- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

The Bees

Apiarists are keeping bees on city roofs and the bee is a recognisable Manchester icon that symbolises the industry and vibrancy of our city. We find bee images across the city, on Town Hall mosaic floor, the Palace Hotel clock, our coat of arms, bins and bollards and the facades of buildings. We can also find bees in the library’s collection which gives us fascinating insights into the development of the science of beekeeping.

Bee woodcuts

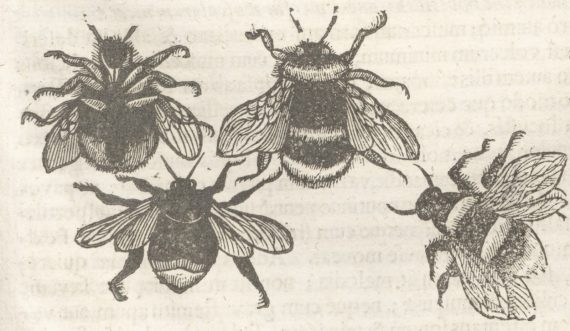

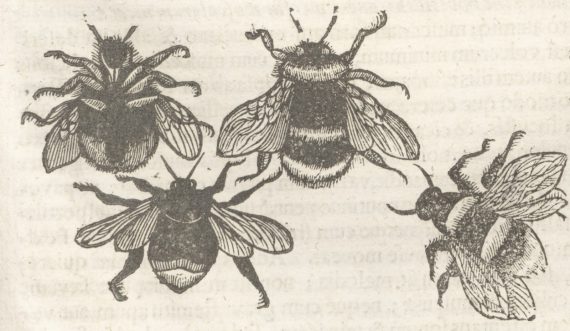

Woodcut of Bumblebees from Moffet’s Insectorum sive Minimorum Animalium Theatrum

Interest in entomology and writing on horticulture was increasing rapidly around the time the library was founded in 1653 and some of our earliest bees can be seen in the delightful woodcut engravings in Insectorum sive Minimorum Animalium Theatrum published in 1634. The title of this Latin text translates as ‘The Theatre of Lesser Living Creatures’ and one of the four authors, who all died before the volume was completed and published, was Thomas Moffett (1553–1604). Moffett was a physician and naturalist with a deep interest in entomology, a science which advanced from the 17th century as developments in dissection and microscopes enabled detailed anatomical study of insects. The many lovely woodcuts illustrating the Latin text include the depiction of bumblebees below. You can read more about this book in our previous blog here.

Bee super powers

People have had a relationship with bees since early humans discovered how to collect honey from wild bees. Apiary skills developed as ancient civilisations started to domesticate bees. Superstitions also abounded with some cultures believing in the supernatural power of bees. In Systema Agriculturae or The Mystery of Husbandry (1681), John Worlidge refers to the ancient belief that bees were portenders of either good or evil, and regarded as divine by some. Pliny regarded them as ‘augurs or presages’, stating that ‘bees rested on the lips of the infant Plato presaging his future eloquence,’ and:

‘That before the great battle, between Caesar and Pompey, when there were above 300000 men in the Field, in both Armies, besides the Aids of Kings and Senators, Swarms of Bees (not usual amongst Armies) presaged total ruine of Pompey and victory to Caesar.’

Profitable instruction

An estate, from Worlidge’s Vinetum Britannicum

Beekeeping gradually spread across Europe. Yeoman farmers and other country dwellers kept bees, and the reign of Elizabeth I saw the widespread construction of manor houses for the nobility and merchant classes usually with beehives on their estates. This increased interest in husbandry created a market for instruction books, which usually included a section on beekeeping, and the library is fortunate to have examples of these publications.

