- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

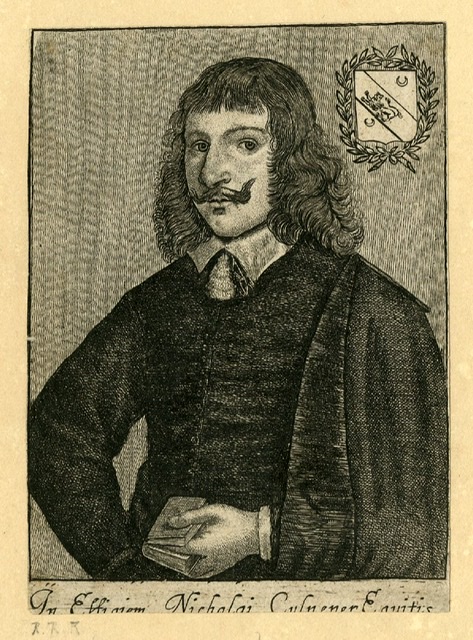

Nicholas Culpeper

As our most recent theme for our display and guided tours is based on herbs and remedies, we thought we would focus this blog on the same topic. One of the most famous exponents of herbal treatments was Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654), a renowned herbalist and astrologer who was practising at a complex time in the history and development of medical and pharmaceutical practice. In sixteenth-century England the medical profession Culpeper was unregulated, which meant that apothecaries and physicians frequently worked without proper training or knowledge, often doing more harm than good. As a remedy for the baleful effects of ignorance or even malpractice, leading physicians of the time desired the ability to award licences to those who met certain standards they would define, and to punish and disbar the incompetent. Members of this group, the most prominent of whom was Thomas Linacre (1460-1524), petitioned Henry VIII on the matter in 1518. The result was the creation of the Royal College of Physicians, who became the regulatory body for medical practice.

The College’s power extended to regulating the trading of apothecaries, who needed to procure a legal licence to carry out medical treatment if working within seven miles of London. Further restrictions were promulgated under James I, when all physicians were required by royal proclamation to possess and consult the Pharmacopoeia Londinensis or ‘London Dispensatory’. The Pharmacopeia was printed in Latin; most medical practitioners had only basic ability in the Latin language, and the text itself gave only limited recipes, rather than actual surgical or medical advice. The restriction also meant that the Royal College of Physicians were able to create an approved list of all known medicines, their effects, and usage. It was illegal to concoct any medicine or sell any remedy if it did not appear in the Pharmacopoeia Londinensis.

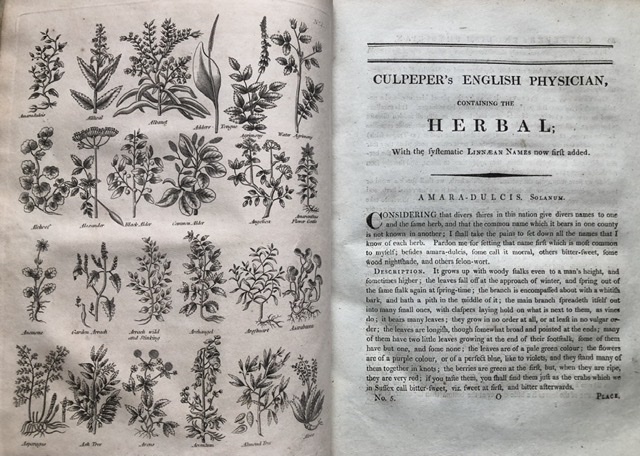

Our copy of Culpeper’s English Physician.

Nicholas Culpeper was born on the 18th October 1616 in Surrey. His father died shortly before his birth, so his mother returned with him to her father’s home in Sussex. The Culpeper family was wealthy and well-established: it owned Leeds Castle in Kent and had ties to Catherine Howard (the ill-fated fifth wife of Henry VIII) and her reputed lover Thomas Culpeper, former courtier, and gentleman to the King’s Privy Chamber.

Culpeper was not to benefit from these family ties as he was raised by his grandfather on his mother’s side, William Attersole, a rector who hoped his grandson would follow him into holy orders. However, Nicholas was more inclined toward the study of physic, astrology, and the occult. He would go on to be apprenticed to various apothecaries, settling into work for a Samuel Leadbetter in London. In 1640, he married a wealthy woman named Alice Field and established a home in London. The Leadbetter apothecary practice was subject to the Royal College of Physician’s restrictions as it fell within the 7-mile radius of its power and would come into conflict with them frequently.

