- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

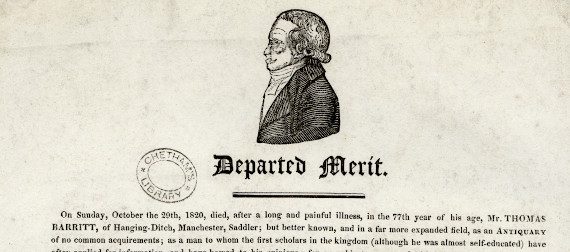

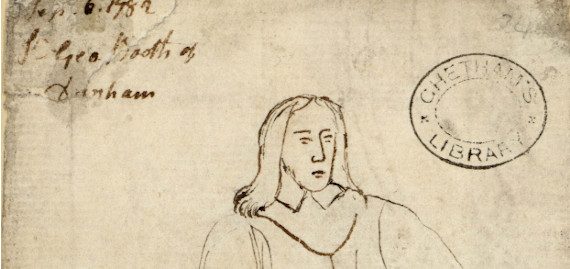

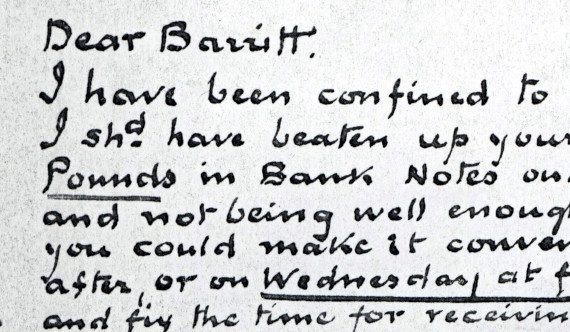

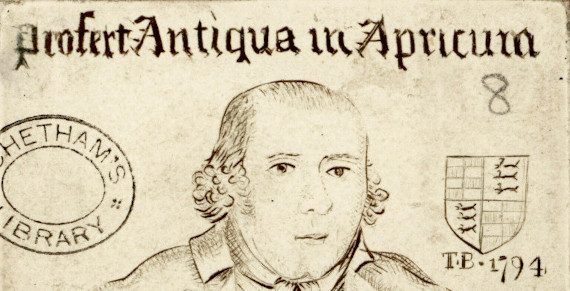

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

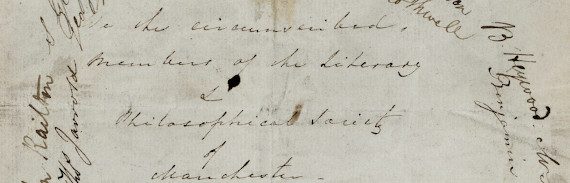

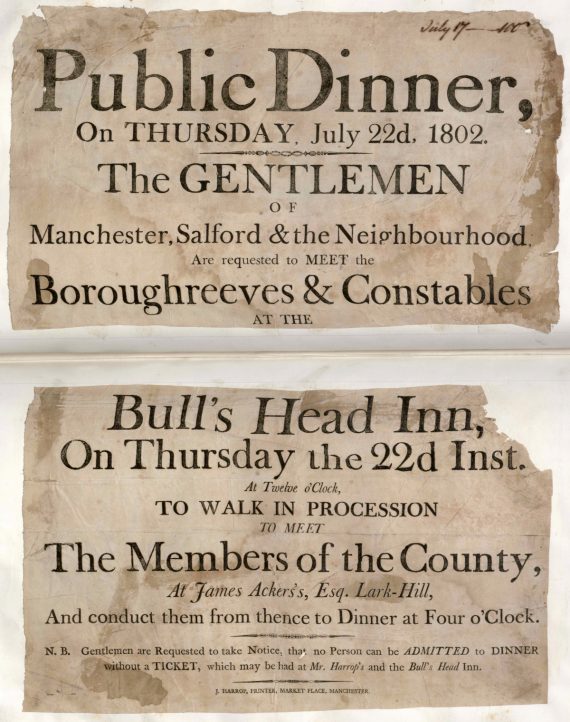

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

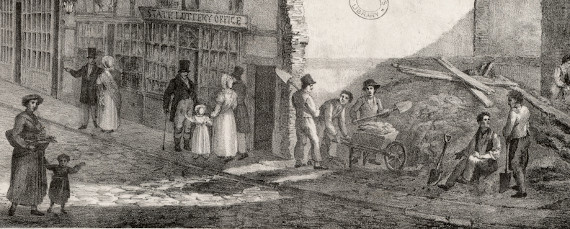

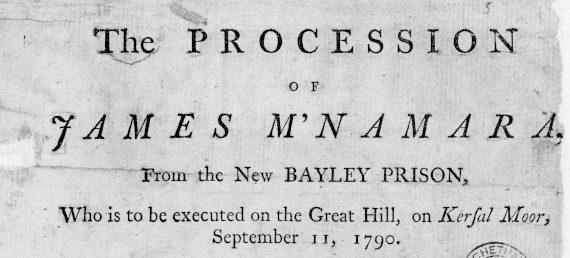

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

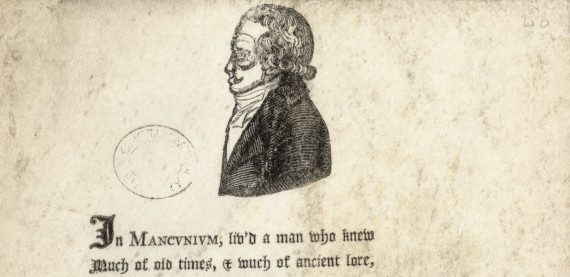

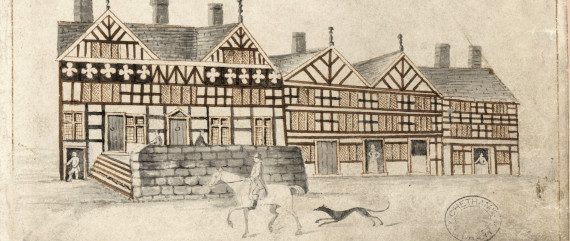

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

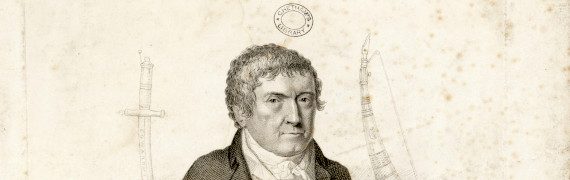

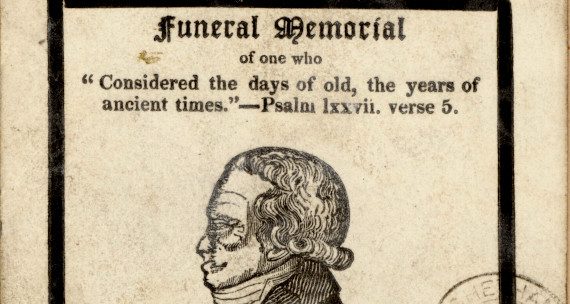

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

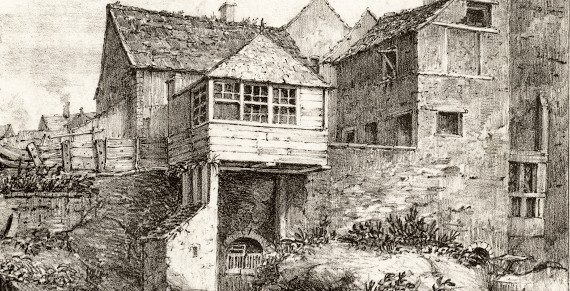

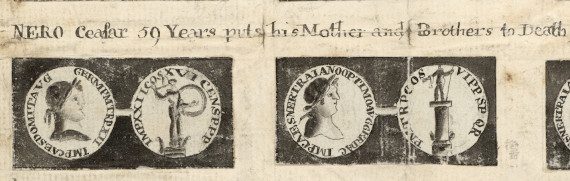

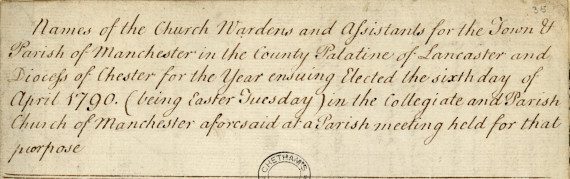

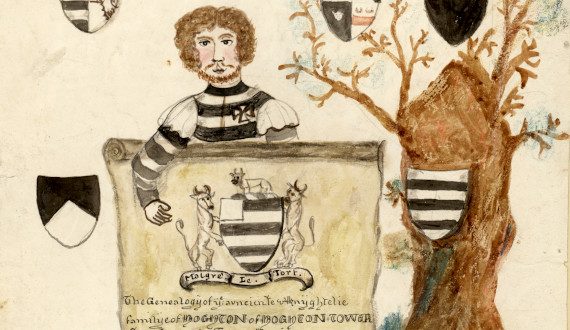

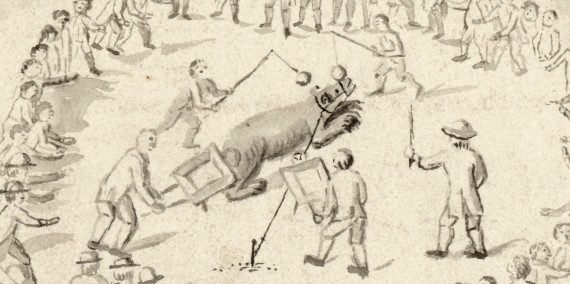

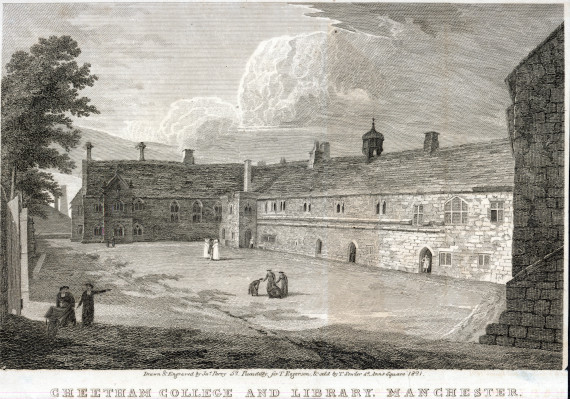

The Manchester Scrapbook

A guided browse through a slice of Manchester history

For #MuseumFromHome in May 2020, and as a way of being in while we’re out, we decided to Tweet and Instagram an image every weekday from the Manchester Scrapbook, given to the Library in 1838 by its compiler, Francis Egerton, 1st Earl of Ellesmere (good Wikipedia bio here). There’s a little more on some of the Library’s scrapbooks here. As posts like that tend to get buried, and because people seem to have been enjoying the images, we’ll add the items here as they appear on social media. Click through for the full image. Apologies to those with a stronger level of interest that we’re not always able to give you chapter and verse on some of these – we can’t get at the usual lists and research materials just now. We’ll make the images a permanent part of the website as soon as time permits, and bring out some of the many stories they tell. Please do contact us, however, with any questions (better still, answers) and we’ll try to answer them or incorporate them as circumstances permit. We’ll just give the captions as posted at present, and hope to add detail and more interpretation in the future. So that you’ll see the newly added images first, we’ll follow Hollywood practice and announce things in reverse order; please go to the foot of the page and scroll up if you’d prefer to start at number one. We’re returning to this Scrapbook series for 2021, and hope this will beguile a few minutes of lockdown for you.

152 : Manchester Academy Ticket

Not a ticket to the Manchester Academy you may be thinking of if you’ve been to gigs at the University of Manchester in the last few decades. There have been a number of organisations that might have been referred to as the ‘Manchester Academy’, but here we seem certain to be dealing with the organisation whose unhappy history is represented by this note in Axon’s Annals of Manchester under the year 1805: ‘Mr W.M. Craig attempted the formation of a Manchester Academy for the Promotion of Fine Arts, but the attempt failed’. William Craig was planning and attempting to raise public interest in a fine art academy basing its scope on that of the Royal Academy itself from 1802 onward. The organisation got a far as issuing its printed rules in 1805, although the formal title differed in them from that noted by Axon: Laws and Regulations of the Manchester Academy for Drawing and Designing. The ‘Admit M ….. a student’ seems to suggest that honorific titles for either sex might be used. The engraving is signed ‘Lee’, but Manchester’s celebrated wood engraver Stanley Lee was not born when this ticket was issued. We haven’t been able to tie the name to an identifiable individual. Does the rather exhausted and drooping-looking muse on the left reflect Craig’s exhaustion with trying to get the Academy off the ground?

