- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

‘Strange Knowledge of a Crow’: A Yeoman Farmer Annotates Holinshed’s Chronicle

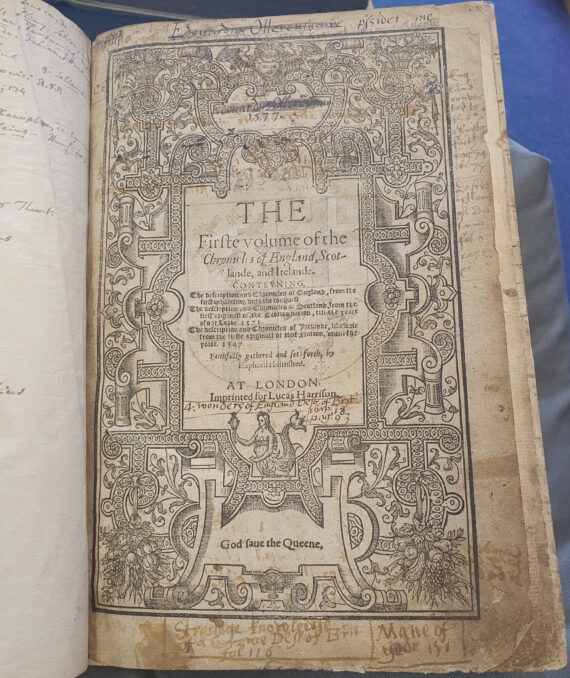

One of the most striking annotated books in the collection of Chetham’s Library is a copy of Raphael Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland, annotated by a yeoman farmer from the North of England (Radcliffe Collection 2.H.2.15). Better known simply as Holinshed’s Chronicles, the volume is an extensive account of the history and topography of the British isles and published in 1577, with a revised edition following ten years later.

Although they later came to be most closely associated with the name of its chief contributor, Raphael Holinshed, the Chronicles were a multi-author venture, both relying on many ancient and medieval source texts and including contributions from a number of prominent sixteenth-century scholars. The work is in two volumes, which in turn consist of different sections focussing on individual countries and their geography and history. The work, detailed and wide-ranging even as it currently stands, started out as a ‘cosmography’, a description and history of the world. Although the scope of the project diminished during the lengthy writing and publication process, it retains elements of its original ambition: the Chronicles are more than historiography and include lengthy descriptions of the topography of the countries discussed, as well as reprinting some source texts at full length. This wealth of mixed-genre materials was part of the attraction the Chronicles held for their readers – the best-known of whom, William Shakespeare, drew on the Chronicles to write his history plays.

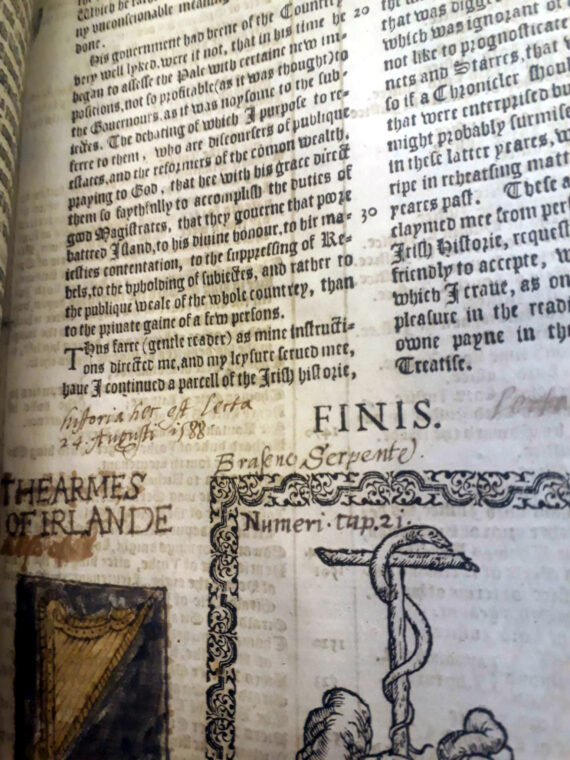

Another reader who was fascinated by the Chronicles and the wealth of historical and topographical information they provided was Edward Ollerenshawe, a yeoman farmer from Chapel-en-le-Frith in the Peak District. Hailing from a prominent local family, Ollerenshawe signed his copy on the title page and stated on the final page that he had read the book in 1588.

