- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

John Bradford

Last week we commemorated the death of Protestant martyr John Bradford on 1 July 1555, we thought this would be an excellent opportunity to go into more detail about this lesser-known Tudor martyr from Manchester. Bradford was born in Blackley and was educated at the Manchester Grammar School, going on to the Inns of Court, and then Cambridge. In 1550 he became an ordained priest and returned to the North West, going on to preach in churches in Lancashire and Cheshire.

Having initially begun a minor military career under the patronage of Sir John Exton in the 1540s, in 1547 Bradford had a change of heart, enrolling at Inner Temple. This career change coincided with Bradford’s conversion from Catholicism to Protestantism, having been influenced by the zeal of fellow reformers Thomas Sampson and Hugh Latimer. Bradford was ordained Deacon after his studies in Cambridge by Nicholas Ridley, the Bishop of London; Ridley also granted Bradford a preaching licence. Bradford then served as chaplain to Ridley until he became one of six chaplains in ordinary to King Edward VI. This appointment signalled Bradford’s high status in the protestant hierarchy. From 1552 Bradford began preaching in the North West of England whilst on leave from Court. In 1553 he would continue to preach his Protestant sermons under the reign of Mary I, who was in the process of returning the country to Catholicism.

Bradford was summoned to appear before the Queen’s Council at the Tower of London and was charged with sedition, remaining as a prisoner in the Tower before being moved to the King’s Bench Prison in March 1554. During his time in prison, he would continue to preach and would often disperse unrest amongst the other Protestant prisoners; he also composed various treatises in response to his Catholic rivals, among which were ‘To a Free Willer’ 1554 and ‘To Certain Free Willers’ in 1555.

As the Marian government intensified its prosecution of active Protestants, Bradford was examined on 29 January 1555 and proclaimed a heretic on the 30 January. He would be left in limbo for five months before his execution. This was due to his popularity amongst the Protestant population especially in the North of England. During this period the writ for his execution was withdrawn in February in the hope he would recant and convert to Catholicism, however Bradford continued to refuse. On 30 June 1555 he was returned to prison to await execution the next day. On the 1 July 1555 John Bradford was burned at the stake in Smithfield, along with John Leaf a younger Protestant prisoner. Bradford has been credited with the phrase ‘There but for the grace of God I go’

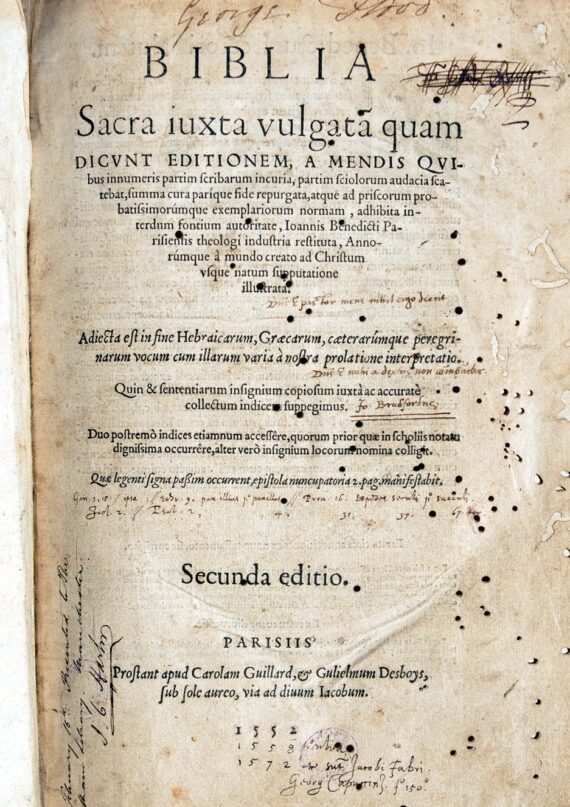

Above: Title page of Bradford’s Bible

Here at Chetham’s, we have some interesting items in our collection relating to John Bradford. For example, we have a bible that once belonged to him. The Bible is a quarto Vulgate, printed in Paris in 1552. As Bibles go, this is not particularly interesting or important, although has some rather attractive illustrations, not least some ninety-two woodcuts by Hans Holbein in the Old Testament. It might strike us as odd to find a Protestant reformer owning a Latin Bible, but the book is inscribed on the title page in Bradford’s neat and tiny hand and there are marginal notes by him throughout. The Bible was presented to Chetham’s in 1855 and has been used ever since as the Bible for all installations of the Bishops of Manchester.

In addition to the bible, we have one of the few existing portraits of the Manchester Martyr. Sadly the artist has not been identified. The painting was gifted to the library in 1684 by James Illingworth.

12 Comments

Clive O'Donnell

Fascinating article. When I read of these martyrs who had the opportunity to recant and refused, I am in awe of their faith and bravery.

ferguswilde

Thanks, Clive, their willingness to endure for their faith is remarkable indeed.

David Rayner

Thanks for this article. I’d never heard of John Bradford, so I particularly enjoyed learning about his local roots. I hope it’s not being pedantic to suggest that you correct an error. You say that Bradford was ordained deacon by Nicholas Ridley, Archbishop of London. Ridley was Bishop of London. I don’t think there’s ever been an Archdiocese of London

ferguswilde

Hi David, indeed, our bad, Ridley was Bishop of London indeed – and apparently the only holder of that office to be styled ‘Bishop of London and Westminster’. Amended accordingly. Ridley, of course, subsequently followed his own path to execution at Oxford in l555 after his support of the usurper Lady Jane Grey.

Gillian Hughes

I had not heard of Bradford previously, but was fascinated by his story–thank you!

ferguswilde

Thanks, Gillian, glad you found the post interesting!

David Ross

It would not have been at all odd for a protestant minister to have a Latin bible (and in fact the Book of Common Prayer was also in a Latin version). In universities Latin was known by all. So in those situations the use of Latin in worship did not go against the protestant wish to conduct public worship in a tongue understood by all.

As a Mancunian, born in Crumpsall, I welcome the attention given to a “local lad” who courageously died for his beliefs.

As a Catholic convert from Anglicanism I pray for the day when all will fully respect everyone’s right to follow, and to peacefully proclaim, their own beliefs. The horrendous deaths inflicted by burning protestants at the stake, and hanging, drawing and quartering catholics are a dreadful stain on our Christian history.

ferguswilde

Hi David, yes, the entire scholarly apparatus of the Bible in the Western church, in its pre-Reformation form and in its various denominations afterward, was in Latin as the international language of scholarship at the time, and the Jerome Vulgate was the Bible text all expected to see and work from. The Book of Common Prayer, after all, introduces each Psalm with its Latin incipit. John Bradford’s studies would be no exception. I think what we were trying to address is the surprise some are inclined to feel at seeing that his Bible isn’t in English, but your point certainly stands. The tragedy of the violence of those holding one belief against those holding another is certainly a terrible stain, and the sixteenth century perhaps the very model of how not to live a Christian life. We can remember the martyrs on both ‘sides’ of the Reformation for their bravery, and hope fervently that these inhumanities can be consigned to the past. Thanks for your thoughthful remarks.

Rodney Bowers

Did John Bradford have children. Seems I saw where they fled to Scotland after his execution.

ferguswilde

Thanks Rodney – according to the Dictionary of National Biography, “He never married, but as far as possible remained on affectionate terms with members of his family.”, and it doesn’t record any children born outside wedlock, so it seems not.

Mick Fanning

I fully enjoyed reading this very interesting piece on the Manchester Martyr and look forward to look forward to any future pieces regarding any historical Mancuncian figures.

Many thanks

Mick

Michael Woolf

A very interesting piece.