- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

John Dee and Alchemy

When John Dee initially sought appointment as the warden of a collegiate church following his travels on the continent, Manchester was far from his mind. Instead, he had fixed his hopes on the wardenship of the Hospital of St Cross in Winchester, or else the provostship of Eton College or the mastership of Sherborne School. Among the reasons that he listed for preferring the wardenship of St Cross above all other appointments was its ease of access to glass-blowers in the south of England, which would have enabled him to personally oversee the production of glass instruments, and the space afforded by the hospital buildings for the establishment of a printing workshop and what would now be called a ‘research institute’ to advise the royal court. It seems likely, given his mention of such glass instruments, that Dee’s proposed research included alchemy.

The practice of alchemy, ‘a form of speculative thought that, among other aims, tried to transform base metals such as lead or copper into silver or gold and to discover a cure for disease and a way of extending life’, fascinated scientists for centuries. First practiced in Hellenic and Greco-Roman Egypt during the classical period, interest in alchemy was revived in the West following the translation of lost Greek scientific and medical texts from Arabic (in which they had been preserved) into Latin during the twelfth century and their re-introduction into the Western textual canon. Even the practice’s name reflects its route of transmission, since the word ‘alchemy’ descends from the Arabic word ‘al-kīmiyā’, meaning ‘the Egyptian [science]’. Alchemy remained a common preoccupation in medieval Europe, reflected in surviving alchemical manuscripts such as the famous Ripley Scrolls, a family of parchment scrolls that display learnedly-obscure mystical imagery, the meaning of which is not fully understood even today.

Figure 1: Hermes Trismegistus, the purported founder of alchemy, holding a large vessel known as a Hermetic Vase in a sixteenth-century ‘Ripley Scroll’ (San Marino, Huntington Library, HM 30313).

The appeal of alchemy persisted during the early modern period, and the practice was adopted by those who, in subsequent centuries, would come to be described as scientists: the modern word ‘chemistry’ shares its etymology with ‘alchemy’, and the first recorded instances of the terms ‘research’ and ‘researcher’ in a scientific sense in English both occur in an alchemical context (albeit after Dee’s lifetime). Even the renowned scientist Isaac Newton (1643–1727) is known to have taken an interest in alchemy alongside his more famous scientific pursuits; indeed, the two were very closely entwined for him. Besides the more famous goals of transmuting base metals into precious ones and discovering the philosopher’s stone, the art of alchemy also extended to practices that might today be termed ‘chemical technology’, such as the production of pigments and salts, the refinement of ores, the manufacture of acids and the distillation of alcohol, and to medicine, pursuits that were all linked by their experimental approach.

John Dee was arguably Britain’s most famous alchemist, and his interest in the subject was reflected in his personal library, which was one of the largest in sixteenth-century England. His collection included a large number of books about alchemy, many of which can now be found in the library of the Royal College of Physicians, which contains more than one hundred books from Dee’s library. Nor was Dee’s engagement with alchemy purely theoretical: he constructed alchemical laboratories at his home of Mortlake, and in 1571, he travelled to the Duchy of Lorraine (present-day Lorraine in France) to acquire and bring back ‘a great cartload of specially made vessels’ for these laboratories. As was seen, he also hoped to supervise the production of glass instruments from the Hospital of St Cross.

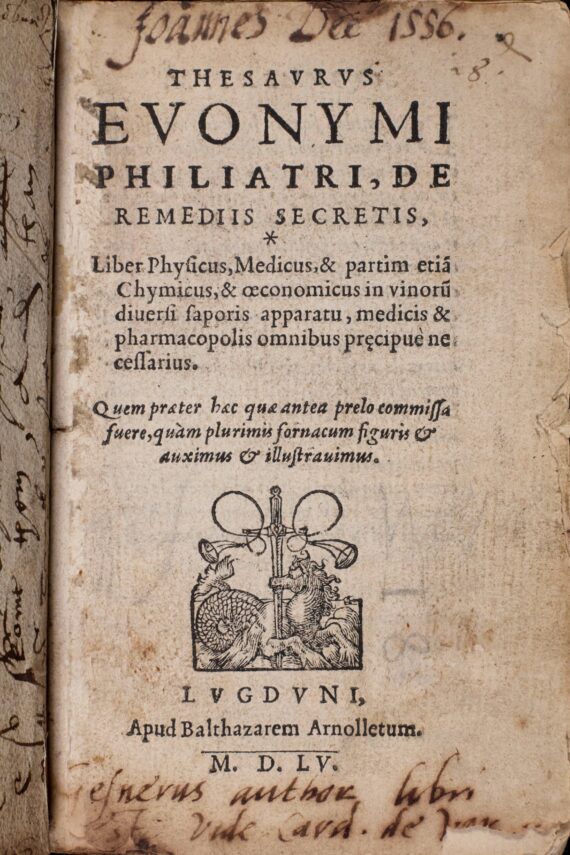

Figure 2: The title page of John Dee’s copy of Konrad Gesner’s De remediis secretis (Lyon, 1555) (Chetham’s Library, Mun. 7.C.4.214).