Title page with Ollerenshawe’s signature.

Final page with inscription by Ollerenshawe: ‘historia hec est lecta 1588’ (‘This history was read in 1588′).

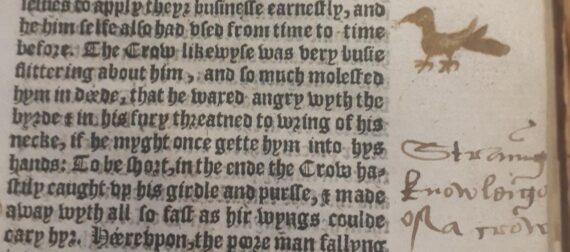

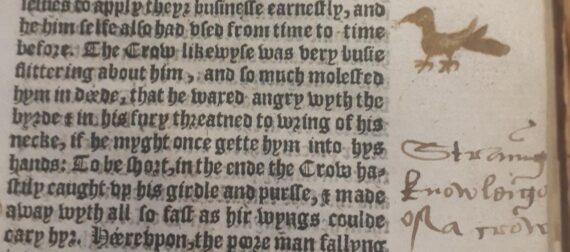

Ollerenshawe’s annotations in the Chronicles display a keen interest in a number of topics, ranging from agriculture to history and from myths to linguistics. In addition to comments on all of these subjects, his book features doodles of animals, places or objects mentioned in the printed text, such as his drawing of a bow and arrow next to a passage about Robin Hood and Little John. By illustrating his copy in this way, Ollerenshawe created a visually striking means of marking passages to which he wanted to return. Frequently, such doodles accompany references to magical or legendary items and stories, such as a drawing of a harp illustrating the tale of a harp hanging on the wall playing of its own accord. Another such illustration is Ollerenshawe’s rather charming rendering of a crow, illustrating the tale of a crow saving a miner by stealing his purse and thus luring him away from a mine that was to collapse shortly thereafter, an occurrence on which Ollerenshawe comments: ‘Strange knowledge of a crow.’ Miraculous stories such as this seem to have exercised a particular fascination for Ollerenshawe and led him to mark them with his illustrations.

Illustration of the crow.