By the mid-1640s, Culpeper had established his own pharmacy at his home in Spitalfields, outside the authority of the City of London. Culpeper was extremely professionally active, sometimes seeing as many as 40 patients in a morning, using his medical experience and astrology and devoting himself to using herbs to treat his patients, while providing his services and cures free of charge. He was a radical in his time, and was even accused of witchcraft in the early years of the Civil War. Culpeper often came into conflict with other apothecaries and physicians because he condemned their greed and their use of harmful practices such as bloodletting. He also caused dissent by offering much cheaper herbal alternatives to the costly concoctions of others.

In the 1650s he went further and translated Latin medical texts such as the Pharmacopoeia Londinensis into English. His most famous work is The English Physician, or Complete Herbal, which is still in print today. Published in 1652 the text was deliberately sold cheaply to encourage purchases among the poorest of society and was an attempt to combine astrology with herbal medicine, as well as to provide a translation of Latin texts of descriptions of plants and their medical uses. The Royal College of Physicians was unable to censor the work due to the upheaval of the Civil War.

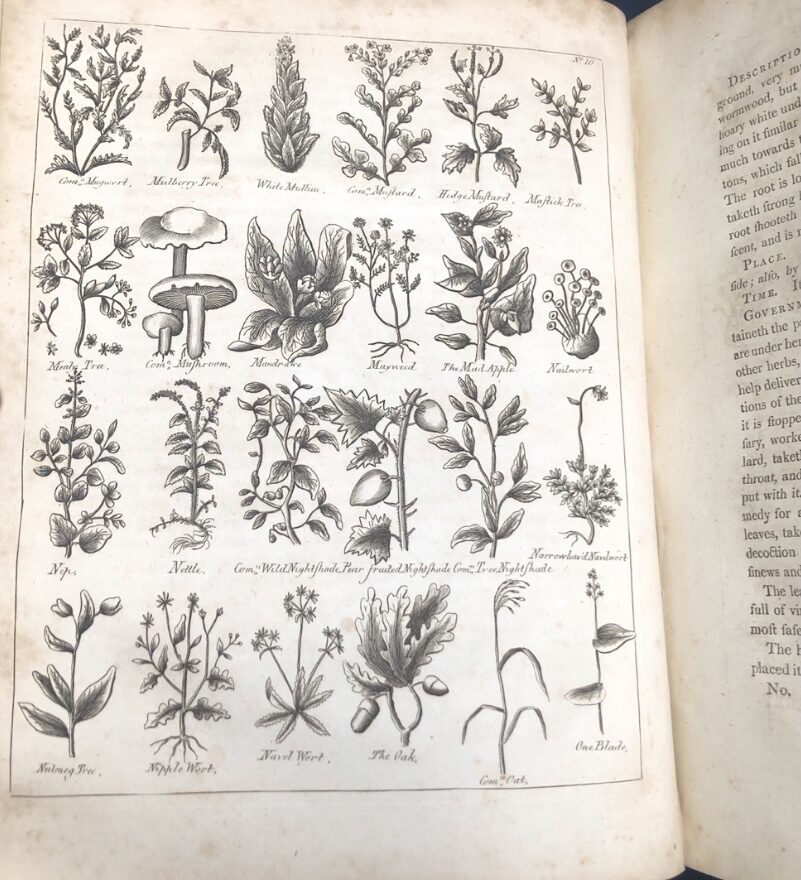

Some of the herbs Culpeper identifies.

Culpeper was also a strong advocate for a republic rather than a monarchy, and predicted the demise of the monarchy across Europe in his posthumously published Ephemeris of 1655. These beliefs were reflected in his decision to fight with the Parliamentarians. He joined the London Trained Bands in August 1643 under the command of Philip Skippon and fought at the First Battle of Newbury, where he carried out battlefield surgery. Whilst with the Bands he suffered a chest wound from a musket ball, which would continue to plague him. He died at the age of 38 in January 1654 from consumption, a condition most likely aggravated by the wound.

Further works building on his notes and trading on his fame were published posthumously, including Astrological Judgement of Diseases from the Decumbiture of the Sick (in 1655), and A Treatise on Aurum Potabile in 1656. Culpeper’s translations and approach to using herbals have had an extensive impact on both traditional, holistic, and modern medicine, as can be seen by the fact that the English Physician is still in publication, giving it one of the longest continuous print runs of any English language book.

More of Culpeper’s illustrations.

Chetham’s Library, founded in the will of Humphrey Chetham at his death in 1653, was being actively formed by his executors in the year of Culpeper’s death, 1654. His posthumous works were already being prepared for the press; when the Astrological Judgement appeared in 1655, our doors were opening for the first time to provide free access to knowledge. So far, the judgement of history seems to be that both he and we still have things to offer the present.