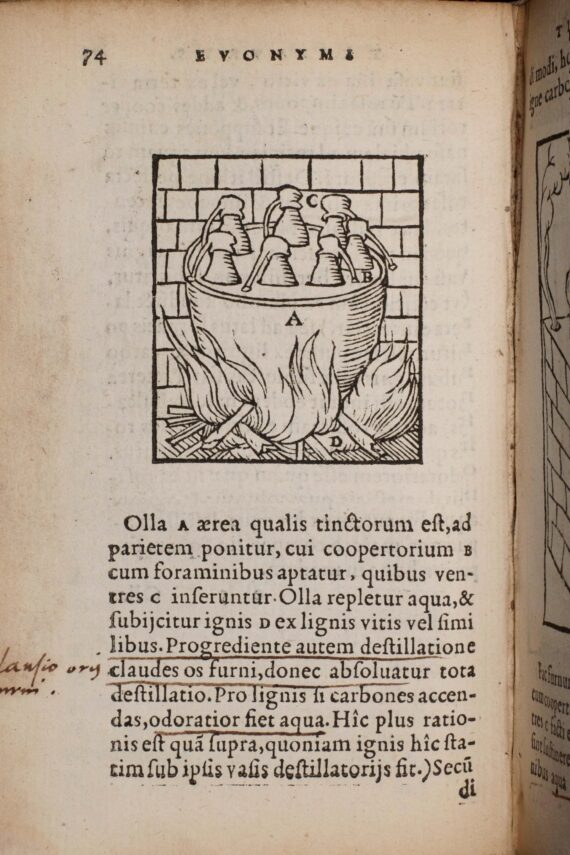

Figure 3: A depiction of a furnace in Konrad Gesner’s De remediis secretis (Chetham’s Library, Mun. 7.C.4.214, p. 74).

Fortunately, Dee’s own handwritten catalogue of his library survives, and is preserved in the library of Trinity College, Cambridge. This catalogue can be viewed online, while the an edition of the catalogue was published by the Bibliographical Society in 1990. Meanwhile, a search for ‘alchemy’ in Chetham’s Library’s catalogue of printed books returns sixty-seven results, forty-seven of which relate to books published between 1500 and 1699. Cross-referencing these two catalogues enables us to identify three books that Dee is known to have possessed copies of that can also be found in our collections. One of these alchemy books actually belonged to Dee himself, a copy of Konrad Gesner’s De Remediis Secretis, published psuedonymously in Lyon in 1555. This work was primarily concerned with the art of distillation and its use in medicine, and it contains illustrations depicting furnaces, glassware and other equipment used in the distillation process. Chetham’s Library’s copy of this book contains extensive manuscript annotations, underlining and even small drawings, most of which were made by Dee himself.

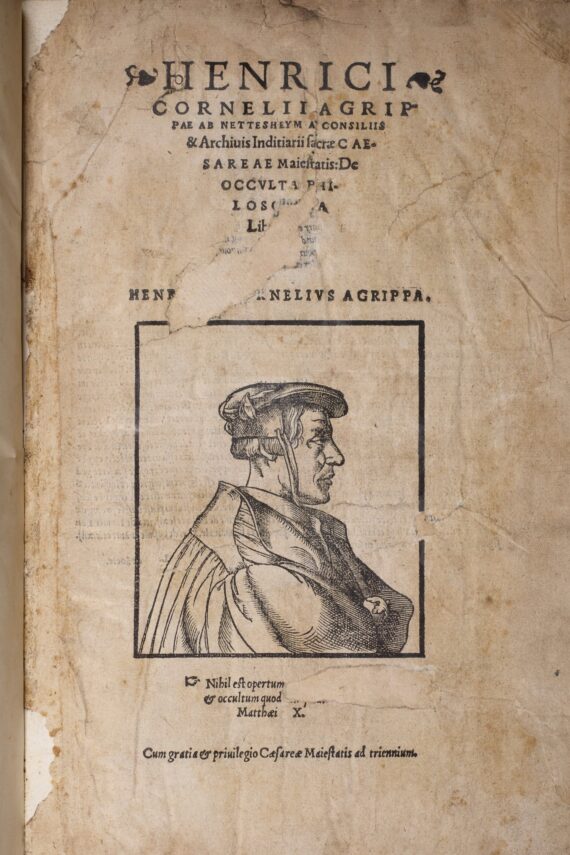

Figure 4: The title page of Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim’s De occulta philosophia (Basel or Cologne, 1533) (Chetham’s Library, 2.I.5.32).

