- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Matilda Betham: An (un)Celebrated Woman

Above: Matilda Betham, unknown artist, image taken from Wikimedia Comms.

Mary Matilda Betham (known as Matilda to her friends and family) was a diarist, poet and author in the last years of the eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth. She had a keen interest in women’s rights, which was reflected in her numerous writings. Like many of the individuals whose works are included in Chetham’s Library’s new exhibition, A Woman’s Write, her life highlights the difficulties faced by women who tried to publish during this period.

Like her fellow author and contemporary Jane Austen, Matilda was the daughter of a rector. Born in 1777 to Reverend William Betham and his wife Mary (née Damant), she was the eldest of fourteen children. William Betham was himself an author, having written and published works on royal genealogy and the English baronetage. From a young age Matilda exhibited an interest in history and literature, reciting poetry and reading plays and histories. She educated herself in her father’s extensive library under his occasional tutelage, although she also received instruction in sewing to prevent a ‘too strict application to books’. During visits to London she learnt to speak French, and she later learnt Italian from Agostino Isola in Cambridge.

Unfortunately, Matilda’s growing family faced severe financial hardship. Driven by a sense of duty, Matilda left the family home and took to painting miniature portraits to support herself. While in London she was encouraged to pursue her talents by her uncle Edward Beetham, whose family was closely involved in literary and artistic circles. Matilda received instruction from the portraitist John Opie, who was tutoring her cousin Jane Beetham, and was encouraged by her uncle (himself a publisher) to realise her literary ambitions. It was around this time that Matilda developed an interest in women’s rights, and she began to ‘rally and argue about the equality of the sexes’. In 1797 she published her first work, Elegies and Other Small Poems, for which she received praise from her family, her friend Lady Charlotte Bedingford, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who wrote to her in 1802, comparing her to Sappho (another poet featured in ‘A Woman’s Write’) and encouraging her to continue writing. Between 1804 and 1816, Matilda exhibited her portraits at the Royal Academy of Arts.

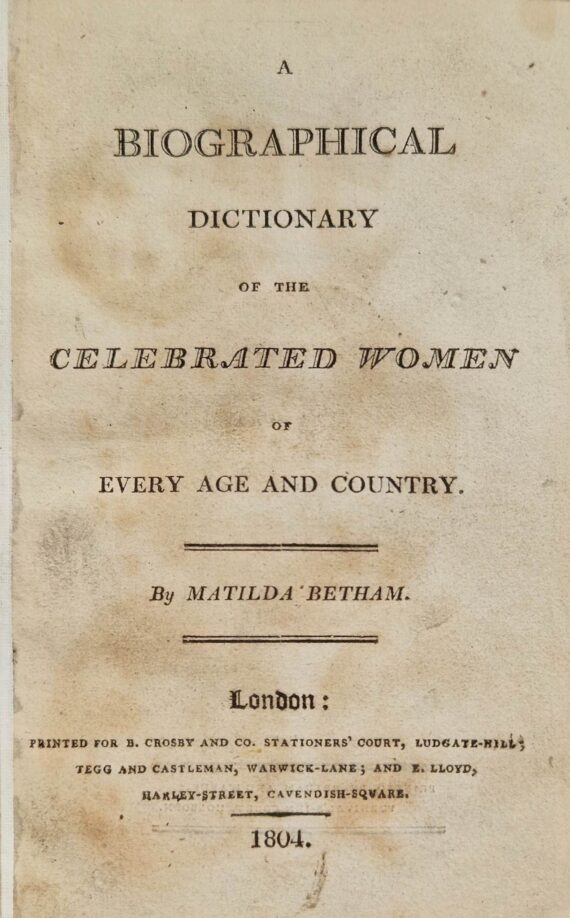

Matilda published her second work, A Biographical Dictionary of the Celebrated Women of Every Age and Country, in 1804. The result of six years’ research, it included short biographies of women who were ‘distinguished by their actions or talents’, including Cleopatra, Boadicea, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Marie de France (a medieval poet), Anne Boleyn, Elizabeth Elstob (an early Anglo-Saxon scholar) and Marie Antoinette. A copy of this work can be found in Chetham’s Library, although we know relatively little about how it got here besides the fact that it was acquired before 1862. It is the only work of Matilda’s to have entered the library.

