- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Shakespeare’s Third Folio: Early Readers and Their Marginalia

Chetham’s Library’s copy of the 1664 Third Folio, the subject of a recent blog post, is a handsome complete copy in an eighteenth-century dark blue calfskin binding, with decorative gilt borders and gilt-edged pages. It was first mentioned in the printed catalogue of the library, published in 1826, the previous volume of which had been compiled in 1791. The Third Folio has therefore been at Chetham’s Library since the late eighteenth century or the first quarter of the nineteenth century. On the page showing the famous Droeshout portrait of Shakespeare and Ben Jonson’s poem, which refers to the portrait and praised Shakespeare’s wit (‘Reader, look/ Not on his Picture but his Book’), the name Jo: Eddowes is inscribed in a seventeenth- or eighteenth-century hand. Jo(hn?) Eddowes was probably an early or even the first owner of the book.

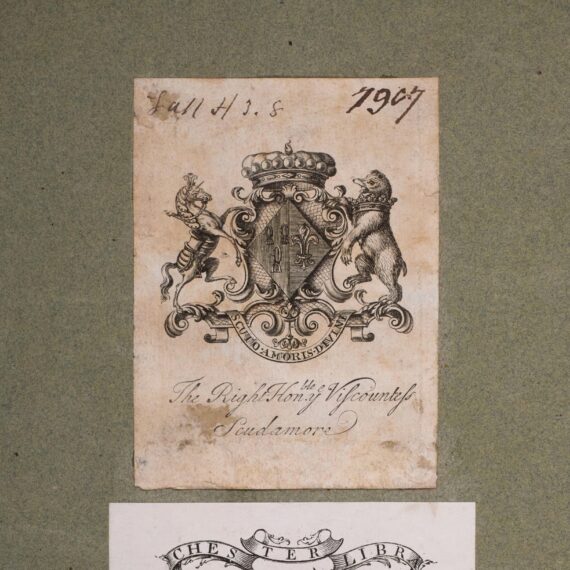

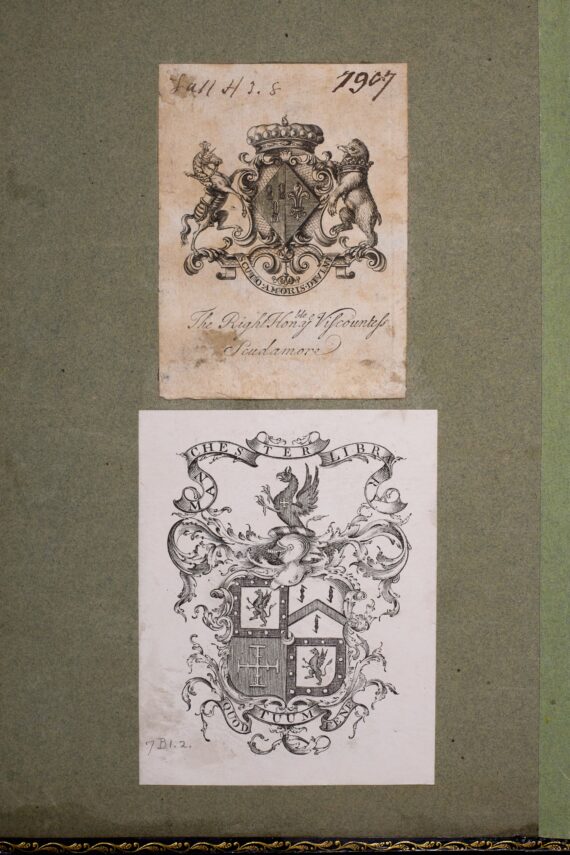

Inside the front cover, two bookplates have been pasted down. One of these is the bookplate of Chetham’s Library, showing Humphrey Chetham’s coat of arms featuring the familiar griffin. The other bookplate shows the coat of arms of the Scudamore family with the inscription ‘The Right Honble. Ye Viscountess Scudamore’. The coat of arms bears the motto ‘Scuto Amoris Divini’ (‘by the shield of divine love’), and the deviser of the motto chose Latin phonological approximations to the English sounds, with ‘scut-’ signifying ‘shield’ in Latin and ‘amor-’ signifying ‘love’. The English etymology of Scudamore (probably a village place name meaning ‘low moor’) was therefore disregarded in order to produce a new, more elevated Latin-inspired meaning.