151 : Vittore Zanetti, Repository of Arts

This beautiful illustrated admission ticket to the ‘Manchester exhibition of ancient and modern paintings’ was not entrusted to a Manchester engraver, but to F. Eginton of Birmingham, as the tiny signature underneath the studious cherubs tells us. Eginton was active in the 1790s and early 1800s and a capable worker with many larger commissions to his credit. The scene he depicted, like the foundry and and factory bill-heads we’ve been looking at, illustrates some of the many strings to the bow of Vittore Zanetti and his family and the Zanetti and Agnew firm that did so much for those who would have identified themselves as Manchester’s patrons of the arts. Zanetti’s firm advertised variously as carvers and gilders, looking-glasss and picture frame manufacturers, thermometer makers and print sellers. The scene here also brings in telescopes, spectacles, artists’ materials, what looks like music manuscript paper, thermometer barometers, a globe, and – we think – a compass: a ‘Repository of Arts’ indeed! Thomas Agnew (1794-1871) joined Zanetti as an apprentice, and from 1817-1828 the firm was known as Zanetti and Agnew. When Vittore retired in 1828, Joseph Zanetti became junior partner, and with this rebalancing of seniority the firm changed its name to Agnew and Zanetti. After Joseph’s departure in 1837 the company became known by the Agnew name alone and continued with the family name until. The partnership were active publishers, often working with Joseph Pratt of Chapel Walks as their printer. They produced the first issue of the Lancashire Antiquarian Society’s Transactions in 1829, numerous auction catalogues for the sales of private house collections, and the voluminous (and still much used) History of the foundations in Manchester of Christ’s College, Chetham’s Hospital, and the free Grammar School by Samuel Hibbert. Agnew’s shifted their focus of attention to London in 1860, and the family name survives today in Thomas Agnew & Sons following the private sale of the firm in 2013.

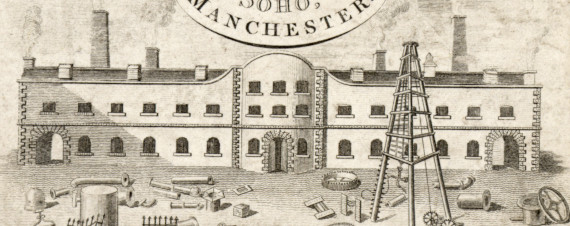

150 : Peel & Williams, Iron Founders

The tantalisingly named J.T. Slugg wrote in 1881 in his work Reminiscences of Manchester of Fifty Years Ago that ‘the most noted engineers of the day were Peel, Williams and Peel, of the Soho Foundry, Ancoats, and Galloway, Bowman and Glasgow of Great Bridgewater Street.’ We have a bill-head here from the former, known before 1825 as Peel & Williams. The little cameos of the Phoenix and Soho Foundries are the centre of their business as ‘Iron Founders, Steam Engine Makers, Cotton and Worsted Roller Manufacturers &c.’ and the bill provides for specification of the goods, their weight in tons, hundredweight, quarters and pounds, and their prices and totals in pounds, shillings and pence. Like the other foundries we’ve seen, yet on a grander scale, they existed primarily to furnish the cotton manufacturer of Lancashire (and the wool worsted manufacturers of the West Riding) with the machinery to set up the ever larger steam-driven, fireproof mills of the age. The firm was to prove a long lasting and successful one; Slugg’s footnote tells us ‘Mr George Peel still survives, having been born in Halliwell Street, in 1803’. This George Peel (junior, son of George senior, the first Peel in the company name) was cousin to the towering figure of Sir Robert Peel. The firm was established and active by 1800, and perhaps their most significant work was that of providing new Watt-pattern static steam engines to provide the power to colliery and to textile mill machinery. William Ward Williams (b. 1772) was the more experienced in the iron founding trade, having been through a couple of short-lived partnerships before setting up with George Peel at Miller Street. Musson and Robinson, who trace the history in Science and Technology in the Industrial Revolution, propose that Peel may have been more important for the capital he and other members of the family brought to the table than any knowledge of iron founding. There’s an excellent summary history on the invaluable Grace’s Guide, including specimens of the firm’s early advertising, such as this from 1802:

1802 Advertisement: ‘JOURNEYMEN IRON-FOUNDERS – Good, Steady Hands, will meet with a permanent Situation, and liberal Wages, by applying to Messrs. Peel, Williams and Co. iron-founders, Manchester.’

The company’s steam engines appear in advertisements from the sales of mills all over the area, a testimony to how central Peel and Williams engines were to the mass production factories that were to dominate Manchester and region’s nineteenth century.

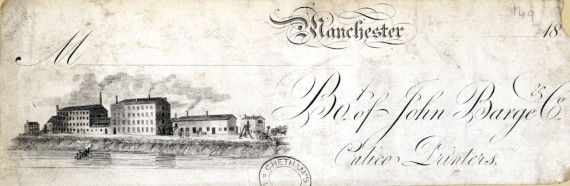

149 : John Barge & Co, Calico Printers

Re

With this bill-head we find ourselves with one of Manchester and district’s most important and widely exported product, printed cotton calico cloth. Following the invention of roller printing of dyes onto the cloth in 1783, replacing blocks that required manual aligning, the trade became ideal for the kind of mass production already beginning to dominate spinning and weaving of cotton. (See an excellent blog by Sue Wilkes here.) This brought the price of patterned fabric within the reach of a much wider domestic and international market, and the trade flourished. John Barge’s works were at Lower Broughton, and became a concern involving several members of the family. Their warehouse was on Peel Street. John Barge was, like the engraver Bottomley, a member of Salford’s Swedenborgian New Church and was a founder member of the committee charged with setting up a New Church denominational day school in 1824. Companies such as Barge & Co. were large concerns, and had political and social as well as economic effects. The company numbered a former MP on their staff of cashiers.

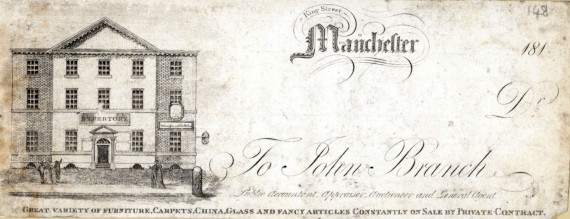

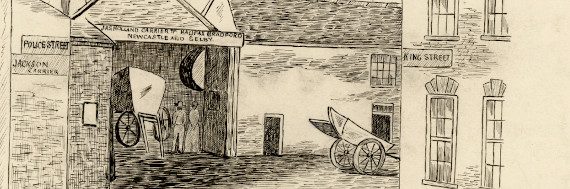

148 : John Branch, Auctioneer

John Branch’s grand ‘Repertory’ on King Street is today’s bill-head, again printed to serve the period 1810-19. The image of the splendid pedimented premises provided by the commercial artist has admiring passers-by pointing up at the business. There’s certainly plenty to admire: Branch is a ‘Public Accountant, Appraiser, Auctioneer and General Agent’, organising sales of a ‘Great Variety of Furniture, Carpets, China, Glass and Fancy Articles Constantly on Sale by Private Contract.’ A John Branch, perhaps the grandson of our John, was acting as an auctioneer in Liverpool as late as 1872. As further evidence of his diverse activities, our John Branch was also the business partner of steel maker James Jackson between 1802 and 1804. What is hard to read in the scale of image we can conveniently provide on the web is the microscopically small (yet perfectly engraved) plate on the right-hand side of the house that lets us know Branch is also an agent for the Albion Fire and Life Assurance Company, a major national insurance concern founded in 1805 and bought out by Eagle Insurance in 1858. Auctions, often ordered by courts in cases such as bankruptcy as well as by private individuals seeking to liquidate assets, played their part in managing the burgeoning commercial life of the Georgian town; all the more was insurance increasingly a vital part of protecting the increasingly large scale investments that were required in setting up the mills and foundries whose bill-head productions we have seen in the last few posts.

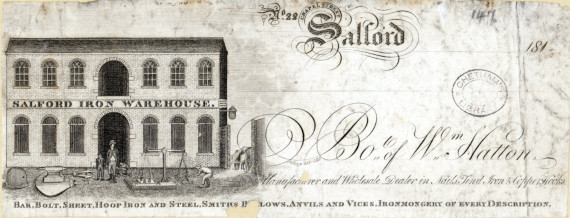

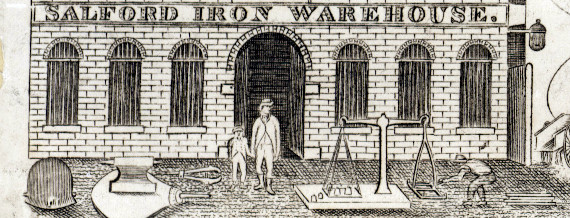

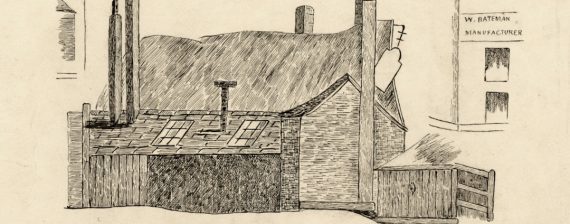

147 : Salford Iron Warehouse

We’ve seen an earlier form of this bill-head at number 133, and met the Hattons again at number 140. With this cutting, we’re lucky to have a more complete form of the head, and with that comes a great deal more information: the full address at 22, Chapel Street, Salford; that the batch was printed for use in the decade 1810-19; that William Hatton’s description of his business at the warehouse is that of ‘Manufacturer and Wholesale Dealer in Nails, Tin’d, Iron & Copper Hooks, Bar, Bolt, Sheet, Hoop Iron and Steel, Smiths Bellows, Anvils and Vices, Ironmongery of Every Description’. The image is signed by Alsope (whose work we saw for Hatton and Bowker’s Eagle Foundry at number 140), and he has evidently been asked to re-work the copper plate from which the bill forms were printed. The father and son looking about them in front of the main door to the warehouse, and the figure of the worker remain much the same, as does the repertoire of goods. The plate has much more sophisticated shading than before, however, and the pair have now acquired a dog. Impressively, given the tiny space, Alsope has added the street-sign ‘Back Water Street’ to the plaque on the right-hand gable end of the warehouse. These essentially ephemeral receipts and bills continue to give us information we could often get nowhere else.

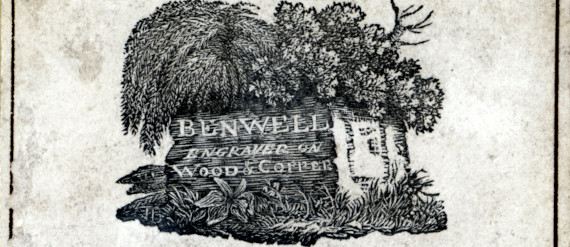

146 : Benwell, Engraver on Wood & Copper

J.M. Benwell makes his offer of artistic services to the public in a rather franker way than we have seen in the case of William Orme, and even provides some price guidance in his advertisement. It might surprise some to find that it cost more to provide a portrait of your horse than of yourself or those dear to you; presumably the human likenesses are limited to the profile, or perhaps don’t demand ‘the greatest exactness’. In terms of techniques for printing, he offers both wood and copper engraving. Engraving on copper plates inolved an intaglio method of printing, in which the ink for transfer to the paper was held in the grooves cut by the engraver in making the design, and needed to be printed in a special press that applied high pressure to push the fibres of the paper down into the cuts. This method could not be used in the same press as the moveable types of letterpress, the main means of printing language material, and if letterpress and engraving were needed on the same sheet, it would have to go through both processes separately. Woodcuts, on the other hand, involved cutting away the wood along the grain of a block, removing everything that was not required to print. It could be printed in the same process as letterpress by making the woodblock the same height as the moveable types, but it was not capable of representing the fine detail that copper engraving would. Wood engraving, by contrast, involved cutting the design into the end grain of a suitable hardwood such as box-wood with engravers’ fine tools, and could both accept fine detail and be printed with letterpress. That’s exactly what we see here, with M. Wardle including two of Benwell’s wood engravings with the letterpress to produce this attractive advert in a single pass through the conventional printing press. This was the age of wood engraving par excellence, as one of its earliest and most talented proponents, Thomas Bewick (1753–1828) was leading the way with his beautiful representations of the natural world.

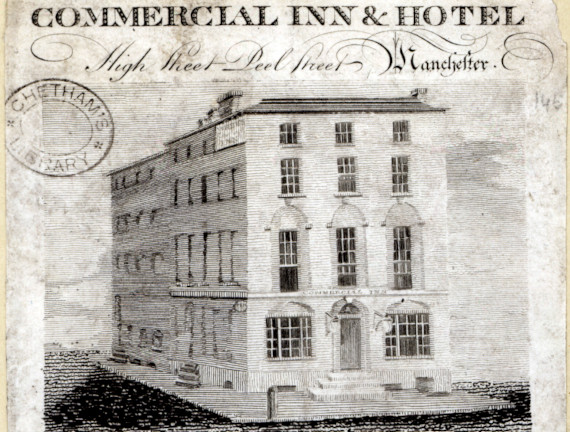

145 : Commercial Inn & Hotel

This pretty little advertisement presents a glimpse of another facet of the life of Georgian Manchester, the growth of business travel. The factories and foundries we have seen so far had to send their representatives out for all kinds of purposes: sales, buying, meetings were a staple then as now. In the pre-railway age, H. Webb has evidently tried to provide everything the traveller or local businessman might need, from overnight accomodation to meeting rooms to coffee room. No mere provincial coffee room, either, but one with the truly metropolitan feel of the ‘London Coffee Rooms’. Webb is careful to try to tempt those arriving from the capital or elsewhere on the stage coach routes by assuring them there will be the staff on hand at all hours, and provides stables and ‘carefull Drivers’; were reckless ones widely feared? The almost microscopic signature of the engraver, ‘Bottomley sc[ulpsit]’, seems likely to relate to the family of George Bottomley (b. 1793), of Rusham Lane, who was a worshipper at the Swedenborgian New Jerusalem Temple in Salford. He and his father were both engravers, and George’s large family were baptised at the Temple.

