- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Flights of Fancy

One of the most notable features of the Reading Room at Chetham’s Library is a stunning carved and painted tympanum above the fireplace featuring heraldry and emblems relating to Humphey Chetham, the founder of the Library and School. The craftsman has included images of two symbolic birds: a cockerel to suggest vigilance and hard work and a pelican feeding her young with her own blood, a traditional symbol of Christ’s sacrifice.

Reading room

From the earliest times humans have seen birds both as a source of food (the farming of poultry and the use of hawks for hunting developed long before written records began) but also as mysterious creatures with supernatural connections to all things celestial. At the Library we currently have on display a small selection of the library’s books about birds dating from the seventeenth to the twentieth century.

The earliest books about birds were based largely on superstition, folklore and writings by previous authors. Aristotle, the Greek philosopher and scientist, was an inspiration to early naturalists but his mistaken belief that swallows hibernate in mud over the winter continued for centuries. The story of the pelican feeding her chicks with her own blood was also accepted as scientific fact for several hundred years.

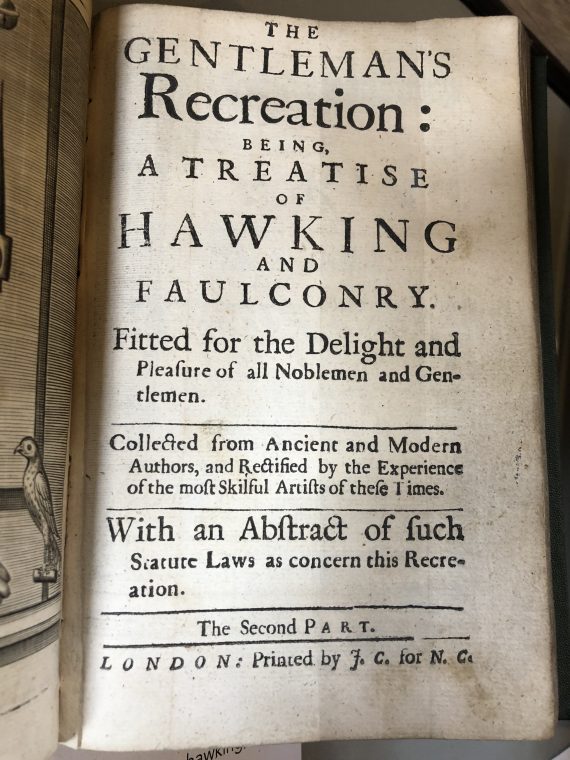

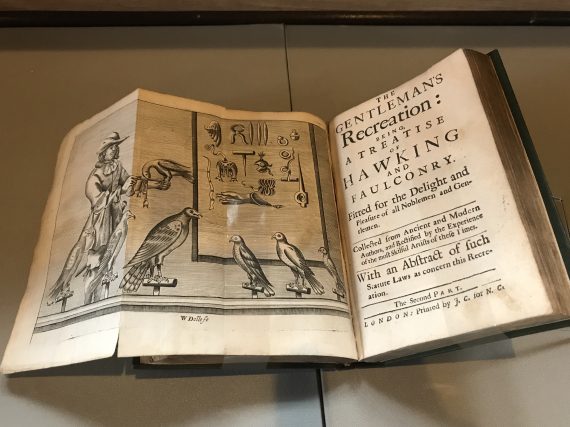

In contrast to these ‘flights of fancy’, the British Library owns a surprising number of medieval manuscripts which were written as very practical manuals on hunting and hawking. We have included an early printed example from our own collection, by Nicholas Cox, published in 1677:

The gentleman’s recreation: in four parts, viz. hunting, hawking, fowling, fishing. Wherein these generous exercises are largely treated of, and the terms of art for hunting and hawking more amply enlarged than heretofore.