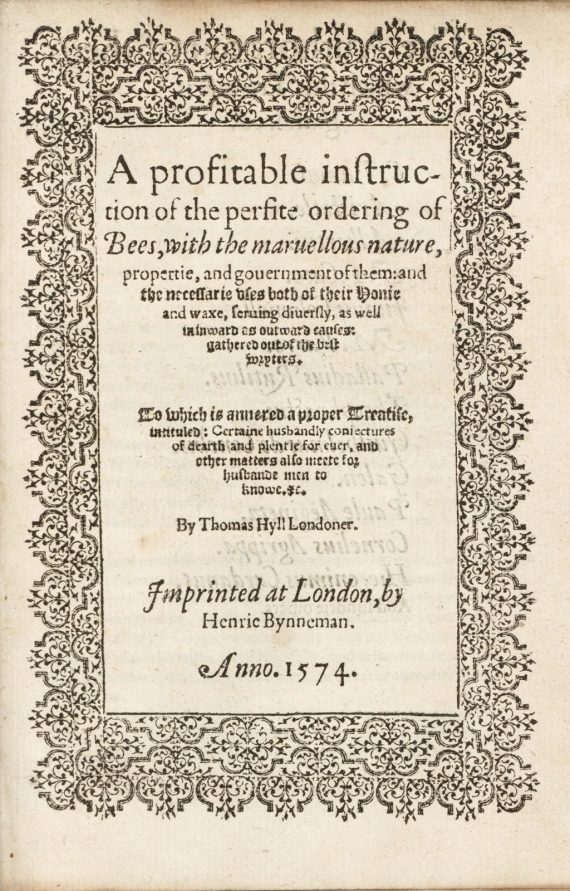

Thomas Hyll drew on the ancients, Pliny, Aristotle and others, as well as his own knowledge to write his treatise on bees, A profitable instruction of the perfite ordering of Bees (1574). This is an enlarged version of the author’s A most briefe and pleasaunte treatise, teachyng how to dresse, sowe, and set a garden (1558), the first book on gardening printed in England.

Title page – Hyll’s Profitable Instruction

In the 17th and 18th centuries improvements in microscopes enabled natural philosophers and apiarists to enhance their understanding of the anatomy and behaviour of bees. However, limits to their knowledge remained as we see in Hyll’s questions of ‘Whether the Bees drawe breath, or have anie blood in them?’

John Worlidge was an expert on English rural affairs and farming and his Systema Agriculturae or The Mystery of Husbandry (1681) is the third edition of the first systematic text to advise on arable and livestock husbandry. It was written for ‘the gentry and yeomanry of England’. Like others writing at the time, Worlidge stressed that you must observe bees closely to learn about them. In the section on bees in the library’s 2nd edition copy of Vinetum Britannicum or, A Treatise of Cider (1678), the cider section of his Systema Agriculturae expanded and published separately, Worlidge recommends building transparent hives with glass windows. He remarks that this is of little extra benefit to the bees but may not ‘incommode’ them whilst offering spectators ‘much pleaseure and delight to see these nimble creatures always in Motion.’

Be like a bee

Early writers often described the bee behaviour they observed in terms of human qualities and traits. Gervase Markham’s early book on farming, Cheape and goode Husbandry for the well-Ordering of all Beasts and Fowles and for the general Cure of their Diseases (1631), is based on his own experience of husbandry. It was written for ‘husbandmen’ lower in the social scale than the landed gentry and contains a short chapter on bees. He describes the bee colony as a kingdom:

‘They have a kind of government amongst themselves, as it were a well ordered commonwealth; every one obeying and following their king or commander.’

He also has a stab at the reason why bees might sting people:

‘… gentle and loving creature to clean sweet smelling men, but if a person is ill smelling they are malicious and will sting spitefully.’

In Melisselogia Or, the female monarchy. : Being an enquiry into the nature, order, and government of bees, those admirable, instructive, and useful insects, published in 1744, the Reverend John Thorley identifies many bee qualities: their labour and industry, patience and innocence, justice and honesty, temperance and sobriety, chastity, neatness and decency, sympathy and mutual assistance, sagacity and prudence, vigilance and watchfulness. He encourages his readers to learn from and follow the ways of the bees, adding a partisan spin in his citation of bee loyalty to exhort readers to support the king rather than the Jacobite cause:

‘Their great Affection, Love and Loyalty to their lawful Sovereign…all Royal Orders and Commands are most redily and cheerfully executed, chearfully and constantly obeyed, whether in swarming, in killing the Drones, or fighting with their Enemies, Etc. Nothing can tempt them to the least Act of Disloyalty; nor is there to be found so much as a single rebel in all the Community.’