The Commercial Inn must have stood approximately on the red dot, fronting High Street. Detail from 1824 Pigot plan

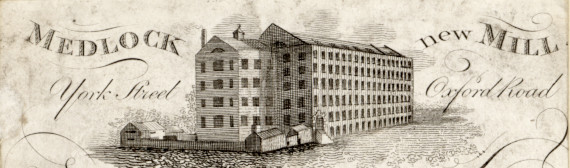

144 : Medlock New Mill

This bill-head takes us into the realms of the new and increasingly dominant large, purpose-built cotton spinning mill of the kind that the name Manchester conjures up for many. With six storeys, a large engine house containing the races that took the steam power to the various floors, and an impressive floor area, the building has the look that came to typify Manchester mills and those in towns such as Oldham. Only the hipped roof, as opposed to the later flat, water reservoir room distinguishes it from mills being built a century later. The bill-head locates it for us on York Street and Oxford Road. Thanks to some careful work by David R. Bellhouse, we can also date this accurately to between 1806, when the historical David Bellhouse extended his construction business as a partner in the construction and management of the Medlock New Mill, the name for both the buildiing and the business partnership, and 1819, when the Runcorn, Bellhouse and Runcorn firm was dissolved. Bellhouse went on to expand the firm with his sons as partners, and added two further mills to the same site before 1851, a complex that became known as Mynshull Mills. At the time this attractive little picture was drawn, the working day was fourteen hours, with a six day week.

143 : William Orme, Drawing Master

So used are we now to being able to create and distribute full-colour images with equipment that fits in a pocket, it can be a little hard to remember that capturing any object or scene relied entirely on the skill of human hand and eye. Reproducing such an image relied on a highly perfected, but also highly demanding, set of tools and techniques involving printing from blocks and plates, and required equipment, training and experience. The drawing master played an important part in cultivating the skills of the artist. Those who hoped to live by their drawing skills (such as some of the commercial artists whose work we have been seeing) were perhaps outnumbered by those learning to draw as a polite accomplishment. Titles such Every Lady her own Drawing Master (surely no coincidence that it was published by Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown in 1818) attest to the desire of the leisured classes to use time creatively. William Orme (1771–1854) was the child of another Manchester fustian merchant, Aaron Orme, and one of at least thirteen. Other brothers included Daniel and Edward, also involved in the art world and in publishing. All three moved between Manchester and London during their careers. Edward published William’s Rudiments of landscape drawing, and perspective dedicated to the Society for the Encouragement of Arts &c. &c. in 1802, and his Studies from nature : arranged as progressive lessons for instruction in the art of drawing landscape in 1810. An 1806 print after an original by Orme tells us that he must have been present (or at least so in vivid imagination) at Nelson’s funeral, and other watercolours including one of a romantic looking Collyhurst survive in various collections. The smiling and beatific muse, her portfolio no doubt full of beautiful work produced under William’s tutelage, looks lovingly out over the idealised landscape; Ardwick itself was indeed green at this point, so perhaps Orme has not overstretched himself in this invitation to would-be artists.

142 : Whitehead and Co., Brass and Iron Founders

We’ve already seen evidence of the growth of the iron foundry trade in numbers 133 and 140, and here with David Whitehead and Co we have another substantial firm, this time including brass casting, that grew up to service Manchester and district’s manufacturing industry and its economic hinterland. As with Hatton and Bowker at 140, the representation of Whitehead’s yard is filled with the products needed for the steam mills of the Georgian age as well as the domestic items wanted by their owners. The splendid Grace’s Guide, while regretting that ‘little is known about this short-lived company’ has gathered together the historical record of the firm, which built its works on a green-field site off Ancoats lane near the Ashton canal, built up some formidable equipment and resources, but did not survive the death of David Whitehead in 1807. When we hear about the site as it was sold to Peel Williams in 1810, the advertisement gives us a fascinating snapshot of the metal-working industry in the town:

‘Extensive Iron Foundry at Manchester. To be sold or lett on advantageous terms, all that capital and extensive Iron Foundry called the Soho Foundry heretofore occupied by the late firm of David Whitehead and Co. The foundry is 75 yards long by 25 wide; contains air-furnaces, cupolas, stoves, cranes of extraordinary power, an excellent smithy and finishers shop, and extraordinary well-lighted patten-makers and turners shop, extending 100 yards in length. Adjoining the foundry is a most complete Boring-mill and Turning shop, replete with every apparatus on the very best principle for boring and turning every kind of heavy or small iron and brass work. The Boring-mill and Turners shop are worked by an excellent steam engine, of 18-horses power, which also works the blasts for the cupolas; and there is additional power which may be applied to other purposes. There is an extensive yard, stable, cart-house, sheds and other conveniences; and also six cottage-houses for the accommodation of workman belonging to the foundry. The premises have likewise belonging to them a commodious Wharf on the Bank of the Ashton Canal, which communicates with other canals, by means whereof coals and metal are advantageously brought without any experience of land-carriage, and good conveyed to all parts of the kingdom. – For further particulars apply to Mr John Whitehead at the Green Dragon, in Jersey Street, near Ancoats Lane; or to Mr James Taylor, Attorney, in Exchange Street, Manchester.’

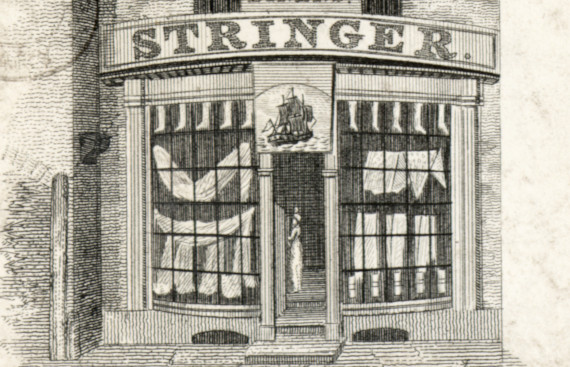

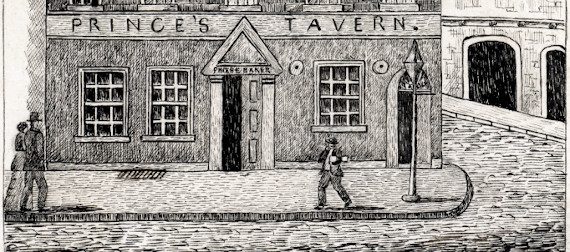

141 : Ship and Waterloo House

Another very attractive little engraving for business, from a firm whose name we have already seen in truncated form at number 129, Lockett Garnet & Co., Apple Market. The Apple Market occupied the space between the North Side of the Cathedral and the South Gate of Chetham’s, currently a pedestrianised area that is earmarked for development as the ‘Glade of Light’, a commemorative garden for the victims of the Arena bombing. The original is only a few centimetres across, and is full of detail such as the full-rigged ship and the fashionable lady customer glimpsed through the doorway. Linen from Ireland (and from domestic production of flax in Lancashire and Cumbria) had played a signficant part in Manchester’s early dominance of the regional cloth trade. We’re able to read and write this because of the money made by our founder Humphrey Chetham in the trade in fustians, typically woven from linen thread and wool crossing each other in the handloom industry of the region, and he was by no means the only Manchester person to make his money buying and selling such cloth. By the time of this fine little advertisement (we’re probably not so very far on from Waterloo itself in 1815), Irish linen may well mean finished cloth imported from Ireland, and the ship certainly suggests the Irish sea as the source of the shop’s stock-in-trade. As Manchester itself became the world centre for the cotton trade, the money made could suck in luxury goods for the newly wealthy, including the renowned Irish products.

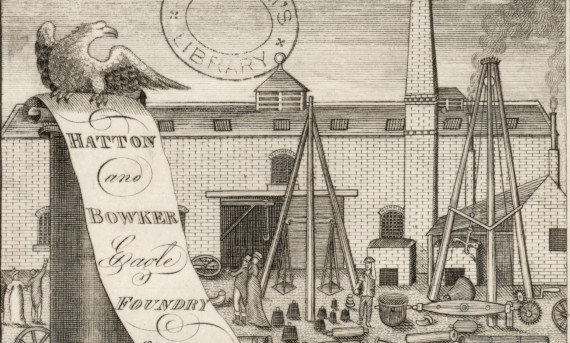

140 : Hatton & Bowker, Eagle Foundry

The Scrapbook’s tour of trade cards and bill-heads continues with this crowded little image of Hatton and Bowker’s crowded yard, packing in all the variety of castings and iron products that the Georgian town needed, from the industrial in the shape of pipework, weights, hand and tramway carts, gear-wheels and rollers, to the domestic in the shape of railings, gates and fire-grates. We think of the cotton industry first and foremost in Manchester’s catchment area as a centre for trade; to provide the machinery of all kinds that went into the increasingly large, more frequently steam-driven mills took a vast secondary ancillary effort, with machine makers springing up to supply the factory masters’ needs. As the excellent Grace’s Guide reminds us: ‘Bancks’s 1800 directory for Manchester and Salford lists, for example, nearly forty makers of machines (textile machines), and 16 iron foundries.’ Many of these concerns, such as Oldham’s Platt Brothers, became international exporters of textile machinery and outgrew the industry they were formed to serve. By 1849, the foundry appears on the Ordnance Survey map occupying a site between Booth Street and Clowes Street on the Salford side of the Irwell, near Blackfriars Bridge, By 1870, the Eagle Foundry name had passed to John Fletcher and Son, who exhibited an prodigiously large mill pulley in 1876. The commercial artist who added not only a worker, but two smartly dressed couples apparently admiring the output of the foundry did not forget to advertise himself: ‘Drawn and Engrav’d by Rd. Alsope, Manchr.’ There was a Richard Alsope, son of William and Susanna, born in 1845 and baptised at the Collegiate Church, but the style of the engraving here, with its First Empire costumes, flowing scripts and overall presentation is clearly too early in date to be his work. Was he part of a family tradition, and the heir in trade of an older Richard?

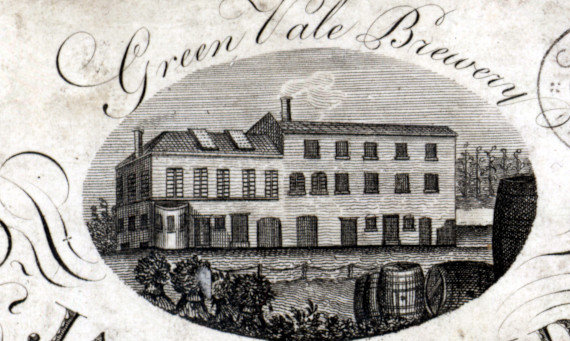

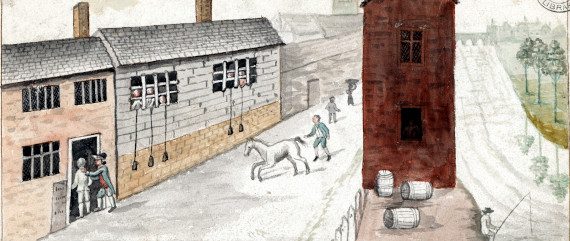

139 : Green Vale Brewery

As we have noted in looking at Mottram’s Brewery at number 135, Mancunians and Salfordians alike are noted for their abstemiousness and stern sobriety. We can see from the Green Vale Brewery, however, that more than one brewery survived in the town, no doubt selling their product to less scrupulous places. James and Samuel Wild evidently ran the establishment out of Salford, but we have not been able to locate it on any of the maps that seem to match the date. Is Green Vale related to Green Gate? The brewery must certainly have had a copious source of water, so were its wells close to the river? From the scene, perhaps a little idealised, in the engraving, we can find little to locate it, although the barley stooks and barrels – and are those hops rising high in the background? – complete the idea of the brewer’s stock-in-trade.