Figure 1: The bookplates of Viscountess Scudamore and Chetham’s Library in the Third Folio (Chetham’s Library, Mun. 7.B.1.2, front pastedown).

The Third Folio is the sole book in Chetham’s Library whose previous owner can be identified as Viscountess Scudamore. Frances Scudamore (1684-1729) was the daughter of Simon, fourth Baron Digby, and the wife of the third Viscount Scudamore of Sligo, the Tory MP for Herefordshire. He predeceased her, dying in 1716 at the age of 32 from the effects of a fall from his horse. During the early 1700s, the Third Folio is likely to have been kept in the library of the Herefordshire mansion of the Scudamores, Holme Lacey, which is now a hotel.

In 1623, the First Folio was priced at 15 shillings without a binding, or about £1 with a binding. The price of the Third Folio in 1664 would have been perhaps a few shillings more. There is no record of the volume being donated to Chetham’s Library, so it is likely that it was purchased at some point between 1792 and 1826. On one of the blank initial leaves there is a pencilled price of £65, which may have been the price that was paid for it by the library. Meanwhile, inside the back cover, a small newspaper cutting referring to a Sotheby’s sale in March 1899 of another copy of the Third Folio for £260 has been pasted down. At the 2025 Melbourne book fair, a copy of the Third Folio was on sale for $2 million.

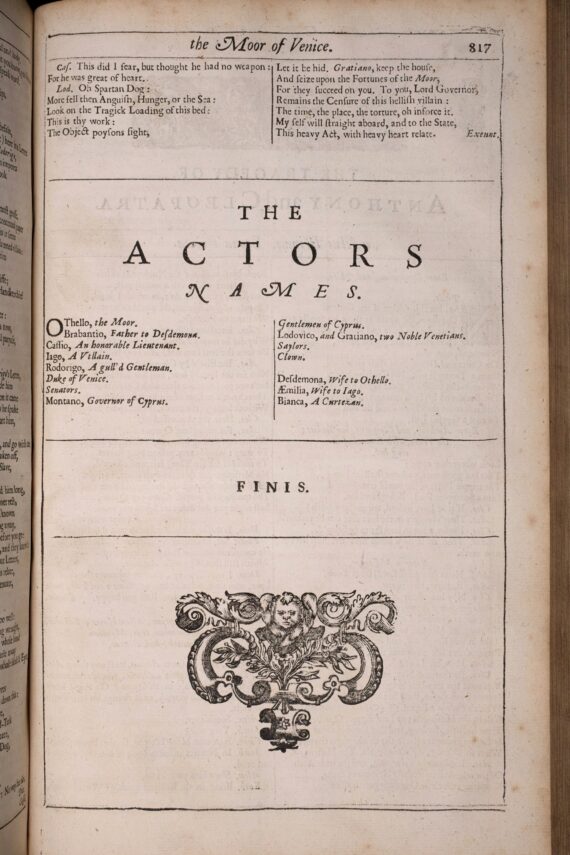

Figure 2: The character list for Othello in the Third Folio (Chetham’s Library, Mun. 7.B.1.2, p. 817).

