- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Richard Johnson, the First Librarian: No Surplus Surplice?

Richard Johnson is said to have been Chetham’s very first librarian, but his back story and relationship with Humphrey Chetham is better documented than his time in that post. His life spanned the first three quarters of the 17 th century; at least until he was 60 he was a key figure in the prevailing religious and political strife. Born in Buckinghamshire and graduating from Brazenose, Oxford, Johnson was a scholarly defendant of the Anglican settlement and prayer book established during the reign of Elizabeth I. Appointed curate of Gorton in 1628 he became its minister shortly after, in which post he befriended Chetham, who owned the neighbouring Clayton Hall and its extensive lands and was already a powerful civic figure. Perhaps as a result of this friendship Johnson became a fellow of Manchester Collegiate Church in 1632.

The lives of Johnson and Chetham were thereafter intertwined. Chetham was conscientious in cultivating friends from all parties but Johnson saw it as his calling to maintain the collegiate church as a bulwark against growing puritanism around Manchester and the entrenched catholicism in the rest of Lancashire. This was no easy task. In the year of Johnson’s appointment another fellow of the college, Daniel Baker, drowned under Salford Bridge. Either he was ‘overcharged with drinke’ or, as was alleged with several other protestant clergy, he was murdered. This was a time when men, even scholarly clerics, went about their business armed with daggers. The affairs of the collegiate church were in disarray, partly as a result of the absentee wardenship of John Dee and then Richard Murray. When Johnson took up his fellowship he was shocked: he wrote to Chetham that Richard Murray had fallen or been thrust into ‘recklessness of most unclean living’ and subsequently he became embroiled in a confused and distinctly ungodly tale of greed, accusation and counter- accusation. Murray was eventually imprisoned for embezzlement and bastardy. His supporter Peter Shaw claimed that some were ‘seeking to disgrace him by secret calumnies and slanderous letters.’ Shaw accused Johnson in his turn of embezzlement, failing to wear the surplice, administering the sacrament to private seats, omitting parts of divine service, and neglecting Gorton chapel. It is ironic that some of these sins, seen as signs of non-conformity, were imputed to Johnson, who was entirely conformist. Humphrey Chetham, now Receiver of the College Revenues, was well aware of the situation, and Johnson was effusive and frank in his thanks to Chetham for his ‘warninge concerning our subtile and wily enemye’ and opined that Murray would ‘lye in prison till hee stinks before he will pay.’ This was hardly the language of devout Anglican scholarship. He went on to make a not altogether convincing defence against the allegations to Archbishop Laud, including the statement that he had constantly worn the surplice ‘unlesse it were some one day or another in the washinge … or through the negligence of the clerk.’ Was there no surplus surplice?

Metal cut showing an Anglican Priest in his surplice, as he might have appeared circa 1600.

Despite all the skullduggery, Johnson emerged as the man to negotiate with Archbishop Laud and the privy council for a new charter and reform of the Collegiate Church. Encouraged and financed by Chetham, and thanking him for his support, Johnson set off for London to plead his case and secure agreement about the future management of the church. This was an onerous task, as Johnson made clear in letters to his friend. By August 1635 nothing was settled, and he wrote: ‘I must stay till ye Kinge cometh agayne to London before I can have his hand or knowe who shall be Warden. Charter must pass through three seales and be foure tymes transcribed in parchment or in vellum … Letters of sequestration of ye tythes are in forgeinge. I use my skill. God bless you.’