138 : Long, Hunting and Military Saddler

Today’s beautiful little trade card from Long’s the saddler is strongly reminiscent of the sort of work we saw in Sudlow’s engravers advertisement in number 137. It might almost have been made by them, but there is a minute signature, that of Pigot, who was a maker of maps and an issuer of early trade directories that are often used by historians of Manchester and region. There is a splendidly equipped cavalryman at the gallop, looking extremely gallant, and the proud boast of Mr Long that he is ‘Sergeant Saddler to the Manchr. & Salford Yeomanry Cavalry’, before moving on to less martial products such as luggage. We have already seen the prominent citizens of the town getting involved as colonels and officers of the home-service yeomanry units during the Napoleonic wars (e.g. nos 123 & 126), often re-establishing their volunteer units only a short time after their first disbandment following the short peace prior to 1803. The story becomes a little less dashing when we note the date added in manuscript to the card, September 1818. The Manchester and Salford Yeomanry Cavalry had been formed the year before, in 1817, not to provide backing for regular troops involved in war overseas with other states, but because of fears among Manchester’s administration of radical politics. It is hard for us to see the point of view of the Boroughreeve, magistrates and the ever-unpopular Constable Joseph Nadin; we find it difficult to imagine asking for a vote as dangerous sedition, even treason. It was the Yeomanry, local middle-class and landowning sons who could afford a horse and the uniform but who lacked real experience, who waded in the next August at Peterloo, and whose violent reaction sucked regular units into the square, creating further casualties. The magistrates who sent them in were thanked by the Crown, but as the facts became known their names and that of the Yeomanry became bywords for brutal repression, and the unit was disbanded in 1824. We have to wonder if Mr Long ended by wishing he had backed another horse.

137 : Sudlow, Engraver and Printer

As befits a professional engraver, Sudlow’s trade card is a particularly attractively produced advertisement. Engraving overtook all other techniques to provide fine quality pictorial and illustrative matter over the course of the eighteenth century, and while this card is undated the first empire costume of the female figure and style in general puts it comfortably in the Regency and Georgian era in which we have been immersed through most of the Scrapbook’s contents. Engravers undertook a wide range of illustrative matter, largely scoring their work into copper plates for printing in a specialised engraving press, altough using other techniques too. Sudlow’s own list exemplifies: ‘Wood cuts, Aquatints, Maps, Charts, Bills of Parcels, Address Cards, Pattern Card Papers, Gold and Silver Ornamental Stars, Labels, &c, &c, neatly executed.’ The scripts in which the card is written are in themselves and advertisement for the variety of styles available to the customer. Letterpress, printing from moveable metal types, dominated books and newspapers, and a wide range of fonts was available to the better-off printer; but if flowing script or decorative effects were wanted, and for the reproduction of any free-hand art work, the engraver dominated entirely. For each grand commission such as reproducing classical art or portraits of the great and good, a hundred ‘jobbing’ commissions would come up, such as the heads of bills we have seen in the last few examples.

136 : W.W. Paul’s paper-hanging warehouse

From the item itself we learn that the subject of this engraving was at 4, Oldham Street, and so close to the Infirmary Pond and to modern Piccadilly. Another bill-head is certain to have been the source, and again we can lament the excision of the rest, which might have given us some useful historical evidence. The word ‘warehouse’ here again is used to mean what we might call a showroom rather than a mere store; wallpaper, originating like so much else to do with paper in China, was known in England by the early sixteenth century, but began to be a mark of the urban sophisticate in the eighteenth. Papers were expensive, hand-coloured or hand-finished from block printing until roller printing began to offer economies in the 1830s, and the paper hanger might also be called on to hang such ultra-luxury materials as embossed leather and hand-painted silk. Floral elements or the fashionable Chinoiserie made up the styles. We should think of Paul’s elegantly pedimented warehouse less as B&Q, and more as a magnet for those wanting to express often new-found wealth from industry in the latest Metropolitan styles (W.W. Paul’s ‘newest patterns’); another way into the upper echelons of society. The appetite for this kind of display and luxury was such that the government guessed people would pay tax on top of the price in order to have their rooms done in style: a tax of a penny a yard was levied in 1712, rising to a penny halfpenny in 1714 and penny three farthings in 1777.

135 : S & I Mottram, Beer and Porter Brewers, Salford

The citizens of Manchester and Salford are known around the world for their distaste for beer in all its forms, and indeed for the prevalence of the most strict teetotalism. However, some small quantities of beer are occasionally brewed for visitors or invalids and the Mottrams seem to have filled a part of this requirement from their Bury Street premises. We apologise for the hard-to-read nature of this image; the item in the Scrapbook is taken from the engraved plate of a business card, but is a peculiarly weak impression and the enhancement here is the best we could achieve. The brewery was certainly active by 1831, when a terrible accident occurred, leading to the loss of much precious stock, and the drunkenness of a pig. Two excellent beer-related sources, Zythophile and the Brewery History wiki record the terror and porcine shame in a quotation from the Chester Courant of 1831 :

“A Flood of Porter. – On Wednesday morning a large porter vat, containing about 380 barrels of the best brown stout, burst on the premises of Messrs. Mottram, in Brewery-street, Salford (Manchester.) The liquid rushed out with such force as to carry before it a portion of a wall, under which it nearly buried a man and horse, which were at the outside. Another man, who was in the same room in which the vat stood, was carried out into the yard by the flood. The beer overflowed a pond, and was for a few minutes two feet deep in the cellar of a cottage. All sorts of vessels were in requisition for carrying off the precious liquid from the pond. Among other comers was a sow, which was seen in the course of the day staggering off in a state of disgusting inebriety. The loss from the accident, we regret to state, is estimated at from £700 to £1000.”

Mottram’s was bought up by the Cornbrook Brewery in 1897.

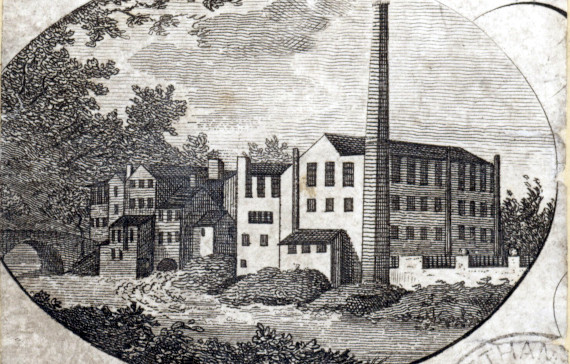

134 : Ancoats Paper Mill

From the remains of the swash lettering to the right of this tiny image, we can be sure it’s another piece cut from a bill-head. The mill is – not unexpectedly for an industry requiring a copious water supply – evidently on river next to what appears to be a public bridge over that river. There is evidence for a Medlock Paper Mill, but this operated from near Buxton Street and thus near the Ardwick bridge over the Medlock, too far off to have been known as Ancoats Paper Mill. The excellent Grace’s Guide finds a 1788 reference to ‘Bracken and Meredith, paper makers, Hanging Ditch and Ancoats Bridge’, suggesting offices and warehouse at Hanging Ditch and a works next to the Ancoats bridge over the Irwell, near the present Pin Mill Brow. The engraving certainly looks Georgian rather than later. James Meredith (who was also a pin maker in 1788) appears again in Bancks’ 1800 directory as ‘pin and paper manufacturer, Ardwick Island, warehouse 12 Hanging Ditch.’ After the coming of the railways, culverting of the Medlock and a hugely expanded road network, a good deal of imagination would be needed to recreate the Ancoats Paper Mill to those standing on the inner ring road today.

133 : Salford Iron Warehouse

Another small engraving from a bill-head, the snippet it is on measuring 93x63mm and packing in a surpising amount of detail. We’re not reduced to speculation or second-hand evidence for this one, however, as we’ll be seeing a bill-head at number 147 that has mercifully left the lettering for us too. We thus know that this is from the iron warehouse of William Hatton of 22 Chapel Street, Salford, ‘Manufacturer and Wholesale Dealer in Nails, Tin’d [i.e galvanised], Iron & Copper Hooks …’. There’s more, but we’ll revisit that when we get to the more complete item. When we do, it will be seen that this engraving, while it seems certain it’s from the same plate, is in an earlier state than is number 147, lacking a couple of details. These bill-head engravings, smaller, more modest and less picturesque than the bulk of deliberately nostalgic and backward-looking images of ‘Old Manchester’ are the truth, and a depiction of the smoke-stack prosperity, of the early nineteenth-century town as it headed towards city status in the charter of 1852.

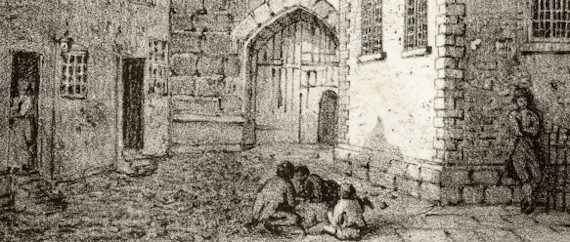

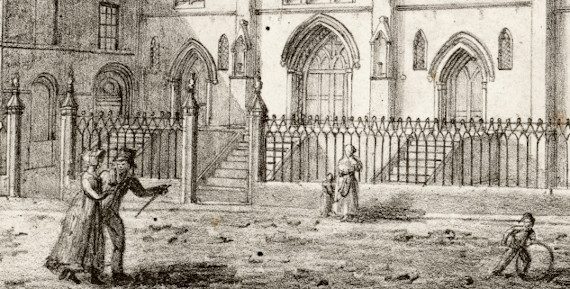

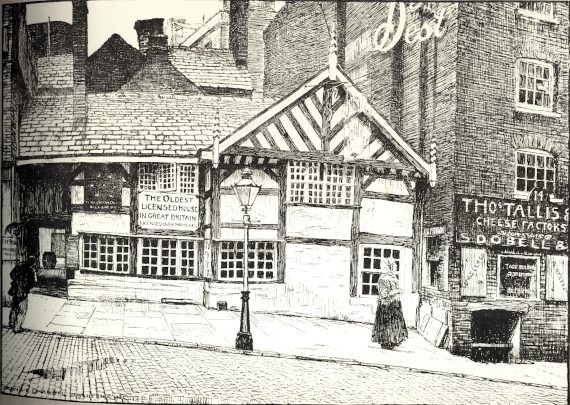

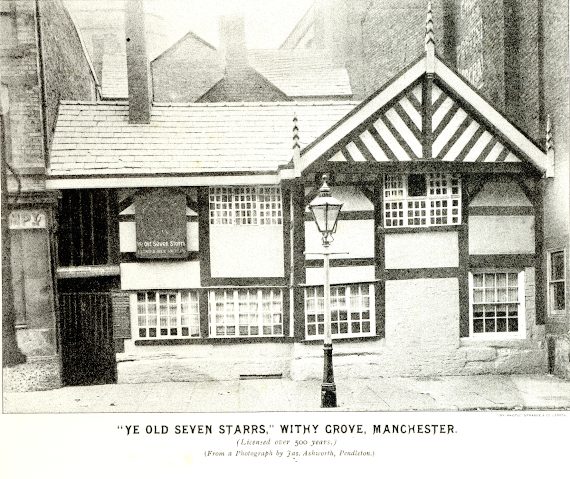

132 : Poets’ Corner

Poets’ Corner, the meeting place for a loose group of writers and poets in the 1840s, was on the premises of the Sun Inn on Manchester’s Long Millgate. The corner of the street to the left is opposite the main gate of Chetham’s on today’s truncated, pedestrianised Long Millgate, and the Sun Inn was opposite the present 1860s Manchester Grammar School extension on what is now the grassed area behind the Football Museum. Long Millgate, a somewhat run-down street the importance of which as a thoroughfare to points north was destroyed by the construction of Corporation Street later in the nineteenth century, retained a number of picturesque timber-framed buildings, and the Sun Inn in particular was a frequent subject for artists and photographers. The poets and writers appear not to have gathered here over a long period, but the name lived on and no doubt suited the licensee in attracting customers. The Library holds a poetry manuscript by one of the more interesting poets, Robert Rose, and you can read about him and his untimely death in a piece on our blog by the late Michael Powell.

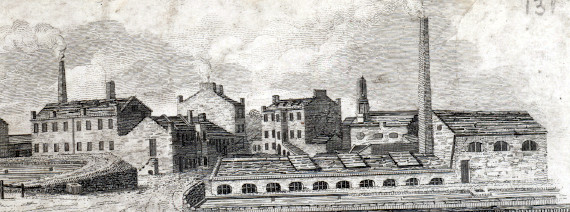

131 : Mills

Students of this page may have noticed ungrateful and grumpy remarks from us as editors about the typescript handlist that provides a portion of the basic information about the contents of the Scrapbook. In this case it limits its description to the less-than-detailed ‘Factory [Unknown]’. The image is 130×80 mm, and coming among others cut from the heads of bills and receipts we might speculate that this comes from a similar source. A detailed image with what may well be spinning and weaving sheds, and two steam engines to feed those tall stacks, we’re again looking at a definitively early nineteenth-century scene from the cloth industry, viewed across a canal cutting, and then rather disarmingly also viewed across what seems a neat little domestic garden with flower beds and a sundial, as from the window of a house. It’s three o’clock according to the clock-tower in the middle distance, so a good while before what was probably a twelve hour shift finishes. We’d be delighted to receive suggestions as to the identity of the mills or the location of the scene.

