- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Sweated industries: “almost ceaseless toil, hard and unlovely to the last degree”

‘… earnings barely sufficient to sustain an existence; hours of labour such as to make the lives of the workers periods of almost ceaseless toil hard and unlovely to the last degree; sanitary conditions injurious to the health of the persons employed and dangerous to the public.’

House of Lords Select Committee definition of ‘sweated’ labour, 1890

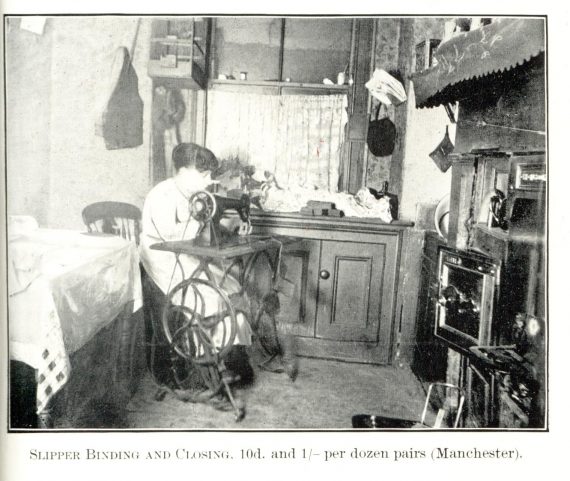

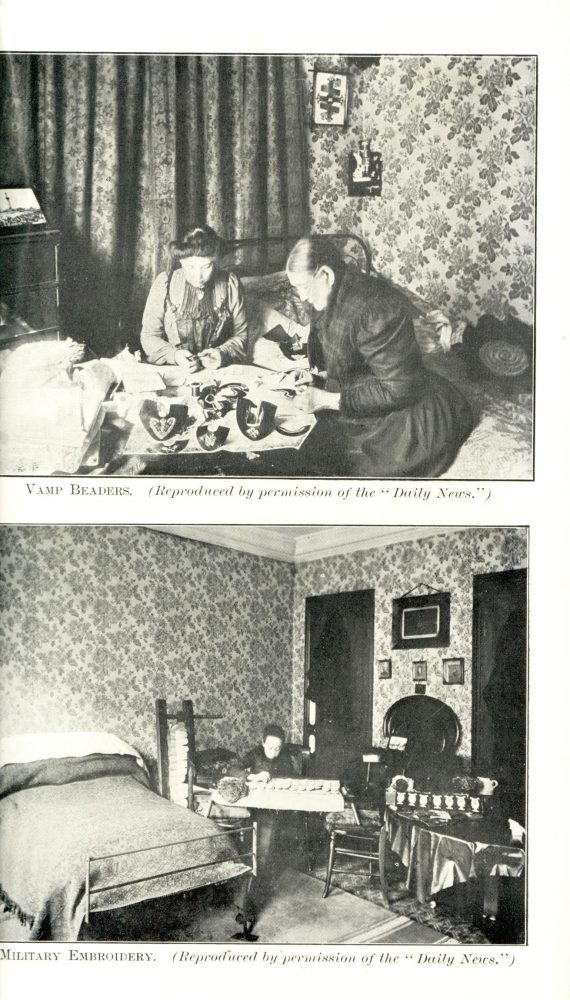

At the beginning of the twentieth century the survival of poor families often depended on women working. Unfortunately most of the work open to them was low-paid “sweated labour”: working long hours in dreadful conditions for very low pay, either in factories or earning a pittance at home in repetitive work. The occupations included making umbrella tassels, beaded bows for ladies shoes, matchboxes, paper bags or mouse traps; military beading, button hole sewing, shirt finishing, folding bible pages, beading shoes (‘vamps’), hemming pocket handkerchiefs and carding buttons. Production workers were hugely exploited, as manufacturers aimed to produce goods as cheaply as possible to meet consumer demand.

