The Cross Dressing Chevalier d’Eon

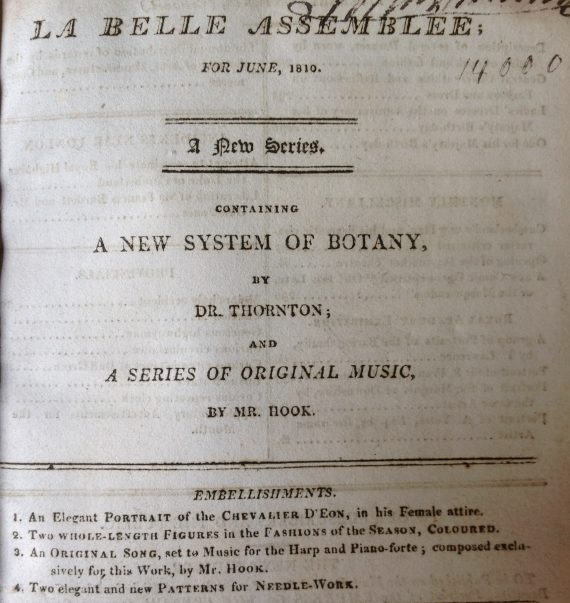

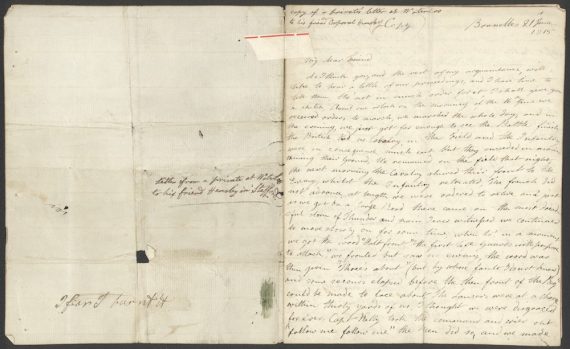

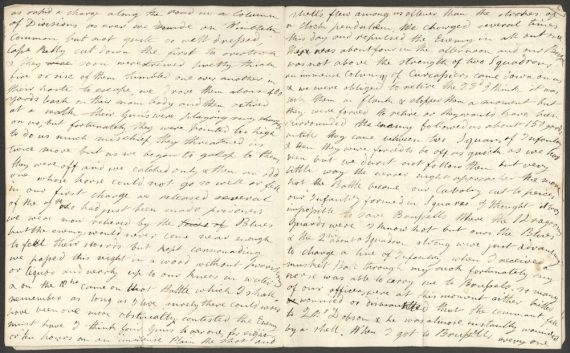

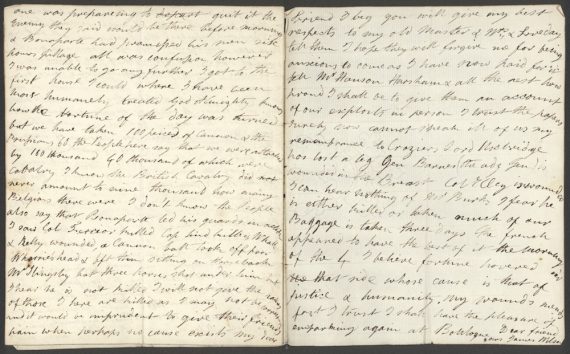

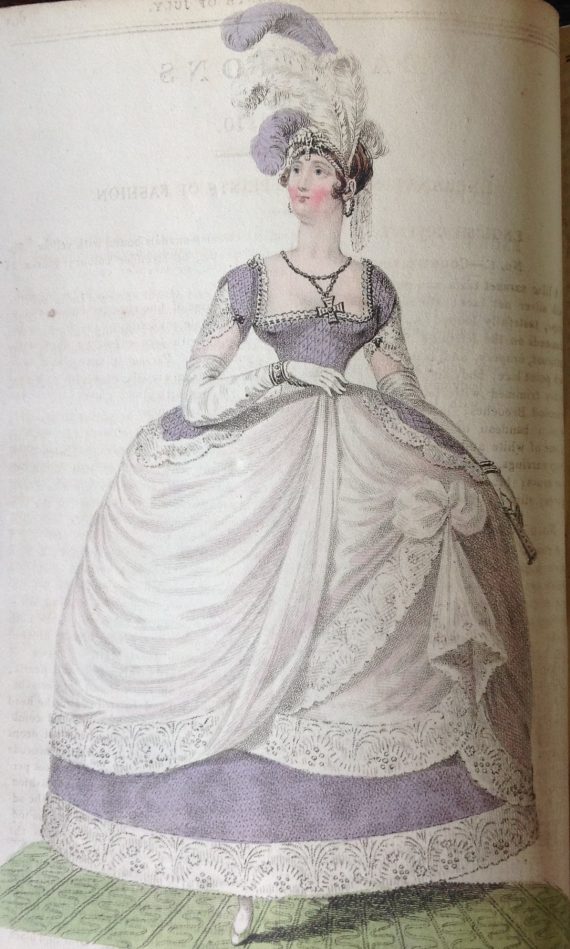

Leave a CommentThe first article in the June 1810 copy of the ladies’ magazine La Belle Assemblée is described as being one in a series of biographical sketches and is entitled ‘Memoirs of the Chevalier d’Eon’. The accompanying engraved portrait features what appears to be a man wearing a woman’s dress and head-dress but with a military medal pinned to his shoulder. The article begins ‘The following life of the Chevalier d’Eon has been compiled with much care from a document which we believe to have been by his own hand. The facts will speak for themselves’.