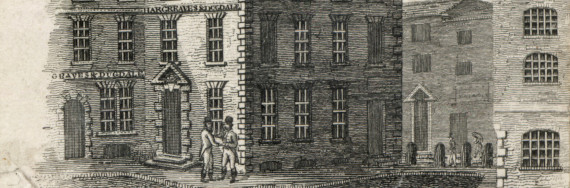

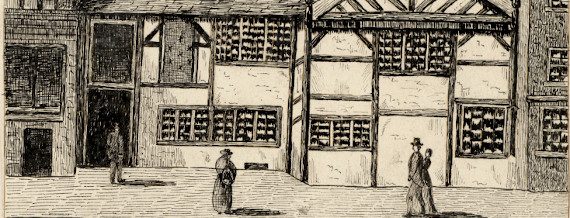

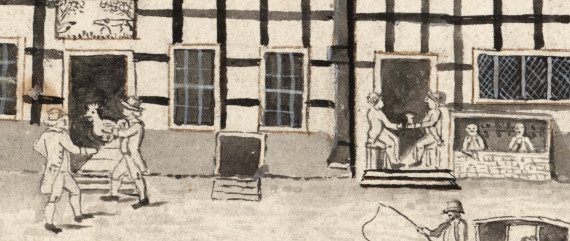

129 : Dugdale and Hargreaves warehouse

A mountainous bit of paperwork has rather broken the every weekday rhythm of these posts, but we’re back with another image excised (as we learn from the typescript index to the Manchester Scrapbook) from a bill-head, and again we might rather regret the absence of the rest of the bill; however, we have to thank those who assembled the Scrapbook for the survival of any of these extreme rarities at all. This is the warehouse of Hargreaves and Dugdale, in Marsden Square off Market Street. It would now be under the Arndale. Hargreaves and Dugdale were calico printers, making the patterned cotton cloth for which Manchester was famous world-wide. They began trading in 1818, and the name continued as a going concern until 1922. We can be confident that the hand-shaking figures on the pavement are Hargreaves and Dugdale themselves. Their understanding of ‘warehouse’, like that of their fellow Mancunian manufacturers, was not the modern one of large-scale storage and distribution away from the public eye, but an attractive sales floor to show off the products to buyers; the Britannia Hotel, for example, with its remarkable staircases, was originally a warehouse in this sense. We’re lucky that our friends at Manchester Local Studies and Archives have papers – and more excitingly swatches and pattern books – for this long-lived concern. Thomas Hargreaves and Adam Dugdale became partners in running the Broad Oak printworks (cotton rather than books, of course) in Accrington in 1812; but Manchester was the place to sell. Down at bottom right is a truncated signature, ‘Lockett Garn …’, sliced through by the person making the cutting; a complete form survives in number 141 above.

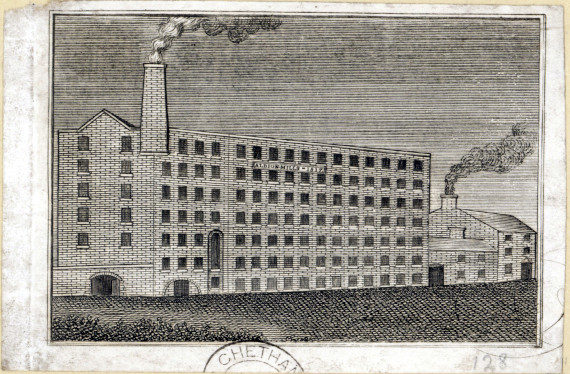

128 : Albion Mills, 1817

Another bill-head furnishes this small image of Albion Mills, proudly bearing its name and dated 1817. The word ‘iconic’ is bandied about to the extent it has come to mean little, but perhaps we could wheel it out again to suggest that this image encapsulates what everyone imagines when the phrase nineteenth-century Manchester is used. William Blake might have drawn it in a less pedestrian fashion, but surely this is the epitome of the dark, satanic mill of imagination, slab-sided and billowing smoke. There seem to have been more than one Albion Mills, Albion Works, or Albion Bridge Mills, but perhaps this is the successor building to that Albion Cotton Mills noted under 1816 in Axon’s Annals: ‘The Albion Cotton Mills, situated in Great Bridgewater Street, were burned down, December. Damage, £25,000.’ Do you know differently? Please let us know if so.

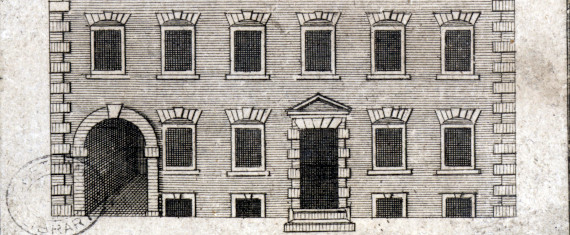

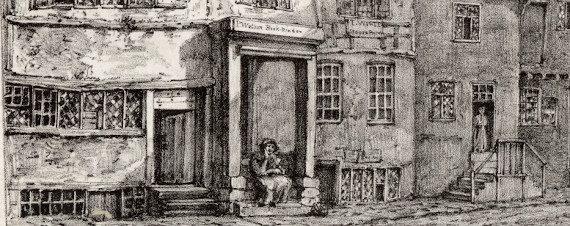

127 : Warrington’s Shop

Whereas some of the former pictures contain enough information in their captions to bring out some historical detail, this small image, pasted in at no. 127 in the Scrapbook, has no script with it at all. ‘Warrington’s Shop’ comes from the cursory and less-than-attractive typescript index made sometime in the twentieth century, and offers few clues. The shop is evidently a well set up place, with pedimented door, elaborate display windows and three further storeys of sash-windowed accommodation above. The handlist also dates the image ‘Temp. Queen Anne’ (i.e. 1702-14), and tells us it is an engraving cut from a bill-head. We regret now that the whole bill head was not kept, as it would probably have given us the business of the shop and some other clues. The date is too early for the shop to have an entry in any of the town’s early directories – Elizabeth Raffald produced the first in 1772 – but we’ll try to fill in more detail once we’re back in the Library if there’s anything to be found.

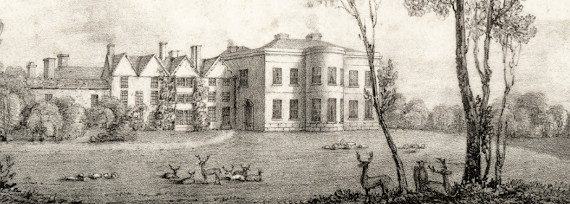

126 : Lark Hill near Manchester seat of Col. Ackers

After yesterday’s Bank House, we’re staying with the influential Ackers family with this image of their house at Lark Hill, a site now occupied by our friends at Salford Museum and Art Gallery, overlooking the bow of the Irwell and Peel Park. The image is again one of the tiny engravings cut from an unidentified diary, in this case intended to embellish December 1805. Again the Ackers involvement in Bank Mill, in which Colonel James Ackers became a partner in 1793, means the money from the mill was still being spent locally in the shape of a grand mill-master’s house. James was Boroughreeve of Manchester (the nearest thing to Mayor in the unincorporated town) in 1792/3. He was Colonel to a regiment of Manchester and Salford Volunteers who were presented with their colours in 1798, and was repaid in 1799 by their gift to him of a large silver vase and set of goblets. In 1800, he was appointed High Sheriff and his volunteers formed an escorting troop for a procession by way of celebration. The same pattern affected his wartime volunteer regiment as we saw in numbers 122 and 123; like Ford’s and Wiltons’ troops, they were disbanded after a short-lived peace with France in 1802, but 1803 saw James Ackers raising another regiment with the rather more proprietary name of ‘Ackers’s Volunteers’. They boasted 1,017 men by 1804. He died in 1827 at the age of 71. The idea of a ‘seat’ in this series of small images takes the wealthy manufacturer further towards the coveted status of the great landed family, with distant but complimentary echoes of coming over with the conqueror; the Napoleonic emergencies gave them further opportunities to be involved in the equally socially useful matter of becoming colonels of regiments. Local volunteers they may have been, but nonetheless it was a step well away from the factory and towards the glamour of Horse Guards – until Peterloo rather took the shine off in 1819.

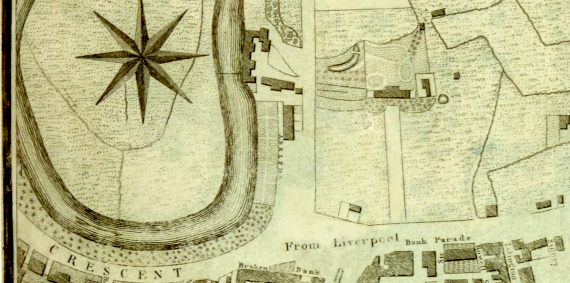

125 : Bank House near Manchester seat of H.Ackers Esqr.

For July 1805 in our unidentified source, we come to a good example of the emergence of the manufacturer into landed society, a phenomenon with which Georgian Manchester was becoming very familiar. Holland Ackers had died in 1801, but he and his brother James had by 1793 already used their Bolton fustian manufacturer father’s fortune to buy Great Moreton Hall in Cheshire, together with its estate, for £57,107 – a king’s ransom. Great Moreton Hall was rebuilt to reflect the family’s ambition to enter the ‘old money’ squirearchy, replacing the timber house that successions of Bellot family baronets had been content with. Bank House was simply not grand enough. Holland Ackers had been instrumental in founding Bank Mill in 1782 on the loop of the Irwell by the Crescent, and Bank House was nearby. The pattern of later generations taking up residence in high country style well away from their father’s and grandfather’s mill-owners house close to the mill gates was to be followed across Lancashire and Yorkshire as industrial fortunes were made and spent.

Bank Mill and House on the Irwell near Salford Crescent, still semi-rural in 1809

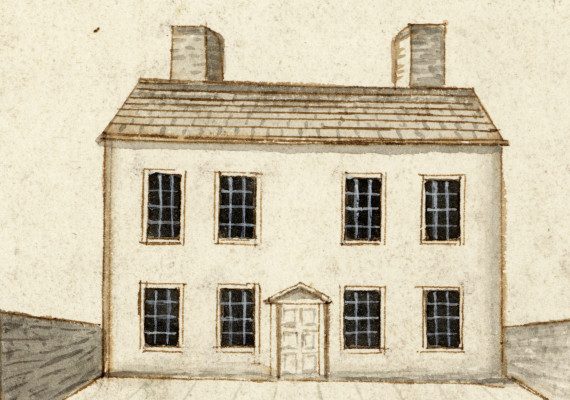

124 : Hart Hill near Manchester, seat of Jno. Simpson Esqr.

Another snipping from the unknown diary that furnished the Scrapbook with the last few images, this one is dated 1805. Hart Hill is now an area of Buile Hill Park, Salford, and not far from the site of number 122, Claremont House. John Simpson was tenant or proprietor of what may have been the second house on the site, depicted here, which was itself replaced by new owner James Dugdale to a design of 1859 by architect Walter Scott. The land was acquired by Salford Corporation for housing and then to extend the public park, and Dugdale’s mansion demolished in 1926. We’re inebted to the excellent page on Hart Hill on the Eccles Old Road website; from its section on the houses at Hart Hill, it appears this may be the only image of the eighteenth-century house. We’ll confer with the editors and see what they think.

123 : Heaton Hall, seat of Ld. Wilton near Manchester

Another of the attractive but tiny images from an unidentified 1804 diary, this one rather torn. Heaton Hall, now at the centre of the Manchester area’s largest park. Lord Wilton, or to give him his full name and titles at this date, Thomas Grey Egerton, 1st Earl of Wilton (1749 –1814) was, like John Ford, a Colonel of a volunteer regiment, and by 1803 had raised the Heaton Volunteer Artillery. These were semi-private home-service only units, intended to free up more regular formations for overseas service. The Hall itself was rebuilt by Thomas Egerton to designs by architect James Wyatt (1746–1813), then among the best known in England for his neo-classical and (later) neo-Gothic style.

122 : Claremont near Manchester, seat of Col. Ford

By the time this image of Claremont House was used for the diary in 1804, Colonel John Ford, descendant of a Staffordshire family, had disbanded his Manchester and Salford Volunteer Light Horse in 1802 during the brief peace with France (its colours being deposited at his house), and gone on to become Lt.Col of a Cheshire volunteer regiment in 1803. He had Claremont House built as his country residence, and had a house in King Street Manchester. He had studied at Manchester Grammar School, then next door to Chetham’s, an institution of which he later became a feoffee (governor of the charity). He died near Sandbach, Cheshire in 1839. As with the rest of the diary illustrations surviving in the Scrapbook, the pictures are evidently intended to draw the mind of the user towards the grandeur in which such men lived, perhaps to encourage aspiration and achievement. We’re grateful to MMU’s Tom McGrath (Twitter @TomMcGrath_) for the following information on where Claremont House was, and what’s now occupying its former space. The Heywoods are, of course, another and a very important Manchester story:

‘Claremont was located in Pendleton, not too far from Buile Hill. After the death of Mrs Ford in 1825 it was occupied by Benjamin Heywood & the Heywoods stayed there until it was demolished in 1924. Buckland Road now covers the site of the hall.’ If you’re finding this page interesting, don’t miss Tom’s fascinating site at www.ifthosewallscouldtalk.wordpress.com. Thanks, too, to Instagram user Redminimadness, who adds: ‘Claremont House was in Salford just off Eccles Old Road. Nearby were Hope Hall, Hart Hill Buile Hill Hall which were residences of other notable people from Manchester and Salford. The only building that still exists from the estate is Claremont Lodge.’ Both your contributions much appreciated.

