- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

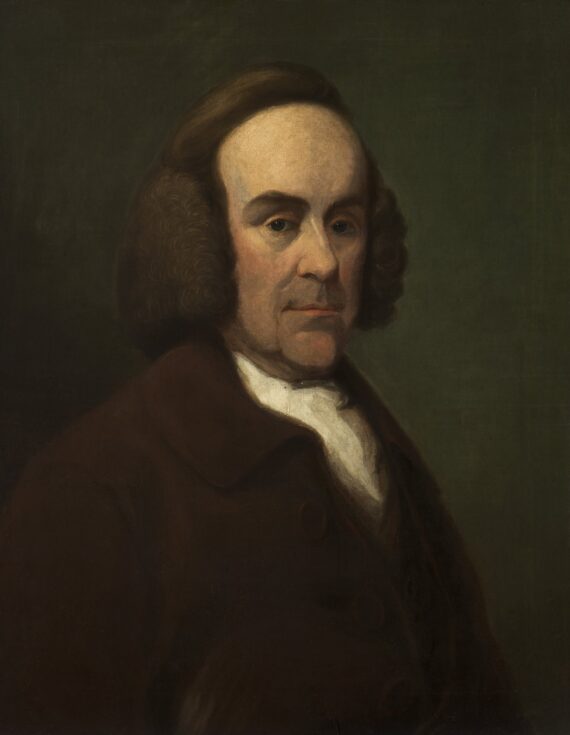

Robert Thyer: Sophistication and Simplicity

Thyer was Chetham’s 9th librarian, its first layman and up to that point its longest serving incumbent; he held the post for over 30 years from 1732 to 1763. He was a Manchester man, the son of a silk weaver, educated at Manchester Grammar School and Brazenose College, Oxford. Thyer’s appointment is recorded in the Feoffees’ minutes but we do not know how he achieved this position at the early age of 23. Then, as now, contacts were important and Thyer was a great cultivator of friends, many of whom were influential.

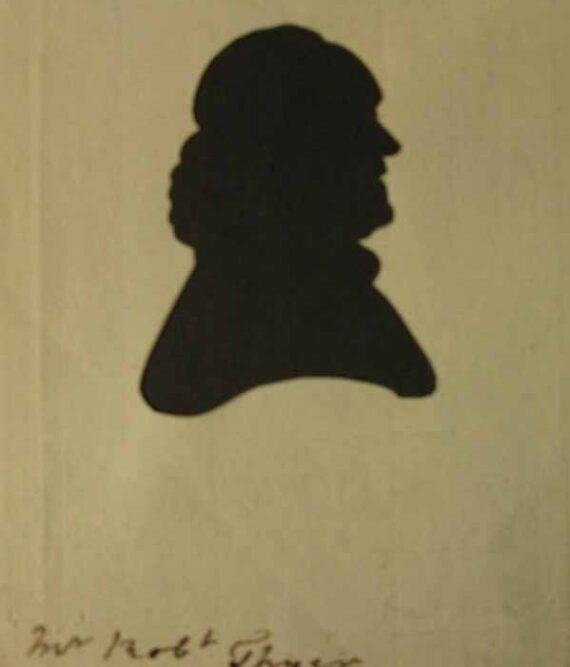

Robert Thyer Paper Portrait Silhouette, by Dorothy Byrom. Manchester Art Gallery.

In affectionate letters to his relations later in life, Thyer was at pains to let it be known that he was meeting with the country gentry on intimate terms. He may have been acquainted with George Booth, the 2nd Earl of Warrington at Dunham Massey who sent troops in support of the Jacobites, a cause espoused by Thyer, in 1745. More significantly, Thyer had a family relationship with Booth’s neighbour, Samuel Egerton, grandson of the 2nd Earl of Bridgewater: Thyer’s wife had previously been married to John Leigh, Egerton’s cousin. Egerton succeeded his childless brother as owner of Tatton in 1738 and when his wealthy uncle, Samuel Hill, died, he inherited significant additional estates as well as a fine collection of art and books, many acquired in Italy. Egerton had intriguing links, familial, political, artistic and social, all over England. He became an MP and a leading, if eccentric, figure in Cheshire society. While renovating his ancestral home at Tatton, one of his most important projects was the building of a new library for his uncle’s outstanding collection of books.