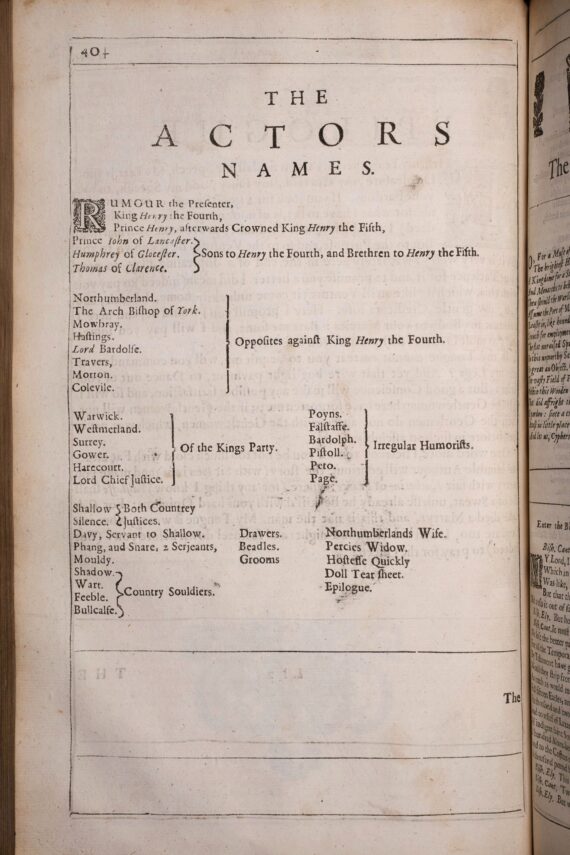

Chetham’s Library’s copy of the Third Folio bears some marks of past readers studying the texts closely. In the early modern period, the convention of printing a list of characters and the location of the action before the start of a play was starting to become standard. In the Third Folio, as in the previous two editions, the character lists are highly inconsistent. Only seven plays feature ‘The Actors Names’ (i.e. the names of the characters) but, unusually, these are printed at the end of each play. In most cases, the list of characters fills a space on the final page of the play text that would otherwise be blank. For Henry IV Part 2 and Timon of Athens, however, the lists occupy a whole page, and the characters are grouped not only according to their status and gender, but also their dramatic functions or allegiances.

Figure 3: The character list for Henry IV Part 2 in the Third Folio (Chetham’s Library, Mun. 7.B.1.2, p. 404).

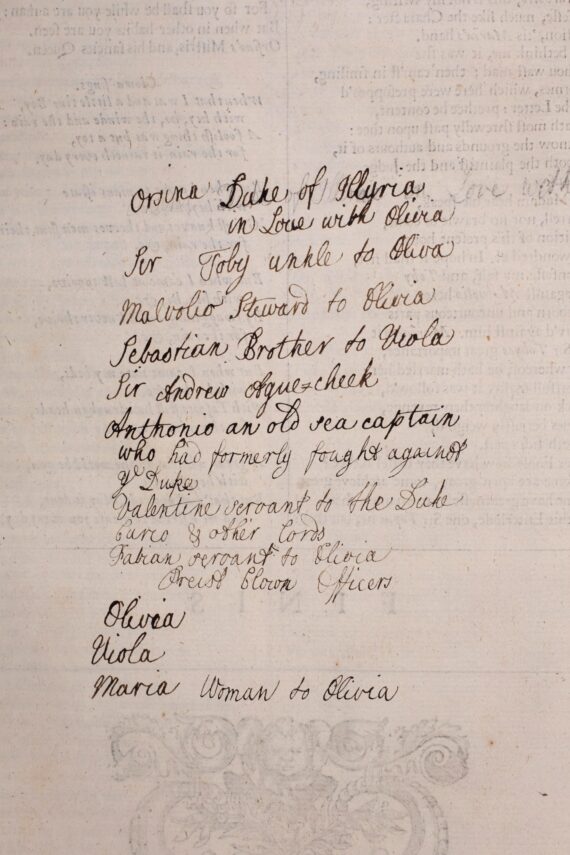

In Chetham’s Library’s copy of the Third Folio, an early reader added character lists at the conclusion of five comedies: Twelfth Night; The Taming of the Shrew; As You Like It; The Merchant of Venice, and The Comedy of Errors. These lists follow the practice of some printed lists in identifying some characters’ occupations, status and relationships to other characters, and are presented approximately in the order of the social status or importance of the character’s role in the play. The female characters are listed separately after the male characters. In the list compiled by a reader of the Twelfth Night, Orsino appears at the head of the list, identified as the Duke of Illyria ‘in love with Olivia’. Sir Toby Belch appears second in the list, although his surname is omitted and he is identified as the ‘uncle to Olivia’. Oddly, the reader has given the most detailed description to a relatively minor character: ‘Anthonio, an old sea captain who had formerly fought against ye Duke’.

