- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

Thomas Whitaker

Recently one of our readers was studying the works of Thomas Whitaker, an influential English clergyman, topographer, and antiquarian. As we have several works and the death mask of Whitaker in our collection we thought we would share his story.

Thomas Dunham Whitaker came from the Whitaker family of Holme near Cliviger, Burnley. He was born on 8 June 1759 at Rainham in Norfolk, where his father, William, was the curate. Thomas was educated by a series of clergymen until 1774, when he was admitted to St. John’s College, Cambridge. In November 1781 he took a law degree (LLD), and upon the death of his father in 1782, he went to live at Holme to manage the family estate. He was ordained in 1785, but had no clerical appointment until 1797 when he was made curate of the chapel at Holme on his own nomination, having himself bought the right to present to the benefice in 1788. From his early life, the Library holds a commonplace book including verses, notes on the New Testament and from law lectures he attended.

What remains of the Whitaker family estate at Cliviger

Dr Whitaker became vicar of Whalley in 1809, a benefice then worth about £100 a year. In 1818, Whitaker became the vicar of Blackburn and retained the livings of both Whalley and Blackburn until his death. At this time it was not uncommon for clergy and bishops to have multiple livings and to use curates to perform their duties when they were absent.

One of his greatest achievements was undertaking landscape ‘improvements’ in the Cliviger area, where he oversaw substantial planting of trees and other work to beautify the wild landscape. He planted about half a million trees between 1785 and 1815, and his work is still the prevailing influence upon the scenery in the valley, also winning the gold medal of the Society of Arts for planting 64,000 larches in a year.

His involvement in local life extended to politics and the suppression of disorder: he signed the printed resolutions of ‘a numerous and highly respectable meeting composed of the magistrates of the Higher Division of the hundred of Blackburn’ held at Burnley ‘for the purpose of adopting effectual measures, for the maintenance of the public peace, at this important crisis.’ A damaged copy of this rarity is held at Chetham’s, pasted into one of the scrapbooks given to the Library by the infamous Peterloo magistrate, W.R. Hay. Another pamphlet of 1817, printed at Lancaster, contains a speech by Whitaker ‘tending to support the existing laws and constitution of England’; another sign of the unsettled nature of the times.

Not content merely with changing the landscape, Whitaker now began to document his geographically huge parish and its long history in the shape of his exhaustive History of Whalley. He published it by subscription in 1801, and sales and interest were sufficient to carry it through to a second and third edition in 1806 and 1818. A further testament to the lasting value of the work is that the title and Whitaker’s main authorship was retained for the fourth, two-volume edition of 1872-6, enlarged and continued by Gough Nichols and Lyons.

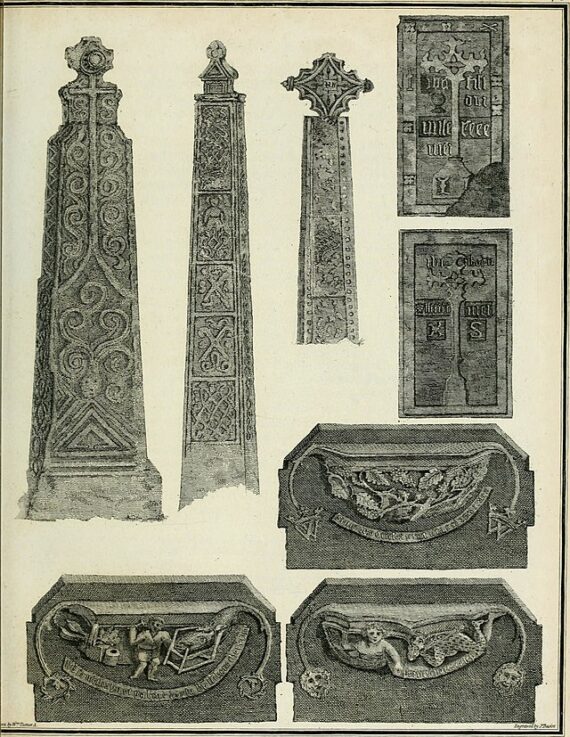

Engraving from An History of the Original Parish of Whalley, and Honor of Clitheroe, In The Counties of Lancaster and York.