Gentleman’s Recreation

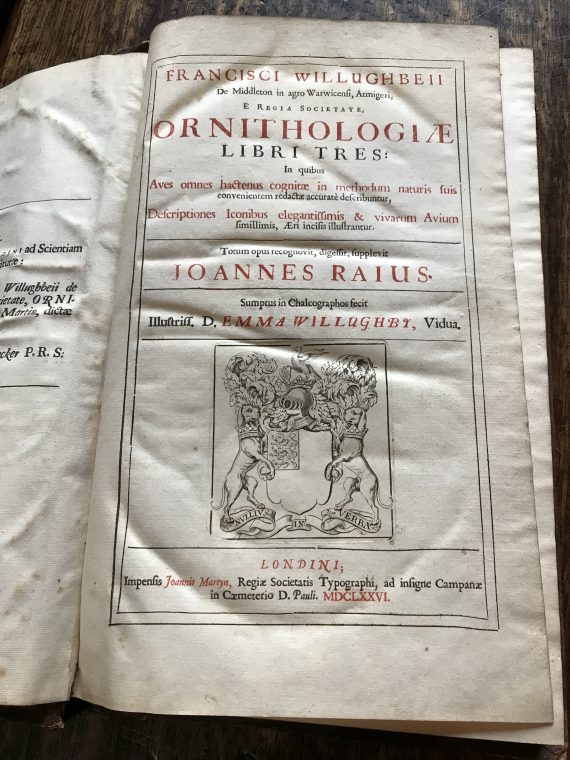

The work which many scientists believe changed everything, the first truly scientific study of birds, was published (in Latin) in 1676:

Willughby’s Ornithology (1676)

Willughby was an exceptionally clever and very wealthy young man who was fascinated by natural history. John Ray (the son of a blacksmith) was his Cambridge tutor, friend and colleague. The pair travelled within Britain and abroad in the 1660s and the classification system which they developed still forms the basis of current systems. Firstly they divided birds into land or water birds. Then land birds were divided into those with crooked beaks and claws and those with straight beaks. Water birds were basically either ‘waders’ or ‘swimmers’.

Sadly, Willughby died at the age of 36 years so Ornithologia was edited by Ray and published posthumously in London in 1676. (An English edition, Ornithology, followed in 1678 and Chetham’s has a copy of this also.)

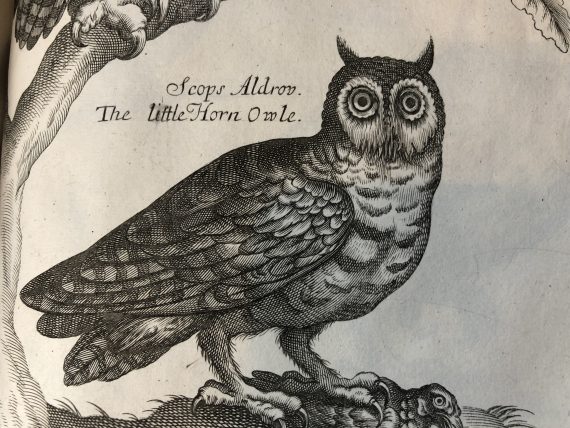

Interestingly, Willughby’s wife Emma paid for the 80 metal-engraved plates that completed the work, and this is acknowledged on the title page. The 77 illustrations came from various sources, some were copies made from the collection of pictures and specimens owned by Willughby, while others were commissioned by Ray.

Willughby’s Ornithology

From this time the scientific description and classification of different species became increasingly important, as overseas voyages and expeditions discovered many new and exotic birds and brought home specimens.

Illustrations were recognised as being essential in books about birds but the quality varied greatly. Those drawn from specimens (dead or alive) tended to be more accurate than those taken from sketches made in the field.

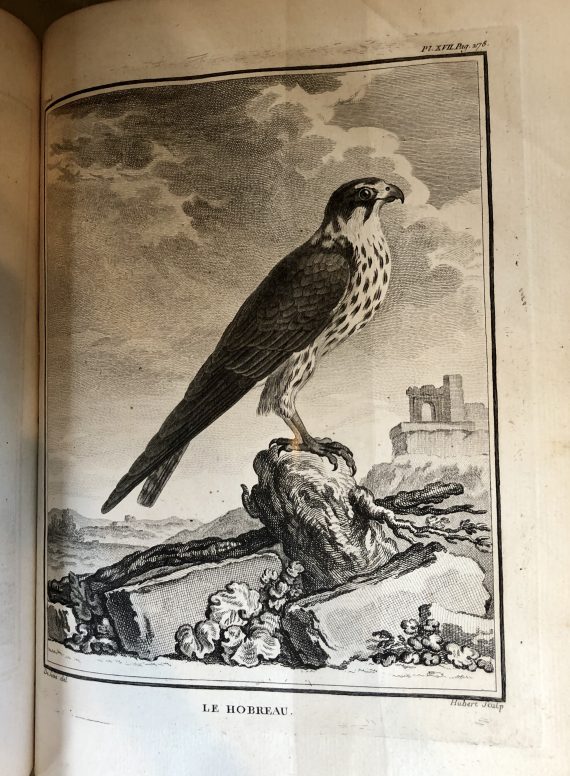

Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière (1749-1804)

The elegant image of a Hobby posed against classical ruins is from one of the nine volumes on birds which were part of Buffon’s Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière published in Paris between 1749-1804. The Histoire was an ambitious project to produce an account of the whole of nature in 50 volumes by Georges Louis Leclerc, later Count de Buffon, who became keeper of the Jardin du Roi (Royal Botanical Garden) in Paris at the age of 32.