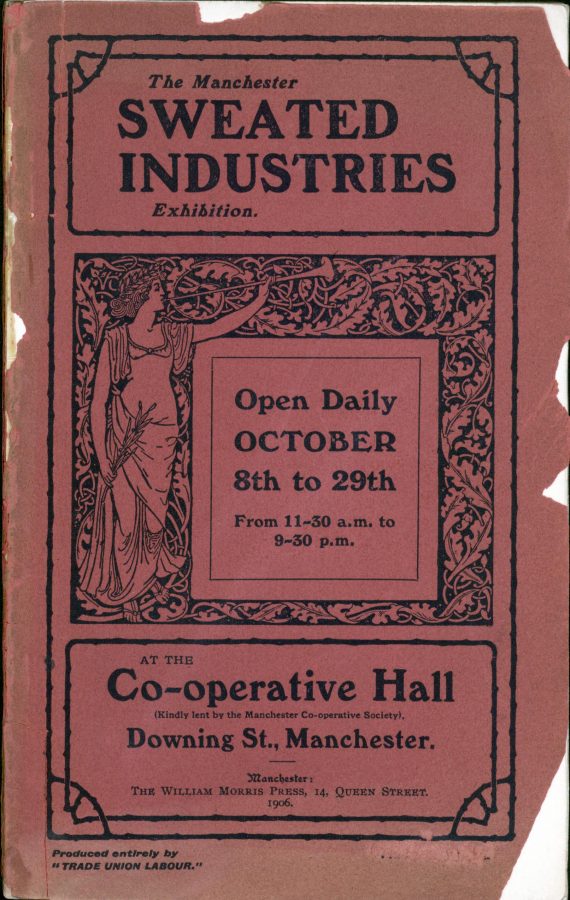

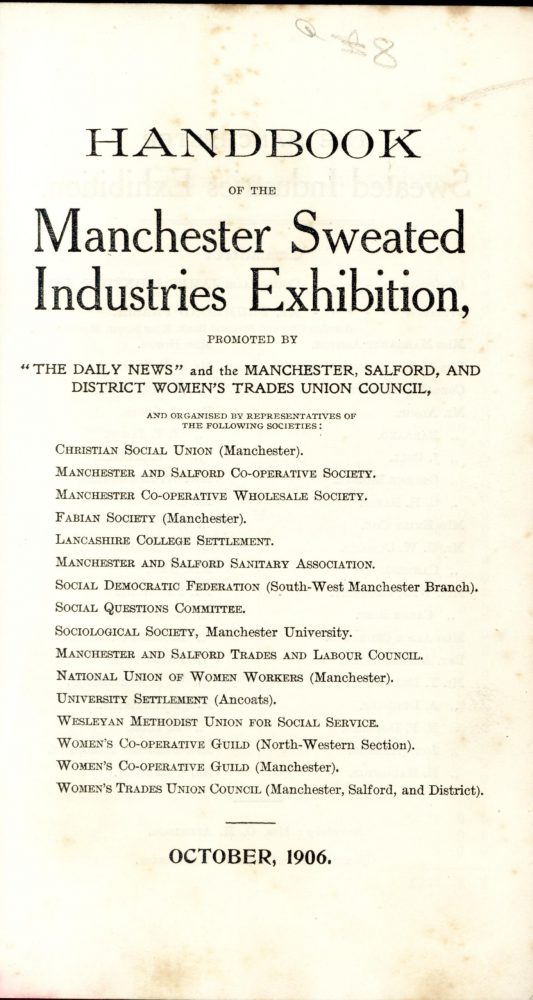

Campaigners to improve pay and conditions organised events such as the Manchester Sweated Industries Exhibition in 1906, which aimed to highlight the terrible conditions endured by “sweated” workers. The library is fortunate to have a copy of the exhibition handbook which was published in Manchester by the William Morris Press. The handbook contains information about the organisers, articles, a list of the lectures to take place at the exhibition and details of the industry stalls – painting a graphic picture of the grim work that poor people had to do to get by.

