- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

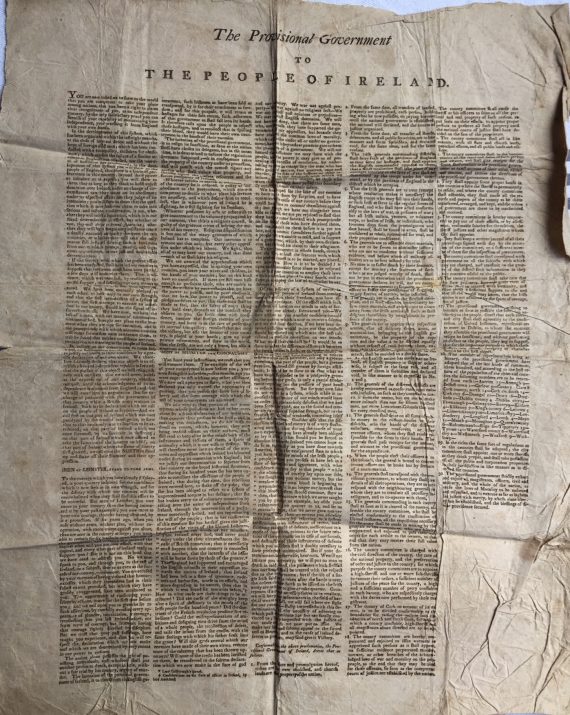

A Rare Piece of Irish History

Among the treasures of the Heywood archive is a single-sheet broadside that would be easy to overlook. Yet the item, entitled The Provisional Government to the People of Ireland, is one of the most significant documents in the history of Irish nationalism and also one of the rarest Irish revolutionary documents extant.

In 1803 in Dublin, Robert Emmet and a small band of republican revolutionaries proclaimed the independence of Ireland. After a haphazard rebellion, that turned out to be little more than a calamitous, bloody riot on Dublin’s Thomas Street, his hopes lay in ruins. Emmet, after fleeing to a safe house in the Wicklow mountains, was subsequently arrested, tried for treason and put to death along with 15 of his followers.

As part of the preparations for his rebellion Emmet wrote this proclamation addressing it from “The Provisional Government to The People of Ireland”. It began by reiterating republican sentiments expressed during the previous rebellion of 1798 and calling on the Irish population to claim their right to independence: “You are now called on to show to the world that you are competent to take your place among nations, that you have a right to claim their recognisance of you, as an independent country … We therefore solemnly declare, that our object is to establish a free and independent republic in Ireland: that the pursuit of this object we will relinquish only with our lives … We war against no religious sect … We war against English dominion.” The Proclamation not only served as a call to arms but also as an interim constitution and is remarkably forward thinking in terms of constitutional law. In addition to democratic parliamentary reform, the 1803 Proclamation announced that tithes were to be abolished and church lands nationalised. The lines “we will not imitate you in cruelty; we will put no man to death in cold blood, the prisoners which first fall into our hands shall be treated with the respect” predates the first Geneva Convention by 60 years, which is considered today as the basis on which rest the rules of international law for the protection of the victims of armed conflicts on the treatment of prisoners of war.

Due to the destruction and suppression of the proclamation it never fully received the status and acknowledgment as the hugely important historical document that it is. It provided inspiration for Pádraig Pearse in writing the 1916 Proclamation and summed up Emmet’s remarkable opinions, some of which could be described as too modern to be accepted or understood in 1803.Approximately 10,000 copies of the proclamation are reputed to have been secretly printed on Emmet’s orders on 23 July 1803, but the British authorities went to great efforts in order to ensure that its content was suppressed and they were nearly all destroyed.