- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

The Accedence of Armorie: Sixteenth-Century Paint by Numbers

The top shelf of the last press in Chetham’s Library, press Z, is home to a copy of Gerard Legh’s Accedence of Armorie (shelfmark Z.1.64). Having accessed the book in this remote location, the enterprising librarian is rewarded with a beautiful book: Legh’s work illustrates the basics of blazon, the symbols and colours depicted on coats of arms. The Library’s copy of the Accedence (a word defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as meaning ‘fundamentals’ or ‘first principles’) has been carefully coloured in by one of its early readers, whose efforts have turned the title page into a vibrant work of art. It is possible that the artist was Thomas Tyndale, whose signature can be seen on folio 96r. In addition to the woodcuts and hand-colouring, the book also includes a foldout illustration of a particularly elaborate coat of arms, flanked by the mythical figures Hercules and Atlas.

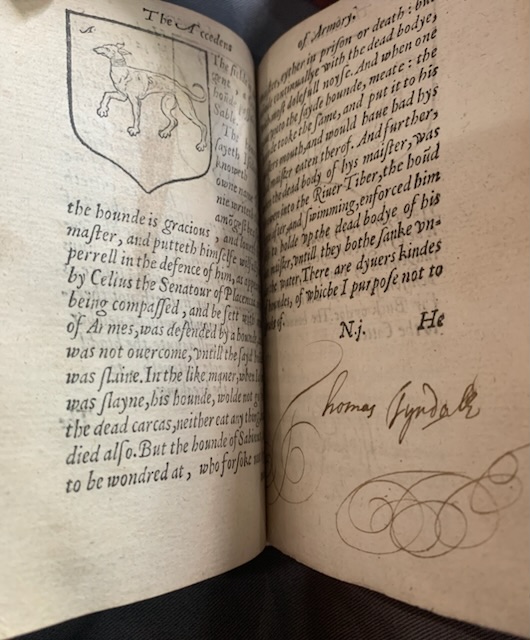

Signature of Thomas Tyndale, folio 96r.

The book is a good example of the interaction between printed books and handwritten additions by readers. Manuscript culture did not simply disappear with the advent of printing in Europe in the fifteenth century: rather, manuscript and print coexisted for many years, and many early printed books relied on professionals or readers to ‘finish’ the book, for example by filling in initial letters or colouring in images.

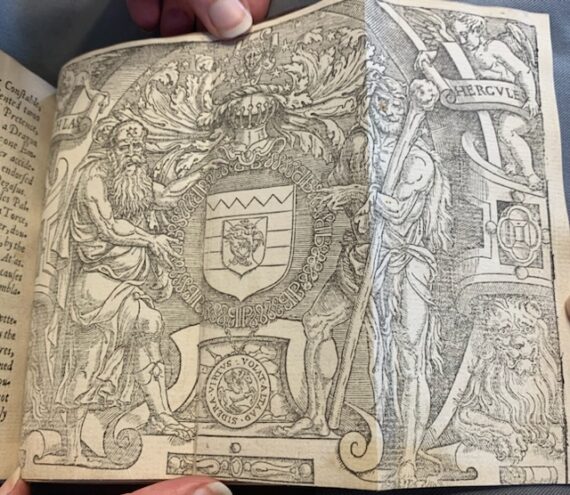

Foldout illustration of a shield flanked by Hercules and Atlas.

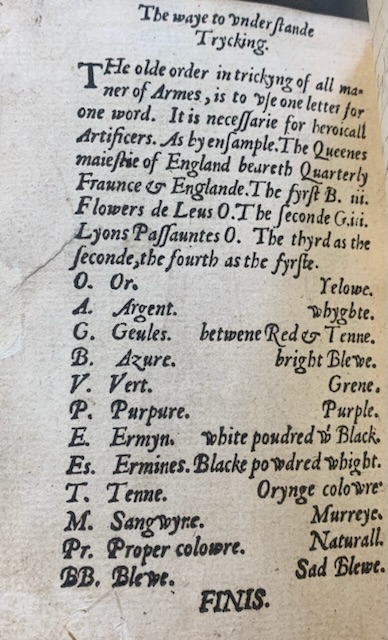

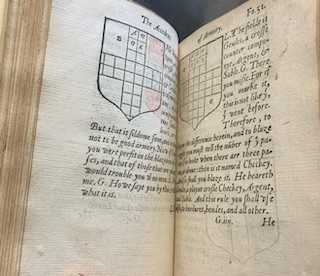

Legh’s work similarly invites its readers’ cooperation: for example, the book is printed in black and white, but because colour is an important part of a coat of arms, detailed instructions for readers are included, specifying which part of any coat of arms should be depicted in which colour. To achieve this, the book includes small letters in every section of the images, each of which stands for a colour. The letters and corresponding colours are all listed carefully in a table at the back of the book, rather like in a modern ‘paint by numbers’ set.

