- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

No Cure for Love: Two Early Modern Apothecaries and Their Books

Chetham’s Library has no lack of books with famous former owners: there is a copy of Plato’s works owned by the early modern playwright Ben Jonson (see our post on this subject as part of our ‘101 Treasure’s of Chetham’s’ series), a book owned by Elizabeth Gaskell and, of course, the five books annotated by Dr John Dee, scholar and alchemist and warden of Manchester college from 1595 to 1605. The collection even includes books owned by royalty: Matthias Corvinus King of Hungary, Henry VIII and Elizabeth I all owned books that are now in Chetham’s Library. However, less illustrious readers also left their traces, and many of the volumes in the library tell stories of the lives of readers from past centuries. One such example are the books owned by Robert Syddall and John Hartley, two apothecaries living in Manchester in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Not much is known about Syddall and Hartley beyond the evidence they left in their books. The parish registers of Manchester Cathedral show that Syddall was born in the 1570s, married in the early years of the seventeenth century, had a son (also named Robert) and died in 1645, survived by his widow Ellen. An inventory of Robert Syddall’s possessions compiled after his death reveals that he kept equipment necessary for the making of remedies, such as stills and an alembic, in his house, suggesting that he pursued his profession from home rather than from a shop. John Hartley is even more elusive: the parish registers only show that he had three daughters, one of whom survived to adulthood, and that he died in 1667. It is not clear whether Syddall and Hartley knew each other, but it seems likely, given that they were active in the same profession at the same time in what was a relatively small town in the seventeenth century. Thirty books owned by these two apothecaries are now in the collection in Chetham’s Library. Of these, thirteen have ownership inscriptions by both Syddall and Hartley, suggesting that they perhaps came into Hartley’s possession after Syddall’s death.

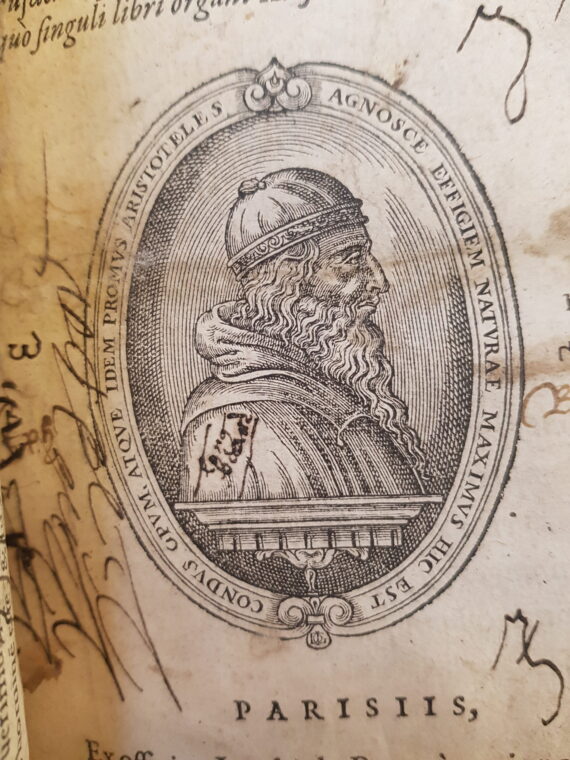

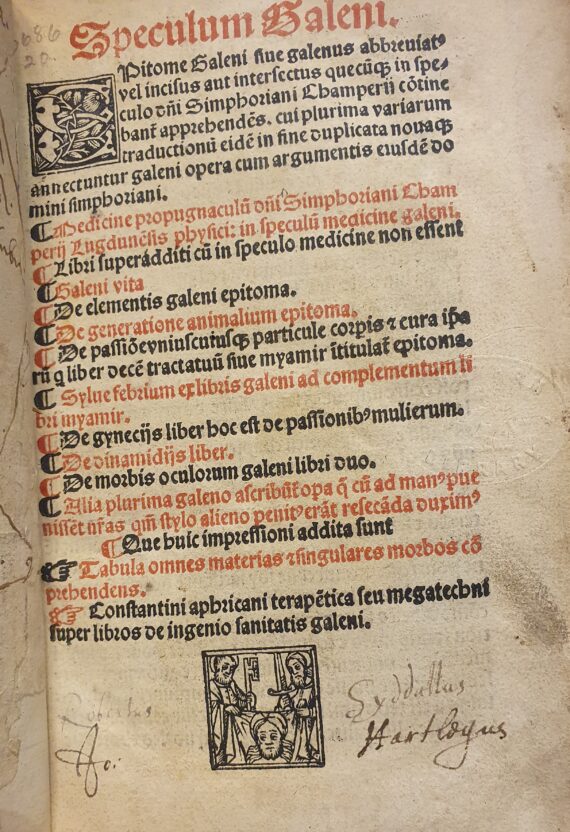

Image 1: Signatures of Robert Syddall and John Hartley in Champier’s Speculum Galeni (BYROM 2.I.3.69)