One of the main organisers was the Manchester, Salford, and District Women’s Trades Union Council, which campaigned to improve pay and conditions for sweated labourers, supported by a large committee of representatives from campaigning organisations. The committee raised £401 8s 6d from Guarantors and Subscribers, who included Julia Gaskell, the younger daughter of the novelist Elizabeth Gaskell. The event was promoted by The Daily News, a paper which campaigned against sweated labour.

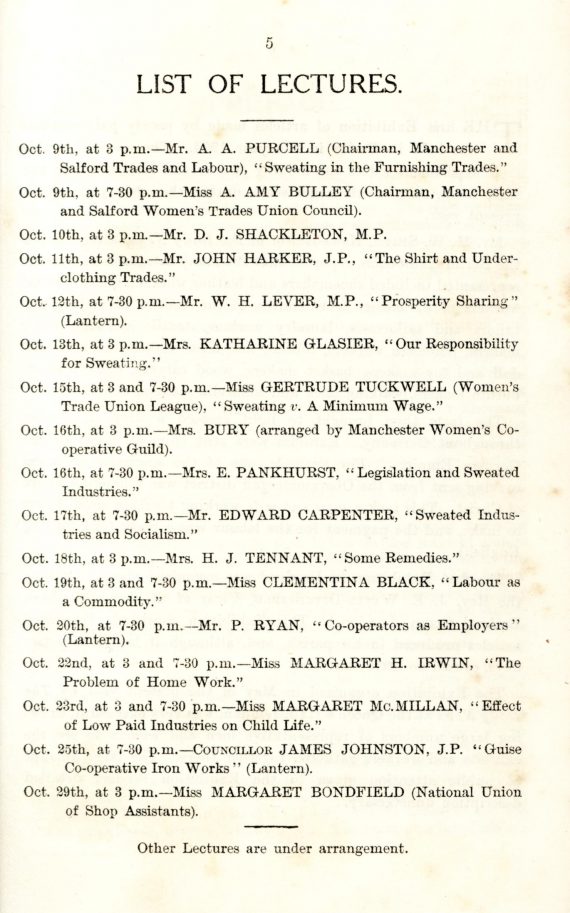

Afternoon and evening lectures, mainly by women, addressed different aspects of “sweating”.

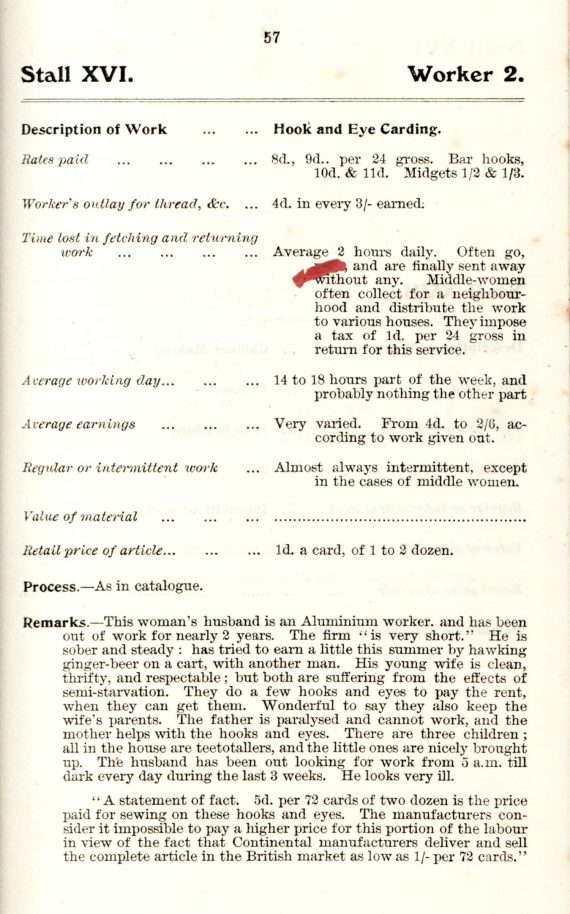

The handbook also describes some of the sweated industries. We learn that, in Birmingham, hook and eye carding is done by married women, widows or elderly spinsters and that 384 hooks and eyes linked together and stitched on a card earned ‘the munificent wage of one penny.’ This would only buy half a loaf of bread at the time and is the equivalent of 33p today. Child labour was common and children as young as 5 were brought to work. One mother set out the stark choice she faced: ‘You must either make the children work or let them starve.’

