- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Poetry in the Margins

Poetry in the Margins: A Marian Missal Annotated by Lawrence Langley

We’re delighted to be able to publish a first post here by Ellen Werner, who has joined us to undertake her PhD under the AHRC Collaborative Doctoral Programme, supervised by Prof Sasha Handley and Dr Fred Schurink of the University of Manchester. Her project title is Early Modern Cultures of Reading in North-West England:

Chetham’s is home to many books with manuscript annotations, but perhaps few as painstakingly crafted as those left by Lawrence Langley in his copy of Bernardino de’ Busti’s Latin Mariale. Printed in Haguenau in 1513, the work discusses Marian devotion and the question of the Virgin Mary’s immaculate conception – an issue hotly debated in the Renaissance. Chetham’s acquired its copy in 1667, after it had already passed through the hands of several previous owners.

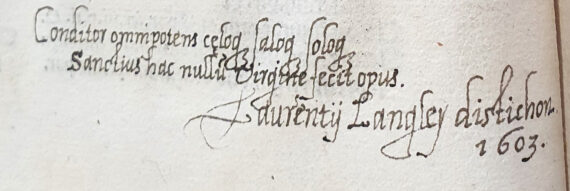

Among them was Lawrence Langley, whose signature appears a number of times throughout the text, with the first signature located at the end of the tabula or table of contents at the beginning of the book. Langley signed his name in a beautiful italic hand and dated his note to 1603. This date indicates that the annotator could be identical with a Lawrence Langleye of Lancaster who matriculated from Brasenose College Oxford in 1588 and was born in around 1570.

Langley’s signature on the last page of the tabula, fol. B5v.

Langley’s annotations are a fascinating insight into the way this early modern reader absorbed his books. The vast majority of Langley’s notes are in Latin, with the exception of the title page, where he translates the book’s full Latin title into English, and only one other note, similarly translating a passage from the printed text.

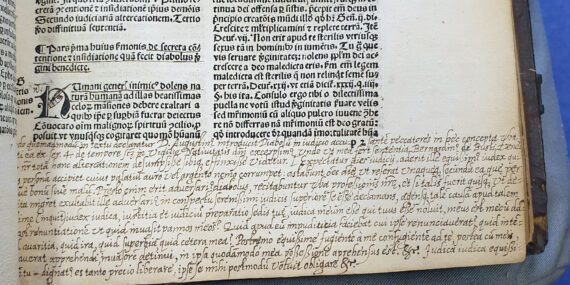

Some of his notes are clearly functional, such as folio numbers added by hand, pointing hands (‘manicules’) indicating important passages, summaries in the margins, additions to the tabula or cross-references to other authorities on the subject. In such annotations, Langley uses a large number of abbreviations to keep his annotations short in the cramped space of the margins and only gives crucial information, such as author and chapter of a text to which he is making a reference.

In other annotations, Langley brings together the views of several scholars, almost conducting a scholarly debate in the margins and often adding his own viewpoint. Such passages are typically lengthy and indicate Langley’s learning and familiarity with other written works on the subject, as well as an ability to consider a question from different perspectives and to draw his own conclusions based on existing works by other scholars.

Annotation by Langley drawing on other authors, here e.g. St Augustine. Note also the pointing hand added to the printed initial H, fol. 106r.

There are some notes, however, in which Langley shows us a more personal side, giving his opinion on passages that he considers particularly well expressed. One such annotation, for instance, reads […] prosopopoeia elegans face[t]ia, iucunda, predicanda. LL. (“[…] an elegant, rather fine, pleasant personification worthy of praise. LL.”). That Langley signs this note with his initials, something he never does with his more practical notes, reinforces the personal nature of this annotation: a 17th-century reader is here recording his enjoyment of a passage in the book he is reading.

Langley’s most unusual notes, however, are eleven Latin epigrams summarising individual passages in the book. These short poems, interspersed throughout the Mariale, display careful, beautiful penmanship, with far fewer abbreviations than Langley’s cross-reference notes. Each epigram consists of one hexameter and one pentameter, conforming to the metrical rules of classical Latin poetry. The epigram, a form of poetry originating from short inscriptions in verse, for instance on funeral steles, in ancient Greece, was later frequently used for satirical poetry, to which it was particularly suited because of its short, pointed nature. It became highly popular during the Elizabethan era as a kind of poetry on which students of Latin practiced their grammar and metrical skills. For people who, like Langley, had received an education in Latin, the composition of epigrams would therefore have been a familiar process.

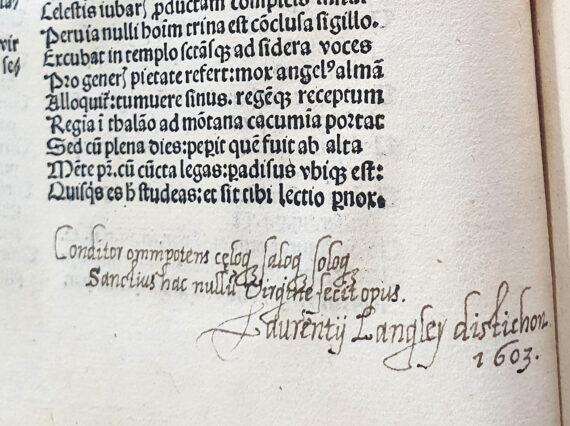

Langley’s first epigram in the Mariale can be found above his signature at the end of the tabula. It reads

Conditor omnipotens caeloq[ue] saloq[ue] soloq[ue]Sanctius hac nullu[m] virgine fecit opus.

[The creator, almighty in heaven, on sea and on earthMade no holier work than this virgin.]

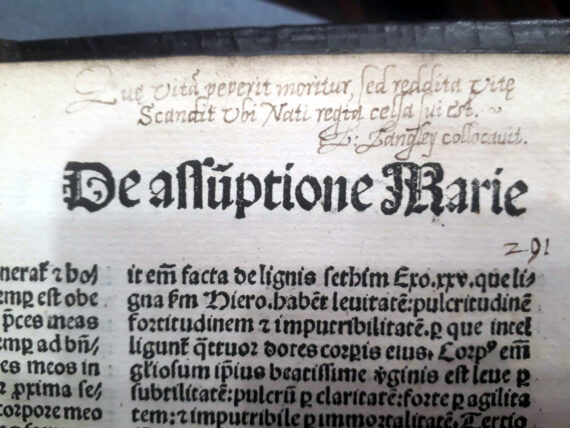

Not only does Langley adhere perfectly to the rules of Latin scansion, but he also signs the poem with the words Laurentij Langley distichon (“a distich by Laurence Langley”), demonstrating that his choice of the two-line (‘distich’) form was a conscious one. The other epigrams are generally signed with a similar awareness of himself as an author. On fol. 186r, for instance, Langley inserts an epigram about St Elisabeth and signs it L. Langley scripsit. (“L. Langley wrote this.”). On 291r, he marks an epigram on the Ascension of the virgin Mary with the words L. Langley collocavit. (“L. Langley put this down.”). Langley’s signatures and the vocabulary of writing he employs here designate him as an active co-creator of this copy of the Mariale: what de’ Busti writes, Langley expands on, adding poetry to a work of theology and demonstrating a sense of both literary and visual artistry, his calligraphy and metres equally finely crafted.

Epigram by Langley on the Ascension, fol. 291r.

Three other books with annotations by Langley are known to exist, two in the John Ryland’s Library (take a look at one of them here) and one in Trinity College Cambridge. It is likely, however, that there are more in other libraries – if you have ever come across Lawrence Langley and his beautiful annotations, let us know!