- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

An English Renaissance Feminist: Cancelled

Above: Portrait by Lady Mary Wroth, by John de Critz 1620.

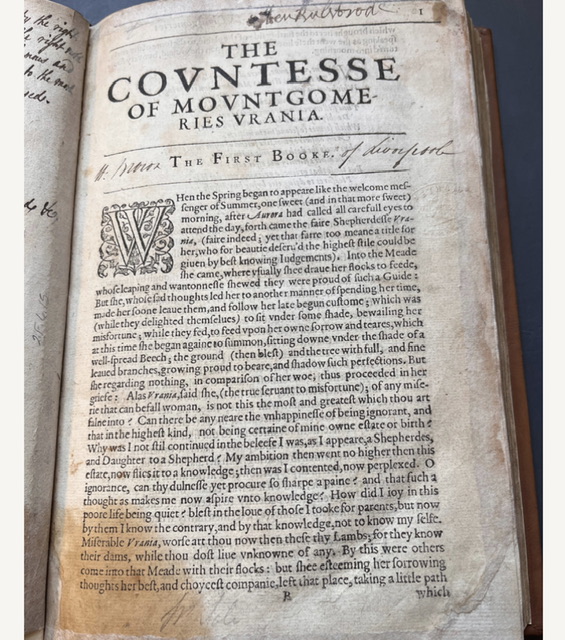

Just before International Women’s Day 2023, there emerged from the shelves of Chetham’s Radcliffe collection a rare copy of The Countesse of Montgomeries Urania, published in 1621.

Beyond the unassuming cover lies the first romance or novel written by an English woman. The very circumstances of its publication are intriguing. John Marriott and John Grismand, publishers, entered Urania into the Stationers’ Register on 13th July 1621, a mere three days after they had been released from the Marshalsea prison, having been fined for promoting an allegedly scurrilous poem by George Withers. Publishing was, then as now, a risky business.

This volume looks innocent enough, and even dull, but 5 months after it was released its author was writing to the Duke of Buckingham to ask for a warrant to have any sold copies withdrawn; she seems to have been intent on cancelling herself. It is possible she did not intend it for publication since there was an aristocratic stigma against those, especially women, who circulated their work in print. But in her letter requesting its withdrawal she blamed ‘strong constructions that have been made of my book’ that were ‘as far from my meaning as is possible.’ Urania appears to have been a succès de scandale.

Chetham’s Library copy of Urania.

Who was this woman who disregarded convention to the point of endangering her reputation? Mary Sidney was a contemporary of Shakespeare and bright star of the Elizabethan court. She was born in 1587 into a literary and political family which included the poets Sir Philip Sidney (her uncle), Mary Sidney (her aunt) and Robert Sidney, the Earl of Leicester (her father), Sir Walter Raleigh was also a first cousin. Mary herself was not only a scholar but an accomplished musician and dancer. After Queen Elizabeth’s death she became a close associate of Queen Anne, the wife of James I, for and with whom she sang and danced in popular masques.

This glamorous young girl was married at the age of sixteen by arrangement, as was the custom of the time, to Sir Robert Wroth, well-connected, a sportsman, but allegedly a spendthrift, gambler and drunkard; it was said that he hunted while she danced. She was already eminent enough to have several literary volumes dedicated to her by the time she was in her twenties, the only book worthy of her husband’s patronage was a Treatise On Mad Dogs.

Within a few months he was complaining to her father of his wife’s demeanour towards him. Ben Jonson, although praising Wroth publicly, wrote that Mary was ‘unworthily married on a jealous husband.’ Although Wroth did refer to Mary in his will as his dear and loving wife, his death from gangrene in 1614, followed by the death of their only son, meant that Mary was deprived of property and heavily in debt.

Either before or after her husband’s death, Mary began an affair with the married William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, her first cousin and childhood friend with whom she shared a passionate interest in art and literature. This time the liaison was Mary’s own choice, even though Herbert was said to be ‘immodestly given up to women.’

One of Herbert’s mistresses, Mary Fitton, has been suggested as a model for the Dark Lady of Shakespeare’s sonnets, and Herbert himself has been claimed by some to be the Fair Youth. All did not end well for Mary Wroth; soon after she left the court as a result of the Urania scandal Herbert appears to have abandoned her, never acknowledging the two children they had together.

William Herbert was not a self-effacing man. His statue outside the Bodleian Library in Oxford celebrates his generous gifts of manuscripts, books and money.

Bronze statue of William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke (1580–1630) in front of the main entrance to the Old Bodleian Library. Photo by Frank Schulenburg.

By 1621 Mary was well-known and respected for her poetry and for Love’s Victory, a pastoral ‘closet drama’ to be read rather than performed, in which four different couples are paired up, each signifying a different kind of love (flawed, chaste, comic and true). She had already transgressed traditional boundaries by writing in a secular vein, with an emphasis on female agency and desire. Now, in Urania, she produced a complex romance in 400,688 words, ending with a sequence of sonnets and with almost a thousand characters, hundreds of intersecting tales, mostly about love, though also incorporating political themes.