Figure 4: An early reader’s character list for Twelfth Night in the Third Folio (Chetham’s Library, Mun. 7.B.1.2, p. 276).

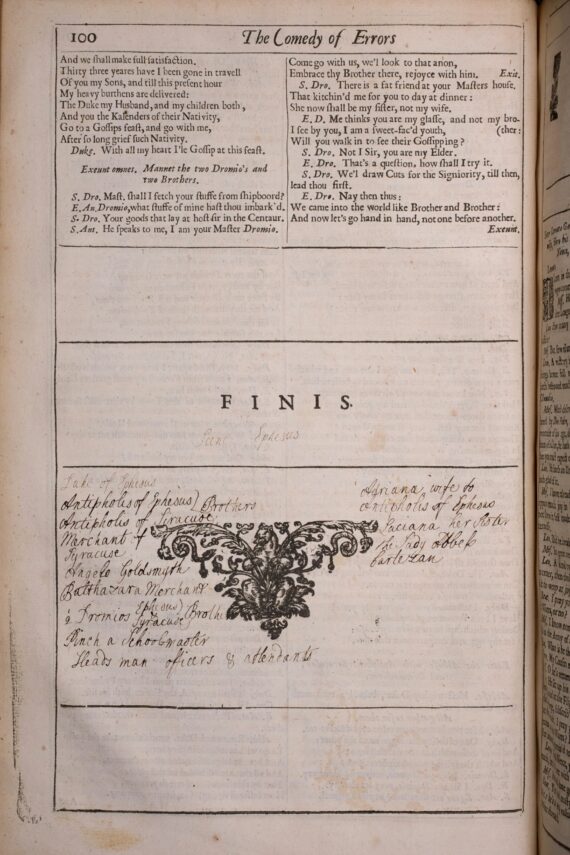

In the case of The Comedy of Errors, the compiler may have felt that a character list would help them follow the complexities of the plot. This play’s comedic confusion arises from there being two sets of identical twins, accidentally separated at birth; each twin has the same name as his brother, with one set of twins being masters and the other set their servants. The plot is based on a comedy by the Roman playwright Plautus, in which the plot similarly revolves around multiple mistaken identities. Unless a reader had a strong theatrical imagination, private reading of the text was likely to produce even more confusion than a public performance. The act of compiling and consulting the list may have helped the early reader of the play clarify the characters and the plot.

Figure 5: An early reader’s character list for The Comedy of Errors in the Third Folio (Chetham’s Library, Mun. 7.B.1.2, p. 100).

