- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Shakespeare’s Third Folio: The Page vs. the Stage

One of the most fascinating books in Chetham’s Library’s less well-known literature collection is a copy of Mr William Shakespeare’s comedies, histories and tragedies, published according to the true original copies, better known as the Third Folio (1664). The title page of this work specified that it was ‘the third impression’, meaning that it largely reproduced the First and Second Folios, published respectively in 1623 and 1632. The First Folio is a collection of thirty-six plays, only eighteen of which had been previously published in the small individual editions known as quartos. Without it, we would not have half of Shakespeare’s dramatic output, including Macbeth, Julius Caesar, The Tempest and Twelfth Night. Although it has never enjoyed the celebrity status of the First Folio, the Third Folio has two major claims to distinction: its comparative rarity, and the addition of a group of plays not published in the First and Second Folios. Out of the seven extra plays included at the end of the Third Folio, only one—Pericles, Prince of Tyre (1607)—is now generally acknowledged to be mainly the work of Shakespeare. All seven of the additional plays had been published during Shakespeare’s lifetime in quarto form, and on the title pages of these editions they had been attributed either to ‘William Shakespeare’ or ‘W.S.’, an indication of the commercial power of Shakespeare’s name even during his own lifetime.

The inclusion of Pericles in the Shakespearean canon facilitates a fuller picture of Shakespeare’s obsessions during the later part of his writing career. The play deals with themes of restitution and the re-establishment of justice, linking it to the other late plays such as The Winter’s Tale, Cymbeline and The Tempest, which are often classified as romances rather than comedies or tragedies. Pericles, like Leontes in The Winter’s Tale, after years of suffering and separation, regains his daughter and his wife. Pericles is an exiled ruler who, with supernatural aid, is ultimately restored to his land, as is Prospero in The Tempest. The heroines of the four plays—Marina, Perdita, Imogen and Miranda—all embody fortitude and innocence. All four romances have potentially tragic elements, too, but the sense of injustice and loss is resolved in denouements featuring recognitions, restorations, healing and harmony.

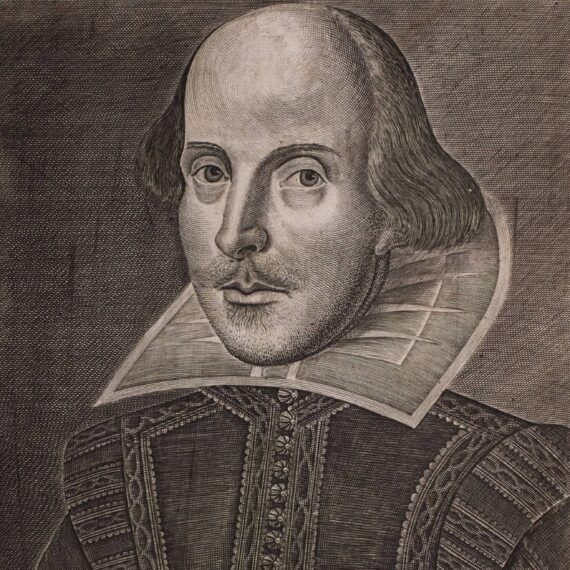

Figure 1: The Droeshout Portrait in the First Folio.

The Third Folio is a rarer book than the First Folio. Some copies of the Third Folio bear the date 1663 while others, including Chetham’s Library’s copy, are dated 1664. It is likely that 750 copies of the First Folio book were printed, of which at least 235 survive, while only about 182 copies of the Third Folio have thus far been traced. Since the seventeenth-century London book trade was centred in the area around St Paul’s Cathedral, unsold copies of the Third Folio are thought to have been destroyed two years after its publication during the Great Fire of London in 1666.