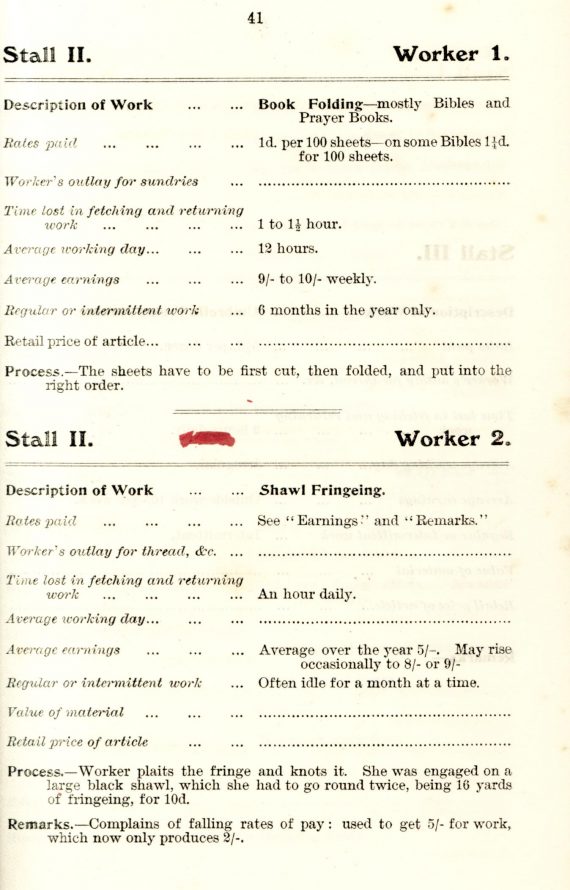

Desperately low pay was often reduced further as workers had to provide thread and other items they needed, and were not paid to pick up materials and deliver finished items. They worked long days when work was available, but it could be sporadic or seasonal. It is hard to imagine how the bible folders withstood the monotony of folding page after page of thin paper, in order to earn just 9-10 shillings a week.

The handbook also describes unbearable hardship at home, as whole families struggle to eke out an existence by carding hooks and eyes: the husband ‘has been out looking for work from 5am till dark every day during the past 3 weeks’, one page of the handbook reports, ‘He looks very ill’.

In the preface to the handbook, Mrs Sidney Web makes clear that consumers demanding cheap goods have some responsibility for the exploitation of the workers who make them:

We may ourselves never pay wages which we know to be miserably inadequate to the needs of life, but every day we use the articles for which such wages have been paid. We make use of matches and match-boxes, of buttons and hooks and eyes, of paper bags, and a thousand and one of the unconsidered manufactured trifles of daily life, with a faint wonder that things should be so cheap; while even for the things for which we pay heavily, the probability is that at one stage or another of manufacture sweating will have crept in.

Unfortunately we are still familiar with the term ‘sweatshop’ and the idea that the production work for goods we buy in the UK might be outsourced to countries where people work long hours in dangerous and unsanitary conditions for less than a living wage; but closer to home, could we even compare the sweated labour of Manchester in 1906 with the gig economy and zero hours contracts of 2018?

Articles in the handbook discuss remedies for sweated labour, including legislation and worker organisation. One writer sees hope in the growth of a public conscience which could lead to consumer action, although they also warn this is unlikely to happen in the near future. Reading the handbook, it’s impossible not to reflect on how far we’ve come, and how far we’ve still got to go.