- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Bright hopes for suffrage: Lydia Becker and the struggle for democracy

Teresa May with her hands tied behind her facing a spike-gloved Angela Merkel in a boxing ring, the shadow cabinet as a panicking Dad’s Army led by ‘Captain Corbyn’ wearing a Lenin cap, Nicola Sturgeon as the Loch Ness Monster. As the UK general election approaches, cartoons are cutting through and subverting campaign ‘spin’ to influence and amuse us.

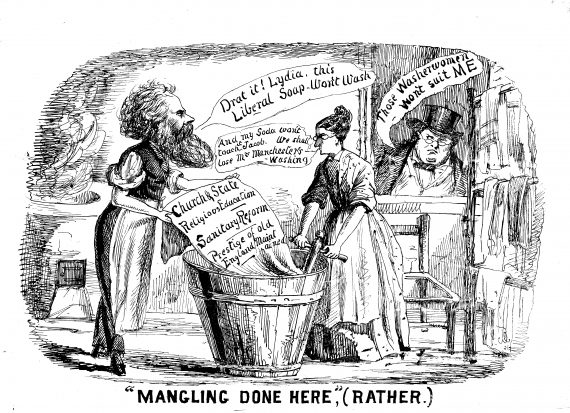

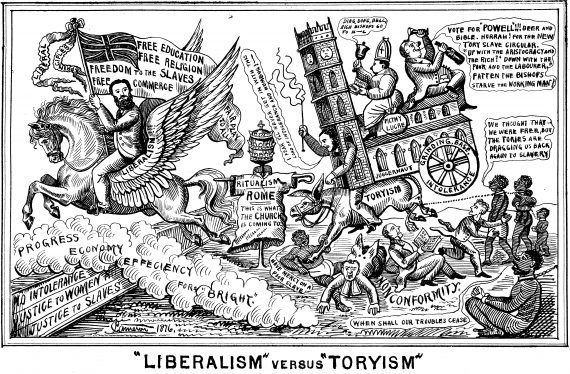

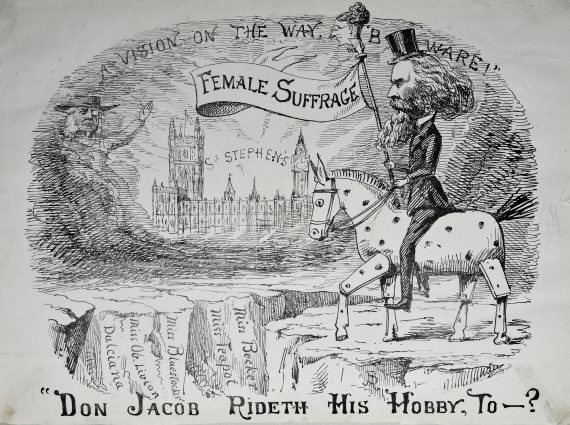

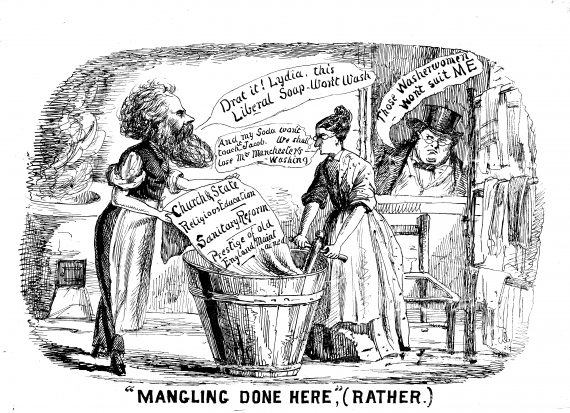

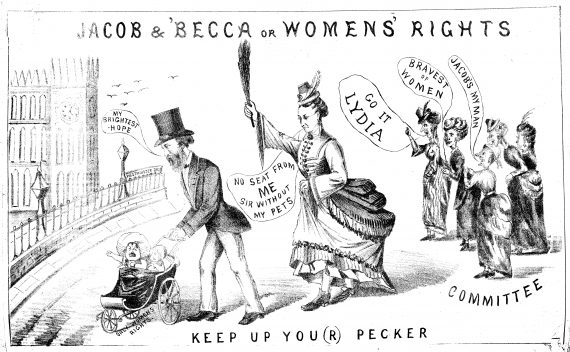

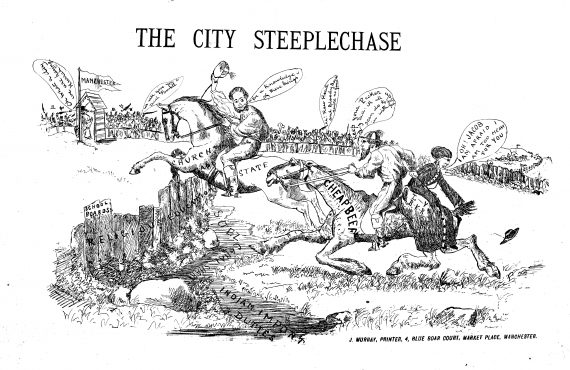

Political cartoons, a feature of political life since the early 18th century, provide visual commentaries on political personalities, policies and passions. The library holds many examples, from Hogarth’s social satires to more recent works. One set lampoons the 1868 general election campaign in Manchester, a city which was enfranchised by the 1832 Reform Act then gained a third MP through the Representation of the People Act in 1867. Jacob Bright stood as a Liberal candidate against the Tories in 1868 on platform of social justice and women rights alongside his friend Lydia Becker, a fearless campaigner for women’s suffrage. These rather crudely drawn cartoons offer us insights into the election issues of the time, many of which resonate today.