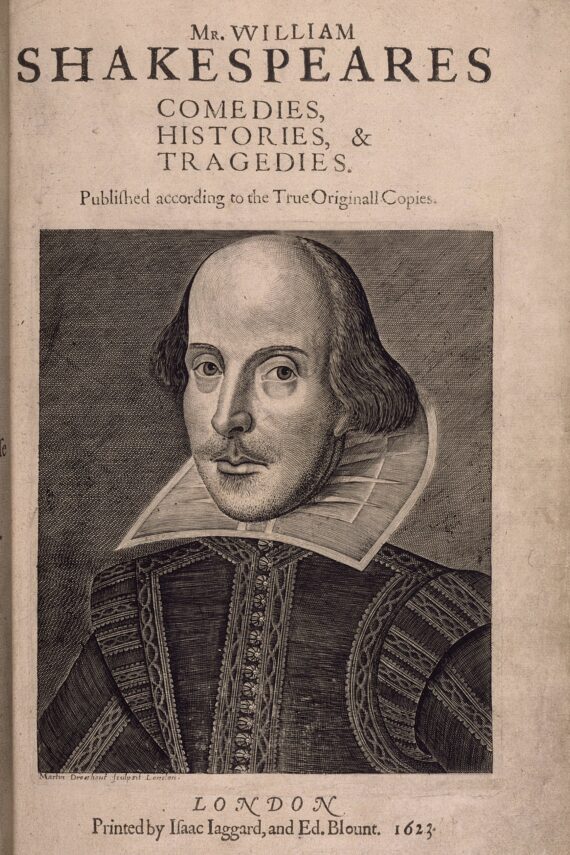

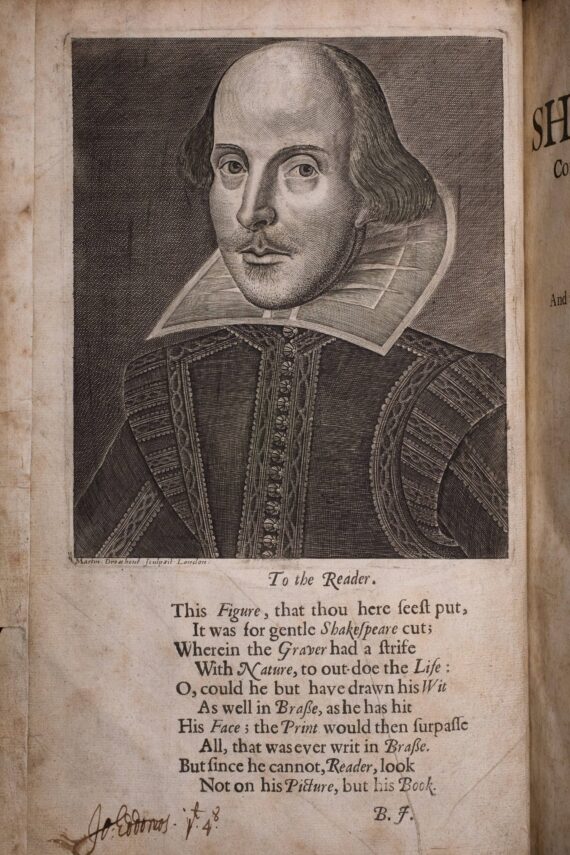

The layout of the first two printed pages of Chetham’s Library’s copy of the 1664 Third Folio differs from that of all earlier printings. In this copy, the famous Droeshout engraved portrait of Shakespeare and Ben Jonson’s poem ‘To the reader’ appear on the first printed page, facing the title page. In the First, Second and 1663 Third Folios, the first printed page contains only Jonson’s poem, while the engraved portrait occupies most of the title page. The printers of the 1664 Third Folio moved the Shakespeare portrait to the preceding page in order to make room for a list of the seven extra plays on the title page. In the 1663 Third Folio, this list of plays appears near the back of the volume, before the seven supplementary plays. The greater prominence afforded to the list in the 1664 printing may indicate their value as a unique selling point of the Third Folio. Indeed, when the Bodleian Library acquired a Third Folio upon its publication, it de-accessioned its copy of the First Folio on the grounds that it was obsolete, only re-accessioning the same copy two-hundred-and-fifty years later.

Figure 2: The Droeshout Portrait and Ben Jonson’s ‘To the reader’, facing the title page, which lists the seven additional plays in the 1664 Third Folio (Chetham’s Library, Mun. 7.B.1.2, facing title page).

