- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

The Bards of Cottonopolis: Poetry and the Labouring Class

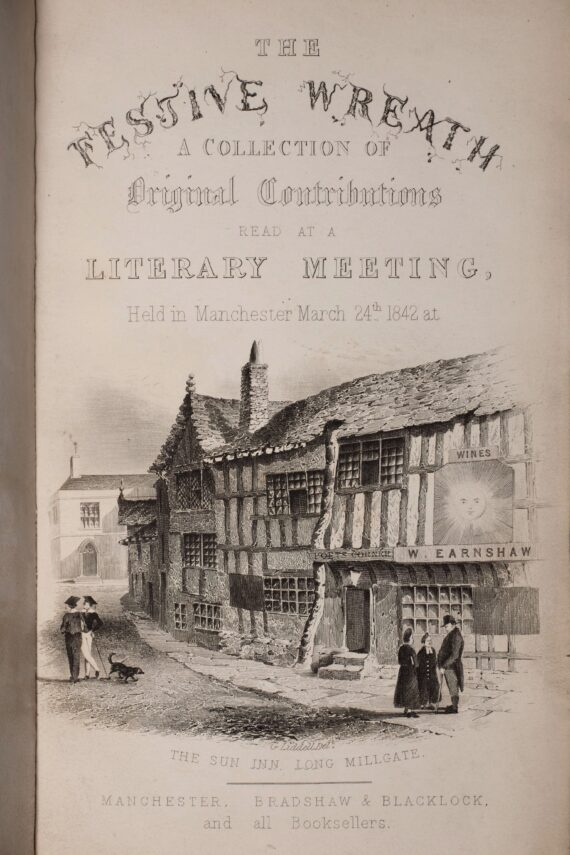

Grey and bustling, Manchester emerged during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as the first industrial city, churning out cotton through its steam mills and the toil of the labouring class to the great profit of the wealthy. Consequently, although it was cotton-rich, the city was seen to be culturally poor, since its inhabitants were more interested in generating capital than producing art. At the Sun Inn on Long Millgate, however, one could find Poet’s Corner and the Sun Inn Group, whose poetry challenged this perception of Manchester.

The Sun Inn Group, composed mainly of labouring-class poets, gathered in this public house to share ideas and their writings. One of its members, John Critchley Prince, was a reed maker, becoming an apprentice to his father at the age of nine to help provide for his family; other members were barbers (Richard Wright Prochter) and weavers (Samuel Bamford), who worked alongside their writing to support themselves and their families. The act of creativity, and especially the writing of poetry, can be understood as a radical act in the midst of the conditions of the poor, challenging perceptions about the Mancunian labouring-class mind. Labouring class professions were monotonous, requiring long hours for meagre wages, and factories were equalled in their cramped, poor conditions by the inhospitable homes to which factory workers returned. As a result of this inequality, Manchester was known for being politically-influential, leading the Chartist movement, which was concerned with the rights of the working class, working for better conditions and reforming attitudes towards the working class. The growing class consciousness and a desire for better amongst the labouring class that this movement reflected is also reflected in the poetry of the Sun Inn Group.

Figure 1: Long Millgate and the Sun Inn, depicted in The Festive Wreath (Manchester: Bradshaw & Blacklock, 1842) (Chetham’s Library, 8.J.5.70).

Poetry as an art form can have an emancipatory effect, both on readers and the poets themselves: both are offered a glimpse into a new world and new way of communicating in the poetic style, expanding the world outside of the confines of everyday life. The modern activist idea that ‘the personal is political’ encapsulates how everyday occurrences amount to the way society treats you and the life you lead. The poetical can be included here. Not only can the content of a poem be personal—and therefore political—or vice versa, but in writing poetry, the labouring class poet used their personal time for not just a creative but a political way, harnessing their free time to personal creation rather than creation to boost the economy. The disbelief that Mancunians could produce anything other than cotton—expressed by individuals such as John Stanley Gregson in his Gimcrackiana (1833), of which we have a copy in our collection—encapsulates the political agency that poetry represented as a means to imagine Mancunians as something other than cogs in a machine.

Whether or not John Critchley Prince saw himself as a reformer, his poem ‘Buckton Castle’ grounded this tension between the personal, political and poetical. In lines 109-116, Prince wrote:

‘Ye who in crowded town, o’ertoiled, o’erspent,

For bread’s sake cling to desk, forge, wheel, and loom,

Come, when the law allows, and let the bent

Of your imprisoned minds have health and room;

So ye may gaze upon the free and fair,

Receive fresh vigour from the mountain sod’

In this stanza, Prince explored the effects of city life on the labouring class. He evoked the Romantic view of the liberating quality of nature as a place for respite, encouraging the labouring class to escape the cramped city, breathe in the fresh air, and take a break. Like the act of writing poetry, this was time taken to express oneself and explore a different life. With his heavy workload, it is unlikely that Prince and other labourers would have much leisure time, but poems like such as these helped imagine a new future for the labouring class. Although much of the poem focused on the beauty of the area, the eponymous Buckton Castle is a medieval ruin, and its remnants may have reminded the reader that the great structures that signified wealth and power—like the factories that towered over the Sun Inn—could fall.

Figure 2: The view from Buckton Castle (photograph by Richard Nevell, 2009).