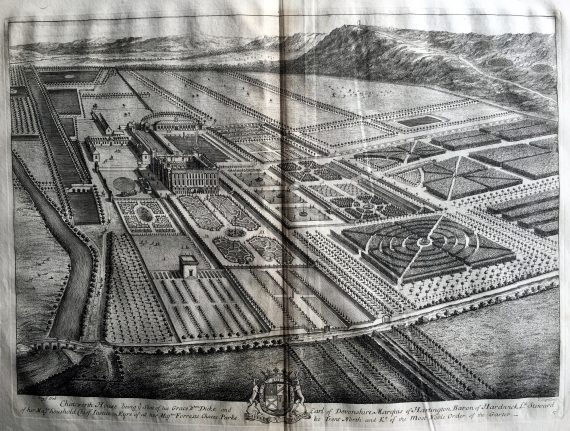

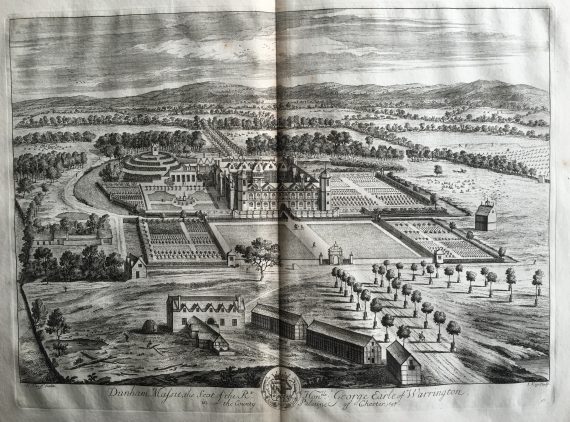

La Belle Assemblée, or Bell’s Court and Fashionable Magazine Addressed Particularly to the Ladies, was a monthly periodical which first appeared in February 1806 and continued (under that particular title) until 1832. It was published in two sections, with the first typically including a biographical sketch, a summary of current politics, a section for provincial news, reviews of paintings, books, music and the theatre, short stories and serialisations and a final section of notable births, marriages and deaths.

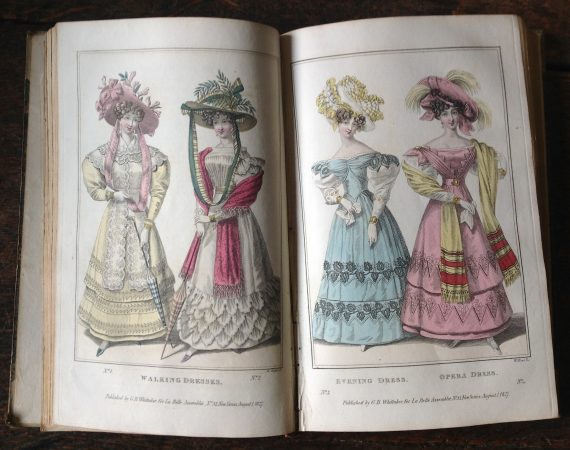

The second part of the magazine was devoted to fashion. It recorded the dress worn by the social elite at important events, and also included coloured fashion plates, with detailed descriptions, which were designed to enable ladies of fashion to have their local dressmakers copy them.

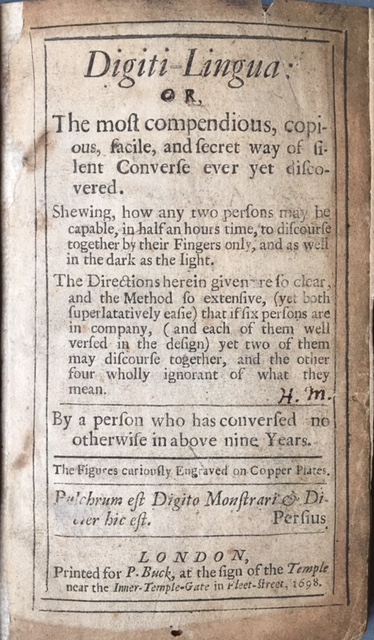

The library has two bound volumes which include copies of La Belle Assemblee. The later volume contains editions of the magazine published from July to December 1827, but the earlier one is bound with three unrelated French publications (possibly on the grounds that it has a French title!)

