- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Authors and Readers in Humphrey Chetham’s Parish Libraries

Since my last blog post on the Gorton Chest Library back in February 2019, I have made considerable progress in analysing the books in its collection, and I’m pleased to be able to share some of it with you here.

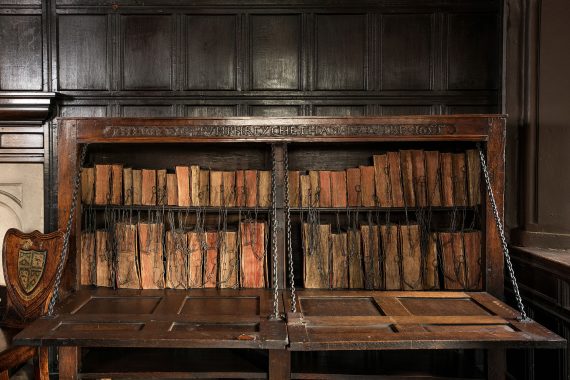

When Humphrey Chetham died in September 1653, he bequeathed £200 to found five parish libraries that were to be placed in Manchester Collegiate Church (now the Cathedral) and Bolton Parish Church, as well as the chapels of Gorton, Turton and Walmsley. Chetham had a personal connection to all of these locations. The £200 was divided between the libraries according to the size of the church: the bigger the church, the more money it was allocated. Manchester Collegiate Church was allowed £70, the parish church in Bolton was given £50, the chapels of Gorton and Turton were allotted £30 each, and Walmsley, the smallest of the five and the only library that never seems to have reached completion, was allocated £20 for purchasing books.

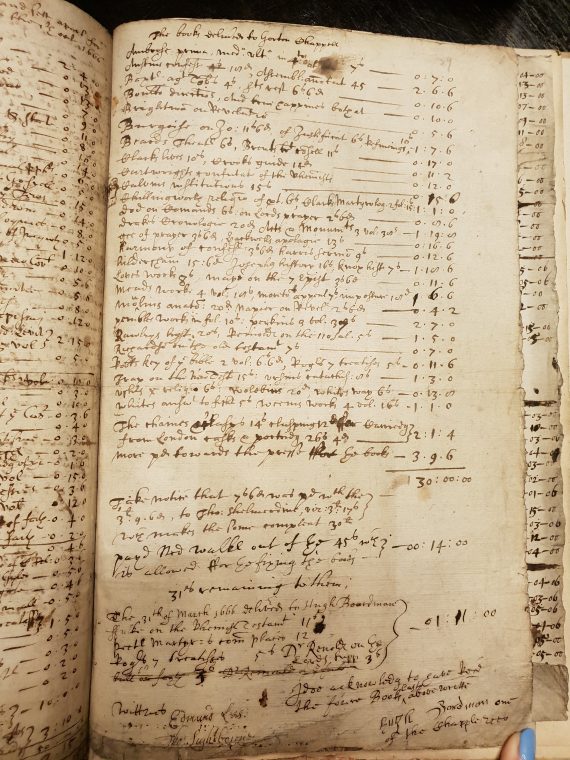

The will stipulated that the books had to be written in English, and of a ‘godly’ nature. The trustees of Chetham’s Library kept invoices that recorded the titles of the books they bought, how much each of the books in for the parish libraries cost, and the date they were delivered to Manchester from the bookseller in London. One invoice, detailing the books that were sent to the Gorton Chest Library, can be seen below.

Just a quick flick down the lists will show you works by key Protestant authors like Isaac Ambrose, Richard Baxter, Thomas Cartwright, John Dod, John Calvin and Arthur Hildersam. These were core Protestant texts that show us that the aim of library is to educate people in this religion, improving their relationship with God and their spirituality. Each of these books included messages to their readers that they were supposed to read, understand and apply to their everyday lives in order to make them better people, and better Protestants. They were purchased with one goal in mind: the spiritual and religious education of the laity.