Above: The title page of Chetham’s Library’s copy of Matilda’s A Biographical Dictionary.

In the years that followed, Matilda’s literary career flourished. She published a second book of poetry in 1808 and several shorter works anonymously in magazines, and gave public recitals of Shakespeare in London. In 1816 she published the Lay of Marie, a poem with scholarly appendices, inspired by the life of the medieval poet Marie de France. This poem was Matilda’s best-received work, but its publication was beset by difficulties. Advertisements for the poem misspelt both the heroine’s name and its author’s, many of the printed books were damaged by mildew, and the costs of publishing and advertising the work drove Matilda into severe financial hardship. Forced to abandon her literary career, she returned to the country and tried to support herself by painting miniature portraits again, hindered by the shabby state of her clothing. She later recalled sleeping in room without furnishings or a bed, keeping herself warm by covering herself with old clothes. In 1819, she was placed in a mental asylum by her family.

Matilda was released the following year. She claimed that she had suffered a ‘nervous fever’ due to the stresses of publishing the Lay of Marie, and that she had been unjustly committed without any sort of examination or treatment. Following her release she returned to London and kept her address secret from her family. She received financial assistance from the Royal Literary Fund and returned to her literary pursuits, directly championing women’s rights. In a letter to the MP John Cam Hobhouse, she urged him to continue working for ‘general suffrage’ in parliament to improve women’s conditions. In 1821 she published A Challenge to Women, which defended Queen Carolina against the charges of adultery levelled against her and called on women to support her by signing a petition. The following year she was once again committed to the asylum by her family, but she continued to pursue her literary ambitions after her release. She published Sonnets and Verses in 1836, and A Dramatic Sketch in 1838. However, she also suffered from several setbacks. Her play Hermoden, written in the late 1830s, was lost and was never published. She tried to publish Crow-quill Flights by subscription in the early 1840s, but when the promised money failed to materialise she was forced to apply for additional funding. Many of her manuscripts were lost in a fire, and she was unable to secure copies of poems she had previously sent to her friends; as a result, several of Matilda’s works are now lost. Nevertheless, she maintained a circle of friends into her old age, and a young man of her acquaintance remarked that he ‘would rather talk to Matilda Betham than the most beautiful young woman in the world’.

Above: Portraits of famous women in Matilda’s A Biographical Dictionary.

Matilda died in London on 30th September 1852 at the age of seventy-five. Over the course of her life she had published at least nine works, and won acclaim from those in her literary circle. Her poetry and miniature painting earned her some financial independence, but she nevertheless faced hardship throughout her life. After her death she was included in Six Life Stories of Famous Women and Friendly Faces of Three Nationalities, both written by her niece Matilda Betham-Edwards, but today she is little-known. Hopefully, A Woman’s Write can bring inspirational women like Matilda to light and celebrate their remarkable achievements.

By Emma Nelson.

3 Comments

Richard Kenyon

Fascinating and inspiring!

Avril Jones

I’m ashamed to say that I have never heard of Matilda Betham.

It seems her professional life was marred by the fact that she had no financial safety net, and a personal life littered with family members who must have had shares in asylums.

The main tragedy is that her work was treated so nonchalantly by friends that they couldn’t keep it safe for us to read.

ferguswilde

Thanks, Avril! Yes, I’m afraid hers is a sad tale in many ways. It’s consonant with the historic policies of acquisition at Chetham’s that her biographical work is the only one we possess; poetry and literary works of modern writers were not collected. We’re grateful to Emma for writing this post and giving Matilda some long overdue attention.