The combination of a family connection, Egerton’s Tory sympathies, and his rare and valuable book collection drew him into friendship with Thyer, who spent many long periods at Tatton after his retirement. A letter from Egerton’s daughter to Thyer pleads for his presence and indicates that he was always a welcome and honoured guest. Egerton was not only good company, but a source of funds for the comparatively poor librarian. Thyer eventually benefited from Egerton’s will, writing to his stepdaughter in 1780 that he was overjoyed that his debts had been forgiven and that he was to receive £200 a year and ‘the 40 pounds a year I have enjoyed from him for some time past’. He adds, ‘This is enough for a Philosopher’ and he assures his stepdaughter that he will not let his riches affect him. He was only to enjoy this modest wealth for a year before he died.

Thyer’s earlier intimate circle was more literary. He was a close friend of John Byrom, the Manchester poet and inventor of a system of shorthand, known later for the lyrics of the stirring hymn, ‘Christians Awake!’ The French scholar, Henri Talon, in his ‘Selections from the Journals and Papers of John Byrom’ of 1950, paints a vivid picture of the friendship of these two literati. They walked and dined together; Byrom would keep an eye on the library when Thyer needed some time off for exercise or to watch a foot race; they sent effusive greetings to each other’s wives. Byrom’s wife created an affectionate silhouette of Thyer, now in the Manchester Art Gallery.

Thyer would sometimes emulate Byrom’s light-hearted verse. When his cobbler provided shoes that were too big, Thyer sent them back with an admonitory note:

How couldest thou get in thy pate.

A foot like mine, so small, so neat,

So pretty, if the beaus say true,

Could ever fill so huge a shoe?

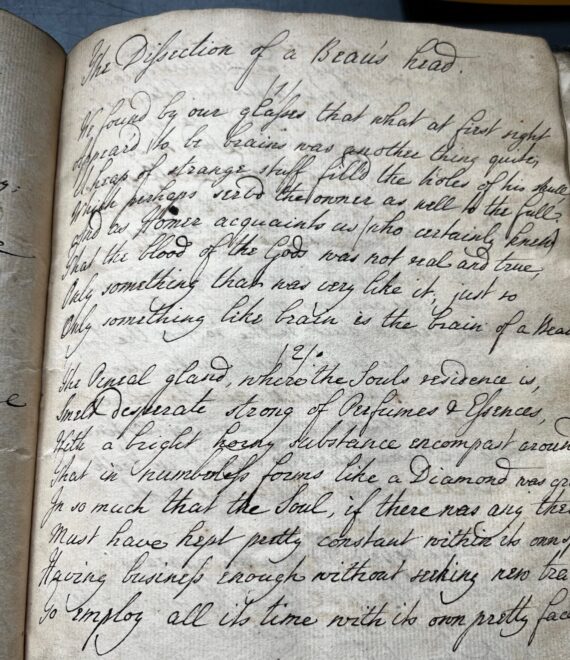

The reference to that much-satirised mid-18th century phenomenon, the beau, might have been influenced by Byrom’s poem ‘The Dissection of a Beau’s Head’, a grisly description of what might be found on opening up a fashionable dandy, which begins

We found by our glasses that what at first sight

Appeared to be brains, was another thing quite,

continues for several pages to examine intimate body parts which are not what they seem and ends with the promise ‘we’ll reserve the Coquet for another occasion’. This and other poems were painstakingly copied out by Thyer in a manuscript collection held in the library, indicating that he fully supported Byrom’s scorn for high fashion.

‘The Dissection of a Beau’s Head’ by John Byrom, in Robert Thyer’s hand. In Chetham’s Library.