The central story is of Queen Pamphilia’s love for her cousin, the Emperor Amphilanthus, whose name means ‘lover of two.’ Pamphilia, Greek for ‘all-loving’, takes pride in her constancy to him, even as he repeatedly becomes entangled with other women. Though the references are coded, this is thought to echo Wroth’s own love for Herbert. She used her vivid imagination to fictionalise the world she knew, often adding melodramatic flourishes to real events, and including songs and poems as part of the story.

When Urania was published, some elements of aristocratic society would have rejected the book as shameful gossip by a woman whose error consisted of writing a book containing her thoughts. She was criticised by some powerful noblemen for depicting their private lives under the guise of fiction and was accused of ‘taking great liberty … to traduce where she please.’

Edward Denny, Earl of Norwich, who claimed to recognise his family in Urania, accused her of slander in a satiric poem, calling her a ‘Hermaphrodite in show, in deed a monster’, and declaring ‘Thy witt runs madd not caring who it strike.’ She fired back with her own poem, later suppressed, calling him a ‘lying wonder.’ Other men, however, praised her work. Henry Peacham named her ‘an inheritrix of the Divine wit of her immortal Uncle’, while Ben Jonson lauded her in a sonnet, and claimed that by copying her works he not only became a better poet, but a better lover. There is evidence that other aristocratic women writers read and commented on Urania, at the time of its publication and later in the 17th and early 18th century.

Women of any class in the time of Mary Wroth were expected above all to be silent and obedient, as illustrated in contemporary religious works, legal treaties and literature. Mary was a radical in her time merely for writing a work intended for public consumption, since the act of composing a novel violated the ideal of female virtue. She was a pioneer in freely adapting a traditional romance form to accommodate the experience and perceptions of a Jacobean woman. In mixing fact and fantasy the text draws attention to contemporary issues, such as the hitherto unquestioned ‘traffic’ in women, who were acquired and exchanged as the property of men. Urania is now in the 21st century seen as a valuable text for feminist readings of the early modern age, providing insights into the complex and often contradictory nature of women’s place and role in society.

Chetham’s library edition of Urania is one of only twenty-nine surviving 17th century copies. It remained out of print until the appearance of a scholarly edition in 1995. Our 1621 copy is unusual in that it does not include the elaborately drawn frontispiece by the engraver Simon van de Passe, which depicts the ‘Throne of Love’, an idealised vision of relations between the sexes.

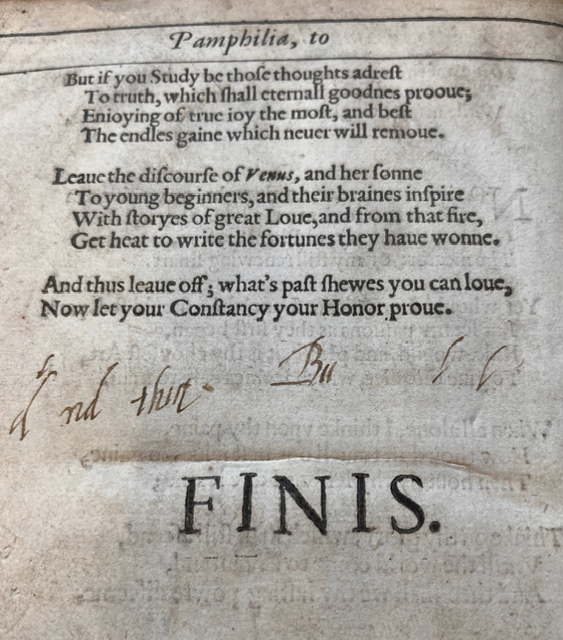

There remain some uncertainties about Mary Wroth’s intentions for her book. Although it is named in honour of her friend, Susan Vere, the Countess of the title, none of the seventeenth-century copies includes the usual commendation by friends, or author’s dedication or letters to readers. The end of each of the first two parts of the book are marked with an elaborate printer’s ornament and announcement, but strangely there is no definitive conclusion; at the end of Part 3 Wroth breaks off the happy ending in mid-sentence (all things are prepared for the journey, all now merry and contented and nothing amisse; griefe forsaken, sadness cast off; Pamphilia the Queene of all content; Amphilanthus joying worthily in her; And …) The printer has left the last page blank, perhaps in the hope that he might eventually receive material to complete the volume.

Chetham’s copy begins with a handwritten inscription: The Countesse of Montgomeries Urania written by the Honourable the Lady Wroath: Daughter to the right noble Robert Earle of Leicester and Neece to the ever famous and renowned Sr Phillip Sidney knight ; and to ye Most Exelent Lady Mary Countess of Pembroke late deceased. Unlike the novel, the sonnets have a definitive ending. Mary Wroth went on to compose a second volume of Urania between 1620 and 1630, running to a mere 240,000 words, half the size of the first part. It survived only in manuscript until its publication in 1999.

Chetham’s Library copy of Urania.

This sequel generally follows a second generation of characters descended from those that appear in the first volume, and it occupies a world stage, containing epic encounters between Christianity and Islam. This, together with the first Urania, Love’s Victory and 105 sonnets, comprise the canon which has enjoyed a dramatic increase in interest in the last twenty years and is the subject of international scholarly debate. Mary Wroth lived privately and worried by debt until her death in 1651 or 1653 (documents disagree). How differently might her life have turned out if she had not found it necessary to withdraw from public life after the launch of Urania!

By Kath Rigby