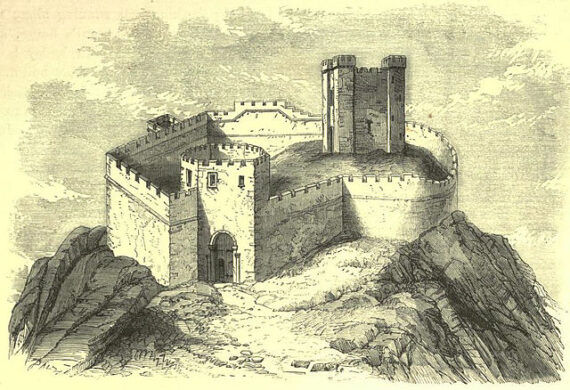

While its starting point is firmly embedded in the long-standing tradition of local antiquarianism, the History of Whalley represents a landmark in topogpraphy in terms of its more modern use of identifiable primary sources and breadth of scholarship, giving it lasting value into the present day. The book’s impact on the eye was much enhanced through a member of one of Lancashire’s most active antiquarian families, Charles Towneley, who had taken an interest in Whitaker’s writing from the first, and introduced Whitaker to the young J.M.W. Turner. The artist produced a series of watercolours of the landscape and antiquities that formed the studies for the fine engravings in the published work.

Whitaker’s success with his publication on Whalley seems to have prompted him to reach further afield for his next books. He continued in 1805 with a History of Craven (it sold well enough for a second edition in 1812), and in 1816 came Loidis and Elmete, a history of the area around Leeds, including lower Wharfedale and Airedale; finally in 1823, after his death, the History of Richmondshire appeared, the first and the only completed part of a history of Yorkshire, which would have been an ambitious undertaking indeed. Turner’s illustrations for these later works are now perhaps the most significant thing about them. Whitaker also published numerous minor articles in general interest journals such as the Quarterly Review, but the work on Whalley is the foundation of his reputation, and set the standard for other works of local history. Chetham’s Library’s very active collecting on Lancashire and Cheshire local histories and topographies reflects the many authors who turned to Whitaker as a model of how to write such books.

Engraving of Clitheroe castle after J.W.M. Turner

In our collection we are lucky to have original copies of the first, third and fourth editions of A history of the original parish of Whalley : and Honor of Clitheroe, in the counties of Lancaster and York with the engravings by Turner, in addition to his other histories; but perhaps the most peculiar item, and certainly a unique one, is his death mask, which now looks out onto the Priests’ wing of the Library.

You can find records for all the Library’s holdings by or about Whitaker in our catalogues at . The best single source to find out more about him is Alan Crosby’s article for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, to which we gratefully acknowledge our debt.

2 Comments

Jeremy Howarth

I was interested to read this piece on Dr. Whitaker, who was a knowledgeable contributor to the history and topography of South East Lancashire. He took a particular interest in the history of my family (the Howarths of Great Howarth, near Rochdale) contributing family pedigrees (included after p. 404 of the fourth (1876) edition) and also taking part in the long running debate over the possible connection between the original Howarth family and the noble Howard family (pp. 444-45).

His History of the original Parish of Whalley and Honor of Clitheroe … contains much valuable information on the history of the area but it should be noted that Whitaker’s work was sometimes repetitive and was far from error free and that he allowed at least one curious personal grudge to cloud his judgement and dominate his treatment of certain topics.

Whitaker’s written work was extensive but according to the Preface written in the 1872 by the editors of the fourth (posthumous) edition of his History of the original Parish of Whalley … (p. x of volume I) Whitaker was reluctant to put in the hard work (the limae labor) to ensure that his references and quotations were accurate. While the editors stressed that his work was still a valuable account of the area’s history and topography they stated that the verification of quotations and references had been found to have been done by Whitaker with … the carelessness of genius. It was a strong cautionary note that Whitaker was not a reliable authority. While it is almost inevitable that any substantial detailed history contains some errors, it is evident that Whitaker’s work was particularly prone to errors emanating either from his unwillingness to do the necessary research or to check the details.

However Whitaker also curiously bore a grudge against at least one historian. His most remarkable grudge was that levelled against the distinguished, antiquarian, historian, lawyer and genealogist Sir William Dugdale, who was Garter King of the College of Arms 1677-1686 and published a number of scholarly works including the Monasticon Anglicanum (with Roger Dodsworth), the Origines Judiciales and the Baronage of England, all significant and original works. Indeed Canon F.R. Raines (a co-founder and great servant of the Chetham Society) described the Monasticon as a work of national importance, second only to the Domesday Survey. Dugdale has always been considered to have an excellent reputation for accurate scholarship and is to this day regarded by the College of Arms as one of its most eminent former officers.