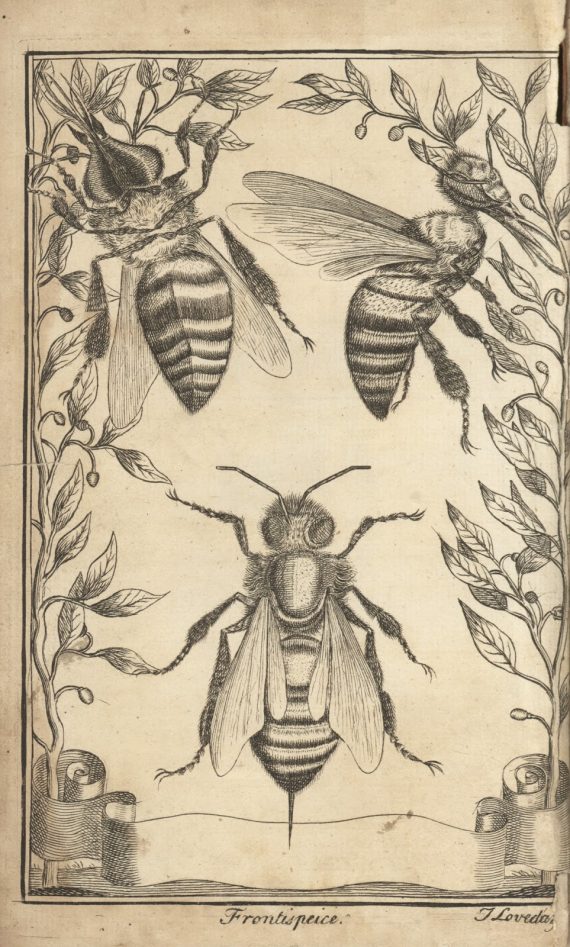

Bees – the frontispiece of Thorley’s Female Monarchy

Skeps to hives

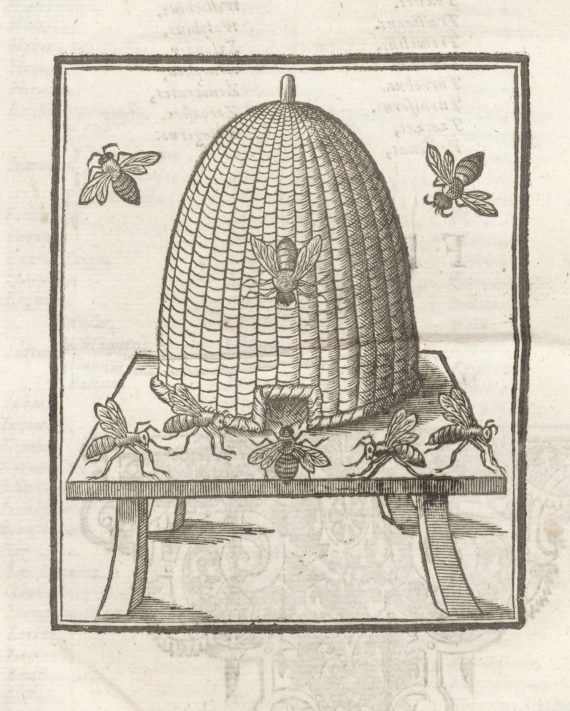

A skep from Moffet’s Insectorum Animalium Theatrum

Before the 17th century bees were kept in basic hives called skeps. These had to be destroyed to gather the honey, destroying the bee colony in the process, and forcing beekeepers to start with a new swarm each year. This started to change from the late 17th century when beekeepers started to see this as wasteful and cruel and began to search for less destructive ways of harvesting their honey. Worlidge discusses ways of harvesting honey without destroying the bees in Systema Agriculturae, but he is still not convinced that it is important to preserve their lives:

‘I judge it the most prudential way to have in your Apiary a sufficient stock of Bees kept for Breeding and Swarming, and another stock kept in large Glass-hives, whereof we have discovered for the raising of great quantities of Honey, which they will much better in those Hives; and I see no reason why we should judge it a greater piece of cruelty or inhumanity, to take away the lives of these creatures (who have so short and insensible a life and die so easily) for their Honey, than to take away the lives of any other Animals to feed on their Carkasses: which is daily done, and that with a very high degree of torture. Neither can it be any loss to the Beemaster, who may have an annual supply by his Swarming – stocks kept for that purpose ….’

Thomas Wildman is regarded as one of the leaders of the transition to a more humane and sustainable approach. His methods are set out in A treatise on the management of bees; wherein is contained the natural history of those insects; with the various methods of cultivating them, both antient and modern, and the improved treatment of them (1768). The King was a subscriber to this volume and Wildman begins the book with an address to the queen in which he commends his method of taking honey without killing the bees:

‘If the author pretends to any merit that might intitle him to so great an honour, it is in having discovered a method of preserving the lives of those innocent and useful insects, whose labour and industry has been hitherto the occasion of their death. And he therefore hopes that has contributed to put an end to the cruelty and ingratitude, which have attended the methods of taking their wax and honey.’