Even at this time Johnson was aware ofthe dangers of such free expression of opinion. He urged Chetham, clearly to no avail, to ‘do as much for this letter as I did for yours; sacrifice it to Vulcane.’ The closeness of the two men is further illustrated in a letter from Johnson to Chetham about the christening, at which he was sponsor, of the latter’s nephew and namesake. Eventually Johnson was vindicated, the charter was sealed and a new warden appointed, Richard Heyrick. Although at that time showing non- conformist tendencies and later joining the presbyterians as a covenanter, Heyrick was a man Chetham could do business with. Building work was undertaken in the collegiate church, partly financed by Chetham. Posts, wages and finance were settled. Johnson retained his fellowship and served alongside his ‘wily enemye’ Peter Shaw. Johnson had demonstrated his skills as a negotiator and ambassador, but felt he owed a great debt to his deare friende. His letters show the staunch support he in his turn provided to Chetham in times of trouble. The first of these was when Chetham was accused of ‘borrowing’ a coat of arms from another family and not following proper heraldic practice. In a long letter in June 1635, Johnson wrote ‘I might justly be condemned of a pragmatical humour, or as a busy body in other men’s matters if I had not been intreated to yeild my advise, Sir, I perceive that some malicious knaves have endeavoured to disgrace you about your Coate of Armes.’ He went on to warn Chetham to be careful of certain alliances as some of the Lancashire (no doubt catholic) gentry were displeased with his presumption. In the end, Chetham’s loyal work as Sheriff, and some greasing of palms, saved his reputation and secured the arms we now see in the library.

Further moral support was given when Chetham was involved in disputes and accused of fraudulence over leases of the church lands, and later when he upset tenants with his attempts to boost income from his estates. Chetham survived these setbacks and when he reluctantly accepted the post of Sheriff of Lancashire (which made him a glorified tax collector for the King) he appointed Johnson, still in London, as his chaplain. So effective in performance of his onerous duties was Chetham during the early reign of Charles I that years later, in November 1648, Parliament nominated him again as ‘Sheriffe of the Countie of Lancaster’. This time there followed a bitter struggle to evade the honour, in which he was once again energetically supported by his friend Johnson, who joined others in the effort to get the nomination annulled. During this campaign Johnson wrote to Chetham: ‘Sr, we will doe what we can, be of Good cheere, I think you may with conscience, beinge so ould (he was 68) and weake and broken with cares, pleade want of abilitie in memory and understanding and thus be released from the burden.’ Johnson opined that some rich and great man may be found. He had been talking to his contacts in Parliament and suggested that if the plan did not work Chetham should petition Parliament to appoint two under-sheriffs to do most of the work. Johnson was well aware that any resistance to Parliament was dangerous. Referring to another letter, he wrote: ‘I did not for a tyme dare to write an answer for some letters use to be opened, I think you understand mee.’ He was full of a sense of doom. ‘The Lord have mercy on us … men’s mouths are sewed up … if the Soldiery take all ye power and new modell ye kingdom, it is a question how little will be left to you to doe, and it may be the lesse the better’. The crisis was all over for Chetham by April 1649. The King was dead, the Commonwealth established, and John Hartley of Strangeways was appointed sheriff.

Johnson had every reason to be cautious. In 1646 parliamentary supremacy in Manchester had led to the suppression of the Church of England and the establishment of presbyterianism in a ‘godly reformation.’ Johnson’s Anglicanism and suspected royalism led him to lose his fellowship in the chaotic early days of the Commonwealth, when the college was dissolved and the warden and fellows dismissed. It was said, clearly by a fellow royalist, ‘Ye greatest sufferer was Mr Richard Johnson, fellow, a pious, learned and sober man. He was carried to Lancaster or Chester Jail, and stoned in the streets here and they carryed him to prison for his loyalty and because he was utterly against ye Republicans, and Cromwel’s tyrannous usurpation. The fellows who seized him would not permit him to put on his boots, but he was forced to twist whisps of straw or hay round his legs to defend him from the dirt; and in this posture they mounted him upon a poor, ragged little beast’. Despite this ignominy Johnson returned to London on his release, first as preacher then as Master of the Temple Church, in which role he became involved in the acquisition of scholarly and religious books for its library, the Inns of Court being at that time both a training ground for lawyers and a finishing school for the gentry. He may have become acquainted with Robert Littlebury, a renowned buyer and seller of books and a man of ‘composed and serious countenance’ who later played animportant part in supplying books for Chetham’s library. Johnson continued his frank correspondence with his friend, sending dramatic accounts of riots and disturbance in the capital against the new regime and saying that he proposed to stay at the Temple until ‘ye Lord be pleased to putt ye Kingdome in some more peaceable and stable condicion.’