121 : Trafford Hall

The next few images of some of the Manchester area’s grand houses come, according to the dismal typescript index to the Scrapbook, ‘from a diary’, and indeed they each provide the image for a month in 1804. It would be interesting, but no doubt pretty hard, to find a complete copy. It seems likely to have been a small publication, as each of these images is only about six by three-and-a-half centimetres. The first is this view of Trafford Hall, a grand house eventually surrounded by the burgeoning industrial development of its own park, ‘Trafford Park’ probably meaning gentile grandeur and deer to the artist responsible here, and gigantic manufacturing facilities by the time the hall itself was demolished in 1939. The park in former days was the subject of one of the James series of engravings, with Mrs Pettiward (nee Jane Seymour Colman) sister-in-law and co-heiress of Sir Thomas Joseph de Trafford (1778-1852) as guest artist for the original drawing. We have seen this already in the Scrapbook at number 76.

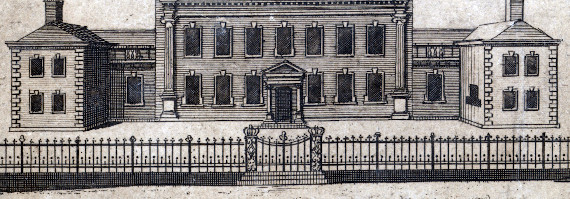

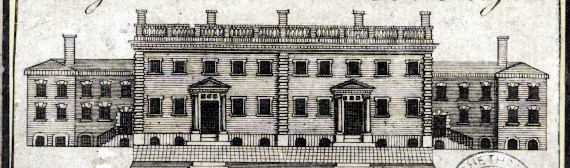

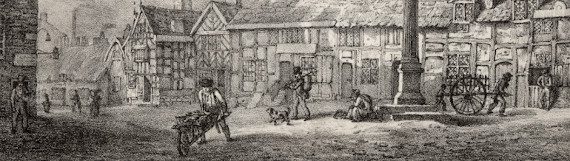

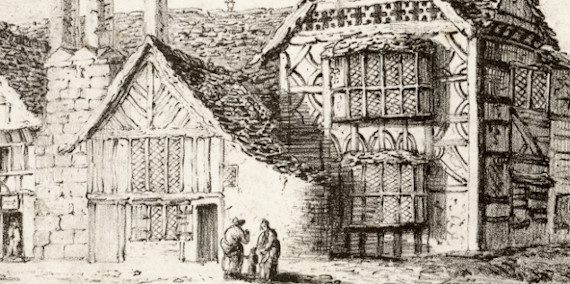

120 : Mess. Clowes’s House at Huntsbank

The last of the border images from the Casson and Berry plan in the Scrapbook, Messrs. Clowes’ house is perhaps the most magnificent of those portrayed, or at least seems set in the largest plot, with eagles on the gates, paired front doors and impressive wings. Huntsbank, or Hunts Bank, is a name that has shifted meaning over time, now being used to refer to the slope upward towards Victoria Station, a slope built up artificially by the construction of the railway. On the plan, it refers to a street running roughly where Victoria Street now sits on its 19th-century artificial river bank, north away from the west door of the Collegiate Church to the small bridge over the Irk. The plan does not mark the house either in its indexing system, nor on the mapping. It is now hard to imagine where it could have stood, later plans and maps giving little help. The Clowes name is associated with many prominent Mancunians, fellows of the Collegiate Church, landowners, and as we saw in number 77, owners of Broughton Hall.

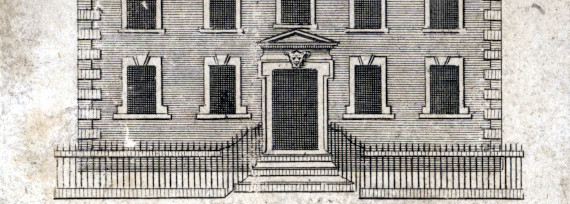

119 : Mr Touchet’s House in Deansgate

The penultimate in the Scrapbook’s series of cuttings from the border of the 1740s Casson and Berry Plan of Manchester and Salford. The Touchet house, looking perhaps as if it might owe a little to what the age called a warehouse as well as a large residence, was the abode of Thomas Touchet, a pinmaker from Warrington, who, like Humphrey Chetham before him, dealt in fustians and also in cotton cloth. He died leaving a fortune in 1744. The house is remembered again by Harrison Ainsworth in his nostalgic tour of the Manchester of his early memory in the preface to The Good Old Times (1873), recalling how the views in the plan helped him write: ‘Views are given in this plan of the principal houses then recently erected, and as these houses were occupied by Prince Charles and the Highland chiefs during their stay in Manchester, I could conduct the rebel leaders to their quarters without difficulty. One of the houses, situate in Deansgate, belonged to my mother’s uncle, Mr Touchet.’

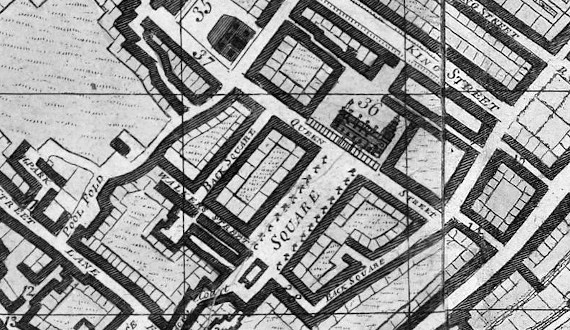

Like the quay (number 114) before it, the image of St Ann’s Square in the border of the Casson and Berry plan is one of a few that are not solely of the private house of a wealthy resident. The decorative items in the border of the plan also surround the text that acts as a description, if not an advertisement, for the growing town, and there is clear pride – perhaps low church partisanship? – in St Ann’s: ‘A new Parish has been erected & a large Sumptuous Church therein built, call’d St Ann’s …’ As will be seen from the detail below, St Ann’s square perhaps looks closer to unchanged than almost any other feature of the 1740s mapping. It will also be seen that the ‘Dissenters Meeting House’, known to us now as Cross St Chapel, is very close at hand. A clue to this closeness and the name of the church is that Lady Ann Mosley, who had hitherto lent her support (in defiance of her thuggish husband) to the newly tolerated dissenting chapel on what is now Cross Street, returned to the Anglican communion, but as a member of the “low church party”, puritan in outlook, opposed to ritual, Hanoverian in politics. The only church in Manchester, the Collegiate Church of the single large parish, was distinctly High Church and leant towards the Jacobite cause. Ann’s new parish and Church of St. Ann’s was consecrated in 1712, only three years before the 1715 Jacobite rising and at a time of high tension within the Church of England and Britain as a whole. There is a good article on the history of the Cross St Chapel by Geoffrey Head that tells a fuller tale. The manuscript diary of Henry Newcome, the dissenting minister who can be regarded as the founder of the Chapel, is among the diaries at Chetham’s Library.

Detail of St Ann’s Square from the Casson & Berry plan, the church itself at 36, close by ‘Meeting House Walk’ (37) and the ‘Dissenters Meeting House’ (35).

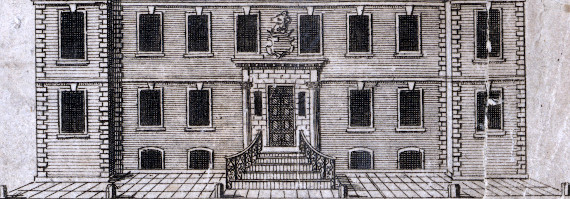

117 : Mr Croxton’s House in King Street

The Casson and Berry plan border continues its tour of prominent houses with Mr Croxton’s; in this case we do have another view of the same house seventy or so years later, in the shape of Ralston and Aglio’s view of the ‘Late Dr White’s House on King Street’ at number 99. In Ralston’s drawing we can see how the house stood well above the roadway, with a separate elevated pavement to its front, apparently public by the 1820s at least. James Croston, who published a reprint of the ‘Views’ in 1875, provides a narrative that again takes us back to the 1745 rising: ‘A view of the house in King-street is given in Casson and Berrey’s maps of the town in 1746, 1751, and 1755, and it is there named as Mr. Croxton’s. Mr. George Croxton was an opulent merchant of Manchester; in 1743 he purchased the estate of Birch Hall, in Rusholme, from Humphrey Birch, a grandson of the famous parliamentary commander Colonel Birch, a property he sold two years later to Mr. John Dickinson, of Market-street-lane, who in the same year lodged Charles Edward Stuart during his stay in Manchester.’

116 : Mr. Marsden’s House in Market Street Lane

Our walk round the border of Casson and Berry’s 1740s plan of Manchester and Salford brings us to another long-vanished grand eighteenth-century house. This house again makes its way, via the plan, into Ainsworth’s The Good Old Times, set in his fictionalised account of the 1745 Jacobite rising, and is described as ‘a fine house in Market Street Lane, occupied by Mr Marsden’ which Ainsworth has ‘allotted to the Marquis of Tullibardine and Lord Nairne.’ Again the Plan does not locate the house for us on Market Street, but the presence of Marsden’s Square just to the west of the High Street and connected by a short street to Market Street itself may be a clue. Despite its very characteristic appearance, size and splendour, its cupola and its distinction in being set back from the street, it appears nowhere in the Georgian views of Market Street that we reviewed below.

115 : Mr Hawarth’s House in Millgate

The border of the Casson and Berry plan of the 1740s again provides today’s image. Mr Hawarth’s house doesn’t figure on the plan itself, but Millgate, the remnants of which are now the discontinuous and pedestrianised Long Millgate (address of a Library you may have heard of) was a much larger thoroughfare, running past the East end of the Collegiate Church and swinging eastward to reflect the course of the River Irk as it debouched into the Irwell. The driving through of Corporation Street, and even more so the construction of the railways with their bridges, viaducts, embankments and buildings completely altered the lie of the land and the visibility of the Irk, and more or less obliterated the eighteenth-century appearance of the area. Even before the Irk was hidden below the Edwardian extension fo Victoria Station, Richard Procter’s Memorials of Manchester Streets (1874) quoted a Manchester Guardian article of ten years before: ‘To citizens familiar with the locality it scarcely need be told that, for most useful or ornamental purposes, this street – ruthlessly cut into many pieces – has been virtually dead several years, only requiring to be put decently out of sight.’ No house as grand as Mr Hawarth’s appears to have survived into the photographic era. The Hawarth (or on some spellings Haworth) family were (Procter again): ‘The last important family residing in Long Millgate’, their name being given to ‘Haworths’ Gates, a narrow passage which was stopped up by order of the City Council in September 1868′. The Hawarth who was flattered by this print of his residence would have been Abraham Haworth, who ‘died at his house in Milngate’ in 1759.

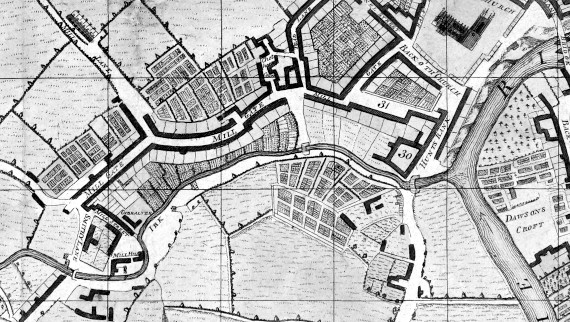

Millgate on the 1740s Casson and Berry plan. Chethams (30) and the Church are about the only structures remaining, and the Irk is now hard to find.

114 : The Key

‘The Key’ in the caption, or ‘The Kay’ in its place on the main portion of the Casson and Berry plan, lay at the foot of ‘Kay Street’, our own Quay Street, and as the snippet from the plan below shows us, was several fields away down what was still effectively a country lane in the 1740s. Manchester would continue to develop its water-borne transport links in the shape of a complex system of canals and canalised river-ways, culminating in the Port of Manchester and the Ship Canal. But the quay was already seen as an important aspect of the commercial life of the town when this view was cut. The plan of Manchester offers a description of the towns of Manchester and Salford as well as the main map and illustrations, and says of the Quay: ‘The River Irwell which Washes a great part of ye Town is now made Navigable & a handsom Key is created for unloading &c. … There is not any Town in the Nation excepting our Sea Ports that may be compar’d to it in Trade, as appears from the number of Packs or Goods which go weekly out of the Town.’