The Histoire was designed as much as a coffee table book as a scientific work and it was a great success. Wealthy homes in both England and France purchased copies, and the first edition was sold out within six weeks. However, Buffon was much criticised by scientists for his unscientific approach, by theologians for expressing views which challenged the biblical account of creation and even by writers and academics for his flowery, over-elaborate writing style.

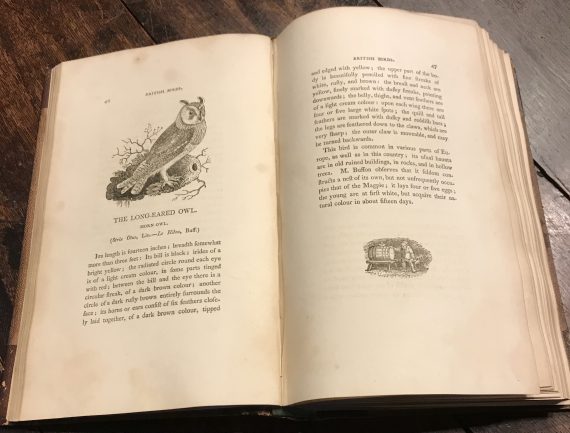

A completely different work of ornithology, published at the same time as Buffon, was The History of British Birds (1797-1804) by Thomas Bewick, the 18th-century wood engraver famed for his finely-detailed, imaginative illustrations. Bewick’s revolutionary technique and artistic skill are said to have revived the medium of wood-engraving. The History of British Birds examines each major British bird species, with detailed written observations and precise engravings. But the book also contains unusual ‘tail-pieces’, small images often no bigger than a coin that fill the available space at the end of a chapter. These images depict a wide range of subjects, from innocent scenes of rural life to bizarre and disturbing fantasies featuring drunks, fools and devils.

History of British Birds

Both ornithologists and the general public were delighted and beguiled by Bewick’s work. His famous contemporary John James Audubon, the American ornithologist, naturalist, and painter, praised it, enthusing about the little tail pieces, and in Charlotte Bronte’s novel, Jane Eyre declares that ‘with Bewick on my knee, I was then happy…’

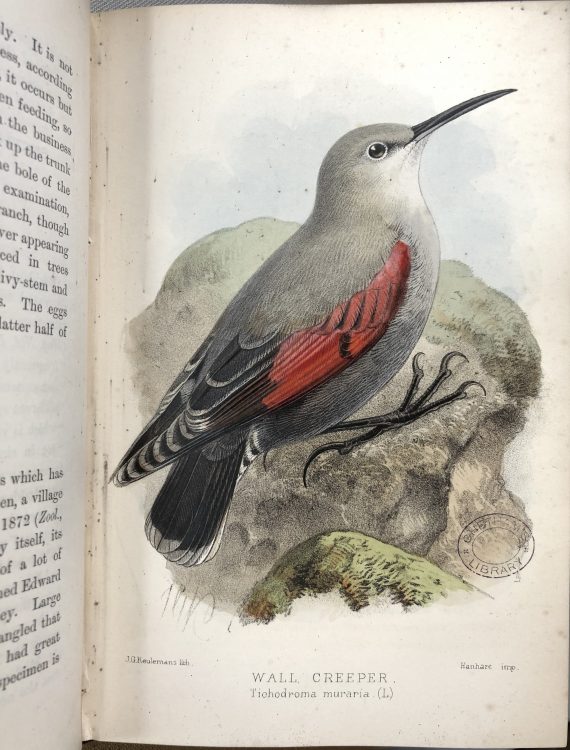

Another northern bird enthusiast was Frederick Shaw Mitchell, author of The Birds of Lancashire, published in 1885. His family owned the Primrose Paper Mill near Clitheroe where Fred was a manager, but in 1880 they were taken to court for allegedly polluting the river Ribble and were found guilty. It was a financial disaster from which they didn’t recover, and in 1891 Fred and his wife Lizzie emigrated to Canada and became ‘homesteaders’, settling in a log cabin and bringing up their family there, never to return to Lancashire.