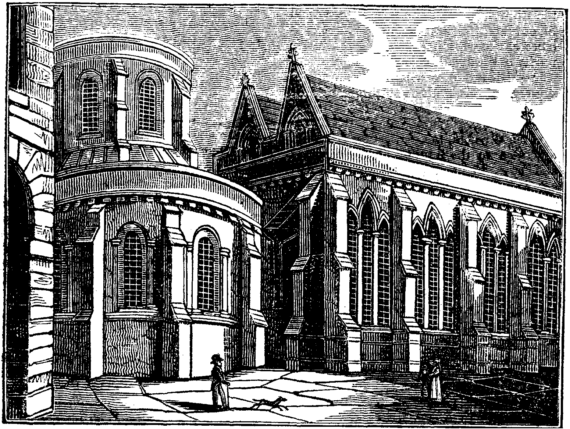

A woodcut image of the Temple Church.

When Chetham died in September 1653 Richard Johnson was of course remembered in his will. He featured in the list of feoffees as ‘Gentleman Richard Johnson Clerke late one of the Fellows of the College in Manchester’ and was nominated as one of a trio entrusted with the acquisition of books for the church libraries. Johnson and Chetham’s friendship, their affiliation to Gorton and Johnson’s skill as a preacher no doubt influenced the choice of Gorton as one of the parishes where a library would be established. Chetham also requested that Johnson should preach his funeral sermon and further decreed: ‘I give unto my lovinge friend Mr Richard Johnson preacher att the Temple London three score pounds’. At the famously lavish funeral Johnson was furnished with a mourning suit for which £7 was provided from the expenses. Even before the scholarly library was established Johnson, together with Richard Hollinworth and John Tilsley, began the business of acquiring ‘godly books (in English) for the edification of the common people’ for the parish libraries. After the Restoration in 1660 Johnson’s fellowship of the collegiate church was restored. He seems to have acted with prudence and discretion working alongside colleagues with different religious and political allegiances. In 1660 one of his renowned sermons began: ‘The name of Liberty is very precious. The thing which men call Liberty is desired by all, abused by many, understood by very few.’ As a feoffee of the Chetham foundation he now took a leading role. Their minutes of 27 May 1661 note: ‘Mr Johnson and Mr Edward Chetham at the desyre of the other feoffees doe intend to meet at London about this day six weeks to endeavour the Incorporating of the Hospital and Librarie from his Majestie.’ The instructions for this charter include the provision: ‘Mr Johnson to be named the present Librarie Keeper in the foundation for his life (if hee accept of it) with such yearly stipend and salaries as shall be thought fit by the feoffees.’ The royal charter was finally granted four years later on 10 th November 1665.

The earliest acquisitions for the library were, appropriately, of a theological nature, geared towards the concerns of local preaching clergy and scholars. Invoices covering the period of Johnson’s tenure provide rich evidence not only of the books acquired but of other expenses in getting them delivered from London. For example, on 2 August 1655 we learn that the cost of ‘carriage of it (the consignment) with ye chains, Rods, ye chains for patternes’ was £0.2.5d.’ After the first theological purchases, the librarians began to collect classical works, and then branched out into natural history, travel, law, medicine, history and science. During Johnson’s period of office at least two English works of distinction were acquired:

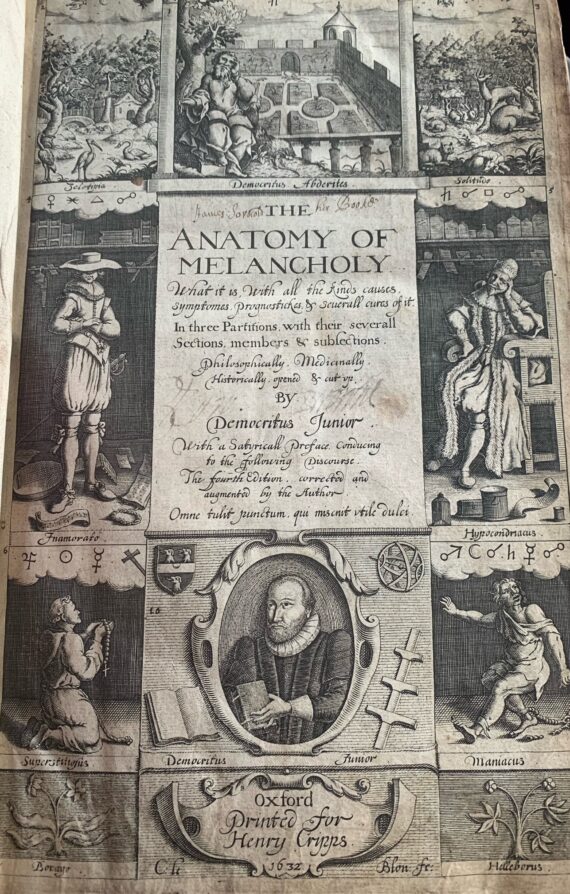

The Anatomy of Melancholy by Robert Burton, 1658, is a vast medical textbook, but also a work of literature, science and philosophy, both serious and satirical in tone. In the preface Burton explains ‘I write of melancholy by being busy to avoid melancholy.’ It cost ten shillings.

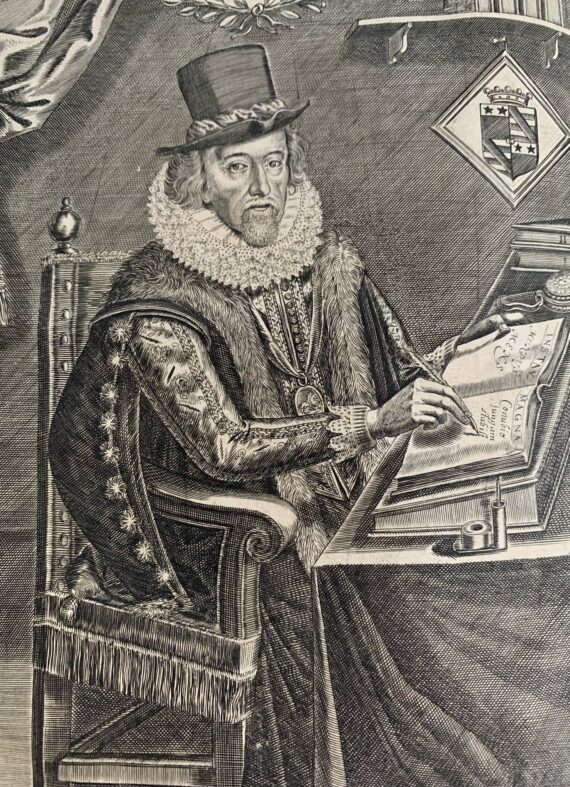

Francis Bacon shown in The Advancement of Learning of 1605. He broke new ground by arguing that the only knowledge of importance was that which could be discovered by observation- ’empirical’ knowledge rooted in the natural world. The book cost 8 shillings.

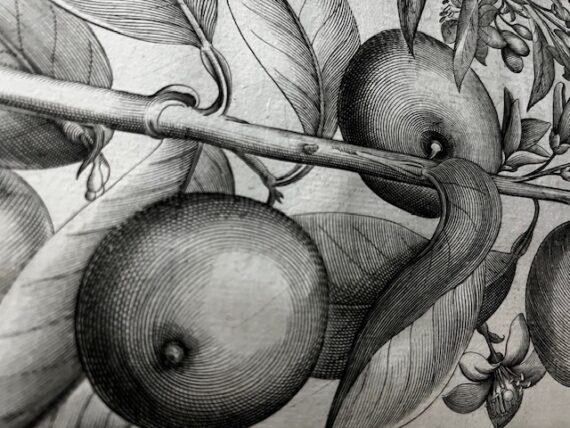

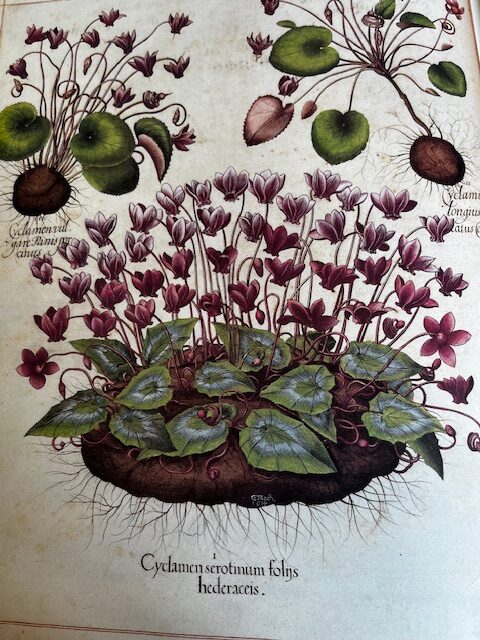

The most valuable book acquired during this period was Besler’s Hortus Eystettensis (The Bishop’s Garden) of 1613.