‘The Kay’ on the Casson and Berry plan: the mid C18 town with its nascent port at some distance from the built up area down ‘Kay Street’

113 : Mr Dickenson’s House at top of Market-Street-Lane

The border of the Casson and Berry plan again provides our next scrapbook paste-in. As with yesterday’s view of Mr Johnson’s house, Mr Dickenson’s played a part in the Jacobite rising – in fact, the starring role of any building associated with Manchester’s most exciting year for a long time. As the Victoria County History tells us: ‘The whole force reached Manchester the following day, the prince himself riding in during the afternoon, when his father was proclaimed king as James III. Mr. Dickinson’s house in Market Street was chosen as head quarters and was afterwards known as ‘The Palace.’ At night many of the people illuminated their houses, bonfires were made, and the bells were rung. Some three hundred recruits had joined the invaders, and were called ‘The Manchester Regiment.” Its time as ‘The Palace’ was brief; and following defeat at Carlisle and Culloden, brutal justice had a brutal monument in the shapes of Jacobite heads on the Manchester Exchange. Like all the private buildings in the border, it was long gone by the time Harrison Ainsworth wrote his preface to The Good Old Times in 1873: ‘… gone, as is Mr Dickenson’s fine house in Market Street Lane, where the prince was lodged. Indeed, there is scarcely a house left in the town that has the slightest historical association belonging to it.’

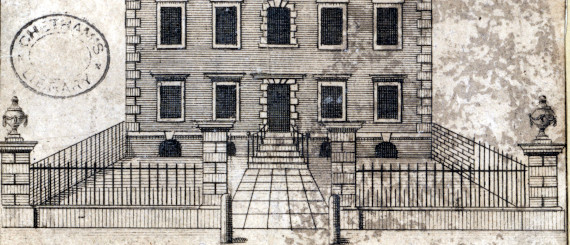

112 : Mr Johnson’s House

Our walk round the border decoration of Russel Casson and John Berry’s 1740s Plan of Manchester and Salford continues with another imposing gentry house. When we looked at number 108, another map-border image, we mentioned best selling Manchester Novelist William Harrison Ainsworth (1805-1882) and his romantic account of the 1745 Jacobite rising, The Good Old Times, and speculated about his using the near-contemporary plan for his narrative. A bit more reading this week in his preface makes it quite clear that he did exactly that: ‘When I was a boy some elderly personages with whom I was acquainted were kind enough to describe to me events connected with Prince Charles’s visit to Manchester … little of the old town, however is now left.’ In imagining the scene that greeted Bonnie Prince Charlie he ‘was saved from the possibility of error by an excellent plan, almost of the precise date, by John A. Berry, to which I made constant reference during my task. Views are given in this plan of the principal houses then recently erected, and as these houses were occupied by Prince Charles and the Highland chiefs during their stay in Manchester, I could conduct the rebel leaders to their quarters without difficulty.’ Ainsworth has Prince Charlie tell Lord Derwentwater to introduce him to another character as ‘Mr Johnson’ as an incognito – are we looking at the inspiration here?

Johnson’s house on High Street opposite Church Street in a detail from the Casson and Berry plan, with an inverted ’48’ above it referring to the plan’s key

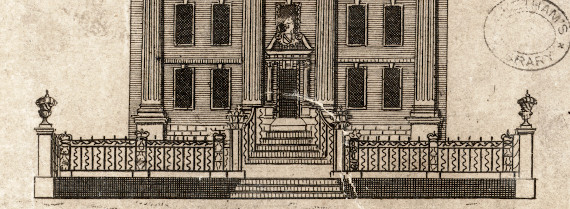

111 : Francis Reynolds Esqr. – Strangeways Hall

As we continue round the border of the 1740s Casson and Berry map, we cross the bridge over the Irk on the northern edge of eighteenth-century Manchester to arrive at Strangeways Hall. The Hall and its lands are said to have acquired their name through the Strangeways / de Strangeways family; given ‘de’ titles are usually indicative of people who acquired their name by being from a particular place, this argument may be a little circular. The hall was sited not far from the prison now known as HMP Manchester, renamed in some haste after a particularly egregious riot. The site is now completely unrecognisable, and major buildings have come and gone since the disappearance of the hall in 1858, when its final owner sold building, furnishings and site for demolition and clearance. The image here is perhaps the best known, reproduced and thus more widely seen in the form of a direct copy for Procter’s Memorials of Manchester Streets later in the nineteenth century. Francis Reynolds (d. 1773), was the owner at the time over which the various states and editions of the map were issued, was an MP for Lancaster (Manchester itself, of course, having none), and faced down a couple of challenges to his inheritance of the estate. There’s a good blog post about the Hall and its families of owners.

110 : Mr Marriotts House in Browns Street

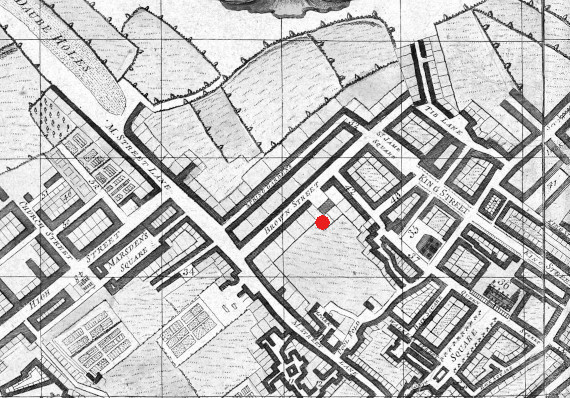

Another splendid house found depicted in the border of the Casson and Berry maps, this mansion was due to Joshua Marriott (b. 1719), a successful threadmaker who also became involved in finance. Below is an attempt to show (immediately above the red dot) what seems certain to have been the site of this house, set back from the rest of the buildings lining the street. The map uses bold black lines to indicate built-up sections of street. Marriott seems to have been a worshipper at St Ann’s Church, and an anti-Jacobite. There is an interesing attempt to GeoTag the exact location of the house on Flickr, and there is also a very interesting blog post about this house, the Marriotts and associated events and places.

A detail from the Casson & Berry map showing the likely location of Marriott’s house

109 : Messrs. Miles Bower and Son Houses

Miles Bower and son are recorded, among a long list of other names, as putting up a ‘loyal contribution’ to provide for forces to resist the advancing Jacobite army in 1745, in their case a relatively modest £20. Being on the winning Hanoverian side can have done them no harm at the date of the Casson and Berry maps, and certainly their house, on Deansgate, verges on the palatial. The family made their money in the felt hat trade, and Miles Bower junior and senior brought the business to the kind of success their mansion-like house depicts. Miles Bower senior died in 1780, at the age of 85; he and his son served on the court leet of Manchester and the firm features in Mrs Raffald’s Directory of Manchester – the first – in 1772. The hat works passed out of the hands of the Bowers, but was still making hats in 1849.

108 : Floyd’s House

Today’s image leaves the sophisticated work of Ralston and Aglio behind and moves on to what are effectively cuttings from the celebrated maps of Manchester made for and by Russel Casson and John Berry, A Plan of the Towns of Manchester and Salford in the County Palatine of Lancaster between 1741 and 1757. The Library has several copies of this map from different dates; the survey, such as it was, doesn’t change from issue to issue, though the borders, including these images of notable buildings, do change. Manchester’s most successful nineteenth-century novelist, William Harrison Ainsworth, brings this house into his novelisation of the 1745 rising, The Good Old Times, as Bonnie Prince Charlie’s lieutenants search the town of Manchester for a suitable royal headquarters: ‘Mr Floyd’s house, near St Ann’s Square, was next visited; a handsome mansion, ornamented with pilasters, having a Belvidere on the summit, and approached by a noble flight of steps …’. They reject Floyd’s house, but as they continue round the town the names of the houses considered coincide exactly with the grander houses on the margins of the Casson and Berry map. As a frequent reader at Chetham’s, it may well even have been one of our copies of the map from which he picked names and descriptions. Ainsworth always took full advantage of the novelist’s freedom to create a pleasing narrative, so we need not necessarily see historical detail in his account. There’s a little more on this famous map in one of our ‘101 treasures’ posts, and we’ll consider it more in the next few days.

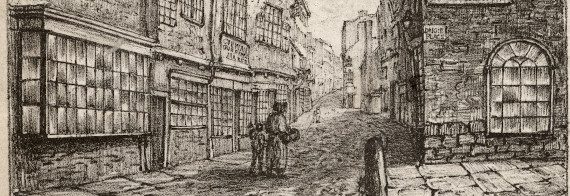

107 : Middle Market Street, Manchester

A final view of Market Street from the ‘Views’ series that we started to look at with its title page at number 98. We’ve come back down the hill a little, though there aren’t enough landmarks to say exactly where. Was the demolition on the right anything to do with the street-widening programme the Act commemorated put in train? Again, it’s credited ‘From Nature by Ralston, & on Stone by A. Aglio’, printed by Aglio, who this time gives his address, 36 Newman Street. As we’ve observed, these are local views but not local productions; the Newman Street concerned was off Oxford Street, London, not Manchester.

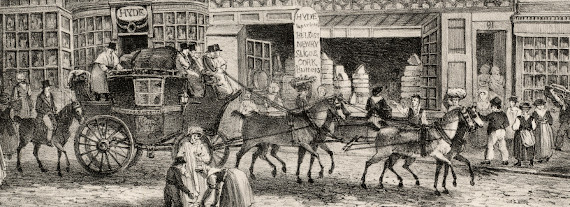

106 : Top of Market Street, Manchester

‘From Nature by Ralston, & on Stone by A. Aglio’, and printed again by Aglio himself. This is not, perhaps, what you and I might think of as the top of Market Street, Brown Street to the right here being little more than half way between Market Place and Piccadilly, downhill from Spring Gardens. It looks towards Piccadilly, but we can only guess at where High Street might cross, and we’re quite out of sight of things like the Infirmary pond. The scence fairly bustles, though, and you can get your ticket to London on the coach, buy luggage to take with you and stock up on snuff for the journey all without leaving the frame of the print.

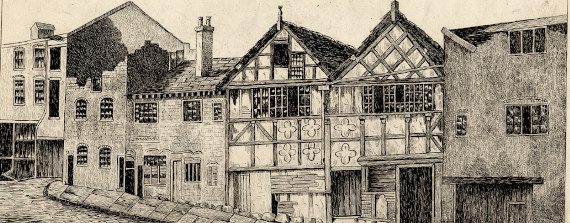

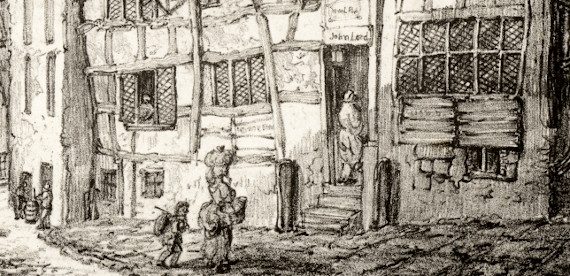

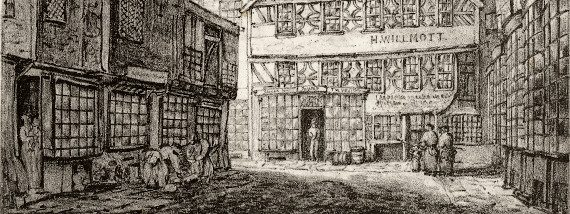

105 : Mr Hyde’s Shop, Market Street

The winner of the most eccentric chimney stack from yesterday’s Market Street view receives a full-frame portrait in this print, Mr Hyde’s Shop. The building seems also to win most picturesque, giving every appearance of being seventeenth-century work with some very elaborate decorative framing. Irish butter, dairy and tea is the stock in trade. The artistic pairing of John Ralston drawing and Agostino Aglio as lithographer continues, but this time Aglio himself prints, and takes a rather cavalier approach to Ralston’s name – his rendering looks more like ‘Rolson’. The publishers, D. & P. Jackson, may not have been delighted to come out as Jakson, but Aglio’s talent in producing an attractive print probably balanced these minor infelicities. As Halloween has already passed, no remarks concerning Dr Jekyll are offered here. Losing a landmark establishment like this must have been one of the less attractive aspects of the Improvement Acts.

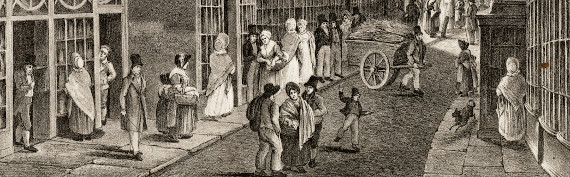

104 : Market Street

We’ve moved a little further up Market Street and up the slope that now has the Arndale on one side of it. From the bend in the street – modernisation straightened as well as widened it – we’re probably looking downhill from about the Spring Gardens level. The shop names are just about visible at full resolution of the scan, with a watchmakers, Clough’s ironmongers, and at the left edge of frame Sharp & Co, with a figure with a barrow just visible in the shade of the entry. Most prominent is Hyde’s Grocery and Tea at no. 88, with a chimney stack that would have given his insurers sleepless nights. It figures in a print of its own tomorrow. Ralston and Aglio again the artist and lithographer, Chater the printer.