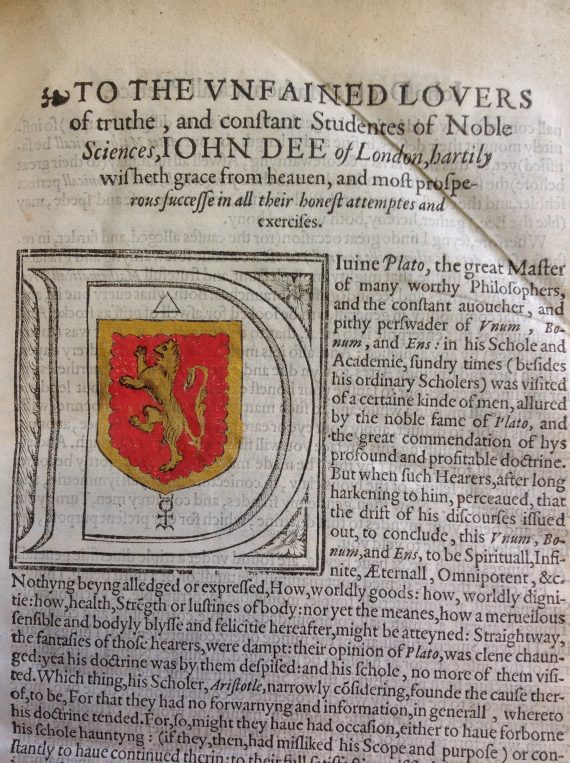

The story of Charles Geneviève Louis Auguste André Timothée d’Eon de Beaumont, diplomat, soldier, spy, and cross-dresser, provoked much interest during his own lifetime, with wagers being made as to his true sex, and his life has remained a subject of fascination ever since.

D’Eon was from an old and noble family, and was a highly intelligent man and qualified lawyer who also became a prolific author. He became involved with the court and diplomatic service of Louis XV, operating as a spy and frequently in disguise. He later claimed that in 1755 he had attended a ball at Versailles dressed as a woman where, in the words of the DNB, ‘after briefly revealing his masculinity, [he] seduced Madame de Pompadour’.

Between 1760 and 1762 he joined the French army and had a brief but dazzling military career against the Prussians. He then played a key role in negotiating the Peace of Paris in 1763, ending the seven years war between France and Britain, and was awarded the Order of St Louis, becoming a ‘chevalier’.

By 1763 the Chevalier was effectively working in London as a spy for Louis XV and living on a lavish scale, entertaining such important names as Horace Walpole and David Hume, and spending his money on rare books and manuscripts, fine clothes, and corsets.

However, he quarrelled with his superiors, tried to blackmail the French government by threatening to reveal official secrets and lost his French pension as a result. He remained deeply loyal to the king himself, from whom he received a secret pension until Louis died in May 1774. Eventually an agreement was reached that D’Eon could return to France if he handed over all his papers and also agreed to dress and live as a woman (apparently Marie Antoinette’s dressmaker was to provide his clothes). It is suggested that this was an attempt by the French government to control and disempower D’Eon, who refused and was actually imprisoned for appearing publicly in his military uniform.

Finally, in 1785, the Chevalier returned to England, where he owed a great deal of money and became embroiled in legal disputes. Although he was by now in his sixties, to generate some income, he ended up giving fencing displays, dressed as a woman, and in partnership with Mrs Bateman, an actress and female fencer. Despite this he was briefly imprisoned for bankruptcy in 1804. During this period he was lodging in Milman Street in London with a Mrs Mary Cole with whom he lived, as a woman, for 14 years. He died there in May 1810 and a post mortem examination confirmed that ‘his male organs were perfectly formed’. This came as a great shock to Mrs Cole, who was apparently unaware of his birth gender.

He was buried in St Pancras Old Churchyard (sadly the grave no longer exists) and, as he had failed to sign the will which he had drawn up, his papers and his belongings were sold by Christies in 1813.

There have been a number of biographies of the Chevalier since his death, and much debate as to the extent to which he embraced the female role and whether he was a man who enjoyed occasional cross dressing, but was forced to permanently adopt a female identity against his will, or whether he might have described himself today as transgender.

The NPG copy is by a theatrical painter called Thomas Stewart, and, as Philip Mould the London dealer who discovered it says, ‘What is so unusual about this portrait is that it is so brazenly demonstrative, in a period when you don’t normally get that type of alternative persona expressed in portraiture…There is no attempt to soften his physiognomy – basically, he was a bloke in a dress with a hat’

The fascinating thing about the article in La Belle Assemblee is that it was published in an English ladies’ magazine within weeks of the Chevalier’s death and is both factual, respectful and sympathetic, with no hint of scandal or lasciviousness.

Note: from the guide to the Beaumont Society, a support group for the transgender community, which took its name from the Chevalier d’Eon de Beaumont:

“Cross-dressing means different things to different people and tends to be little understood, though work in recent years to change public attitudes means that it is, perhaps, no longer a subject of fear but seen as being a means of expression. It is a subject commonly treated in the press in a way that exploits for sensationalism, although women’s magazines do seem to be more understanding. Perhaps it is not seen as a threat to women as it is to men.”