Paratextual material from the First Folio was also carried over into the Third Folio. As well as Jonson’s poem, the Third Folio contains two letters signed by Shakespeare’s fellow actors in the King’s Company, John Heminge and Henry Condell, who are usually credited with ‘editing’ the First Folio. They presumably collected and provided the printers with the texts of the thirty-six plays, including the eighteen previously unpublished plays, but did not ‘edit’ in the modern sense of ensuring presentational consistency. The Third Folio was ‘printed for P.C.’, Philip Chetwinde, who probably added the seven extra plays ‘never before printed in folio’, as the title page boasts.

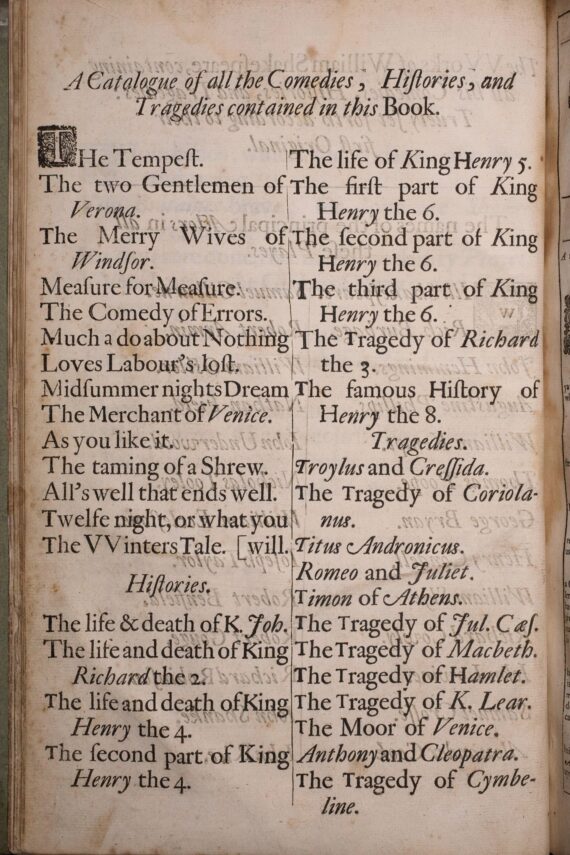

The first letter in all of the Folios is a dedication to the aristocratic brothers, William and Philip Herbert, using the sycophantic language that was standard for addressing patrons at the time. The second letter, ‘To the great variety of readers’, encouraged the reader to buy the book. These are followed by four dedicatory poems in praise of Shakespeare, a list of actors, and a catalogue of the plays divided into the familiar genres of comedies, histories and tragedies. Although the text of Troilus and Cressida was included in the First Folio, the title of the play was not listed; in the Third Folio, the omission was rectified, and ‘Troylus and Cressida’ appears at the head of the list of tragedies.

Figure 3: The Comedies, Histories and Tragedies listed in the order in which they appear in the Third Folio (Chetham’s Library, Mun. 7.B.1.2, n.p.).

The publication of the Third Folio in 1663–4 reflects the renewed interest in drama during the Restoration period. Performances of plays had been illegal between 1642 and 1660, and the Restoration of Charles II brought with it an enormous appetite for the many types of entertainment that had been denied the mass of people during the period of the Cromwellian Republic. There were initially few new plays to mount, so theatrical producers such as Thomas Betterton, Thomas Killigrew and William D’Avenant turned to texts from earlier in the century, chief among them Shakespeare’s plays. By the 1660s, however, these plays had come to seem very old-fashioned and did not always delight the public. Samuel Pepys, an ardent theatre-goer, recorded enduring the very first Restoration performance of Romeo and Juliet in March 1662: ‘the play of itself the worst I ever heard in my life, and the worst acted that I ever saw these people do’. Six months later, he was no happier with A Midsummer Night’s Dream, denouncing it as ‘the most insipid ridiculous play that I ever saw in my life’. Despite Jonson’s praise in his second dedicatory poem (‘he was not of an age but for all time!’), the image of Shakespeare as a timeless genius was not yet firmly established.