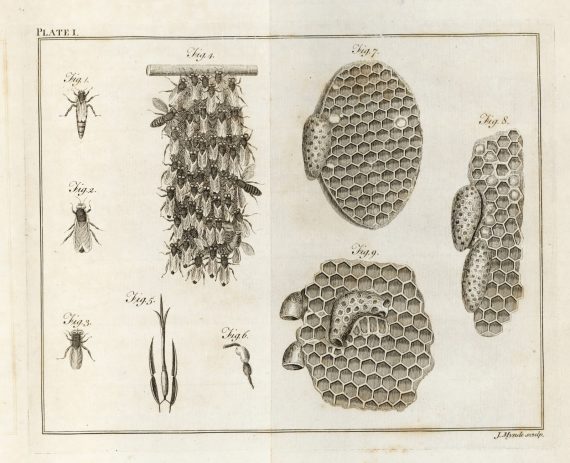

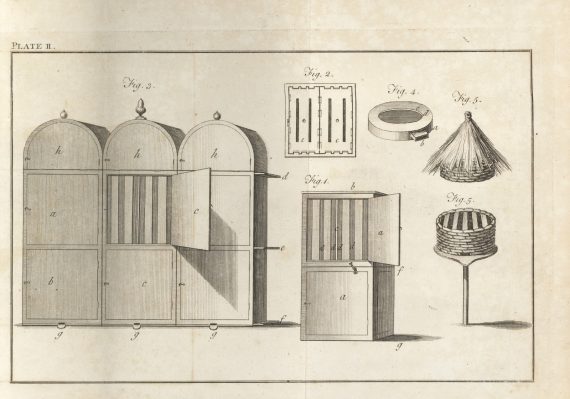

Hives from Wildman’s Treatise

Wildman drew on the work of other beekeepers as well as using his own observations to design hives using bars across the top or multi-storey hives that allowed the honey to be harvested without killing the bees. This marked the start of a transition in beekeeping methods to the modern methods used today.

Health and beauty

Early publications also advise on uses of honey, for example as a beauty product. The ladies companion: or, modern secrets and curiosities, never before made publick. : Containing, I. The art of painting, preserving and beautifying the face …. II. The art of preserving, beautifying, and painting the hair … III. The art of preserving and beautifying the teeth … IV. The art of beautifying the hands … V. The art of sweetning the breath … A book fitting all sorts of men and women whatsoever. The same never being reduc’d into an art by itself. The whole humbly dedicated to the faires, was published by Anne Baldwin in 1704.

Many recipes in this volume use honey. The section on hair urges the reader to use the distilled water of honey as ‘an excellent beautifier of the hair making them fair and weel coloured.’ Using this might be a pleasant experience, unlike the unspeakable recipe for thickening hair and alleviating baldness:

‘Take ashes of Bees half an dram, Mouse and Rats-dung, of each two drams; Honey, Oil of Rhodium, of each 6 drams ; mix and make an Ointment.’

Bees in the orchard, honey in the cider

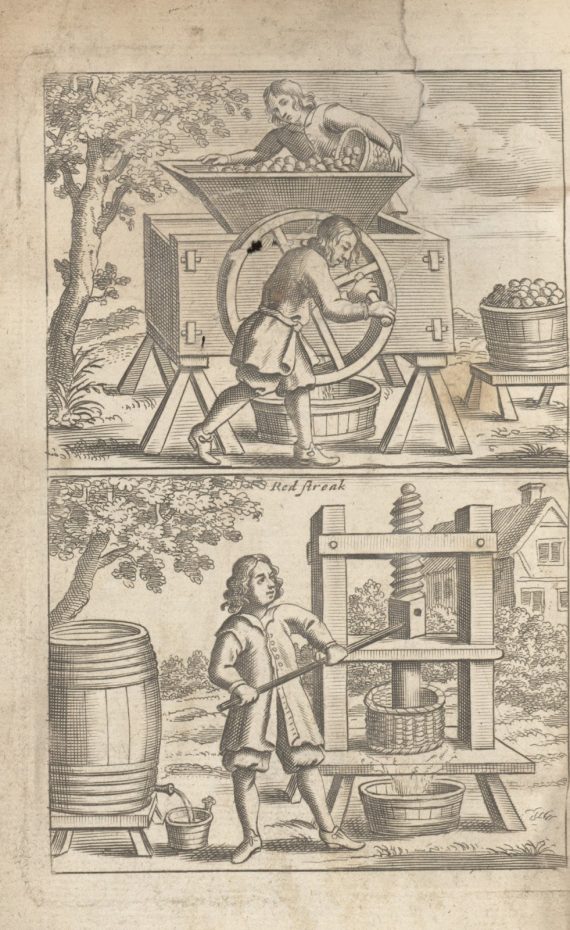

A drink might be the only way to recover from the rats’ dung ointment! There was very early understanding of the connection between bees as medieval abbeys kept bees for honey to make mead and other wines. Worlidge’s Vinetum Britannicum or, A Treatise of Cider (1678 ) sets out how to make and improve cider and other fruit-based liquors and includes an additional final section on keeping bees to pollinate fruit trees as well as produce the honey required for making liquors. The section ends with ‘A receipt to make pure Mead that shall taste like Wine.’

Worlidge’s Vinetum Britannicum

Cider making, from Worlidge’s Vinetum Britannicum