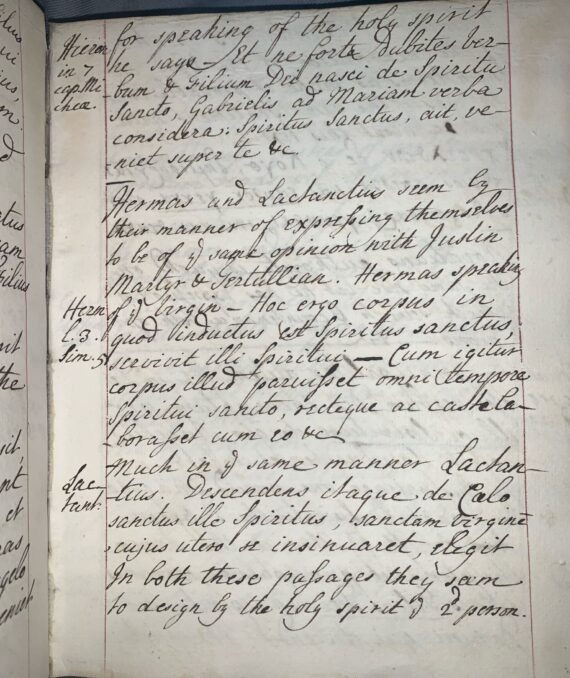

All this friendly simplicity is in contrast to the sophisticated scholarship for which Thyer was renowned. His meticulous manuscript commonplace book of 1743 consists of a series of essays, mostly in Latin but partly in Greek, with titles such as ‘On the Thief upon the Crop and the Case of Deathbed Repentances’ and ‘On the Descent of the Holy Spirit in the form of a Dove’.

A page from Robert Thyer’s Commonplace Book, 1743, in Chetham’s library.

In further scholarly endeavour, he supplied notes for a new edition of Paradise Lost compiled by Thomas Newton, who described Thyer as ‘a man of great learning and as great humanity.’ He went on to edit ‘The Genuine Remains in Verse and Prose of Samuel Butler,’ much praised, albeit controversially, by Dr Johnson. A new edition of ‘The Remains’ came out in 1827 long after Thyer’s death, which included a copy of the Romney portrait (below). John Hill Burton 40 years later in his ‘Bookhunter’, thinking Thyler had in some way been responsible for this vainglorious inclusion, spoke waspishly of ‘drudging Thyer’s respectable and stupid face.’ It is not clear how Burton formed this opinion, but all the evidence indicates that Thyer, although indeed respectable and perhaps a little ‘drudging’ in terms of his conscientious and scholarly approach to his various projects, was far from stupid.

Manchester Grammar School remained close to Thyer’s heart and he contributed for many years to their rather solemn and admonitory Christmas celebrations. In the early 1760s, he wrote a verse prologue and two speeches. After his retirement, he produced three lengthy essays for the school. The first, in 1773, was a denunciation of avarice, urging ‘the proper use, not the hoarding’ of riches. It ends with a striking simile. Riches, ‘judiciously scattered’ are like water, ‘which, purified by continual motion, and skilfully conveyed in different rills to ye parts which want it, diffuses plenty and beauty wherever it flows; but, if suffered to stagnate in one place becomes putrid, loathsome and prejudicial to that very land which it was designed to enrich.’

The second essay, written in 1779, is a diatribe against the use of malicious satire in literature. The end of all wit, he advises, should be humane and benevolent, and should never ‘torture a man for being odd and singular’. The essay ends: ‘He that is malevolent enough to laugh today at his neighbour’s expense, should consider that tomorrow he may be ridiculed at his own; and he will then too late find by experience that the Sensibilities of Men are not to be dallied with and may feelingly say with the Frogs in the Fable – what is sport to you my Lads is Death to us.’

Finally, in 1780, his advice to pupils was encapsulated in Simplex Munditiis, in which he argued that ‘there is a certain dignity in simplicity which will always please’ and maintained that ‘the simplicity of Nature is the ground and foundation of every real excellence.’ In literature, ‘words are the dress of Thought as Cloaths are of the Body’ and in personal appearance ‘charms borrowed from Art are incapable of attracting…the Admiration and Esteem of the other sex.’ Thyer’s essays seem to illustrate his character perfectly – a man of gentle and kindly humour, humane, fond of fun but somewhat straitlaced, an advocate of a simple and thoughtful life, and an enemy of the fashionable and false – ‘the coxcomb, foppishness, the Friseur and the Rouge Box.’