Table of colours.

The table uses the Anglo-Norman French widely spoken at court in the Middle Ages, when blazon was originally developed. For instance, ‘O’ stands for ‘or’ – the term still used for ‘gold’ in modern French. Similarly, ‘V’ is for ‘vert’ (French for ‘green’) and ‘A’ for ‘argent’, ‘silver’. The reader of the Chetham’s Library copy has carefully followed these instructions, colouring in every coat of arms up until folio 50r.

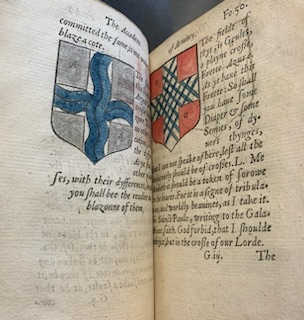

Last page with hand-colouring.

At this point, the reader seems to have lost interest or was unable to complete the project for an unknown reason, and the subsequent coats of arms all remain uncoloured. Nevertheless, the Accedence of Armorie shows how closely some readers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries engaged with their books as they carefully completed the work begun by author and printer to create a coloured copy of the work.

First page with uncoloured coats of arms.

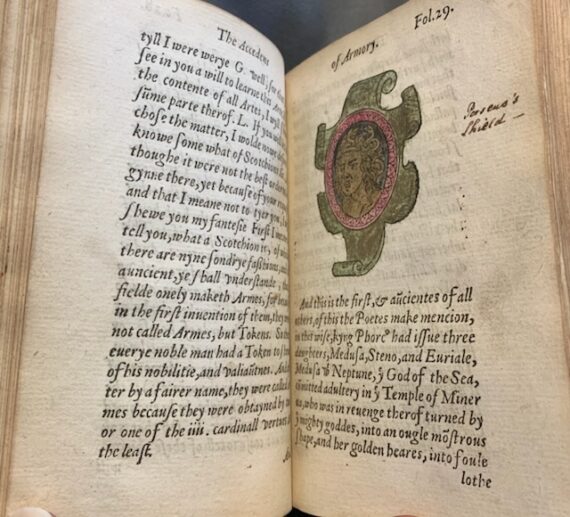

While metallic colours like gold and silver have turned very dark due to oxidization, most other shades retain their original vibrancy. The first shield described in detail, for instance, the mythical shield of Perseus, depicting the head of Medusa, includes a bright pink border and a deep blue background. Other images show shields with animals like goats and elephants, all carefully hand-coloured by the reader.

The shield of Perseus with the head of Medusa, fol. 29r.

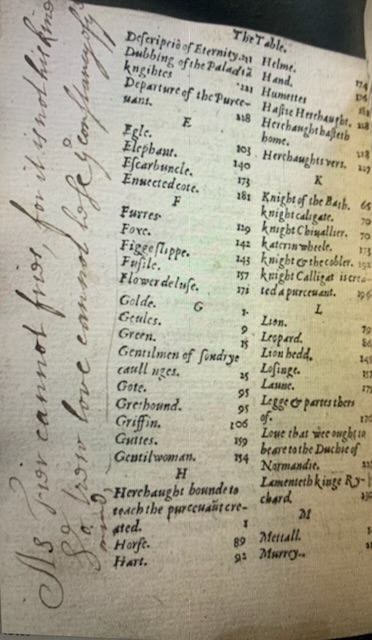

Although the Chetham’s Library copy of the Accedence of Armorie demonstrates such intense focus on the part of one reader, it also bears marks entirely unrelated to the text of the book. On a page containing a kind of index towards the end of the text, a sixteenth- or seventeenth-century reader has written:

‘As Fier [‘fire’] cannot fries [‘freeze’], for it is not his kind

So trew [‘true’] love cannot lose the constancy of the mind’

Manuscript verse at the back of the book.

Perhaps this was the work of a different owner, or perhaps the diligent colourist became distracted by a love affair and turned to recording romantic verses rather than completing his work on the Accedence of Armorie. Either way, this single book demonstrates two distinct ways in which readers in the past engaged with their books: while one reacted to the text, having closely observed the author’s instructions and the purpose of the book, the other used the book more or less as we would use a notepad, in a way that is not tailored to the text, but rather simply makes use of empty space on a random page. The result is a unique and beautiful copy of Legh’s work, bringing together printed texts and two very different kinds of readers’ marks.

By Ellen Werner.