- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Bodies In The Library: A display of anatomy books

Humphrey Chetham’s vision for his library was that it would offer resources to the professional men of Manchester (lawyers, clergy, doctors) comparable with those at the university colleges of Oxford and Cambridge. From the start, medical books were an important part of the library collections and our current display shows a small selection of the many anatomy books which were acquired.

To fully understand the anatomy and workings of the human body, to teach medical students about it and indeed to publish anatomy books, the essential requirement is having a dead body to dissect. As medical science evolved, the demand for bodies for dissection far exceeded the supply. The problem was that for most cultures and religions, there had always been a taboo against human dissection-cutting open a dead body was desecration.

Burke and Hare, the body snatchers: Revolting crimes / by Regd. B. Jones

A common solution was to use the bodies of criminals (who were presumably felt to have no human rights) although demand was such that by the nineteenth century the gruesome ‘trades’ of grave robbing and body snatching became financially rewarding (e.g. the notorious case of Burke and Hare in 1828). As part of an attempt to control the trade in corpses, the 1832 Anatomy Act in England made unclaimed bodies, including those of the poor who died in workhouses, available to anatomy schools.

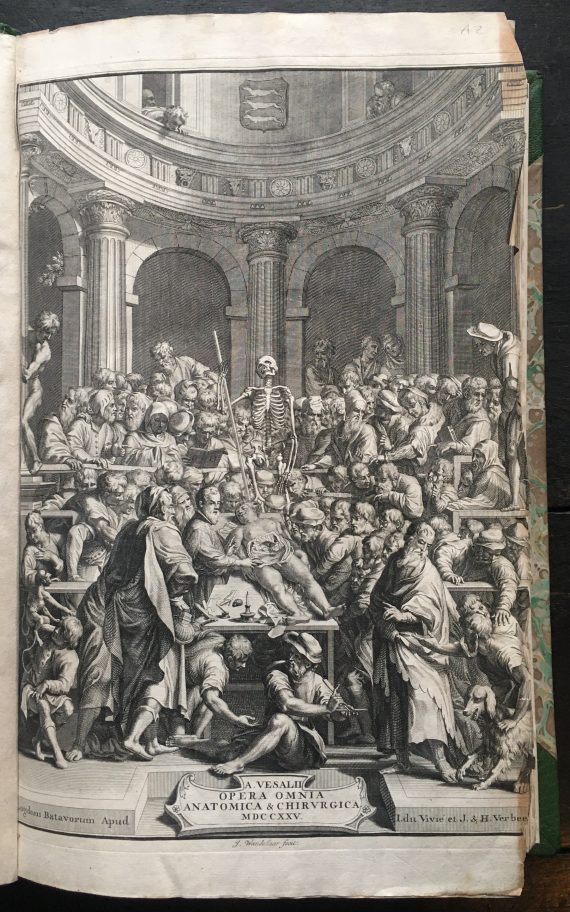

The reality of dissection in the past was undoubtedly brutal. Dissections were ‘performed’ in front of an audience in an anatomy theatre. Natural decomposition meant that a dead body (cadaver) was only suitable for dissection for three or four days following death. After this, the stench as it decomposed became too much to bear, particularly in warm weather. The order of dissection was determined by the rate of decay of body parts: the abdomen was first, followed by the contents of the chest, the brain and finally the limbs.

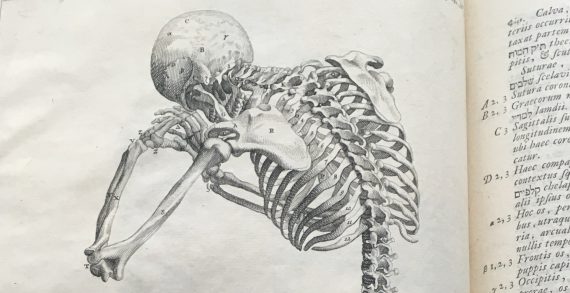

On the anatomy of the human body, De humani corporis fabrica, Andreas Vesalius 1725

