- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

KEEP IT SECRET, KEEP IT SAFE: WAX SEALS AND LETTER-LOCKING

As anyone who has visited recently will know, Chetham’s Library played host this summer to a remarkable assembly of furniture: the original marriage bed of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, a copy of it produced by the prolific Victorian forger George Shaw, and several other pieces of furniture produced by him and passed off as original Tudor pieces. The story of the marriage bed’s rediscovery and its connection to Chetham’s Library is a thrilling one, and it has been a pleasure sharing it with so many of you through tours and evening lectures during its time here. Now that the furniture has been safely packed away, however, our thoughts have turned to the new exhibition that has taken its place in the library, which focuses on the fascinating hidden history of ciphers and codebreaking.

For as long as written communication has existed, people have had to contend with the fact that others might try to intercept and read their missives, and have consequently gone to great lengths to prevent this. Codes and ciphers have long been employed to encrypt the contents of letters, preventing anyone who did not have the key from reading them. Several books in our collections deal with precisely this topic, providing instruction on how to create substitution ciphers that replaced the letters of the alphabet with other letters or symbols. Such ciphers eventually developed into modern cryptography, including the Enigma Code that was employed by Germany during the Second World War. In fact, one of our past Assistant Librarians, Pauline Leech, worked as a codebreaker in Hut 6 at Bletchley Park, where Enigma was cracked, before she came to the library!

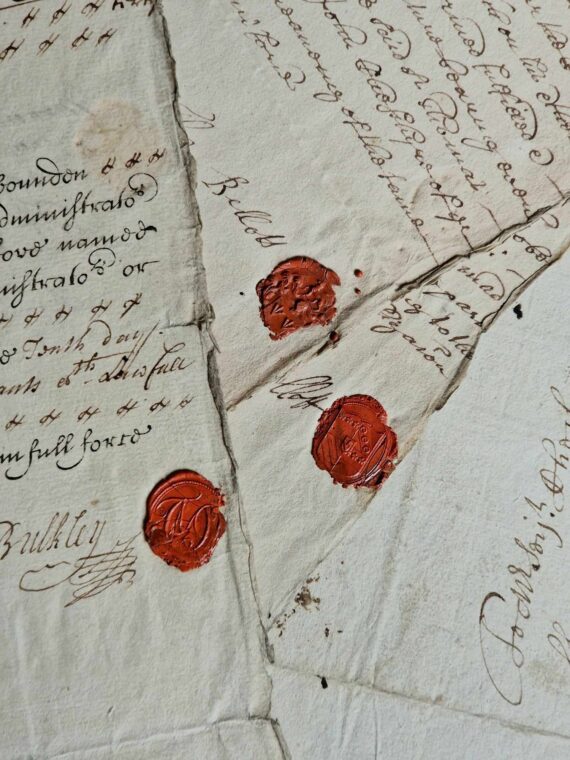

Wax seals on letters in our collections (Chetham’s Library, E.1.4/5, A8, 14, 21 and C13).

Another way of keeping the contents of a letter safe was to ensure that nobody could open it without it being obvious that they had done so. Since ancient times, wax seals were used to close letters; each seal was unique to its owner, so an intact seal signified both that the letter was genuine, and that the letter’s contents had remained private. The Romans used rings engraved with images, sometimes carved into gemstones called ‘intaglios’, to make their impressions in the wax. During the medieval period, these intaglios were sometimes reused and set into rings that bore legends attesting to the secrecy of their messages: examples include ‘clausa secreta tego’ (‘I cover closed secrets’), ‘frange, lege, lecta tege’ (‘break, read, cover what is read’) and ‘tecta lege, lecta tege’ (‘read what is covered, cover what is read’). The use of seals persisted well into the early modern and modern periods, and several letters in our collections still bear the traces of the seals that once kept them secure.

The Chetham seal matrix (Chetham’s Library, no shelfmark).

A particularly exciting item in our collections, and one that was only acquired recently (through the generous assistance of the Friends of the Nation’s Libraries), is a seal matrix with three faces. The matrix was therefore capable of making three different impressions in the wax, depending on which face was used. At the moment, we don’t know much about who originally owned this matrix, but it clearly has a connection with either Humphrey Chetham or the library that he founded, since the Chetham achievement of arms is found on one of its three faces: the crest (a demi-griffin gules charged with a cross double-crossed, or) above the eschuton (quarterly, 1st & 4th, argent, a griffin segreant gules, within a bordure, sable, bezantée; 2nd, argent, a chevron between three crampons, gules; 3rd, gules, a cross double-crossed, or; over all charged with a crescent for difference). On the second face, the Chetham griffin crest – the symbol still used by the library to this day – is displayed on its own. On the third face, an as-yet-unidentified classical head appears in profile.

Nevertheless, letters closed by wax seals weren’t as secure as might be imagined. Using a heated knife, someone determined to read a letter’s contents could have lifted its seal intact before reapplying it with an extra dab of wax, leaving next to no trace that it had ever been opened. As a result, during the early modern period – when easily-foldable paper replaced stiff parchment as the most commonly-used writing support – people started to come up with more and more inventive folding techniques that added yet another layer of security to letters. Some, such as the ‘tuck and seal’, were relatively simple, while others, such as the ‘spiral lock’, were incredibly complicated and, as a result, incredibly secure. The former is known to have been used by Elizabeth I’s chief adviser William Cecil, and the latter by Elizabeth herself, so it is entirely possible that John Dee received letters locked in this way while he was the warden of Manchester’s collegiate church between 1595 and 1608/9. In fact, all letters sent before the invention of the envelope in 1840 were closed by folding them in some way, since the early postal service charged by weight rather than size; folding letters enabled senders to avoid using a second sheet of paper as an envelope, which would have doubled the price!

Modern reproductions of locked letters.

Common to both wax seals and letter-locking is the fact these were highly personal ways of securing correspondence. The poet John Donne, whose literary works we have in our collections, even developed his own unique letter-lock, which perhaps provided an extra layer of security! Other encryption techniques were less personal, however, and we’ll be taking a look at those in future blog posts relating to our new exhibition. We’ll also be exploring Pauline Leech’s experiences of Bletchley Park and the library through her diaries, also in our collections. We hope you’ll enjoy coming with us on this journey into the hidden history of correspondence! To find out more about the fascinating practice of letter-locking, you can visit the Letterlocking project page here.

By Emma Nelson

1 Comment

Judith Redfern

MANY years ago, when we sent a registered parcel. It was tied up with brown paper and string and with a blue crayon you made a cross completely encircling the parcel. The string was crossed and after the parcel tag attached, red sealing wax was used on various points of the string, pressing onto the paper. I quite liked the aroma of the wax but did burn my fingers a time or two LOL