Ten have inscriptions by Syddall but not Hartley and seven by Hartley but not Syddall. One further volume that belonged to Syddall is now in the British Library (BL Add MS 62127). The books came to Chetham’s Library as part of the Byrom Collection, donated in 1870 by a descendant of the Manchester poet and scholar John Byrom (1692-1763). It is not entirely clear how Byrom acquired the books or who owned them between Hartley’s death and Byrom’s acquisition, but it is probable that they stayed together as a collection from the seventeenth century onwards.

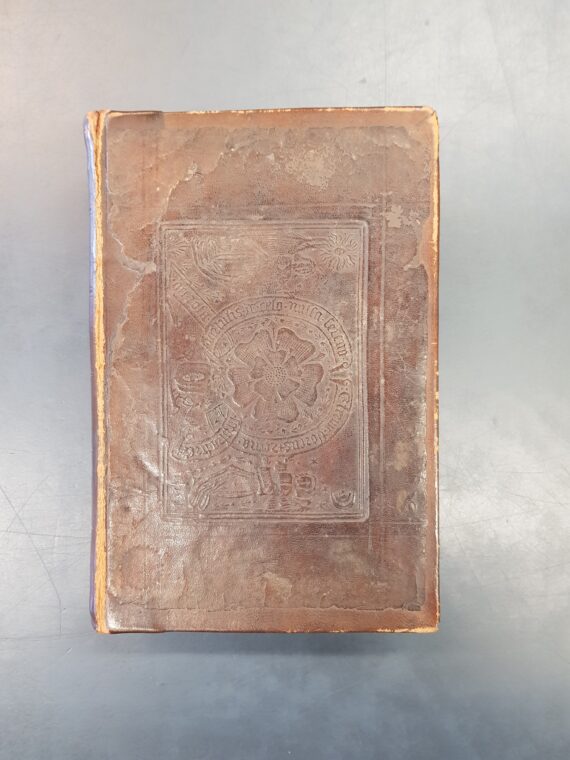

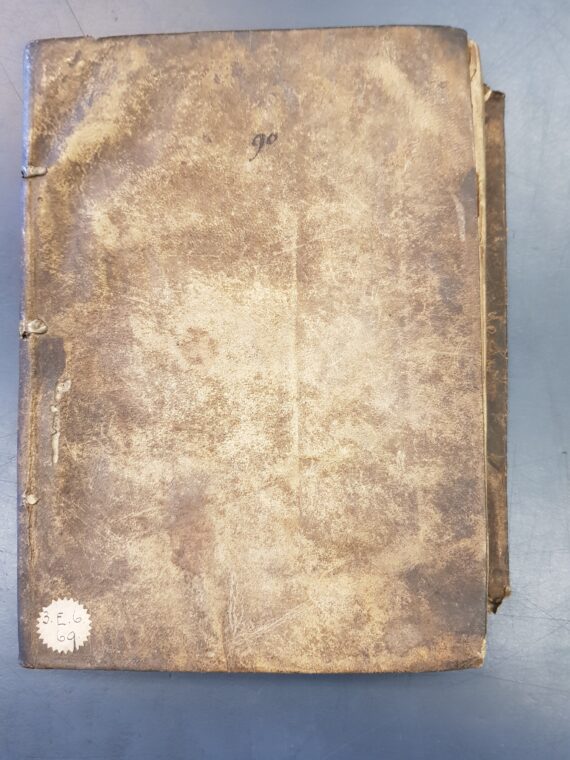

With few exceptions, they are works relating to medicine and adjacent subjects like botany, and they show both a keen interest in the literature of their profession on the part of Syddall and Hartley and their links with a wider network of readers, including other medical professionals like Thomas Cogan, an Oxford-educated physician who was the master of Manchester grammar school between 1583 and 1597. The large majority of the books, most in Latin, were printed in Europe. Since books were often initially sold unbound, their bindings also reveal something of their story: they range from high-quality decorated calf bindings to cheaper limp vellum bindings and originate from different countries on the Continent as well as England, demonstrating that even in the seventeenth century, readers in Manchester had access to scholarship and scientific literature from continental Europe.