A detail from this botanical masterpiece, which measures 55 x 44cm and takes two people to lift. It is printed from elaborately prepared copper engravings and has 367 plates illustrating more than 1000 species

A very few copies of the Hortus Eystettensis were printed on special paper and hand coloured by teams of illuminators

It is to be hoped that Johnson took some pleasure in the acquisition of such treasures in the name of his old friend. The library keeper’s footprint grows fainter towards the end of his life. He remained nominally in post but took up a living as rector of St Paul’s church, Broadwell, Gloucestershire, whose clergy house was at Adelstrop, while Robert Browne and then Edward Lees acted as deputies at Chetham’s Library. Johnson continued to preach thoughtful and scholarly sermons, and died in 1675, perhaps having finally enjoyed some respite from religious strife away from the turbulence of Manchester.

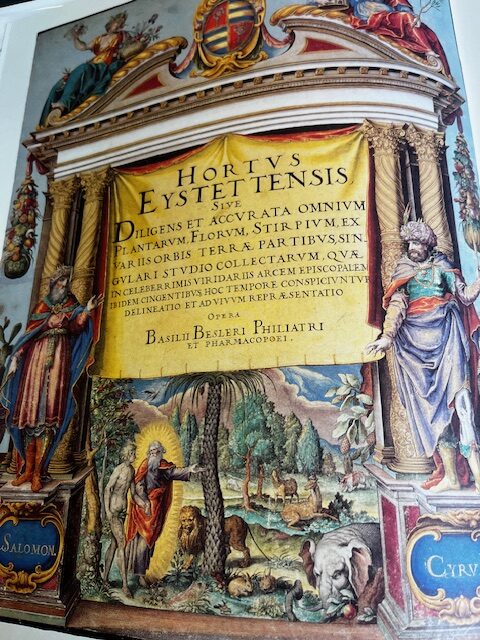

Title page of one of the coloured editions. Both the above reproduced in Hortus Eystettensis : The Bishop’s Garden and Besler’s Magnificent Book> Nicolas Barker, 1994

Title page of one of the coloured editions. Both the above reproduced in ‘Hortus Eystettensis : The Bishop’s Garden and Besler’s Magnificent Book.’ Nicolas Barker 1994

Sources

Cunliffe Shaw, R. ‘A Lancashire Clerical Family of the 16th and 17th centuries.’ Historic Society of Lancashire and Chesire, 1963

Groves, Gill. ‘Reverend Daniel Baker – Murder Victim?’ Ashton and Sale History Society Journal 32 2017

Guscott, S. J. Humphrey Chetham 1580-1653. Chetham Society 2003

Purdy, J G. Parish Libraries and their Readers in Early Modern England. PhD thesis, MMU 2021

Raines, Robert et al. The Life of Humphrey Chetham. Chetham Society, 1903

Raines, Robert. The Fellows of the Collegiate Church of Manchester Chetham society, 1891 ; Digitized, Aug 8, 2005.

Snape, Anne. ’17th Century Book Purchasing in Chetham’s Library.’ Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, University of Manchester 1985

Yeo, Matthew. The Acquisition of Books by Chetham’s Library 1655-1700. Leiden, Boston 2011

By Kath Rigby

3 Comments

Denise Carter

An utterly fascinating and enlightening blog. Terrific.

ferguswilde

Thanks, Denise – we’ll be asking Kath to write more, and very glad to hear you enjoyed this one!

Sue Richardson

Fascinating, and it really gives a good picture of how hard it was to collect books in those days without being prosecuted. Nice that someone who contributed so much to the library is finally being appreciated.