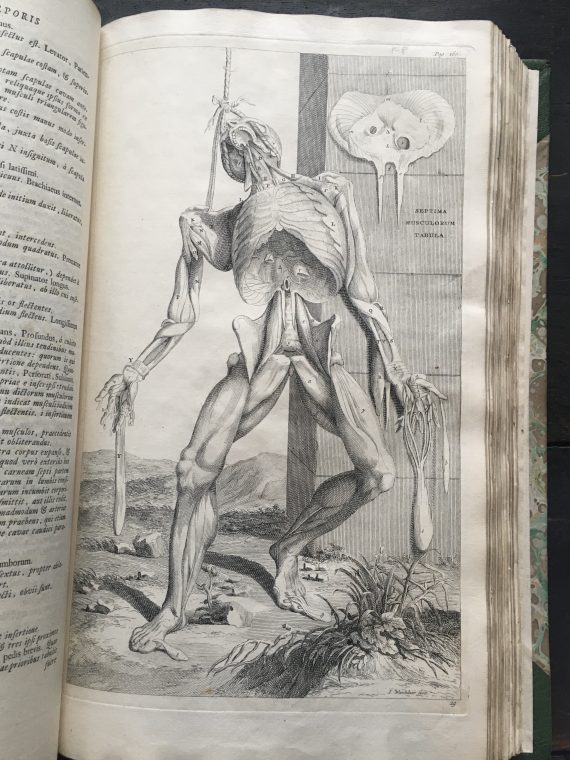

Art and anatomy have been closely connected for centuries. Renaissance artists like Michelangelo and Leonardo studied the human body to enhance their painting and sculpture. Leonardo records that he conducted more than 30 dissections. For obvious reasons clear, accurate illustrations were very important in anatomy books aimed at doctors and surgeons.

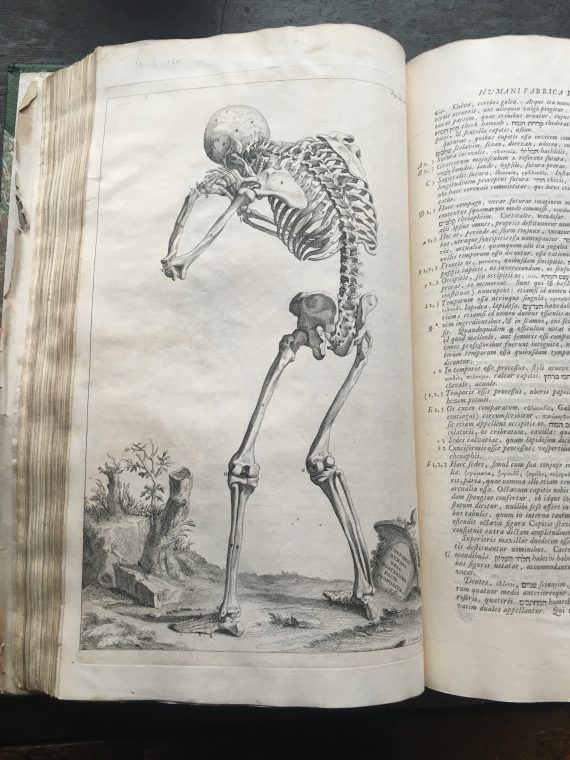

Certainly the most ‘artistic,’ and possibly the most celebrated, book on anatomy is De humani corporis fabrica (On the fabric of the human body.) by Andreas Vesalius first published in 1543. Vesalius was a young medical professor at the University of Padua, famed for his radical, new approach to teaching anatomy.

