- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

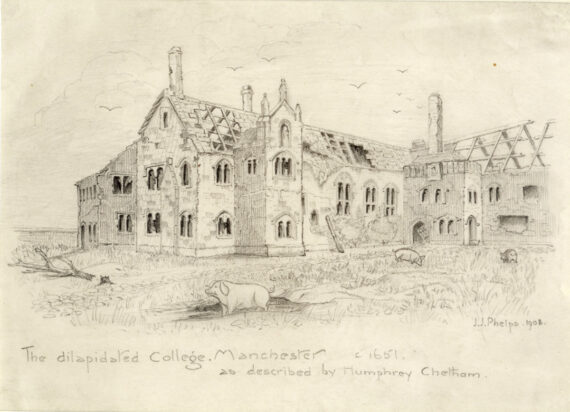

The Dilapidated College, Manchester

One of Humphrey Chetham’s first considerations when making the bequest of a library and school for poor boys upon his death was to find a suitable building in which to house it. Coincidentally, there was a vacant property that would suit these needs: the medieval College House in the centre of Manchester. It was built in 1421 to accommodate a college of priests and remains one of the most complete medieval complexes to survive in the northwest of England. The buildings had been confiscated from the clergy by the Crown in the 1540s, sold to the Earls of Derby, and were again seized by the Parliamentary Commissioners from the Derby estate after the latter supported the royalist cause during the civil war. The beautiful old sandstone buildings, together with the magnificent Library interior, create a unique atmosphere for readers and visitors alike.

However, during Humphrey’s time, the building was not well preserved. The College House, after many years of neglect, was in a poor state. During the Civil War it had been used as a prison and arsenal. Humphrey himself remarked in his letter to Ralph Brideoake, 17 Mar 1648 that ‘the towne swine make their abode bothe in the yards and house’. This letter to Ralph Brideoake inspired a sketch by local artist and assistant librarian at Chetham’s, J.J.Phelps, in 1908 titled ‘The Dilapidated College, Manchester’.

Phelp’s original sketch.

Despite the site being a work in process, Humphrey saw the building’s potential and he specified that it was to be purchased by the executors of his will, who were to go on to provide the body of trustees for his charitable foundation. They carried out his wish and acquired the building after his death in 1653. The restoration of the college was carried out by local craftsmen, and a joiner named Richard Martinscroft was entrusted with the task of fitting and furnishing the Library.

The Library was housed on the first floor in order to avoid rising damp, and the newly acquired books were chained to the bookcases, or presses, in accordance with Chetham’s instructions. Nearly 400 years later the building remains a working library.

3 Comments

Peter Barry Anderton

An amazing story that needs to be told in the City’s schools. That books are the beginning of knowledge and wisdom, and that Humphrey Cheetham was Manchester’s first benefactor.

Peter Barry Anderton

An amazing story that needs to be told in the City’s schools. That books are the beginning of knowledge and wisdom, and that Humphrey Chetham was Manchester’s first benefactor.

Gill Williamson

A remarkable story of vision, tenacity, skill and effort to re-purpose a damaged, heritage building: its low price due to damage probably made it affordable. A story as relevant now as it was then in the home country context – and in due course (I hope) in Afghanistan, Syria and Ukraine.