- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

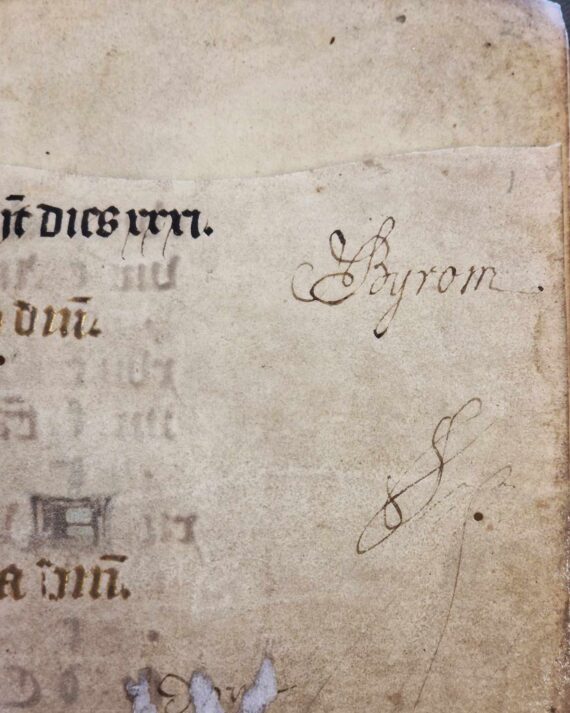

Tinkler, Tailor, Librarian, Thief

For as long as there have been libraries, there have been people willing to steal from them; and as a result, book-owners have always taken measures to prevent theft. From the ancient world into the medieval period, book curses were added to books by their owners, usually invoking divine retribution against would-be thieves. Medieval librarians added ownership inscriptions to institutional books to discourage the same thieves, and, when that didn’t work, they chained the books up so that readers had to consult them at desks. This practice continued into the early-modern period, and when Chetham’s Library was founded in 1653, it followed contemporary trends and chained its books to the shelves. Later, when the chains were removed, gates were added between the presses to keep visitors and readers out, and ex libris bookplates were added to the books to indicate their ownership, again reflecting broader trends in library history.

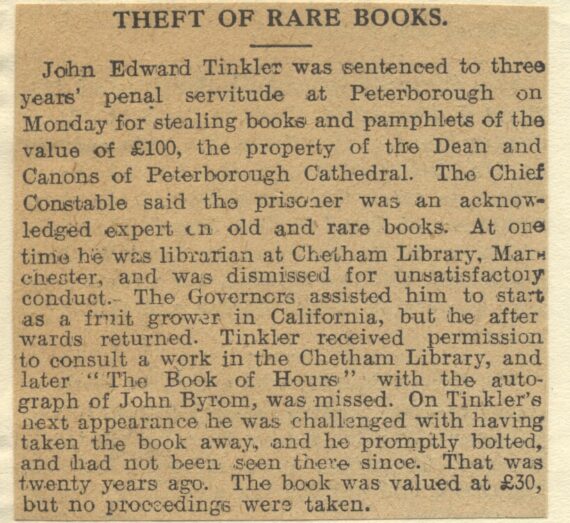

Even despite these precautions, though, theft continued to pose a threat to historic collections, a fact demonstrated by the story of one Chetham’s Librarian. His name was John Edward Tinkler. He was born in 1864, the son of a clergyman from Stamford in Lincolnshire, and sometime around 1882, he became Assistant Librarian at Chetham’s Library. It was here that he seemingly gained his first experience of working with rare books. He held his initial post for three years and was then appointed Chetham’s Librarian, a post he held for two more years. At least in some respects, Tinkler seems to have discharged his duties adequately. In the preface to The fellows of the collegiate church of Manchester (1891), Frank Renaud thanked Tinkler for his assistance; a few years earlier, John Radcliffe had thanked him in the preface to the first volume of his edition of the parish registers of St Chad in Yorkshire (1887). In that volume’s list of subscribers, Radcliffe named Tinkler as librarian; when the second volume was published in 1892, however, Walter Thurlow Browne had replaced him.

Fig 1: Tinkler named as Chetham’s Librarian in John Radcliffe’s The Parish Registers of St Chad, Saddleworth, vol. 1 (1887).

