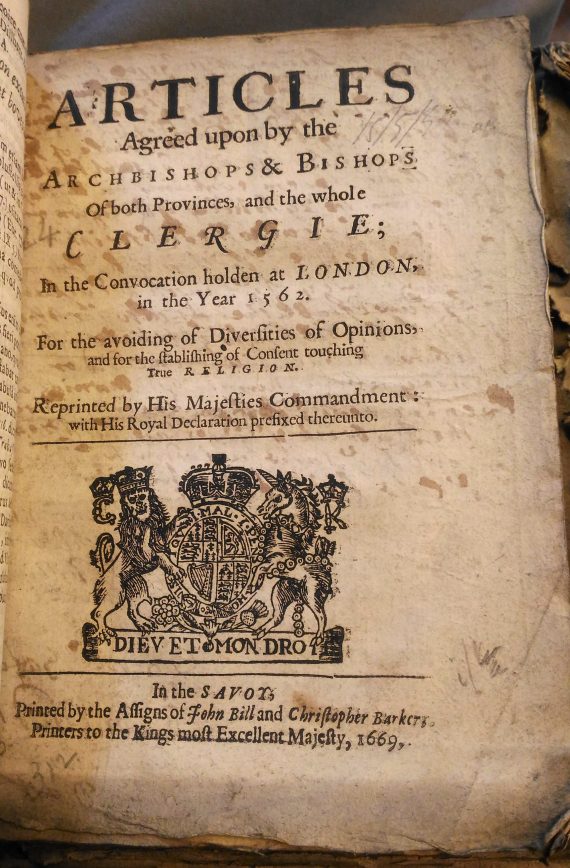

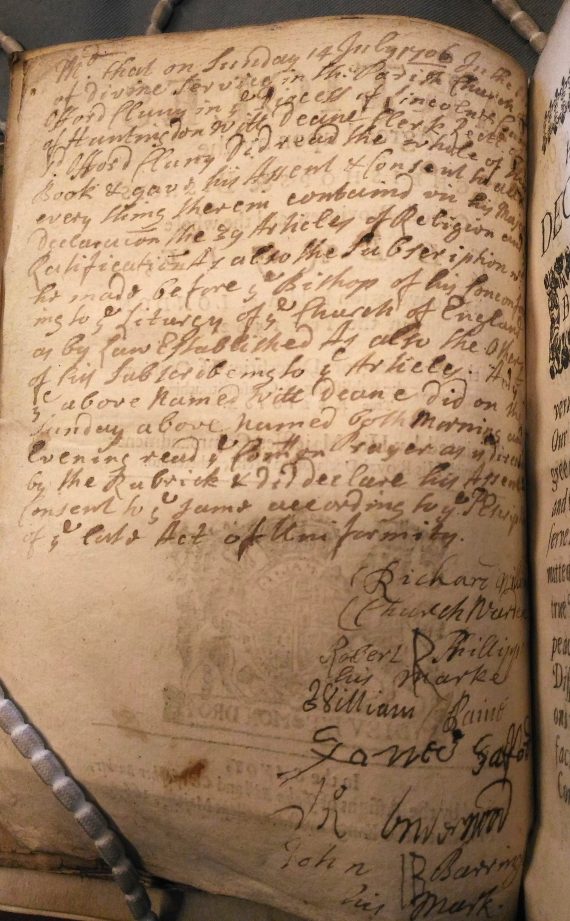

Readers’ and owners’ notes are always extremely helpful to researchers, since they provide us glimpses into how texts could have been interpreted and understood in the past; or even how paper was reused in the past (as paper was very expensive, it is not unusual to find notes unrelated to the topics of the book, such as diary entries, lettering studies, lists, etc). On the verse of this text title-page, for example, there is an annotation dated from 14th July 1706 mentioning a discussion on the subjects of the Articles Agreed upon by the Archbishops & Bishops (1669) between Church ministers.

Figure 4: WATT 11.C.2.20(6).

Chetham’s collection is a perfect example of how libraries and archives are evolving institutions. As researchers with short deadlines and multiple tasks to carry on, we are used to simply requesting and studying a specific item, without paying attention to the text’s surroundings. Nevertheless, the fascinating books available at Chetham’s Library compel us to explore further details, leaf through small or large volumes alike, and understand the broader context of written materials. Books at Chetham’s (if I may borrow John Milton’s words) are not dead things, they can still surprise us more and more. I invite curious readers, book lovers and book historians to spend some time there reading and discovering more about the past.

1 Comment

Geraldine Beare

Ah – the wonder of books and libraries. As a long-time member of The London Library, serendipity – and the joys of stumbling unexpectedly on items unknown!