Image 2: Blind-stamped sixteenth-century full calf binding on Champier’s Speculum Galeni (Byrom 2.I.3.69).

Image 3: Limp binding on Actuarius’ De urinis libri septem (Byrom 3.E.6.69).

Image 4: Pressed poppy in Ambroise Paré’s Opera chirurgica (Byrom 2.I.6.13).

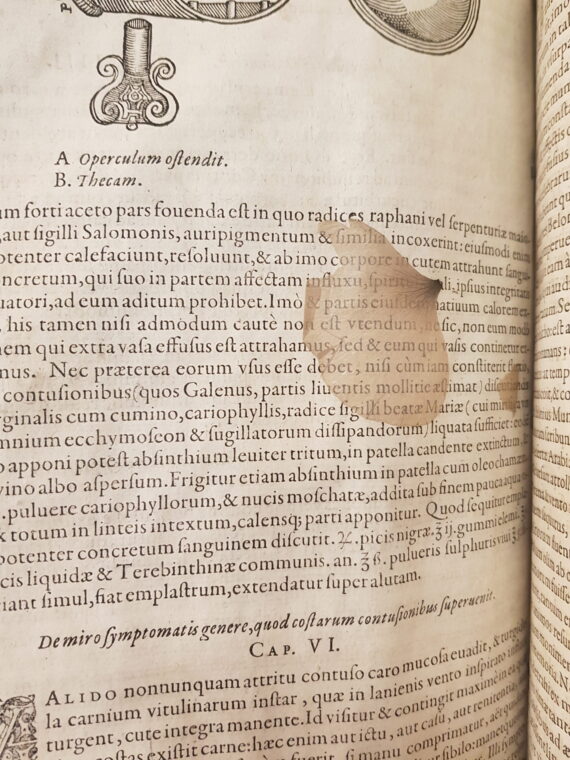

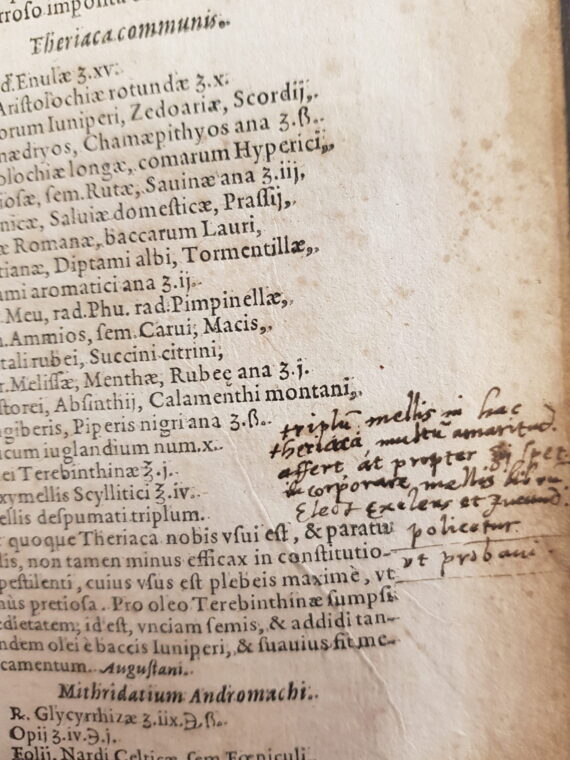

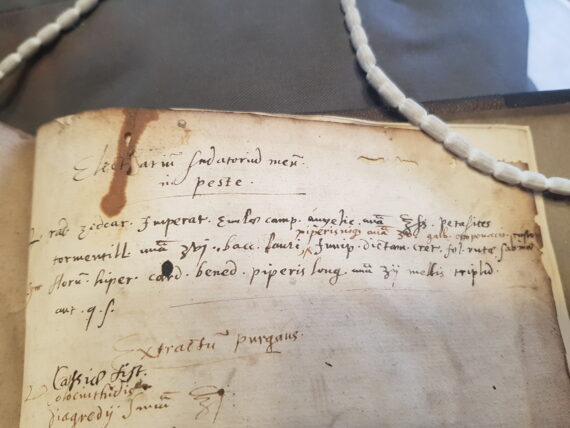

The traces Syddall and Hartley left in their books give us tantalising glimpses of their (reading) lives. Some of the books include pressed plants, possibly used in the making of remedies. One of the books has a hole burned through a page: it is easy to imagine it getting damaged in an apothecary’s workshop. Most interesting, however, are Syddall’s and Hartley’s annotations. They reveal two medical professionals at work, testing and amending medicinal recipes and occasionally creating new remedies of their own. We see Syddall, for instance, adding the words ‘ut probavi’ (‘as I have tried out’) on one occasion, and making comments like the suggestion that a remedy needs more honey to sweeten it. Syddall also added, on a blank page in one of his books, a remedy against an illness he calls ‘pestis’. This could be a general term for any kind of illness, but it could also more specifically mean the plague, of which Manchester experienced a devastating outbreak in 1605, while Syddall was active as an apothecary.