Jacob Bright was a radical from a Quaker family of politicians, activists and reformers and a passionate suffrage campaigner. He was influenced by Ursula Bright, his wife, and Priscilla Bright Mclaren, his sister, both staunch supporters of women’s enfranchisement, as well as by his friend Lydia Becker. The 1832 Reform Act had extended the franchise to men owning property worth 10 shillings or more, extended again in 1867 to all male householders in the boroughs as well as lodgers who paid rent of £10 a year or more. Disgracefully, men who did not meet the property qualification and all women remained disenfranchised. Bright ‘… brought it into all his speeches, much to the annoyance and even dismay of some of his staunchest supporters. “Jacob is at it again!” some really affectionate friend would whisper: and it was true. He was always “at it”‘(Manchester Guardian).

Jacob Bright was a radical from a Quaker family of politicians, activists and reformers and a passionate suffrage campaigner. He was influenced by Ursula Bright, his wife, and Priscilla Bright Mclaren, his sister, both staunch supporters of women’s enfranchisement, as well as by his friend Lydia Becker. The 1832 Reform Act had extended the franchise to men owning property worth 10 shillings or more, extended again in 1867 to all male householders in the boroughs as well as lodgers who paid rent of £10 a year or more. Disgracefully, men who did not meet the property qualification and all women remained disenfranchised. Bright ‘… brought it into all his speeches, much to the annoyance and even dismay of some of his staunchest supporters. “Jacob is at it again!” some really affectionate friend would whisper: and it was true. He was always “at it”‘(Manchester Guardian).

Cartoons of the time warned against women gaining rights, often through mocking or cruel depictions of suffrage campaigners. Lydia Becker was a Manchester radical and prominent campaigner for women’s suffrage. In January 1867 Lydia convened the inaugural meeting of the Manchester Women’s Suffrage Committee, the first organisation of its kind in England. On 14 April 1868, Becker was one of the speakers at the first public meeting of the National Society for Women’s Suffrage in the Free Trade Hall in Manchester where she moved a resolution that women should be granted voting rights on the same terms as men. She founded the Women’s Suffrage Journal which she published from 1870 until 1890.

Many years before women won the vote, Becker supported Lilly Maxwell, a Manchester shopkeeper, to vote in the 1867 by-election in Manchester. Lilly was a ratepayer whose name had been included on the Manchester register of voters in Manchester by mistake. Lydia accompanied her to Chorlton Town Hall where the returning officer allowed her to vote, as a loophole in the act granted all ratepayers the right to vote but failed to exclude any specific gender. After this success, Becker immediately began encouraging other women heads of households in the region to apply for their names to appear on the electoral rolls, but the government quickly stopped this, declaring women’s suffrage illegal in 1868.

Lydia Becker and Jacob Bright ‘s agitation for women’s suffrage attracted public scorn and cartoonists ridiculed them. The view of many at the time that women had no business speaking up at all in public, and certainly not to demand their rights, meant that women suffragists came in for particular disparagement. Lydia Becker was not conventionally beautiful and the cartoons exploit this by exaggerating her dumpy physique, her hairstyle, pointed nose and round wire rimmed glasses. This emphasis on their lack of ‘femininity’ was meant to serve as warning about the threat to the established social order and position of women to deter potential supporters.

Lydia Becker and Jacob Bright ‘s agitation for women’s suffrage attracted public scorn and cartoonists ridiculed them. The view of many at the time that women had no business speaking up at all in public, and certainly not to demand their rights, meant that women suffragists came in for particular disparagement. Lydia Becker was not conventionally beautiful and the cartoons exploit this by exaggerating her dumpy physique, her hairstyle, pointed nose and round wire rimmed glasses. This emphasis on their lack of ‘femininity’ was meant to serve as warning about the threat to the established social order and position of women to deter potential supporters.

Bright was elected to parliament where he continued to campaign actively for women’s suffrage, becoming leader of the suffragists in the house in 1868. He introduced a suffrage bill to extend parliamentary suffrage to all women but MPs rejected this. He did, however, succeed in 1869 in moving an amendment that secured women the right to vote in municipal elections.

By the time of Lydia Becker’s death from diphtheria in 1890, at the age of only 63, her tireless campaigning had strengthened the resolve of suffragists, but had yielded no concessions from government. Equal voting rights for women lay still nearly thirty years away, and it took the shock of the suffragettes and the far greater shocks of the Great War economy finally to lever open the door to democratic participation.

More than a century later, we can turn our backs on the parodies of Becker as a hatchet-faced termagant and thorn in the flesh of John Bull, and see a real Manchester pioneer emerge.

2 Comments

Michael Howard

This is marvellous – Ghislaine (Howard) and I are working with Greater Manchester Chamber of Commerce – 151 Elliot Street, to help further recognition of Lydia Becker’s achievement. It does seem as if recognition she deserves, though late it coming, is on its way. More information coming soon on her website.

ferguswilde

We’re pleased to hear that! Do be in touch if we can help – you can find us from https://library.chethams.com/about/contact-us/ Pleased to hear the Chamber of Commerce is involved too.