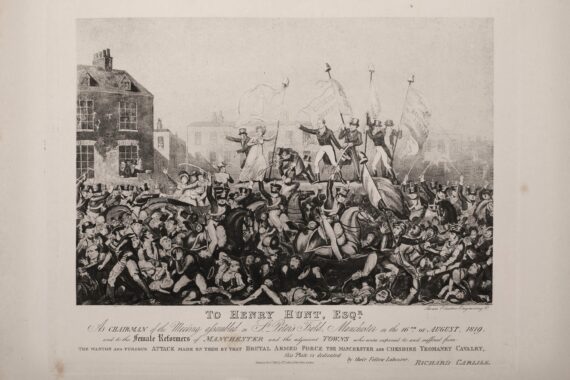

The influence of the Romantic movement is undeniable in the works of the Sun Inn poets. Romanticism promoted a return to nature, seeking the sublime, and detested the man-made and the industrialisation of society. Many Romantic poets, such as Shelley and Wordsworth, came from affluent backgrounds, and enjoyed lengthy educations and the leisure time to reflect and write poetry. As was mentioned in one of our recent blog posts, collections of Romantic poetry were more expensive and harder to come by in the north of England. Romantic writing was often concerned with the imprisonment of man’s mind, and called for liberation and equality, values that were shared with Chartism. Indeed, Shelley wrote ‘The Masque of Anarchy’ inspired by the Peterloo Massacre, at which Samuel Bamford (another member of the Sun Inn Group) was present. Prince wrote in his sonnet ‘On Receiving From a Friend the Poems of Keats’ that:

‘Oh! thou hast pleased me to my heart’s content,

And set my jarring feelings all in tune.

‘Twere sweet to lie upon the lap of June,

Half hidden in a galaxy of flowers,

Beneath the shadow of impending bowers,

And pore upon his page from morn till noon.

‘Twere sweet to slumber by some calm lagoon’

In this sonnet, Prince demonstrated the transformative effect of poetry, the that comfort it provided and the creative capability of the labouring classed in Manchester. In exploring the way that he found himself moved by Keat’s language, Prince felt that it ‘‘twere sweet to slumber by some calm lagoon’. In writing about being transported to this idyllic moment of rest and beauty, we see the importance of reading poetry within labouring class communities, which helped one dream of a better life.

The first wave of workers to flock to Manchester for job opportunities came from the fields, looking for regular employment rather than seasonal harvest work, and rural life and the natural world were frequently praised in poems by the Sun Inn Group. Like the Romantics, they looked back on what they saw as a simpler, ‘purer’ time and way of life, and mourned what they felt was being lost as factory work and machines came to define the working lives of the common man. On the other hand, poetry also reveals class divides and the struggles of labouring class poets; the Sun Inn Group were regionally known, but were restricted in their artistic success. Prince, for example, relied on the patronage of others in order to complete his work, and still laboured six days a week alongside his writing. Classist ideas and the time taken up working or facing persecution from the authorities were barriers to poetry’s emancipatory effect.

Figure 3: An engraving depicting the Peterloo Massacre (Chetham’s Library, 12.F.3.21, np).

The oral poetic tradition lent itself to the poetry of the labouring class, and the Sun Inn played an important role in the poetic scene of nineteenth century Manchester. As a public house, the Sun Inn functioned as a ‘third space’ for the labouring class to gather and share ideas and poetry, free from industrial obligations. In sharing their poems aloud, the Sun Inn Group exemplified the oral tradition as an accessible art form, since the need to be able to read was obviated. Although Chetham’s Library was something of an exception, most libraries were not open to all, and as the Peterloo Massacre of 1819 demonstrated, protests and ideals of Chartism were not welcomed by the authorities. The Sun Inn therefore played a crucial role in the expression of the labouring class, since their opinions and art found a home in this spaces. Charles Swain’s poem ‘Poor Man’s Song’ began:

‘Oh! better be poor and be merry,

Than rich as a lord and be sad;

For good beer laughs louder than sherry,

Which never such happy friends had!’

Through this ballad-like poem, Swain demonstrated the community among the labouring class and the unifying nature of public houses, with the energy which he opened his poem with and the direct references to the rich versus the poor. Poetry could be a catalyst for pride in the labouring classes, since it was through poetry that Swain found a way to express this. Just as the Chartist movement helped to create pride and a sense of identity for the labouring class, poems such as ‘Poor Man’s Song’ contributed to a growing collection of literature that reflected the lived experiences and traditions of the working class.

In looking at the economic, political and artistic background to the Sun Inn Group’s lives and work, poetry can be understood as a crucial creative element in the expression of class struggle, raising awareness of the conditions of the working class and the effects of industrialisation on the mind. Although poetry was unable to lift the labouring class out of poverty or vanquish classism, the creative output of the labouring class could help unify the masses, provide an outlet for workers, and put Manchester on the map for artists.

Blog post by Georgia Hathaway

3 Comments

Peter Taylor

Very interesting thanks

Julie Minshull

Thank you 😊

Joanna M Williams

Interesting that the pub figured so largely in this group’s identity, as Chartists as a group tried to discourage alcohol, and to encourage ‘radical tea-drinkings’ instead. This must have created a tension, as many radical groups did meet in pub rooms, and the National Charter Association itself was founded in the Griffin Inn in Ancoats.