- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Morbid Curiosities: Gothic Stories In The Library

If you have been on a tour of Chetham’s Library before, you might have heard that the cabinet at the end of the Library’s Mary Wing used to contain a real human skeleton, rather than the books that now occupy it. To the modern mind, a skeleton seems like a fairly strange thing to find in a library, but libraries in the early modern period – besides keeping books – fulfilled a similar function to museums today, displaying ‘curios’ to excite the interest of visitors. Chetham’s Library was no exception, and our collections once included a variety of curiosities – some of them morbid, such as the hand of a mummy from Thebes – which were shown off to visitors by boys from Chetham’s hospital school. In the same spirit, and in conjunction with our new ‘morbid curiosities’ tour, we’ve gone in search of sinister stories from the archives to share with you.

Fig 1: The death mask of Thomas Whitaker in the library.

For almost all of recorded history, people have been fascinated by death. The famous expression ‘memento mori’ (‘remember that you must die’) originated in the ancient world and has persisted ever since, although its meaning has changed during that time. Initially intended as a reminder to enjoy life’s pleasures (as in the phrase ‘eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we die’), it took on a more sombre tone in the medieval and early modern periods, and instead reminded the recipient to live a godly life to secure a place in heaven. ‘Memento mori’ jewellery incorporating skeletal imagery came into fashion in the fifteenth century, and developed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries into mourning jewellery commemorating specific individuals’ deaths. It was in the nineteenth century, though, that this morbid preoccupation reached startling new heights. This period witnessed extremely high mortality, and reminders of that were very much in-vogue; photographic portraits were made of the recently-deceased, plaster death masks were taken from them (including a death mask of Thomas Whitaker in the Library), and mourning jewellery was made from their hair.

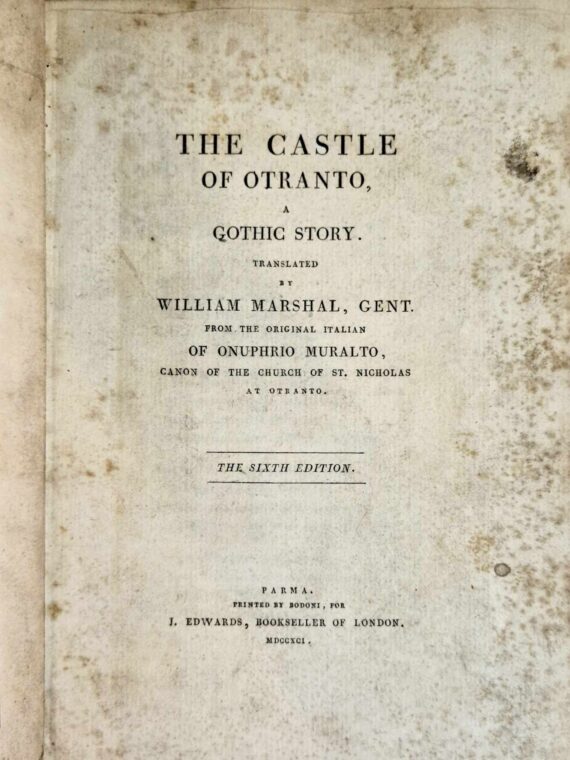

Fig 2: The Castle of Otranto (1764).

Unsurprisingly, this fascination with death extended to literature as well, with the development of the new ‘gothic’ genre characterised by its focus on horror, haunting, the unnatural and the supernatural. These elements had existed in storytelling for centuries; ghost stories have survived from the ancient world and the medieval period, and Shakespeare’s plays utilised ghosts, omens and the supernatural as narrative devices in ways that notably foreshadowed the genre’s development. It was in the second half of the eighteenth century that the genre truly took shape, though. Our collections include a copy of The Castle of Otranto (1764), a work widely regarded as the first gothic novel and described as such from its second edition onwards. The novel’s narrative revolves around the inheritance of a southern-Italian castle, and features paintings that seem to move, doors that close by themselves, and skeletal and ghostly apparitions. Originally passed off as a genuine translation from an Italian manuscript, the work was a success and spawned various imitators in the years that followed. This early popularity of the genre is reflected in another gothic novel found in our collections, Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey (written 1803, first published 1818), which subverted the genre’s expectations through a heroine who avidly devours gothic fiction but foolishly mistakes it for real life.

