- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

A Woman’s Write: Searching For Chetham’s Published Women

Visitors to the library have been asking the same question for some time “Are there any books written by women”. Whilst the answer has been yes, it has often been hard to provide a definite example as women’s contribution as authors or as participants in the book trade have often been hidden behind a veil of anonymity or behind masculine names for a variety of reasons. As a result, we have been doing research to uncover their stories, culminating in our latest theme and display for visitors: A Woman’s Write: Searching For Chetham’s Published Women. You can see this display on one of our popular tours of the Library and ancient buildings, which you can book online.

Our archives and store rooms on the ground floor house the work of many female poets, artists, novelists, explorers, and scientists. However, most of these were published and acquired by the Library after the 1850s, when explicit female authorship was becoming slowly more accepted by later nineteenth-century society. As a result, such works can be found by author name in our catalogue with ease. This was not to say there were not still bars in place both before and after this period.

For example, in the 1840s the Brontë sisters were using the pseudonyms Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell. Charlotte Brontë was to address this in the preface to the 1850 edition of her sister Emily’s Wuthering Heights, explaining why they felt the need to hide their names, assuming it would be easier to get into print if publishers believed they were male. With this constraint considered, it is not surprising that the works that feature on the historic first floor book shelves of the Library, largely printed before 1800, contain many pseudonyms concealing women’s involvement in book production, both as writers and in the book trade. Many of these books are both religious and academic texts, areas in which women’s involvement and engagement was less expected still, and in which women writers would have represented an eyebrow-raising exception to the rules of contemporary societies.

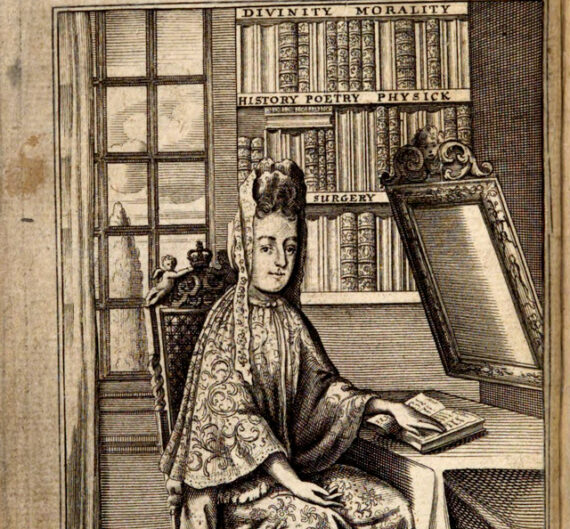

Portrait of Aphra Behn (1640-1689) by Peter Lely

In creating this display, we hope to shed light on Chetham’s earliest works published by women, and by doing so, share the stories of those women who fought to get their voices heard. Over the next few months to complement the exhibition we will be writing a series of detailed blog posts about these women and their achievements.

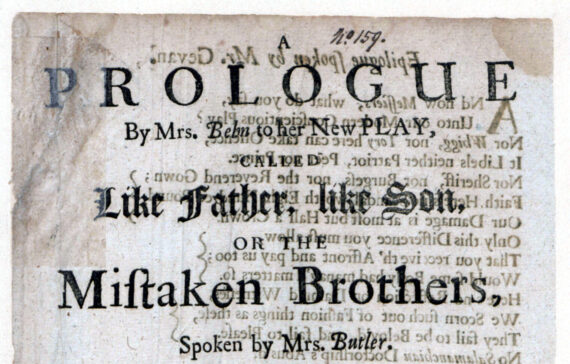

One woman whose work can be found on the first floor of the Library is Aphra Behn (1640 – 1689), one of the first English women to earn her living by writing plays, and who was employed by Charles II as a spy in Antwerp. She was part of a small circle of poets and famous libertines of the 17th century such as John Wilmot, Lord Rochester.

Detail from A prologue by Mrs. Behn to her new play, called Like Father, like son, or The mistaken brothers, spoken by Mrs. Butler, 1682. Chetham’s Library, Halliwell-Phillips Collection.

Work by another woman of note in the Library’s collection is that of Anna Maria van Schurman (1607-1678) a Dutch painter, engraver, poet, and scholar. She was a true Renaissance woman fluent in fourteen languages, excelling in art, music, and literature. She was the first woman to study at a Dutch university, although her unofficial status there was underlined by the fact that she had to sit behind a screen so as to be unseen by her male fellow students.

1649 portrait of Anna Maria van Schurman by Jan Lievens

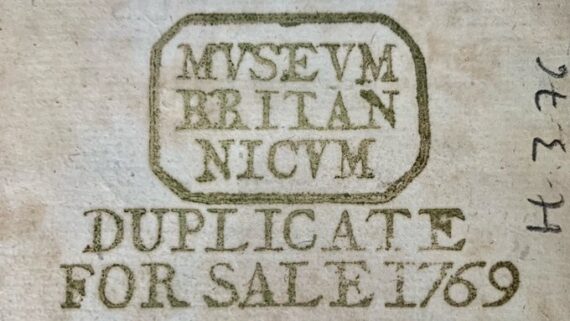

Our copy of her Euklēria, or The Choice Of The Better Part is interesting as it is stamped “Museum Britannicum Duplicate for sale 1769” indicating her work was in circulation in establishments such as the British Library in the 18th century.