Image 5: Syddall’s annotation ‘ut probavi’ (‘as I have tried out’) in Wecker’s Antidotarium (Byrom 2.K.4.39).

Image 6: Syddall’s remedy against ‘pestis’ in Wecker’s Antidotarium (Byrom 2.K.4.39).

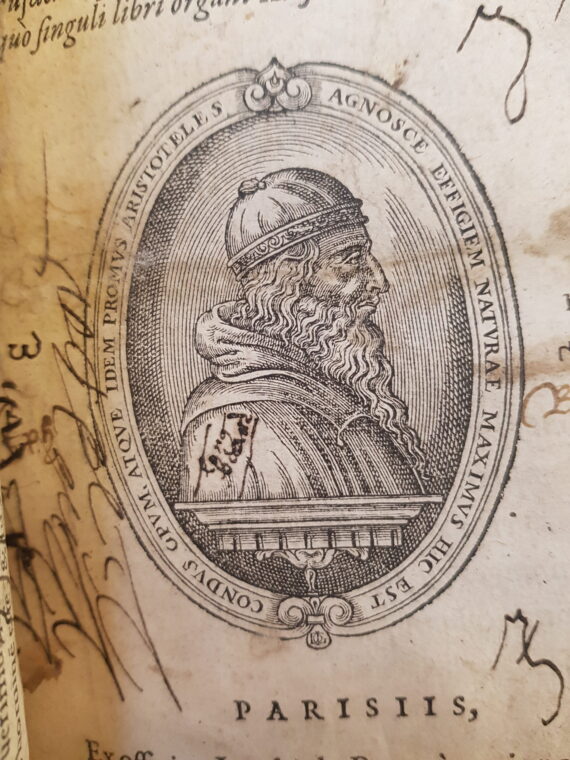

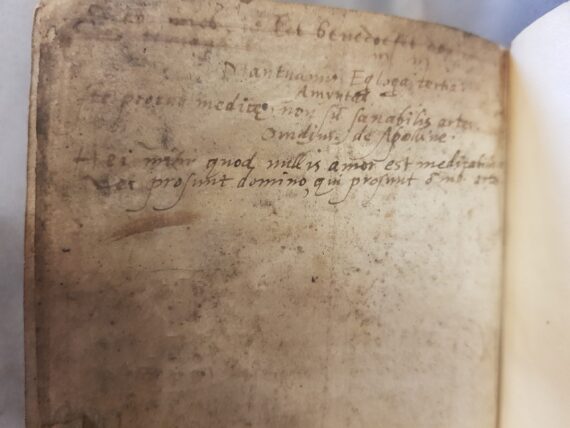

Some of the books also reveal the apothecaries’ interests beyond medicine: Syddall’s books include, for instance, an Italian grammar. Some annotations, too, are unrelated to professional matters: on an image of Aristotle on the title page of his Logic, a reader, possibly Hartley, has written the words ‘long beard’. The books also include a laundry list, in addition to quotations from poetry, ingredient lists and many other kinds of annotations: they are a fascinating look into the working and reading habits of two apothecaries who lived four centuries ago. Finally, they also reveal what Syddall saw as the limits of his art: to one of his medical works, Syddall has added a quotation from the Roman poet Ovid, which translates to ‘love can be cured by no herbs’ – even industrious readers like Syddall and Hartley, it seems, did not find cures for every ill.

Image 7: The words ‘long beard’ added by a reader to a woodcut of Aristotle in his Logic (Byrom 2.K.4.17).

Image 8: Quotations from Mantuanus and Ovid in Fuchs’ Methodus seu ratio compendiaria (Byrom 2.K.2.31).

By: Ellen Werner