It therefore remains an unexplained mystery as to why Whitaker chose to attack Sir William Dugdale on a number of fronts. He stated in terms that Dugdale had taken advantage of his co-author Roger Dodsworth’s recent death in 1654 to claim an undeserved part in the publication the Monasticon Anglicanum. Whitaker’s view was that Dugdale did not deserve to be treated as a co-author; however this opinion had been roundly rebutted by leading scholars of Dugdale’s period, such as Sir John Marsham, who wrote the Preface or Propylaion to the Monasticon, William Somner, the Anglo-Saxon scholar, Dr. Ralph Bathurst, F.R.S., and the famous antiquary Anthony à Wood. In the 19th century Canon Raines wrote … Great injustice has been done to the memory and labour of Dugdale by Dr. Whitaker [and Mr. Gough] who attribute the whole merit of the undertaking to Dodsworth. There seems to have been no logical reason to explain why Whitaker sought to criticise Dugdale on this issue.

Whitaker also attacked Dugdale for publicising in detail and at some length his opinion that the noble Howard family were descended from the Howarth family of Lancashire. Dugdale and the head of the Howarth family in 1665, Dr. Theophilus Howorth, himself a noted genealogist, co-wrote the Howarth family pedigree based on the family’s numerous deeds and evidences, which showed that Justice Sir William Howard, who died in 1308 and became the first of the noble Howard family line, was the son of a Howarth younger son. This original pedigree was kept by the Howarth family, was transcribed by Canon Raines in the 1840s and was published in 1877 by a Howarth descendant (Sir Henry Howorth). The deeds and evidences were seen by numerous respected historians and scholars including several Lancashire historians in the 19th century. The deeds were inventoried in the 1930s by the University College of Hull and were undoubtedly genuine.

Whitaker however asserted that Dugdale’s comments had been written and his judgement formed … without an iota of evidence in their support, a remarkable statement in the context of the numerous deeds and evidences quoted on the pedigree, which Whitaker admitted he had seen. There was no doubt scope for scholarly debate on a matter of this type but Whitaker seems to have taken a quite extreme line by refusing to accept that there was any evidence to support Dugdale’s view. Again the question has to be asked – why did Whitaker take such an uncompromising line against a scholar and genealogist of undoubted merit?

Whitaker also asserted that the arms of the Howarth family bore no relation to those of the noble Howards, when in fact some of the Howorth arms used from the 15th century were very similar to those of the Howards. He also asserted that Dugdale had resiled from his opinion of the Howards’ ancestry in his later entry in the Baronage of England, when that entry in fact left open the possibility of the Howard name being taken from a place (i.e. Great Howarth). Conducting research of this type in the 19th century was no doubt more difficult and time consuming than it is now, but again it is surprising that Whitaker did not even admit the possibility of contrary evidence when he made his statements.

The eminent scholar Richard James visited the Howarth home, Howarth Hall in the 1630s and evidently saw the Howarth deeds on that occasion. James’s Iter Lancastrense, was published in 1636 and was edited by Thomas Corser and republished for the Chetham Society in 1845 and again (by Alexander Grosart) in 1880. These all confirmed Dugdale’s judgement and referred to specific Howarth deeds. Whitaker however dismissed the Iter Lancastrense and ascribed the Howarth family’s belief to … the capacious faith of Dugdale. Again Whitaker declined to accept the possibility of a valid view contrary to his own and attributed no value to the work of James, who was a scholar of high repute and a colleague of Sir Robert Cotton. James would have had no interest in supporting an unjustified point of view.

It seems that there must have been some underlying reason for Whitaker to state his trenchant views, which contradicted both the opinions of serious scholars and the evidence. He made in the early 19th century a series of unjustified criticisms of the scholarship of this well respected historian and author, who had died in 1686, for which I can find no logical reason. I can find nothing in Dugdale’s extensive work which might have offended Whitaker. His treatment of the Abbeys of Stanlaw and Whalley, in which Whitaker had an obvious interest appears to be accurate and unexceptionable.

Maybe Whitaker’s animosity derived from Dugdale failing to include the 17th century ancestors of Whitaker in his Visitation of Lancashire. Whitaker was descended from a family with possible claims to gentry status, having lived at The Holme, near Burnley since the 15th century; however there is no known evidence of the Whitakers having submitted a pedigree at any of the Lancashire Visitations. It is just possible that the Whitaker family’s connection to Professor William Whitaker, a prominent Elizabethan Protestant divine or his son Alexander, who emigrated to Virginia and converted Pocahontas to Christianity, may have offended William Dugdale.

There may however be some quite different explanation. If any reader can throw light on this topic it might resolve a long standing mystery.

ferguswilde

Thanks, Jeremy! With local history comes local politics, and with genealogy come disputes! Dugdale, like Whitaker, still comes in very handy in the later and posthumous editions, but it looks as if personal prejudices and feelings won out over evidence. We wouldn’t have guessed at any of this without your remarks; readers please contribute if you can.