Librarians at Chetham’s traditionally trod carefully in matters of politics and religion. Thyer however made no secret of his Tory and Jacobite sympathies. When Charles Stuart arrived in Manchester in November 1745 on a recruiting mission, Hanoverian troops were sent to root out Jacobite sympathisers. A family anecdote relates that Thyer took refuge in Heaton Hall. When the soldiers searched his house in Long Millgate for treasonable papers, his wife showed her spirit by suggesting they should look under the winter’s supply of coal for there they might find her husband as well as the papers they sought. Throughout this period Thyer supported his friend Byrom in local controversies with the Whigs. Particularly bitter was the friends’ condemnation of Josiah Owen, a Presbyterian minister from Rochdale and a voluble and virulent opponent of the Stuart cause, who in 1746 celebrated its eventual defeat with a Sermon entitled, All is well; or the Defeat of the late Rebellion … an exalted and illustrious Blessing. John Byrom retaliated haughtily, referring in An Epistle to a Friend (possibly Thyer) to ‘the low-bred O——ns of the age’, and publishing a scurrilous ballad on The Zealot of Rochdale, under the title Sir Lowbred O .. N, or the Hottentot Knight. Although he joined in the fray at the time, this brand of satire would not have been approved by the older Thyer.

Thyer married Silence, widow of the well-connected John Leigh, in 1741 when he was 32. She died 12 years later and all that remains of her is her list of the birth dates of her children written in an uncultivated hand and her complicated will constructed in 1751. The couple had no surviving children, but his stepdaughter, Elizabeth Leigh, filled the role of housekeeper when Silence died. After he retired, and when she had become Mrs George Killer, the wife of a hatmaker, he gave the couple use of his house and wrote warm and loving letters to his dear Bessie, signing himself ‘your affectionate Pappa”. He considered her children, Elizabeth, Robert and John, to be his close family. Letters to the younger Elizabeth, whom he called Bet, are full of elaborate compliments and encouragement. He makes frequent reference to her brother Jack, enquiring after his health and sending love. The other brother, Robert, was taken by Thyer to Liverpool when he was 11 to recover his health and enjoy the sea-bathing. Staying in fashionable Wolstenholme Square, the Manchester Grammar School student ‘[wrote] his Latin every day’ but found time to buy a gift for his elder sister – an expensive sixpenny coconut which disappointingly went bad. Both Robert and John became respected doctors in Manchester and Stockport. Robert was later known for treating the poor without charging for his services.

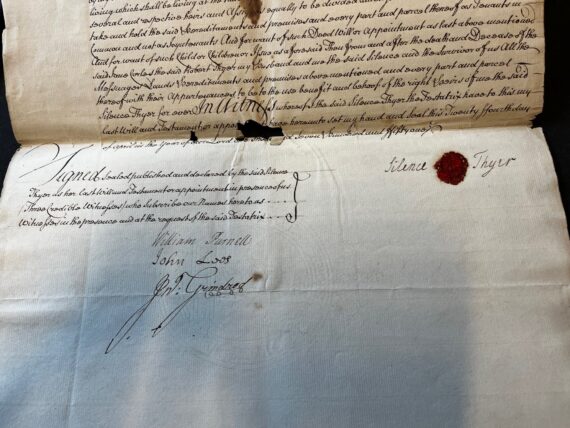

Last page of Silence Thyer’s will. In Bellot papers, held by John Rylands University Library.

Although single for many years Thyer was certainly not lonely or reclusive. In his letters to Bessie he reports many tea parties, balls and dinners with a wide range of friends, alludes frequently to the delicacies of the table, and in Liverpool one evening he ‘had the pleasure of a lady’s company to sup and drink a glass of wine with me.’ Earlier, two grammar school boys, John and Richard Arden, lived with him for a period and received tuition. He maintained his interest in horse racing in later life and rather sportingly travelled by boat in 1778 from Altrincham to Manchester when returning home from Tatton. He did, however, regret the passing of time and his inability to grow young again, as he reported to Bessie, despite ‘taking the bitters’ as she had recommended. There are many references to his rheumatism and walking difficulties, his state of health being ‘better or worse according to the weather.’ He reported more cheerfully to Bessie from Liverpool that ‘my bathing agrees extremely well with me and from the most shocking extremity I am, thank God, restored to a more probable way of mending.’ He was always concerned too about the health of others, and especially his step-grandchildren. In a last letter to Bet he wrote ‘I give you no advice about your conduct, which I am sure will be right, but let me advise you to take care of your health.’ Sadly, Bet did in fact die six years later at the age of 24.