De humani corporis fabrica, Andreas Vesalius 1725

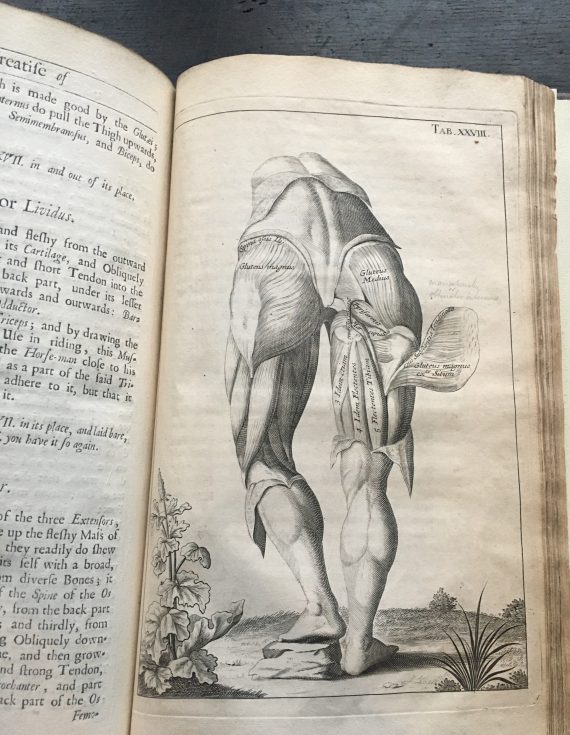

His book was illustrated with stunning woodcuts, allegedly produced from the workshop of the renowned artist, Titian. The most striking aspect of the images is the series of ‘ecorches’ or ‘flayed men’, posed like classical statues in landscape settings, but with their skin peeled away to display their muscled bodies. Our copy is a much later edition from 1725, the images are copper plate engravings based on the original woodcuts but not quite as powerful. The market for illustrated anatomy books grew quite rapidly in the century after the publication of ‘De humani corporis..’ and its dramatic visual style had a huge impact on the design of subsequent works.

John Browne, in 1697, published a book with the very lengthy title of ‘Myographia nova: or, A graphical description of all the muscles in humane body, as they arise in dissection. Distributed into six lectures; at the entrance into every of which, are demonstrated the muscles properly belonging to each lecture now in general use at the Theatre in Chyrurgeons-Hall, London; and illustrated with one and forty copper plates, accurately engraved after the life, with their names on the muscles, as much as can be expressed by figures: as also, with their originations, insertions, uses, and divers new observations of the authors, and other modern anatomists…..’

It is clearly based on the Vesalius work, although the illustrations are far less elegant. Browne was originally a ships surgeon and had his arm fractured by a cannonball in the war against the Dutch. He became surgeon-in-ordinary to Charles II, later working at St Thomas hospital, London. He was a well educated man, seems to have been a good surgeon and his book sold well. However, it was actually plagiarised, illustrations and all, from two other books – William Mollins’ Myskotomia and Guilio Casserio’s Tabula anatomicae.

Myographia Nova, John Browne 1697

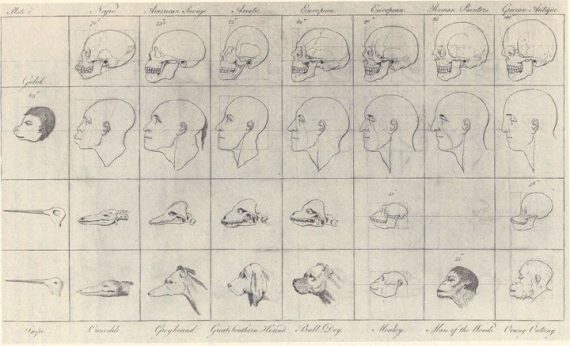

One of the other books on display has a local connection. ‘An account of the regular gradation in man …’ published in 1799 is by a Manchester doctor, Charles White. An able and innovative surgeon who made significant contributions in the field of obstetrics, and was a founder of the Manchester Royal Infirmary, and of a very progressive ‘lying-in’ charity with a hospital to assist poor women which eventually became St Mary’s hospital in the city. White also lectured on anatomy and became interested in the relationships and development of different human races. This book is a collection of the lectures he gave on this subject and, although he condemns slavery in this work, his theories are now regarded as being examples of ‘scientific racism’.

The library has copies of several of Dr White’s publications, two of which have inscriptions “For the publick library at Manchester from the author”. It seems highly possible that, just over 100 years after the library was created, Dr White had been using this library for his research in just the way Humphrey Chetham had envisaged.

‘An account of the regular gradation in man, Charles White 1799

Blog written by volunteer Patti Collins

4 Comments

Karen Cliff

Very enjoyable and informative blog. Thank you for writing and sharing it.

ferguswilde

Thanks, Karen! Glad you enjoyed it, we’ll be sure to let the writer know.

Dorcelin Mcatamney

This is a very interestng find indeed! Thank you for sharing it to us.

ferguswilde

Glad you enjoyed it, thank you!