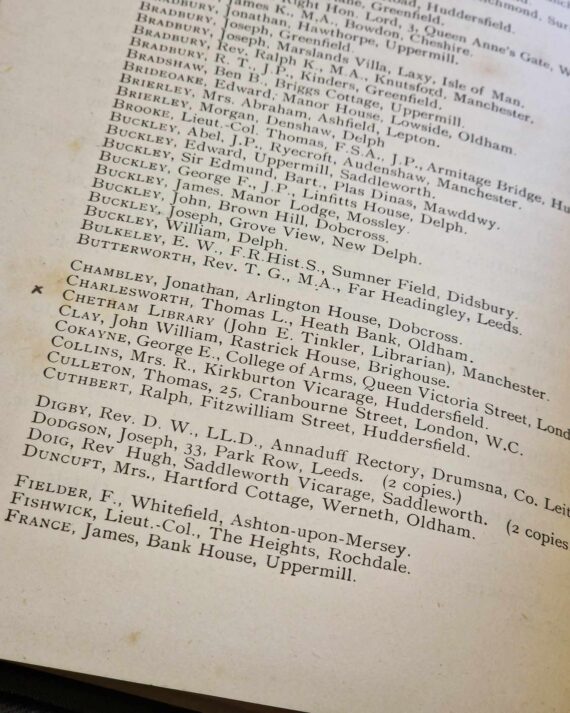

The reason for Tinkler’s departure was his dismissal by the feoffees on account of his unsatisfactory conduct. Two years after he had taken up the librarianship, Tinkler was caught using Chetham’s stationery to conduct suspicious dealings with rare books dealers in Berlin, Munich and New York, buying and selling books and pocketing the profits. When they dismissed him, the feoffees covered the liabilities that he had incurred out of a sense of duty, and – perhaps in an attempt to keep him as far away as possible – they helped set him up as a fruit-grower in California. Nevertheless, five years later, Tinkler was back; he gave the feoffees two hundred pounds to cover part of his debt and requested and received permission to consult the collections again. This proved to be a mistake, however, when a Book of Hours bearing the autograph of the Manchester poet John Byrom went missing. When he next visited the library, Tinkler was challenged by Browne and promptly fled. Inexplicably, no proceedings were taken against Tinkler, and the book was not recovered.

Fig 2: Byrom’s autograph in another Chetham’s Library Manuscript (shelfmark).

Tinkler nevertheless found himself before the London sessions in 1904, accused of stealing books; he was convicted and sentenced to fifteen months in prison. While there, he was convinced by his fellow inmates to steal yet more rare books, this time from the library of Peterborough Cathedral, which was then undergoing restoration. At the time, the library was kept in a room above the porch on the west front, and Tinkler managed to gain access to it multiple times; he later boasted that he had a skeleton key that would open any church door in England. He sold the books he stole from the library to rare book dealers in England and America; when his buyers enquired where he obtained the books, he would tell them that he had bought them from an old library in Kent, or else from a gentleman in London. Tinker approached the London bookdealers through an accomplice, Arthur William Champion; Tinkler told Champion that he had debts that prevented him from approaching the London dealers himself. The two men regularly met in pubs to discuss the business, and Tinkler mentioned his trips to America to sell books.

Fig 3: Peterborough Cathedral’s front porch, with the former library above.

Eventually, in 1909, the thefts came to the attention of Peterborough Cathedral’s dean, Arnold Page, when he noticed a loose leaf from one of the cathedral’s books on the library floor. He realised that books were missing, and reported the theft to the police; when the library’s contents were checked against its catalogue, it was discovered that 215 rare books and pamphlets had been stolen, mostly valuable Americana. A list of the missing books was printed and quietly circulated among the involved parties, and in December 1910, a warrant for Tinkler’s arrest was issued. It was not until 6 February 1912 that the police caught up with Champion, and through him, Tinkler: Detective Inspector Vermer accompanied Champion to a pub where he was to meet Tinkler, and informed him of the warrant against him. At first, Tinkler was nonchalant: he declared that he had never been to Peterborough, but that he would assist the police as best he could. He was nevertheless charged with the theft of the books; on 22 April he appeared for trial at the Peterborough sessions, where he was found guilty by the jury and sentenced to three years’ penal servitude.

After Tinkler’s arrest, around fifty of the stolen books were identified as Peterborough books through their distinctive eighteenth-century inscriptions and shelfmarks, which Tinkler had unsuccessfully attempted to erase with chemicals. Some of the stolen books were traced to America; it was discovered that one had been sold to the American financier and collector J. P. Morgan (whose son founded the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York) for a four-figure sum – at least £95,000 today – and another had been sold to another collector for a similar value. Such impressive sums underline Tinkler’s excellent knowledge of rare books and the book trade, without which he could not have been as successful as he was. Two quotes from Tinkler’s trial encapsulate the dichotomy he represented: he was, at once, ‘the quintessence of cunning and the incarnation of a book thief’, and ‘one of the greatest experts in old and rare books living’. Tinkler’s story is perhaps the most ignominious of any Chetham’s Librarian but it is tempting to wonder what he might have achieved if he had kept on the straight and narrow so many years before at Chetham’s Library.