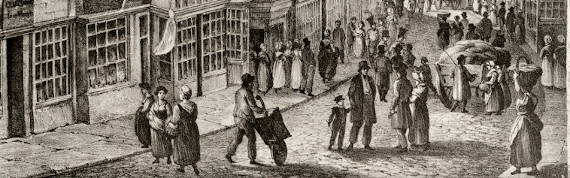

103 : Market Street

We have come a little further up Market Street from yesterday’s view, and have turned about to look back towards the Exchange and Market Place. The rounded end of the Exchange peeps out to orient us – even though it’s long gone, it’s the most familiar feature from an otherwise unrecognisable scene. The publishers, Jackson’s, are the only names present in yesterday’s print in the same series. This view is another Ralston drawing, the lithography by Aglio, and the printer, N. Chater and Co. are a rather less well documented firm than Hullmandel’s. At a casual glance we might again mistake the Manchester of 1823 for York’s Stonegate or Petergate.

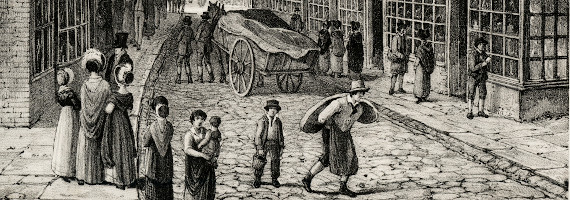

102 : Market Street, Manchester

Today’s image is the first of a series of views of Market Street that dominate the next few days of posts. The modern Mancunian is used to seeing Market Street as a wide thoroughfare, and the narrow nature of the space between buildings here leading away from Market Place demonstrated to the need for the very ‘Improvement’ that the views commemorate. Whether what we have now is a big improvement is perhaps open to discussion; but it’s wider beyond dispute. We met James Duffield Harding yesterday is the lithographer of John Ralston’s original drawing; for this view, he has the only credit, giving the impression he both drew and made the print. The printer, Charles Joseph Hullmandel (1789–1850), was a prominent London printmaker and it’s no surprise to find him responsible for the physical production of this prestige project.

101 : Market Place

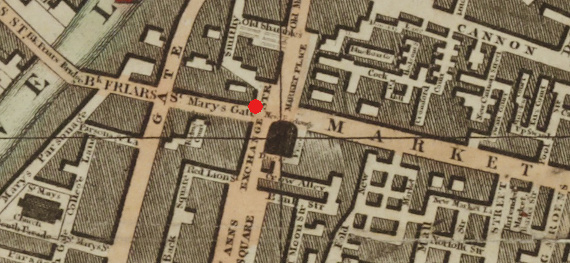

As with yesterday’s view of the Blackfriars Bridge, we’ve already seen a lithograph of Market Place from a very similar angle in the James views series at number 64. This larger print from the ‘Manchester Streets’ series is again a litho from original drawing by John Ralston, this time redrawn on the stone not by Aglio but by the twenty-five-year-old James Duffield Harding (1798-1863), later an influential watercolourist, drawing master and oil painter. Again in keeping with the grander ideas of the series, Harding, like Ralston, Aglio and Mather Brown was not a local boy, but was born and died in the London area. The scene itself is again full of detail, with many more people than James populated his work with; unlike yesterday’s view, however, this scene looking across Market Place and the apsidal end of the Exchange to the right was still visible in May 1823. Ralston’s viewpoint must have been very close to the red dot on this detail from the 1824 Pigot map of Manchester and Salford.

Detail of Market Place and the Exchange from the 1824 Pigot map

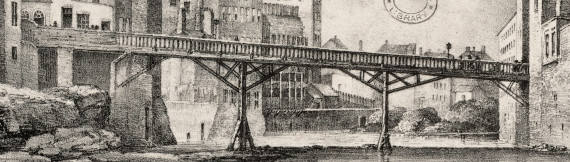

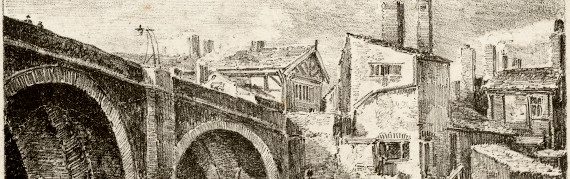

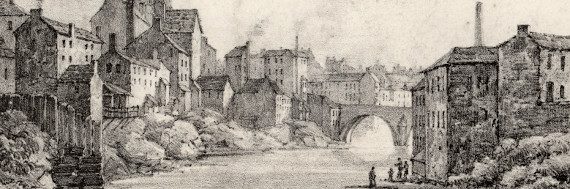

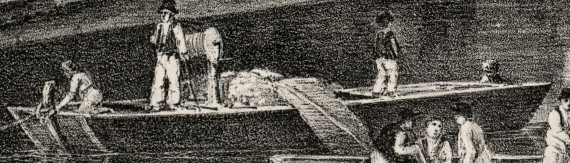

100 : Blackfriars Bridge

We have already looked at a very similar scene to that depicted in this image at numbers 19 and 70. Like the view of King Street in number 99 before the construction of the Town Hall, this view was also a memory by the print date of 1823, the new, stone-built and substantial Blackfriars Bridge having been opened in 1820 (see number 72) to provide the town with a second crossing capable of carrying vehicles. John Ralston is again the original artist, Agostino Aglio the lithographer, and they combine to produce a view from perhaps just a little further back than that by Barritt, and as full of detail as Barritt’s was of watercolour softness. The large lithos are hard to do justice to in a web image. Here is a small detail from the busy and industrious scene on the river to give an impression:

The contrast between the improved and the former, ‘unimproved’ state of the streets and infrastructure is ample to flatter the boroughreeve, constables and commissioners to whom the views were dedicated; the mayor and council who were to replace those officers twenty years later could no doubt look back on what their antecedents had achieved with some pride.

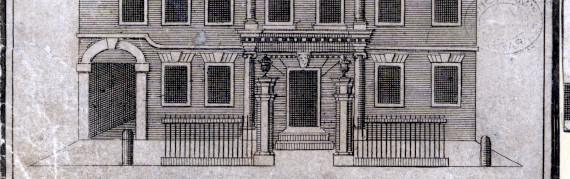

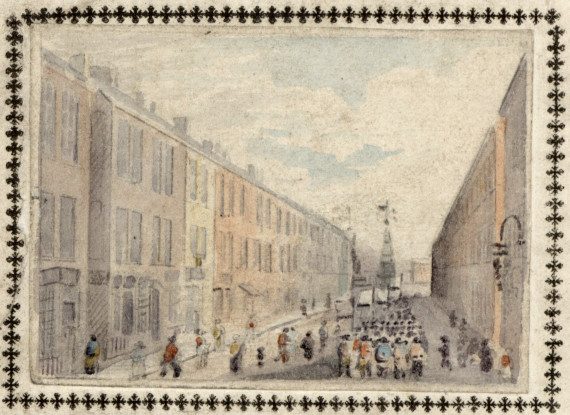

99 : Late Dr White’s House on King Street

After yesterday’s build-up with the cover page to the ‘Manchester Streets’ series, we have this busy scene at the end of a King Street that looks a great deal more like something we might imagine taking place in Bath rather than in Manchester. We’ve seen both the picturesque and the frankly slightly grotty in our views from the Scrapbook to date, but here the highly professional team of John Ralston (1789-1833) drawing and Agostino Aglio (1777-1857) making the lithograph gives us a busy scene, full of life, activity and detail in this 1823 retrospective view. The sheet measures 43×33 cm. in our copy, so there is a luxurious amount of space by comparison with some of the smaller items we’ve seen before. At the right of frame is the beginning of the street sign ‘Red Cross Street’, which was the name of the southern portion of Cross Street; we’re thus looking at where the ‘Old’ – Francis Goodwin’s – Town Hall stood from its beginnings in 1822 until after it was replaced in the ’60s and ’70s by the present gothic town hall on Albert Square. A much smaller and simpler view of this impressive house in the 1740s is above at number 117.

98 : Manchester Streets

With item 98, we turn away from F. Wroe’s contributions to meet up with some significant artists who produced a series of large and fine-quality prints that you may well have seen reproduced more than once in various places, dedicated: ‘To the Boroughreeve, Constables and the Commissioners acting under the Manchester Streets Improvement Act’. Today’s offering is a title-sheet for the series, in which various hands were involved; we’re also in the territory of the ‘Improvement Acts’, a gathering term for a range of parliamentary acts passed across the later eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries to give a variety of local bodies the powers they needed to pave towns and cities, supply them with street lighting, policing, etc. Manchester was the subject of several such acts before 1838, when it was formally incorporated and began to acquire a less ad-hoc machinery of local government. In 1823, when this sheet was printed, the parliamentary representation brought about by the 1832 reform act was still a decade away. The civic pride expressed here, though, goes to significant trouble to show itself anything but provincial. Massachusetts-born Mather Brown (1761-1831) painted the original for this sheet; just in case you hadn’t heard of him, he’s down as the ‘principal Artist to His R.H. the Duke of York’. Celebrated Cremona-born artist (later to do a full-length oil of the young Queen Victoria) Agostino Aglio (1777-1857) was the lithographer of this plate and many of the rest; John Ralston, whose name has been taken in vain rather so far in the Scrapbook with his work indifferently reproduced by others, will show us his paces in the next few plates as painter of the originals. A rather classical un-named allegorical matriarch holds the Gresley arms to represent Manchester tradition (Heraldry later incorporated into the City of Manchester arms), while brushes, easel, and unfurling artwork sit to her left. The whole is published in London, and sold at the ‘Repository of Arts, No 1 Spring Gardens, Manchester’. Ready to be impressed? We’ll see with tomorrow’s number 99.

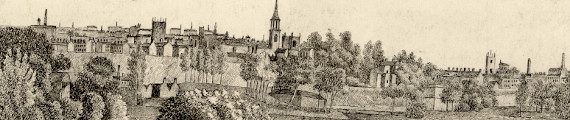

97 : View of Manchester from Strawberry Hill

Today’s image is another F. Wroe redrawing of a print by James Parry (d. 1871). Wroe faithfully reproduces the original text of the print, ‘View of Manchester from Strawberry Hill, on the Bolton Canal, Salford, drawn & engraved by Jas. Parry & pub’d by J. Rogerson, Market Street 1818.’ Despite the signs of burgeoning industry in the shape of factory chimneys, Parry represents Manchester as still dominated by its church spires, St Michael’s on the left, the Collegiate Church, St Anne’s (still with its taller tower), St Mary’s and St. John’s following on. We are even provided with a lady and a gentleman in frock coat for foreground interest, and a labourer on the left who evidently knows his place is in the margin. It’s comforting that Salford is still known around the world for the quality of its wild strawberries.

96 : The Collegiate Church

F. Wroe – probably in the 1880s, judging by his dated work in the Scrapbook – tackling another redrawing of the work of other artists, in this case: ‘The Collegiate Church, Manchester, 1829. Enlarged from a drawing by G. Pickering, Engraved by Edward Finden and published by Mess’ Longman and Co.’ There is a series of rather fine illustrations drawn by Pickering (d. 1857) and engraved by Finden (1791-1857) for the publication of the first series of Traditions of Lancashire by John Roby (1793-1850) (London: Longman, 1829) later in the Scrapbook. Pickering, a Yorkshireman who settled in Liverpool and Birkenhead, provided the art work for other illustrated works on Lancashire and Cheshire. It appears there was no spare copy of the view of the Collegiate Church to include in the Scrapbook, and once again Wroe has obliged. You can see an image of a nicely hand-shaded copy of the original print posted on Tumblr.

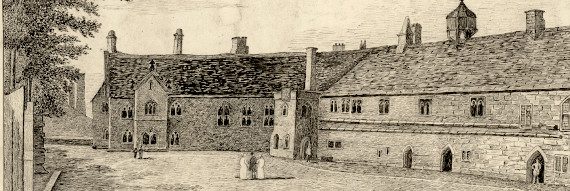

95 : Chetham’s Hospital, Manchester

‘Chetham’s Hospital, Manchester, in 1821, drawn and engraved by James Parry’, ‘Pen and ink by F. Wroe’, to reproduce all the text. Manchester-born James Parry (1795-1871) was, like his father Joseph and several other family members, an artist in oils and an engraver. His self portait and two other oils are at Salford Museum and Art Gallery. We’ll see more by him or based on his work, and that of his father and his elder brother David Henry Parry, later in the scrapbook. Wroe has redrawn the engraving, and after being rather sniffy about his artistic talents, we’d have to admit this rendering is better. We have a copy of the print on which this is based, and did a short blog post about it a while ago.

James Parry’s original 1821 print