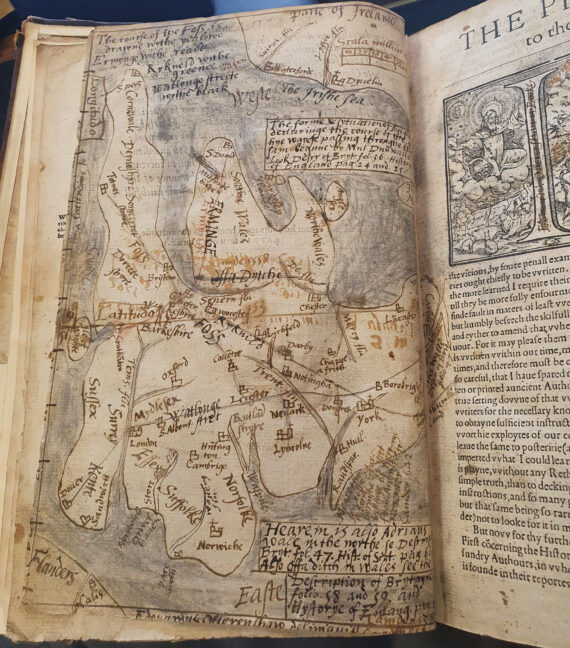

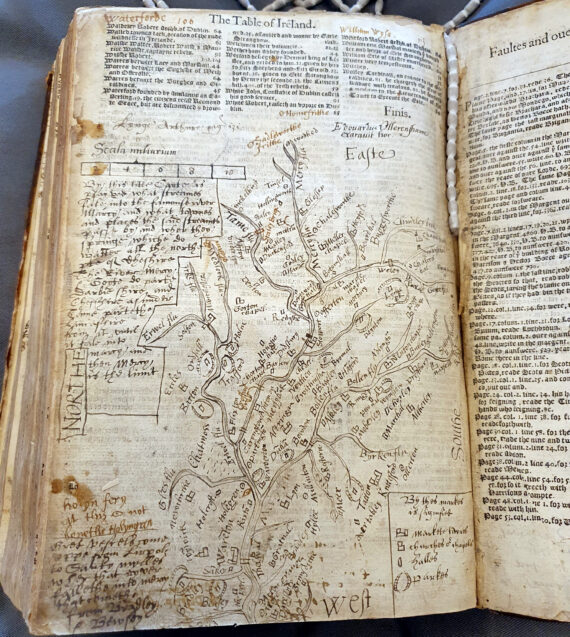

This interest in visual representation of the text’s contents also informed Ollerenshawe’s most arresting additions to the Chronicles: his book features hand-drawn maps of Scotland and England, as well as a more detailed map of the area around his own home in the Peak District. His maps represent an interest in the areas that provided the setting for the history in Holinshed’s Chronicles, but they also demonstrate Ollerenshawe’s fascination with local history and a desire to see his native region represented within the picture of Britain drawn by Holinshed. His map of England, for instance, features Chapel-en-le-Frith rather prominently – arguably lass an accurate representation of the geography of England than a visualisation of Ollerenshawe’s own mental map of the country, where his hometown would naturally have taken centre-stage. His map of the North West, too, features information that would have been of practical use to Ollerenshawe, such as local market towns. In addition, he carefully includes the most important estates, halls and parks in the area, many of which still stand today, such as Lyme Park, Dunham Massey and Tatton Park.

Image of the map of England.

Image of local map.

Ollerenshawe’s preoccupation with local history and topography also led him to be particularly thorough in his annotations of those passages in the Chronicles that give accounts of regions Ollerenshawe knew well, chiefly in North West England. On a page listing market days and fairs all over England, for instance, Ollerenshawe has added a date for the fair in ‘Garstan in Lanksh’ (Garstang in Lancashire) and crossed out the market date of 17 July in Chapel-en-le-Frith. He also supplies units of measurement that were in use locally and provides corrections where he disagrees with the Chronicles’ spelling of North English place names, adding his local knowledge to the bigger picture of the Chronicles.

This Chetham’s Library copy of Holinshed’s Chronicles shows a reader’s intense engagement with a book. Edward Ollerenshawe not only read his Chronicles, but annotated and illustrated them, demonstrating his interest both in the information the book provided about the history and geography of Britain and his passion for – and detailed knowledge of – the characteristics of his native region. His annotated Holinshed is a representation of his interests and requirements as a reader, combining an interest in practical matters like agriculture with a fascination for the strange and supernatural and an interest in national and international concerns with a love for the local and with practically useful place-specific information: Ollerenshawe’s annotations are the product of a rich and complex reading life lived in North West England.

By Ellen Werner

6 Comments

Jane Sellek

It is interesting that alongside the story of a crow saving a miner, underneath the bird Ollerenshawe has drawn in the margin he has actually written Strange knowledge of a rook, i.e. not a crow.

ferguswilde

Thanks Jane, we’re pretty confident that says ‘crow’ – the letter forms are different from modern ones.

Andrew Mitchell

Thanks very much for a very interesting article

ferguswilde

Thanks, Andrew, glad you found it interesting. Ellen is finding many interesting corners in the collections!

Barbara Gent

As always something fascinating to delight the reader. Thank you and may I wish you all a very happy and peaceful 2024.

Barbara

ferguswilde

Thanks, Barbara! Glad you enjoyed it, and Happy New Year to you!