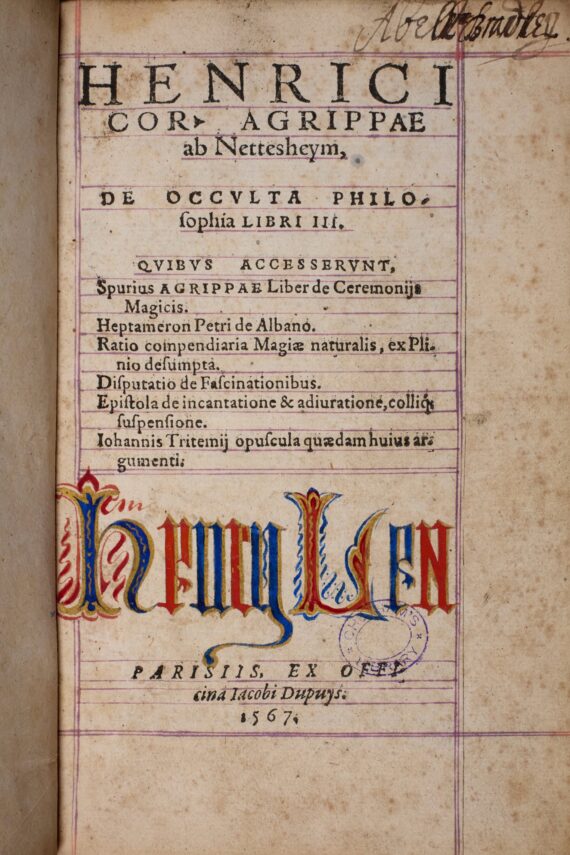

Figure 5: The title page of Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim’s De occulta philosophia (Paris, 1567) (Chetham’s Library, 3.A.2.28).

Another book that Dee is known to have owned a copy of was Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim’s De occulta philosophia. Von Nettesheim was a physician, legal scholar, soldier, theologian, occult writer, and court historiographer to the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. He was born in Cologne and studied and taught at the university there, before travelling widely and lecturing in theology at various universities. He may also have founded a secret society devoted to magic, astrology and the Kabbalah, and, like Dee, he has since been compared to the literary Dr Faustus, who made a pact with the devil in order to obtain knowledge, wealth and power. The De occulta philosophia was divided into three parts concerning the natural world, the celestial world, and the divine world. In it, Von Nettesheim explained the philosophy and methods of magic, alchemy and astrology, and provided examples, illustrations, diagrams and techniques. He drew information from classical, medieval, and renaissance sources, and synthesised them into ‘a coherent explanation of the magical world’ in accordance with the Christian faith (although the work still faced censure from the Inquisition). Chetham’s Library possesses two editions of this book that were published during Dee’s lifetime: one that was published in Basel or Cologne in 1533, and another that was published in Paris in 1567. More recently, the publisher Inner Traditions released a modern hardback edition of Von Nettesheim’s book, which the publishers Simon & Schuster described as ‘one of the most important texts in the Western magical tradition for nearly 500 years’. The book was priced at no less than £170!