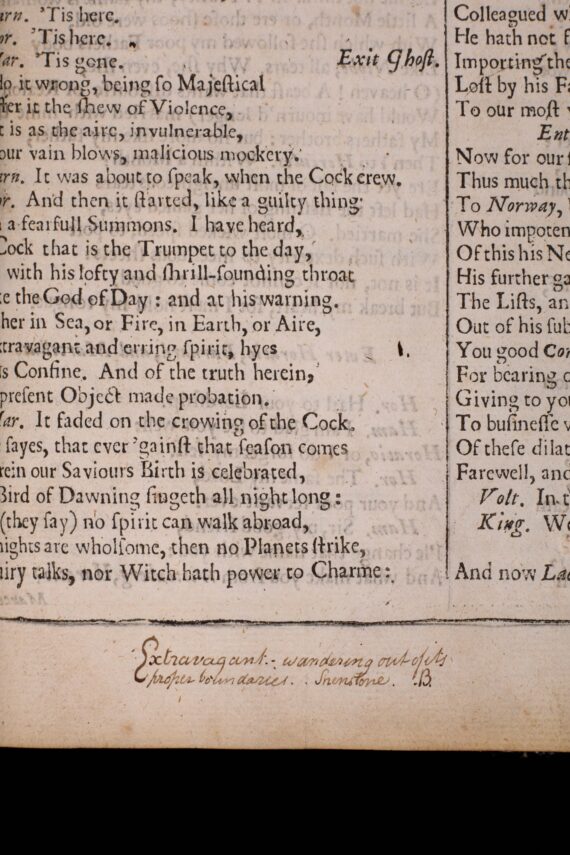

The printed text of Hamlet carries two marginal notes. The first is a gloss of Horatio’s description of the Ghost of Hamlet’s Father in Act 1 scene 1 as an ‘extravagant and erring spirit’. The Ghost describes how he is punished in Purgatory in daytime but leaves each night to wander the earth, and the gloss reads: ‘extravagant: wandering out of its proper boundaries’. The wording of the reader’s definition is very close to that of the first meaning given by Dr Samuel Johnson in his Dictionary of the English Language (1755): ‘wandering out of his bounds’. According to Johnson, this was ‘the primogeneal sense [of the term], but not now in use’. This archaic meaning was derived from the word’s Latin etymology: ‘extra’ means ‘outside of’, and ‘vagrans’ means ‘wandering’. By the mid-eighteenth century, this meaning of ‘extravagant’ had been largely displaced by a semantic shift towards associations with wildness and recklessness, often financial. Remarkably, the usage that Johnson quoted to support his definition was the same line from Hamlet that was glossed by this reader.

Figure 6: A reader’s definition of the use of ‘extravagant’ in Hamlet (Chetham’s Library, Mun. 7.B.1.2, p. 731).

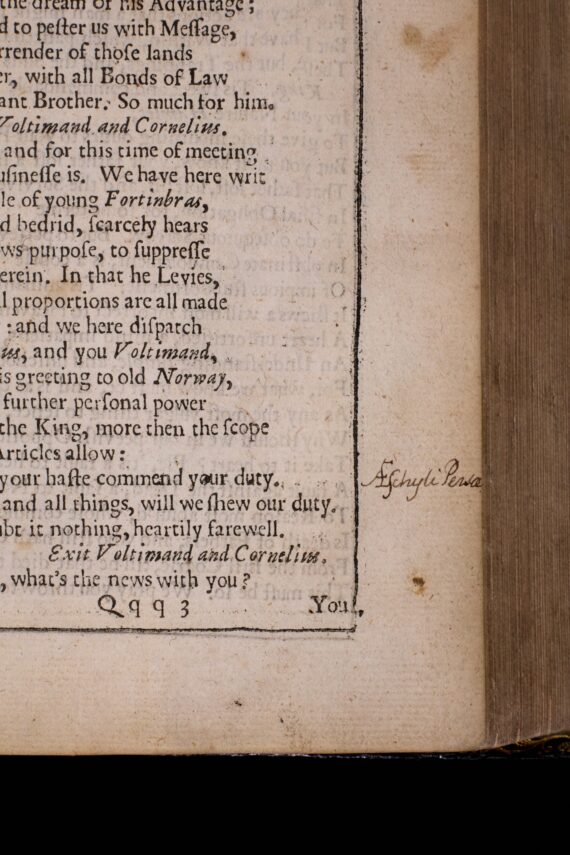

One other annotation occurs in the text of Hamlet. Next to Claudius’s speech in Act 1 Scene ii, in which he sends his messengers Cornelius and Voltemand on a mission to the king of Norway, a reader has written in Latin the marginal note ‘Aeschyli Persae’, a reference to what is probably the earliest extant Greek tragedy, Aeschylus’ Persians. It is difficult to see any direct and specific relevance of Claudius’s speech to Aeschylus’s play, and it is more likely that the reader had a comparison of characters and dramatic situations in mind. In both Persians and Hamlet, the ghost of a deceased father returns from the underworld and comments on his son’s behaviour. In Persians, the ghost of Darius is appalled by what he learns of Xerxes’s military failure, and attributes it to insanity: ‘what else but a disease of mind was this | that took hold of my son?’ Meanwhile, the revelations of the Ghost of Hamlet’s Father initially inspire Hamlet to feign madness in order to achieve his revenge. Later critical comparison of Shakespeare with Aeschylus has centred not on Persians but on the Oresteia, and the similarity of Hamlet and Orestes as sons seeking revenge for the deaths of their fathers. The early reader of this copy of Hamlet was intrigued not by the more obvious parallel with the Oresteia’s theme of revenge, but by that between the return from the afterlife of the two paternal ghosts.