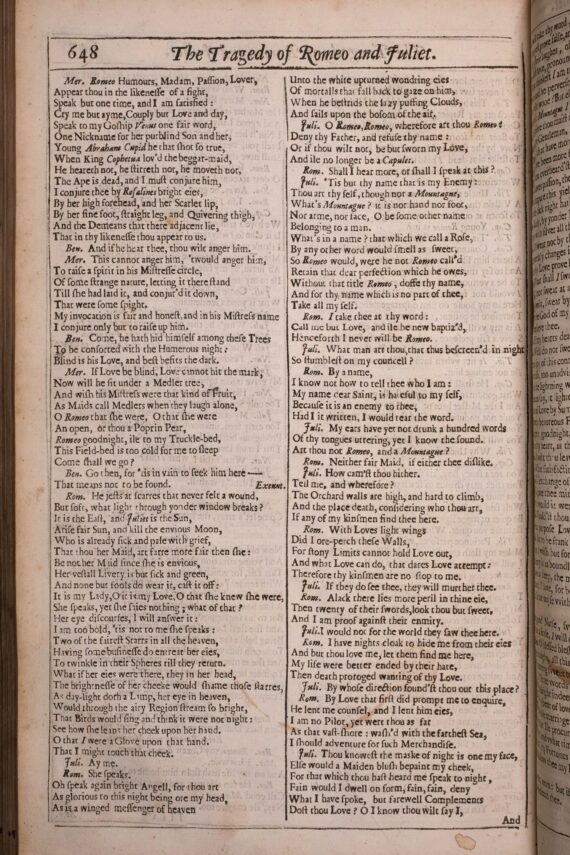

Figure 4: The balcony scene in Romeo and Juliet that failed to entrance Samuel Pepys (Chetham’s Library, Mun. 7.B.1.2, p. 648).

Restoration producers of plays quickly realised that if Shakespeare’s plays were to be staged, they must be adapted to suit the taste of the times. Accordingly, extended musical interludes, singing, dancing and extravagant visual spectacle featured prominently, in a marked contrast to the more austere and technically limited stagings of the Elizabethan and Jacobean theatres. A further radical change saw female roles played by actresses rather than boy actors for the first time, and such was the popularity of women on the stage that adaptations of older plays increased the number of female parts. In William D’Avenant’s and John Dryden’s adaptation of The Tempest, for example, both Caliban and Miranda are given sisters, Sycorax and Dorinda, with entirely new romantic entanglements. Another cultural shift was evident in the Restoration distaste for unrelieved tragedy. Some previously tragic dramas were given happy endings. In Nahum Tate’s notorious re-write of King Lear, the aged monarch lives on at the end of the play in serene retirement, and instead of being hanged, Cordelia becomes queen and finds true love and happiness with Edgar. Chetham’s Library’s copy of the Third Folio contains a book plate indicating that it was owned by the Viscountess Scudamore in the early eighteenth century. If the lady attended a performance of King Lear and then rushed home to read the text of the play in her copy of the Third Folio, she would have had a very unpleasant surprise!

It is clear that there was a disconnect between the versions of Shakespeare being seen by audiences on the late seventeenth-century stage, and the plays as they were published in the 1663 and 1664 Third Folios, as well as the subsequent edition, the Fourth Folio of 1685. In contrast to the free theatrical adaptations, the Third Folio retains Heminge and Condell’s insistence from the First Folio that the texts were ‘published according to the true original copies’. They refer to the earlier quarto versions of the plays, which were ‘stolne, and surreptitious copies, maimed, and deformed by the frauds and stealthes of injurious impostors’. These are now ‘offer’d to your view cur’d, and perfect of their limbes; and all the rest, absolute in their numbers as he [Shakespeare] conceived them’. Heminge and Condell’s boast of the integrity and authenticity of the texts that they published had become highly ironic by the late seventeenth century, since the texts were no longer seen as theatrically viable in their original form. The Third Folio, even more than the First and Second Folios, was a collection of texts not for theatrical performance, but for private reading and study.

Blog post by John Cleary