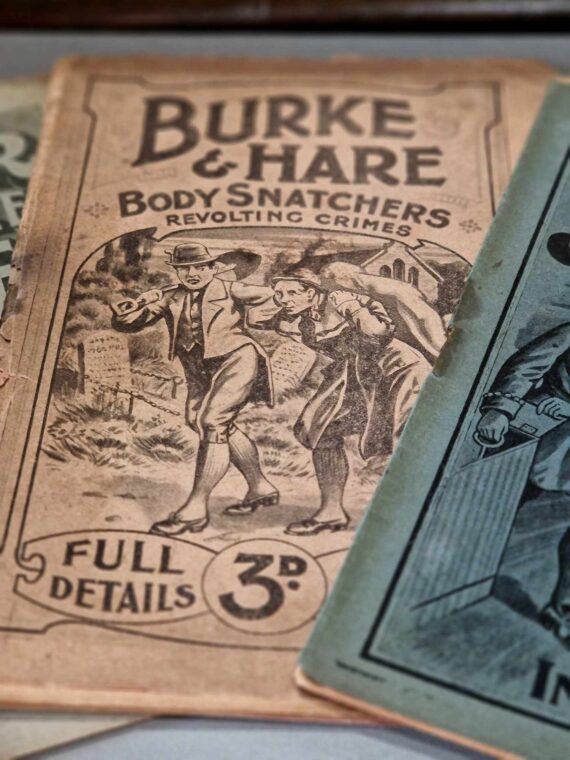

Fig 3: The ‘penny dreadfuls’.

The nineteenth century saw the flourishing of the gothic genre, and the circulation of gothic fiction in increasingly accessible format. This phenomenon is best exemplified by the so-called ‘penny dreadfuls’, which, as their name suggests, were morbid stories sold for a penny apiece. Published weekly from the 1830s onwards, these cheaply produced booklets featured sensational narratives of body snatchers, murderers and highwaymen. They were wildly popular, especially among the working classes, and even poor working-class boys who couldn’t afford the penny a week to purchase them would form clubs, splitting the cost of the booklet and passing it from reader to reader. Despite their seemingly humble format (and perhaps on account of their broad appeal), some of the serial stories published in penny dreadfuls even shaped gothic fiction as a genre. Varney the Vampire (1845-7) introduced many of the most recognisable stylistic cues of the subgenre of ‘vampire fiction’, and paved the way for one of the most famous gothic novels ever written, Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897). Another serial story, The String of Pearls (1846-7), introduced the famous character of Sweeney Todd, the demon barber of Fleet Street who murdered his customers and sold their bodies to make pies.

Fig 4: An illustration of Marley’s ghost from A Christmas Carol (1843).

Of course, no discussion of gothic fiction would be complete without mentioning the Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol (1843). Written and published in a hurry following the failure of Dickens’ previous serial story, Martin Chuzzlewit (1833-4), the new novel was an immediate success, selling out of its first print run in only four days. Its narrative reflects Dickens’ horror at the real conditions of working-class children, but its supernatural elements place it firmly within the gothic genre; Dickens described it as a ‘’ghostly little book’, and Scrooge’s remarkable transformation from a miserly old man into a kind, generous one, following ghostly intervention and premonition, perfectly reflects the medieval and early modern reforming tradition of the ‘memento mori’ expression. It also establishes a connection between long winter nights and morbid tales.

By Emma Nelson.

4 Comments

Dianne Mitchell

I wondered whether the morbid curiosity talk would be repeated this year as I wasn’t aware of it.

Also other events for 2024 as we would be interested in attending. I have been on the library tour which I found really interesting.

ferguswilde

Thanks, Dianne! Glad you found the tour interesting, we do our best! Please take a look at https://library.chethams.com/whats-on/ from time to time to see what we’re doing next, and you could also subscribe to the library newsletter, where we will advertise upcoming events. We’d be very glad to see you there! There’s a newsletter sign-up form at the foot of that page, and on the home page at library.chethams.com. It’s a low-volume list, so you needn’t fear us filling up your inbox.

Kevin Edwards

Articles like this really add another dimension to the library and improve my understanding of it.

ferguswilde

Thanks, Kevin! Glad to hear you liked it and found it informative. We’ll do our best to keep that up.