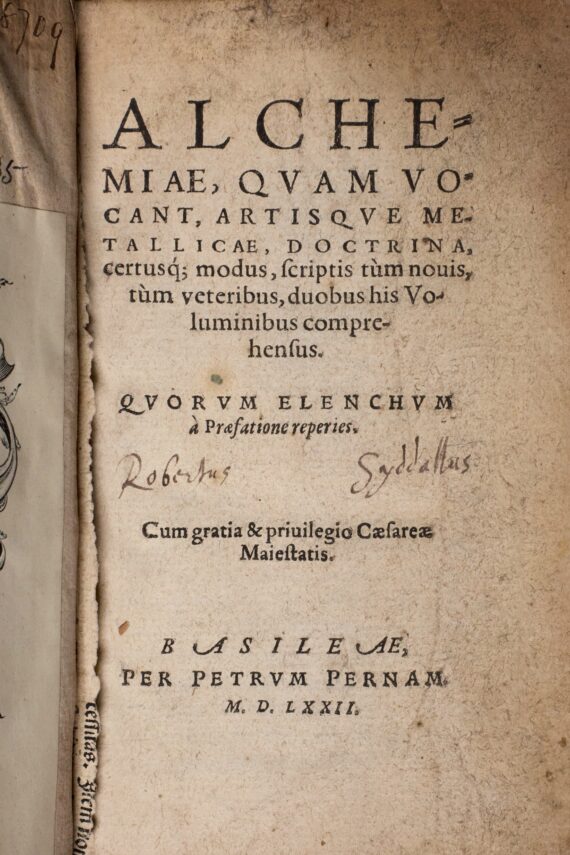

Figure 6: Title page of Guglielmo Gratarolo’s Alchemiae quam vocant (Basel, 1572) (Chetham’s Library, 3.E.3.36).

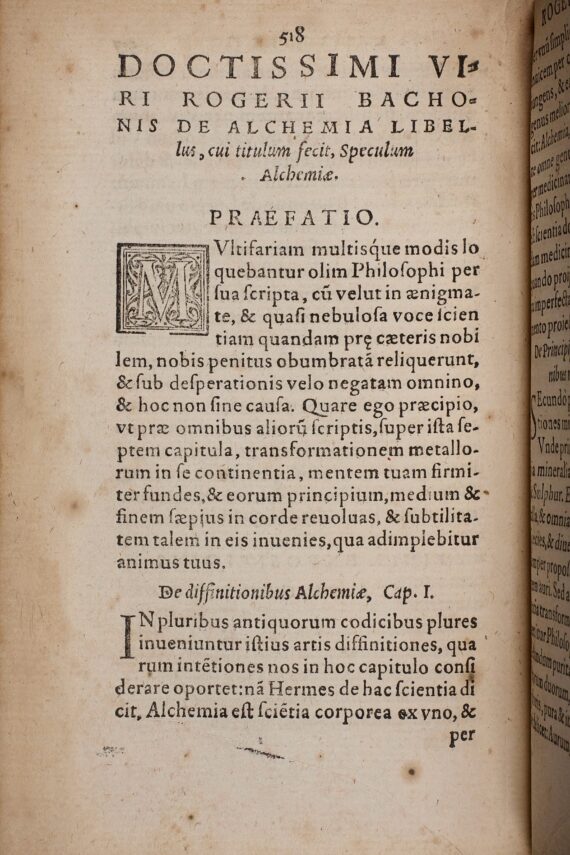

Figure 7: A text attributed to Roger Bacon in the Alchemiae quam vocant (Chetham’s Library, 3.E.3.36, p. 518).

A third book that Dee is known to have owned a copy of was known by an exceptionally long title, Alchemiae, quam vocant, artisque metallicae, doctrina, certusque modus, scriptis tum nouis, tum veteribus, duobus his voluminibus comprehensus (‘The doctrine and certain manner of alchemy, as they call it, or the art of metals, in both new writings and old, contained in these two volumes’). This book was edited and published by Guglielmo Gratarolo, a physician and alchemist from a wealthy Italian family who studied at Padua and Venice. As a Calvinist, he was forced to flee Italy and sought refuge in Graubünden, Strasbourg and finally Basel, where he taught medicine and edited texts on a wide range of subjects, including medicine, dietetics, memory, wine, agriculture, and alchemy. It was there that Chetham’s Library’s copy of the Alchemiae quam vocant was printed in 1572. In the preface to this work, Gratarolo announced his intention of editing and publishing new and existing alchemical texts for a new generation of scholars, while correcting the obscure passages in them to make them easier for readers to understand. At a time when out-of-print texts were much harder to access than they are today, this must have been an invaluable book for any aspiring alchemist to possess. Chetham’s Library’s collections also contain two more books about alchemy that were edited by Gratarolo: Johannes de Rupescissa’s De consideratione quintae essentiae rerum omnium (Basel, 1597), and Giovanni Braccesco’s De alchemia (Hamburg, 1673).

Despite his strongly-expressed preference for the wardenship of St Cross, Dee was appointed as the warden of Christ’s College in Manchester and installed in February 1596. As was seen in a recent blog post, the college’s affairs were in a disordered state, and his attempts to resolve them brought him into conflict with the fellows. He nevertheless found some time to pursue his interest in alchemy while he was in Manchester, although his plans for a research institute never came to fruition. Another of Dee’s unrealised proposals was the foundation of a national library, and while his period in Manchester came half a century before Humphrey Chetham left money for the creation of a public library in the town, it is almost certain that he would have thoroughly approved of the project. Indeed, it is probably the case that he would have been much happier if he had come to Manchester as a librarian, rather than as the warden of a college of priests!

Blog post by Patti Collins