Wall Creeper

Ironically, Fred had written about the impact of industry on birds in the book:

‘The way in which birds are driven away by the extension of buildings, and by the conversion of a rural into an urban locality may well be instanced by the case of Peel Park, Salford … Mr John Plant has kindly permitted me to use his notes, which have been carefully kept since 1850 and show…’ [A table is inserted here showing a decline from 71 species observed in 1850-60 to a mere 5 species in 1882]. He goes on to discuss the impact of destruction of natural food, loss of protective foliage etc and of the ‘vitiated atmosphere’.

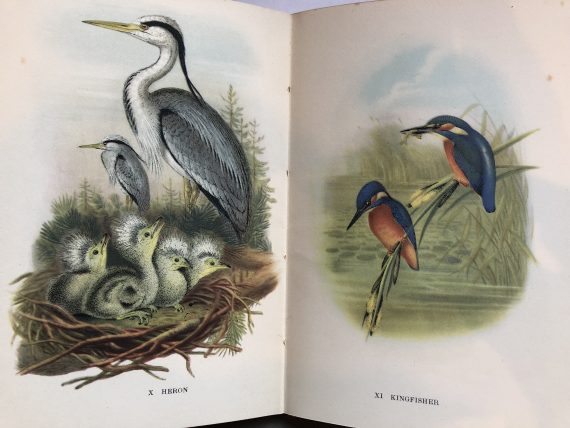

Our final two selections are from the famous twentieth-century series of King Penguins. This series covered a variety of topics and ran to 76 volumes with the final book published in 1959. The covers were original commissions but the illustrations in the earlier books were often reproductions of the work of well known artists. We have a copy of the very first book in the series British birds on lake, river and stream, written by Phyllis Barclay Smith and published in 1939, just a few weeks after war broke out. The book used images taken from John Gould’s celebrated work Birds of Great Britain first published between 1863-73 and often described as the most sumptuous and costly of British bird books.

Colour plates by John Gould for British birds on lake, river and steam (Penguin, 1939)

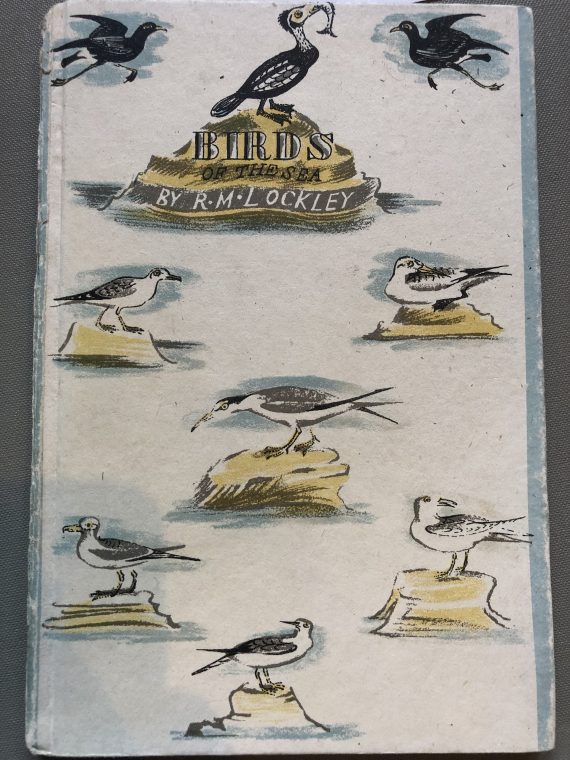

Our other King Penguin is Birds of the Sea published in 1945, which has a cover by the designer Enid Marx.

Cover design by Enid Marx for Birds of the Sea (Penguin, 1945)

The one thing we haven’t included is a bird spotter’s guide – the sort of pocket-sized handbook that serious twitchers could take out on field trips. Although people can now carry guides to birds on their smart phones, many of these, both online and printed, still feature illustrations rather than photographs. Artists can ensure, in a way that a photographer often can’t, that all distinguishing features are clearly visible to help identification. Ornithology in the 21st century is still a science where amateurs make significant contributions to our knowledge.

Blog written by Patti Collins