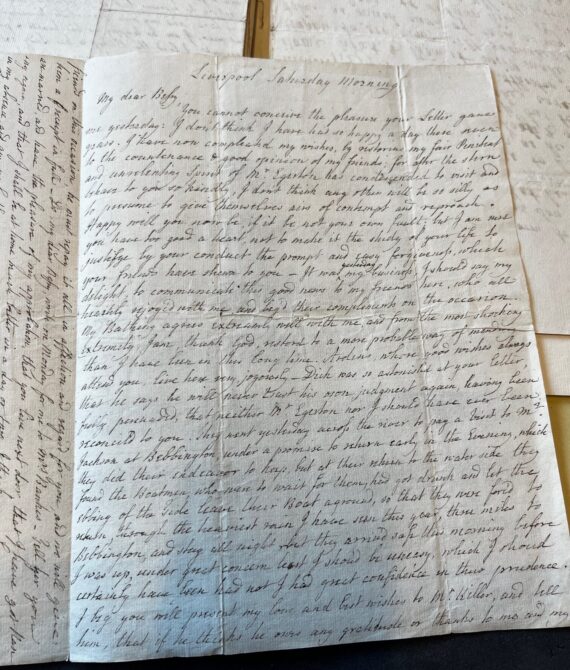

One of Thyer’s letters to his stepdaughter in which he shows how important to him was the esteem of his friend Samuel Egerton, and tells a comical story about a drunken boatman. In Bellot Papers, JRUL

As for Thyer’s work as a librarian, he was always active, compiling the first catalogues, travelling either to buy books in London or to supervise the estates of the foundation in Lancashire and Yorkshire. His successor, Robert Kenyon, ‘enriched the library with a large collection of books pertaining to Natural History, engravings etc’ according to the next librarian, John Radcliffe who took over in 1787. But Radcliffe’s most lavish praise was reserved for Thyer. He explained that two catalogues were compiled during Thyer’s tenure ‘by one who can never be mentioned without praise, to whom Milton is indebted for much light thrown upon his immortal poems…and for almost all of (the library’s) elegant and choice selection of books.’ The two catalogues compiled by Thyer were said to have been created according to the plan of Middleton who advocated the use of alphabetical order together with ‘the indication of the class and place of a book to use as an index so that we may impart to learned men…the publication of a distinguished catalogue (which) confers the greatest benefit to the world of literature, and the greatest assistance in promoting and perfecting literary studies.’

Thyer’s diligence as librarian was certified by the trustees on his retirement and in the Latin preface to the library catalogue of 1791. He continued to travel, write, and socialise, sometimes at Tatton and sometimes at his house in Long Millgate, until he died on 27 October 1781 aged 72, leaving Chetham’s library a richer and more orderly place of learning. He was buried with some ceremony with his ancestors at Manchester Collegiate Church.

By Kath Rigby

2 Comments

Christine Harrison

Thank you for a very interesting article – it sounds as if Robert Thyer was a very conscientious and diligent librarian – ideal qualities for a position like this!

Just as a very small footnote, his Wikipedia entry mentions that Silence’s first husband, John Leigh, was the great-great-grandfather of Lydia Becker, one of the most famous Suffragettes of the day and herself a native Mancunian. Incidentally, I was very intrigued by the name Silence – I imagine that silence was what was expected of her, in common with a lot of the female sex at the time!

Bruce Thyer

A very interesting essay. My family left Manchester for the USA in the 1870s, but alas, I have not been able to track down a familial connection with Robert Thyer. Bruce Thyer is my name and I have ancestors buried in Altrianham (sic) and St, Mary’s Astbury, in Cheshire). I have visited Chetham’s Library and have seen his portrait there. Correspondents interested in Robert Thyer are welcome to contact me. Bthyer@fsu.edu