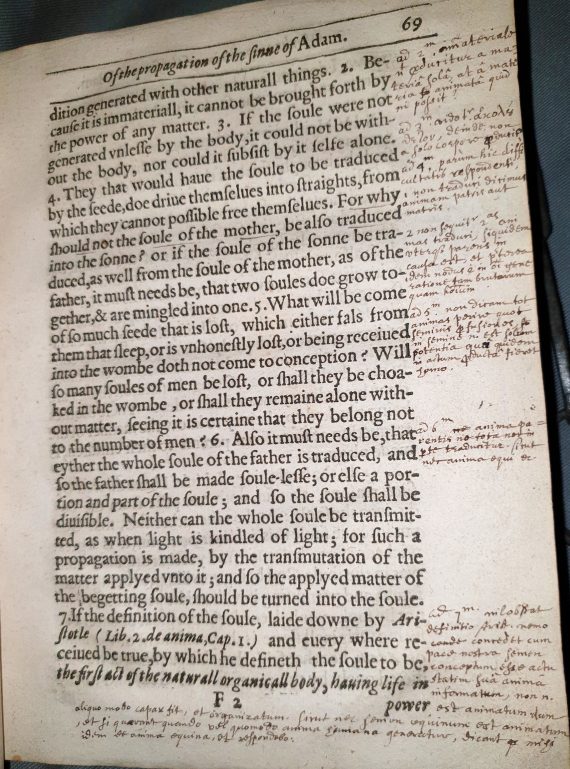

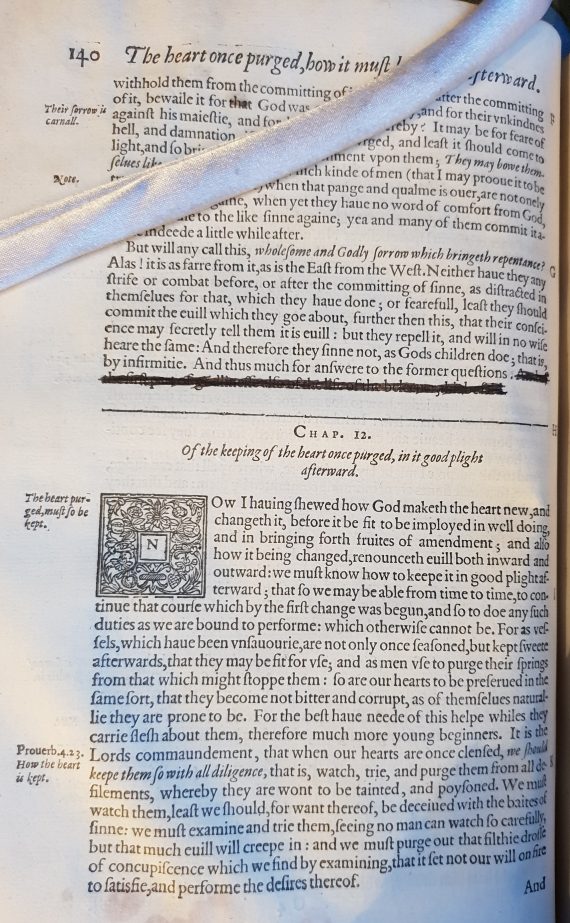

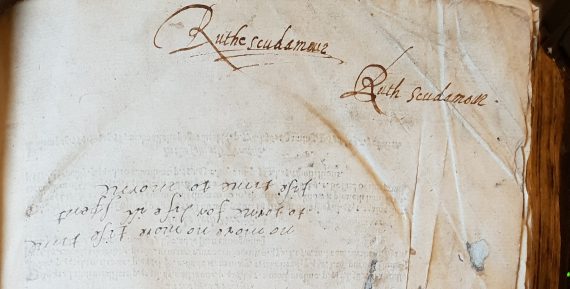

We can often tell what early modern readers thought of their books by looking at the notes and marks they made in them, known collectively as marginalia. The books in the Gorton Chest and Chetham’s other parish libraries were bought second-hand, so we have no way of knowing whether the libraries’ users made the marks in the books. Even if they didn’t, and the marks were made before they were bought and put into the libraries, the marginalia remain an important feature, as they would have impacted on how the later readers understood the messages within the books. Some examples of the different kinds of annotations – and the name of a previous owner/reader, Ruth Scudamore – can be seen in the images below.

Readers of the books now in the Gorton Chest Library were seemingly very interested in the topics of sin and the desire to live a godly life in preparation for death. Readers of Richard Rogers’s Seven Treatises highlighted the idea that people have no power to remove their own sin and that they should repent and put their trust in God to lessen their sins. The whole point of a godly life, was to make a good death and achieve salvation. Authors like William Perkins, whose works are included in Gorton’s collection, urged his readers to actively practised their religion through the exercises of faith, repentance and obedience to God, and in one of his books, a reader has underlined Perkins’s statement that people should do ‘everyday while he is living that which he would do when he is dying’ as the surest way of achieving salvation and entry into heaven.

The marginalia tells us that these books were read closely, and understood and interpreted in a way that demonstrates both the applicability of the texts to people’s own lives, but also the commitment of the reader to the kind of moral and behavioural code that was a prerequisite of the godly living necessary for salvation.

Written by Jess Purdy