Figure 7: A reader sees a parallel between Hamlet and Aeschylus’ Persians (Chetham’s Library, Mun. 7.B.1.2, p. 731).

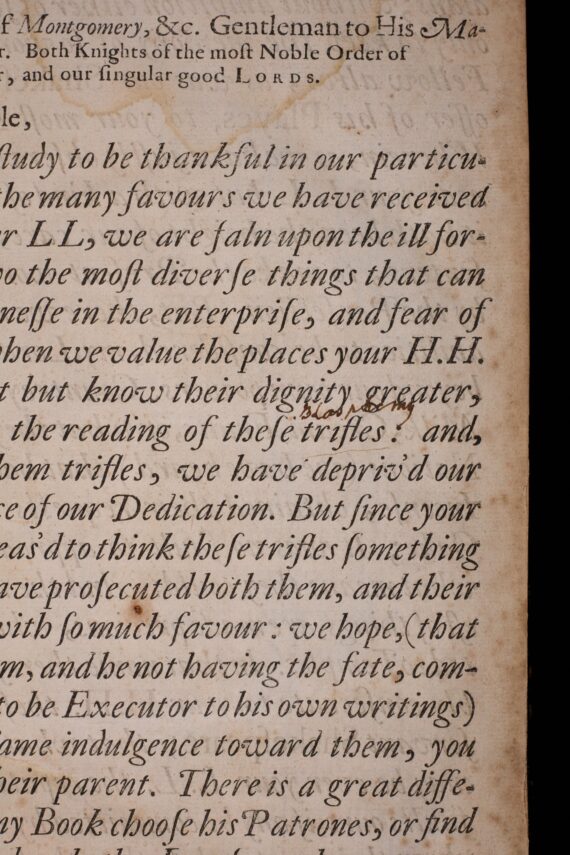

Finally, one other, probably later, handwritten addition to Chetham’s Third Folio is less learnedly obscure but very strongly felt. The book’s dedicatory epistle to William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke and Philip Herbert, Earl of Montgomery, is couched in the typical language of seventeenth-century flattery of aristocratic patrons, but Heminge and Condell went further in their sycophancy and appear to disparage the plays that they are supposedly recommending. They present the plays to the earls as ‘the remains of your servant Shakespeare’, request their ‘indulgence’, and refer to the plays as ‘these trifles’. Above the word ‘trifles’, a reader has written a single word, ‘blasphemy’. The judgement is a noteworthy example of literal Bardolatory, with Shakespeare’s plays conceived of by the reader as if they were a sacred text.

Figure 8: A reader expresses their shock at the apparent disparagement of Shakespeare’s plays (Chetham’s Library, Mun. 7.B.1.2, n.p.).

The word ‘Bardolatory’ was coined by G. B. Shaw in 1901 to denote the excessive worship of Shakespeare that developed from the time of Garrick’s Shakespeare Jubilee in 1769 and peaked in Victorian England with such panegyrics as Thomas Carlyle’s in On Heroes and Hero-Worship (1841). To express the supreme value that he placed on Shakespeare, Carlyle proposed a hypothetical choice between losing Shakespeare or the ‘Indian Empire’. Despite his well-deserved reputation as a racist imperialist, Carlyle opted to lose the Empire on the grounds that it was only temporary, while Shakespeare would undoubtedly act as a nationally unifying force a thousand years in the future. As a Victorian Bardolator, Carlyle was highly influential. The hand in which the word ‘blasphemy’ is written appears to be different from and later than that of other additions to the text, and the addition may well have been made by a nineteenth-century reader who shared Carlyle’s view of Shakespeare. If this was the case, then it would have occurred after the book was acquired by Chetham’s Library. Such was the reader’s sense of outrage at the plays being labelled ‘trifles’ that they were willing to flout the library’s rules in order to express their extreme indignation at the apparent belittlement of Shakespeare’s work.

Blog post by John Cleary

With thanks to Laura Bryer, Emma Nelson and Ellen Werner for their help and advice.