- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

A Tale of Two Statues

In our Library newsletters recently we’ve been taking a look at items from the series of 101 Treasures in our collections, and today’s blog post, taking the minute book of the Albert Memorial Committee of Manchester as its starting point, will focus on the Albert Memorial in Albert Square and the Cromwell statue now in Wythenshawe. It will explore the history of the statues and the connection of these figures to Manchester.

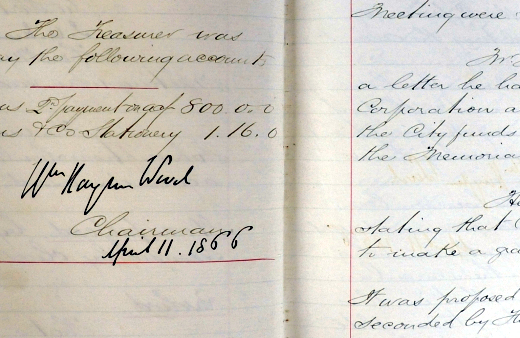

A detail from the minute book of the Albert Memorial Committee, which was given to the Library by Colonel A.F. Maclure in 1924

Prince Albert was the husband and consort of Queen Victoria from their marriage on 10th February 1840 until his early death (possibly from typhoid fever) on 14th December 1861. Although the couple were initially unpopular in some circles, Albert went on to be remembered because of his public support for various humanitarian causes. His first public speech, in June 1840, was given to the Society for the Abolition of Slavery, he took an active interest in the reform of child labour, broadly supported free trade over the Corn Law interest, and supported the Society for Improving the Condition of the Labouring Classes. While we might see many of these interventions as against the expected political neutrality of the royal family and entourage in our own age, the contrast with the Georges or William IV’s political approaches is striking. In addition, Albert was a patron of the arts, science, trade, and industry. His dedication to these areas culminated in the Great Exhibition of 1851 which drew public attention and appreciation to these areas both in England and abroad.

What is perhaps less well known is Albert’s specific connection to the city of Manchester. For example, in 1857 Albert firmly supported the Art Treasures Exhibition in Manchester. This was a display of fine art and photography held in Manchester and remains the largest art exhibition held in the UK. It attracted millions of visitors and went on to influence the display of numerous art collections in England. Albert and Queen Victoria lent the greatest number of art objects to the exhibition. Albert even travelled to Manchester to open the exhibition on 5 May. Following this, renowned sculptor Matthew Noble (1817-1876) donated a marble bust of the Prince to Manchester.

The Albert Monument in its entirety, with Worthington ‘s canopy and architectural framing in a photo prepared for the minute book

Albert remained a popular figure in Manchester until his death, when it was decided an appropriate memorial should be created in Mancheser to commemorate him. A practical memorial such as a hospital or a School of Art was initially considered. However, Thomas Goadsby, the Mayor of Manchester, offered to donate £500 to finance the creation of a statue of the prince on the condition that it be housed in a “proper temple” somewhere in the city. The rest was publicly funded which is a testament to Albert’s popularity in the area. Noble reprised his role as sculptor of the statue and Manchester architect Thomas Worthington created the enclosing shrine. The monument was completed in 1866.

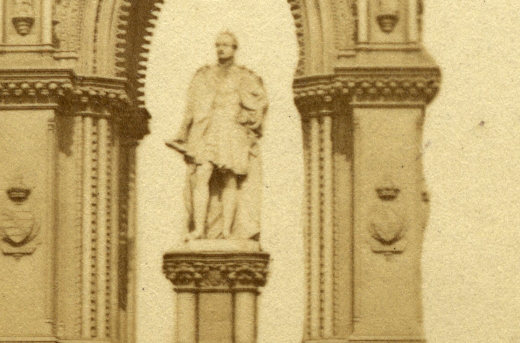

Matthew Noble’s statue itself in close up

As well as being positive commemorations, monuments and statues can also prove controversial. This brings us to the second statue of the post which is that of Oliver Cromwell now located in Wythenshawe. There are some interesting parallels between the two statues. For example, Matthew Noble also created a bust of Oliver Cromwell at the same time as he sculpted the bust of Albert for the Exhibition of 1857. Noble was to put aside his work on the creation of a full-length statue of Cromwell in order to concentrate on completing the statue for the Albert Memorial.

During this period Oliver Cromwell was viewed as a champion of Public Reform by liberal radicals including Manchester railway king and free trader Edward Watkin. This opinion was shared by Manchester Mayor Thomas Goadsby, who supported the idea for his commemoration in the 1860s. Upon Goadsby’s death his widow Elizabeth would continue the petition for a statue. At the time societal views regarding Cromwell differed greatly. This division would be revealed once the statue was unveiled in 1875.

Cromwell’s statue prominently placed next to Manchester Cathedral (right of shot) and providing somewhere to sit while failing to impress Queen Victoria

Oliver Cromwell was the former Lord Protector of England, Scotland and Ireland after the British Civil Wars (1642-1651). He came to power after the victory of the Parliamentarians and dissolution of the monarchy in 1649. Cromwell was a controversial figure, in part due to massacres of Royalist garrisons in Wexford and Drogheda during his final military campaigns in Ireland, continuing oppression in Ireland, and a regime of harsh public reforms at home. As a result, he has been a ‘marmite’ figure in history, seen by some as a champion of liberty and regarded as a seventeenth-century tyrant and butcher by others.

Cromwell had local as well as national significance as both symbol and historical figure. Manchester was besieged by Royalist forces under the future Lord Derby during the Civil War and became a successful parliamentarian stronghold, with Chetham’s Baronial Hall and buildings acting as a prison and munitions store.

When she visited Manchester, it was noted that Queen Victoria was less than impressed with the presence of the statue of her ancestor’s killer prominently and pointedly sited close to the west door of the Cathedral that she, as head of the Church of England, was bound to visit. Cromwell’s likeness was relocated – perhaps we might say exiled – in the 1980s to Wythenshawe Park whilst inner city developments were taking place. This was appropriate as Wythenshawe Hall was where Parliamentarian forces besieged a Royalist garrison under Robert Tatton in the winter of 1643. The monument still divides opinion today, and was recently sprayed with less than complimentary graffiti in September 2020.

Cromwell rusticated to Wythenshawe park, prior to informal re-captioning.

As the Christmas holidays approach, we might remember that if we had listened to Oliver there would be no holiday, no break and no celebrations either religious or secular.

2 Comments

Peter Ward

It wasn’t exiled in the 1980’s. I visited this statue in the 1970’s at Wythenshawe park. I have a photo of me Aged 5 in these steps which would have been 1977.

Mrs C. M. Lowe

A very interesting post as I had no knowledge of Cromwell’s association with either Manchester or Wythenshawe! I always considered myself as a Royalist, and thought of Cromwell as a miserable and harsh reformer. However, it’s likely that his input in history has provided a necessary balance to the God-given sovereignty that prevailed beforehand.

It’s also a very fine statue!