Example of the British Museum duplicate stamp in our copy of Anna Maria van Schurman’s ‘Euklēría, or Choosing the Better Part’.

We also have a book by Mary Brunton, a Scottish novelist, who was interested in philosophy and was in favour of women learning ancient languages and mathematics. Her novels often broke the social etiquette of Georgian society and have been praised by Fay Weldon as ‘rich in invention, ripe with incident, shrewd in comment, and erotic in intention and fact.’

Portrait of Mary Brunton (1778-1818) from the 2nd edition (1820) of Emmeline.

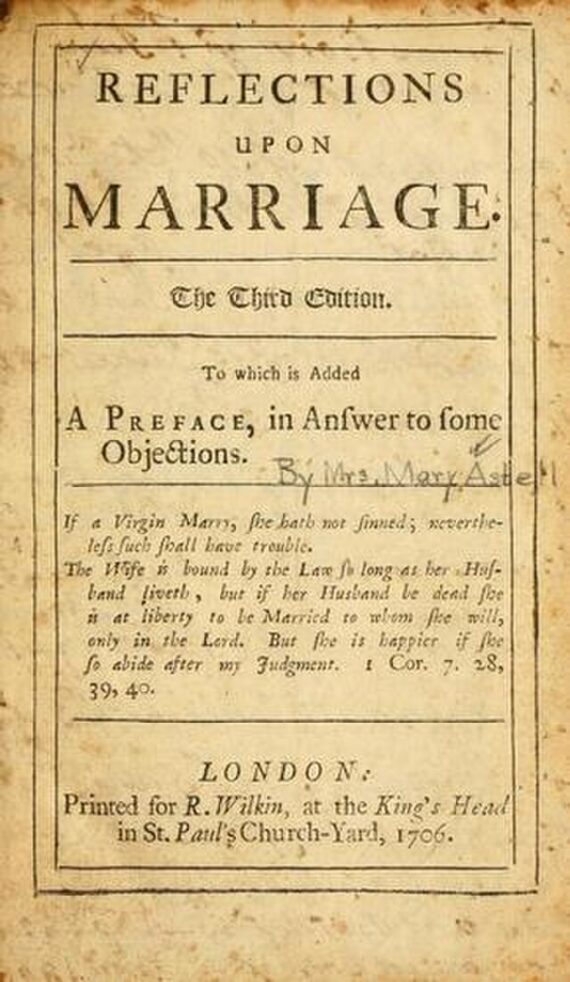

Mary Astell, a feminist writer whose work is also on the Library shelves, was a philosopher from Newcastle known as ‘the first English feminist.’ Writing anonymously, Astell advocated the view that women were just as rational as men, and just as deserving of an education, and suggested the idea of an all-female college in her A serious proposal to the ladies, for the advancement of their true and greatest interest of 1694. In the anonymously issued Some Reflections on Marriage, Astell warned women of the dangers of hasty or ill-considered marriages, advising that marriage should be based upon a lasting friendship.

Title page of the third edition of Reflections upon Marriage by Mary Astell ( (not our copy, which is missing the title-page).

Sophia Brahe (1559 – 1643) was a Danish noblewoman proficient in astronomy, chemistry, and medicine. She and her brother Tycho Brahe worked together making astronomical observations. She assisted with a set of observations on 11 November 1572, which led to the discovery of the supernova, now called SN 1572. She also made observations on the 8 December 1573 lunar eclipse. She is credited by name in our copy of Inscriptions from Hafnian Latin, Danish and Germanic: together with inscriptions from the Amagers of Uraniburgic and Stellaeburgic, as well as two epistles, one sent by Tycho Brahe to Peucerum, the other by his sister Sophia Brahe.

Portrait of Sophia Brahe.

These are just a few of the women who have left their mark in the Library and throughout history. To find out more about women in the Library please book on a guided tour and visit the display.

3 Comments

Michael Norton Schmidt

An excellent initiative.

Harriet Grubb

This is a really interesting article, and one that we discuss often where I work at Buxton International Festival. Our books director has recently written an article on how non-fiction writing women are still today very often under-represented. That aside, I’m getting in touch about Vera Brittain, the author of the best selling war memoir of Testament of Youth. Her account of being a young woman in the run up to, and during WW1 is often heralded as one of the few books to give the women’s perspective. We have a new musical at the festival about her early life. Here’s a link with more information. https://buxtonfestival.co.uk/whats-on/the-land-of-might-have-been. Would it be possible for you to help us spread the word about this event, and the story of this remarkable local lady?

Thanks

Harriet

ferguswilde

Hi Harriet, I’m sorry, we missed the opportunity due to a technical issue with our blog site. I hope the performances went well, Vera was certainly a remarkable person.